It would be an exaggeration to talk about “the literature of the Pogrom” as there simply isn’t very much of it. Instead, this post looks at various works in which the Pogrom figures to differing degrees – a novel, two plays, a poem and two contemporary pamphlets of political analysis:

- Michael McLaverty, Call My Brother Back

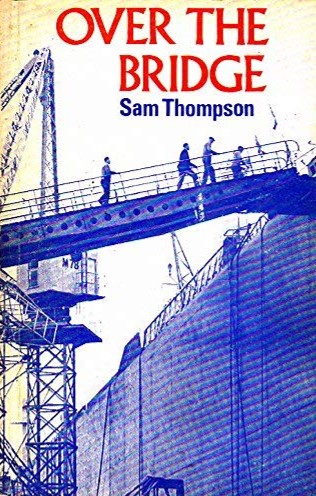

- Sam Thompson, The Long Dark Street

- Sam Thompson, Over the Bridge

- Paul Muldoon, The Belfast Pogrom: Some Observations

- G.B. Kenna, Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922

- H.A. Campbell, From Capitalism to Cannibalism – An Account of the Belfast Capitalist Pogrom

This does not purport to be an exhaustive list of all non-historical writing about the Pogrom so I would be glad to hear of other similar works.

Estimated reading time: 40 minutes

Call My Brother Back

Michael McLaverty

Michael McLaverty was born in Monaghan in 1904. While working as a school-teacher in west Belfast in the 1930s, he began writing short stories and developed a reputation as “one of the foremost proponents of the Irish short story, [who] left an indelible mark on the literary landscape.”1

Call My Brother Back, published in 1939, was the first time he turned to the novel as a literary form.

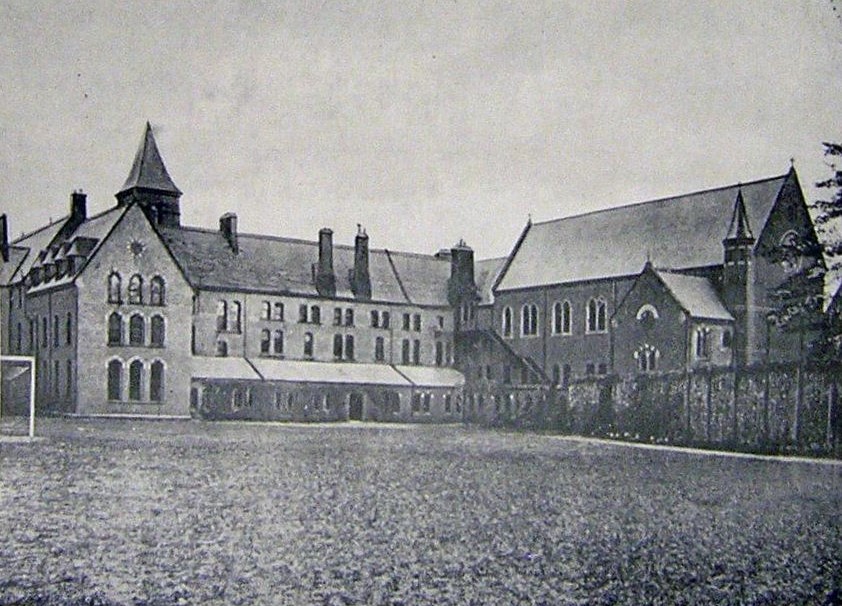

The book begins with a young boy, Colm McNeill, growing up on Rathlin Island with his parents and younger siblings Jamesy and Clare; his older brother Alec and older sister Theresa live in Belfast. After the death of his father, he is sent on a scholarship – paid for by a kindly parish priest – as a boarder to “St Kevin’s College” in Belfast, a barely-disguised stand-in for St Malachy’s on the Antrim Road. Although the novel is not autobiographical, McLaverty draws on his own experiences here – as a child, his family had moved to Rathlin, then to Belfast, where he attended St Malachy’s.

St Malachy’s College

Just before the Easter holidays, Colm receives a letter from his mother with the welcome news that the rest of the family are moving to Belfast. Alec buys second-hand furniture from the market in Smithfield and they bring it to the family’s new home – although not made explicit, this is located in Beechmount, where the McLavertys had lived: “At the top of the street were the brickyard and brickfields, and beyond that again, more fields straggling up to the foot of a mountain,” a clear reference to the Clowney Brickworks, which was at the end of the street of the same name.2

Naturally Colm is delighted, as it means he no longer has to attend school as a boarder but can now stay with his family. He and Jamesy soon make friends with the neighbouring boys and join their football team, Brickfield Star:

“The following Saturday they challenged a Protestant team to a match in the Bog Meadows … when Jamesy sent in a shot that just passed over the goalkeeper’s head, a dispute arose. Brickfield Star said it was a good goal but the other team maintained that the ball went over the ‘bar.’ The match finished in a fight.”3

The opposing team sing Dolly’s Brae, Brickfield Star sing the Soldier’s Song, thrown stones are exchanged and, honour satisfied, both teams go home.

After a spell in hospital with an ear infection, Colm comes home to find two new pictures hanging on the kitchen wall, “one of P.H. Pearse and a group of men signing the Republican Declaration of 1916, and another of Thomas MacDonagh.” It is a subtle portent of things to come.4

Colm goes into town on the Twelfth for the Orange parade – for him, it is a spectacle to be watched and even enjoyed, even though he is clearly old enough to understand the political connotations of what he sees; perhaps, he even prefers to pretend those connotations are not present and instead, to concentrate on simply being entertained:

“Glossy painted banners, some of biblical subjects, led each section, followed by a band. There were bands of all kinds: flute bands, brass bands, pipers’ bands, accordion bands, all playing at once, and here and there men in their shirt-sleeves hammering the big drums. The air was alive with sound; the notes from the miscellany of instruments whirled in the air, interlaced, shrieked and descended to be sent sky-high again by the stone-crushing noise from the big drums.”5

But this marks the beginning of the end of his youthful naivety:

“That day passed in peace, but the fire of the leaders’ speeches smouldered for days in the minds of the common people, and towards the end of the month a mob of them, armed with sticks, invaded the shipyards and chased out the Catholic workers. Then riots began in the poorer parts of the city. Snipers hid on the roofs of houses and factories and swept the streets with bullets. The military were called out, and the lovely summer evenings were perforated by the rattle of rifles and machine guns.”6

By the end of the summer, when Colm returns to school, “… Alec had joined the Irish Republican Army. He sold the pigeons, for he had no time for them and no heart to work with them.”7

The tension of life in Belfast gradually becomes suffocating: “The armoured car rattled up the street and throbbed in the kitchen. Their eyes were alert and steady with fear as it passed the house; and then with suppressed delight as they heard its noise fade in the distance.”8

Even praying the rosary offers no reprieve: “Once Rover barked when they were at their prayers and Colm turned out the light and patted the dog’s head. Then they knelt in silence, waiting any moment for the back-door to be battered or shots fired into the kitchen.”9

The family home is raided one night by military and police searching for Alec, guns, or both, but he has gone on the run and, to avoid arrest, is now sleeping at the house of Theresa’s mother-in-law, Mrs Heaney. His framed pictures are smashed by a policeman with a southern brogue. When he returns home the following morning for breakfast, he explains to them he was lucky: “’I met the postman and he was telling me that six were arrested in the Kashmir Road.’”10

One morning, Colm oversleeps, so Alec gives him money for the tram to get to school:

“The tram-conductor was very excited and at every stop he shouted ‘We mightn’t get down the road at all. There’s sniping going on, all the morning.’ … Nearing Conway Street shots rang out and Colm and the other passengers lay flat on the corrugated floor. There was a crack like a stone through ice and when the tram stopped in the shelter of a mill a man stood up beside Colm with blood claw-streaming from a wound in his hand. ‘I’m hit!’ he said.’”11

Passengers cower on a Belfast tram (Illustrated London News, 1 April 1922)

Alighting from the tram, he is forced to take refuge in a stranger’s house, the only one with its door half-open, as snipers are exchanging shots, clearing the streets: “A shadow passed the window and he saw an armoured car. He shut his eyes and crouched low as he heard the dic-a-dic-a-dic-a-dic-a from the Hotchkiss gun.”12

The school is raided by military and Colm is sent outside the gates with the other day-students, while the boarders are gathered together in a hall. Afterwards, one of the boarders gives the others a breathless account of the raid: “‘Father Black sat at the rostrum and he paid as much heed to the raiders as he would to the window-cleaners … They searched Father Black’s room because he wouldn’t notice them in the Study Hall and they confiscated an old air gun that he had for pelting cats off the wall.’”13

Here, once more, McLaverty is borrowing from real life, as St Malachy’s was in fact raided three times in the space of a fortnight in April 1921 – one of these raids led to a court-martial appearance for one of the priests: “Rev. J. McGaughan, St. Malachy’s College, Belfast, [was] charged at Belfast, that the on the 9th inst., when St. Malachy’s College was searched a miniature rifle was found under the staircase. He was fined £5 or, in default, one month’s imprisonment, the rifle to be forfeited.”14

Schoolboys from St Malachy’s watch a British Army sentry during a military raid on the college

Other historical events also appear in the book. In a clear reference to the June 1921 killing of three men, Alexander McBride, Malachy Halfpenny and William Kerr, by a police “murder gang,” Alec comes home from Mass one morning to tell the others: “’I was up seeing a poor fellow that was dragged from his bed last night and murdered. He’s lying at the side of a lonin away beyond the brickfields.’” The body of Kerr was found in a laneway off the Springfield Road.15

Snatching a brief respite from the violence, Colm and his two brothers set out to climb Black Mountain. Once there, they look down on the city, spotting and naming the various churches – including, in another reference to Beechmount: “Near their own street was the Dominican Convent, its fields very green and its hockey posts very white.”16

Colm’s older brother even manages to step out of his IRA role for a moment: “’Wouldn’t you think now to see all the churches,’ smiled Alec, ‘and all the factories and playgrounds, that it was a Christian town?’ and he lay back in the heather, flung his arms wide and laughed.”17

In the autumn, the scale of the violence dies down and Colm and Clare venture into Smithfield market where he buys her a goldfish. Alec has resumed sleeping at home, as raids are much less frequent than previously; ominously, at bedtime, he remarks: “’It’s a long time since I remember so still a night.’”18

That night, their panicking mother wakes them – a group of men are outside the house. Alec assumes the police have come to arrest him and goes to answer the door as Colm lies listening in bed: “And then the door opened. There was a stumble. Shots cracked and split the air. The mother screamed and ran downstairs. In the hallway Alec lay. His shirt was wet with blood. She lifted his head and clasped it in her two hands: ‘The priest! The priest!’”19

Colm sprints barefoot to the convent, on the way passing the body of the family dog which has also been shot; returning to the house by a short-cut, one of the priests carries him across the cinders of the brickfield – a possible reference to the legend of St Christopher – but by the time they arrive, Alec is already dead. At the funeral, the police snatch a tricolour from Alec’s coffin, but: “That night Alec’s comrades stole into the graveyard and fired three volleys over his grave.”20

With Alec gone and the family’s income wiped out apart from Jamesy’s meagre wages as a messenger-boy, Colm has to drop out of school to work as a clerk in a bakery, while their mother gets part-time work cleaning the parish church. But Mrs Heaney brings welcome news by advising them that they can apply to the American White Cross Fund for relief; soon, the Fund is giving them a guinea a week on top of the boys’ wages.

On Christmas Eve, Colm and Jamesy set out for confession in St Paul’s on the Falls Road but it is too full; so is St Peter’s, so they decide to go into St Mary’s in the city centre. They mingle with the crowds of shoppers, observe the street-traders, hucksters and conmen at work, a Salvation Army group singing carols and a street preacher telling how he was saved.

Near North St, a man in a tram-conductor’s uniform climbs onto a wooden box and begins a speech, appealing for peace:

“’Who does the riotin’ and the fightin’? Look at the list of the dead and wounded these days in the papers? What d’ye see? They are all the names of workers – all workin’ people! Ye never seen shooting in the Malone Road or Balmoral or in the other flashy districts of this town.’”21

In one of the most-quoted passages of the book, the man exclaims:

“‘Yez are all mugs in this town! All mugs! Listen to this brothers! Supposin’ ye got all the Orange sashes and all the Green sashes in this town and ye tied them around loaves of bread and flung them over Queen’s Bridge, what would happen? … What would happen? … The gulls – the gulls that fly in the air, what would they do, they’d go for the bread! But you – the other gulls – would go for the sashes every time!’”22

The novel closes with Colm going to sleep that night, his mind gently wandering; the very last phrase in the book is a direct echo from the street-orator’s speech earlier, “… a rickle of bones falling dead in York Street…”23

The Long Back Street

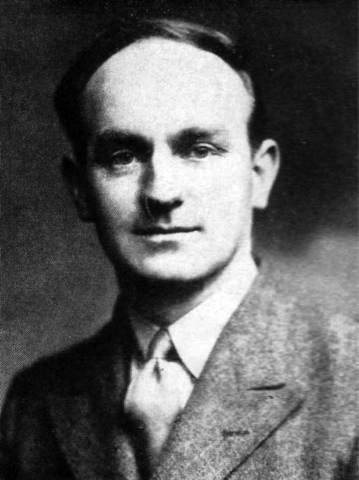

Childhood and the loss of innocence are also central themes in The Long Back Street, an autobiographical radio play written by Sam Thompson and broadcast on the BBC Northern Ireland Home Service on 6 May 1959. Born in 1916 in Montrose St in east Belfast, Thompson went to work as an apprentice painter in the shipyard in 1930, when he was aged just 14; his four older brothers already worked there.

As a child, he had seen a Catholic delivery man dragged from his cart, beaten senseless and left for dead by a sectarian mob within a hundred yards of his home; the memory stayed with him for life.24

Connal Parr has noted that, “Sam Thompson makes the crossover between politics and the arts particularly explicit because he both wrote plays and stood for election” – he ran as an unsuccessful candidate for the Northern Ireland Labour Party in South Down in 1964.25

Sam Thompson

The Pogrom looms large as the play opens, with children sitting round a kitchen fire:

“NARRATOR: It was a nice warm fire. But down our long back street there were ugly and savage fires.

FATHER: That spirit and grocer’s shop at the corner of the next street is gone – gutted and burnt out.

NARRATOR: It was the year 1922. I was six years old at the time. Our long back street began at the Albertbridge Road end where our family lived at No. 2 … I was forbidden by my parents to play at the other end of the street which could lead me on to the Newtownards Road and into what they called ‘the trouble area.’”26

“That spirit and grocer’s shop at the corner of the next street is gone – gutted and burnt out.” A looted and burned spirit grocers on Beersbridge Road, east Belfast (Illustrated London News, 4 September 1920)

The play depicts a typical childhood in Protestant working-class east Belfast: going to football matches of the local team, Glentoran, attending Sunday school and joining a Christmas Club: “…we put away a copper or two every week in the wee shop around our corner.”27

Saving for Christmas in this manner is not limited to children: “A fowl for the Christmas dinner was the ambition of every family on our street.”28

Nor is Christmas necessarily a time of abundance – one boy is mocked by his friends for receiving a bicycle, handed down from an older sibling who got it as a present the previous Christmas; the boy’s father has touched up the paintwork in a vain effort to make it look new. Such poverty is ever-present: the children have to bring in a penny each week for the school’s coal and gas fund but not all of them have it – the suggestion is that their fathers are spending it on “Red Biddy” (whiskey) instead.

Later in the play, by now aged 9, he describes his first encounter with Catholics as he and his friends play football in the local Victoria Park – it is an interesting reversal of McLaverty’s football scene, as this one does not end with the boys throwing stones at each other:

“NARRATOR: …it was the first time we had met up with other boys whom we knew for sure were Catholics. And there was no mistaking the tension that existed between us, until all of us realized [sic] that neither of us had horns or had pitch forks dangling out of our pockets.”29

In this, a rejection of sectarianism can be seen as the boys try to cling on to more simple pursuits. Nonetheless, unionist culture is an important part of community life: in the run-up to the Twelfth, he and his friends collect tree branches for the local bonfire, the kerbstones are re-painted red, white and blue and a street artist touches up a nearby mural of a “faded and neglected King Billy.”30

At one point, it appears that the events of the Pogrom are about to be re-lived:

“NARRATOR: One day coming home from the Victoria Park, we saw a different kind of procession. It was a mob of men in dungarees and from a distance it revived memories of another kind of mob we had once known.

1ST BOY: Maybe they’re after a taig, eh.

NARRATOR: When we did catch up with the mob of marching men, we discovered that they weren’t carrying sticks to beat or kick people. They were carrying scripture bannerets to save people.”31

Near the end of the play, the by-now teenaged Thompson encounters an election meeting being held on the street – the adult Thompson uses this scene to appeal for working-class solidarity in preference to the sectarianism in which the teenager has grown up:

“SPEAKER: A united unionism is our bulwark against popery. Let us never forget 1690 and the glorious siege of Derry. Let our watchword be ‘No Surrender’ and ‘Not an inch’ …

1st MAN: I’m here to ask you what you intend to do for the unemployed in this district. The shipyard’s slack and they’re paying off in the mills.”32

The crowd turn angrily on this man but he remains adamant: “I’m neither a taig nor a Bolshevist. I hold labour views and I expect sensible answers to my questions … You can’t ate Derry’s Walls when you’re hungry.”33

Over the Bridge

Thompson explored similar themes more closely in his most famous play, Over the Bridge. This was his first stage play, but proved hugely controversial.

Offended by the play’s potential to highlight “religious and political controversies,” the board of directors of the Group Theatre demanded changes to the script. When Thompson refused, “…the Group’s directors elected by six votes to two to withdraw it just a fortnight before its opening night in May 1959.”34

As a protest against the board’s decision, director James Ellis and several of the actors resigned from the Group Theatre. “With Ellis and a few of the Group’s actors, Thompson founded the new company ‘Bridge Productions Ltd’ and finally staged the play at the end of January 1960 where it was seen by an estimated 46,000 people at the Empire Theatre over the course of six weeks.”35

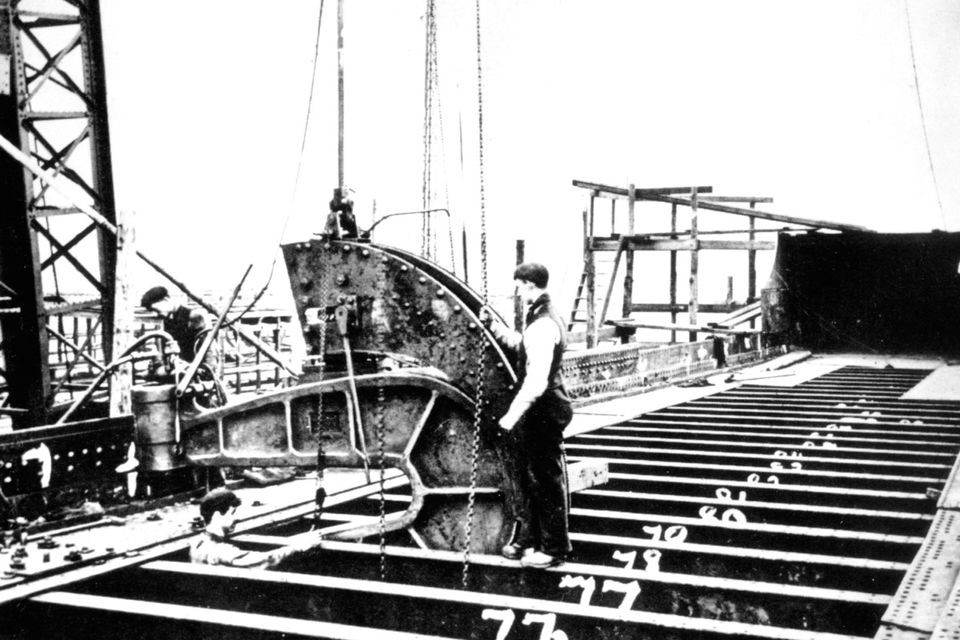

Shipyard workers knocking off work at Harland & Wolff

The play revolves around a group of trade union members in the shipyard. The main character is Davy Mitchell, a senior shop steward, now nearing 70 years of age. Illustrating the close-knit nature of employment in the shipyard, the others are also in his inner circle outside work: Rabbie White is his friend, union colleague and next-door neighbour; Warren Baxter is engaged to be married to Davy’s daughter; George Mitchell is Davy’s brother.

Although the play is set at an indeterminate time after the Pogrom, much of what unfolds could just as easily be set in July 1920, as the events of that month are burned into the men’s memories.

At an early point, Rabbie expresses Thompson’s core theme: “Davy Mitchell knows from bitter experience that sectarian trouble inside the union needs to be nipped in the bud for the sake of everybody.”36

However, such tensions are simmering in the background. An apprentice comes in to fill the men’s tea cans for break time:

“EPHRAIM: He sacked me as his can boy because I fill Peter O’Boyle’s.

RABBIE: That doesn’t make any sense to me, sonny.

EPHRAIM: It does to Archie Kerr. He told me that no Prod apprentice should fill a fenian’s can. Archie gave his can to another apprentice who’s in a Junior Orange Lodge and who only fills Prod cans.”37

Some of the men gather in advance of a union meeting and Archie Kerr gives vent to his feelings:

“RABBIE: Did you see any sign of Peter O’Boyle on your way down?

ARCHIE: [viciously]: That Fenian gat …

BAXTER: We’ll not make much progress at the meeting if that’s going to be your attitude.

ARCHIE: I know where I stand, Baxter, which is more than you can say.

BAXTER: Meaning what?

ARCHIE: You’re not even a member of the Orange Order nor any loyalist organization, for that matter … It’s half-baked Prods like you that has us where we are today – fighting with our backs to the wall against the advancing scum of Popery …. For years we fought against the infiltration of Communism, and by heavens we’ll take our stand against Popeheads holding office on the district committee.”38

When Davy and Peter O’Boyle join the others, Davy reminds them of where such attitudes took them before:

“DAVY: You know what happened in the twenties when this sort of talk got out of hand. It was nearly the means of splitting our union …

PETER: I have been the victim of a whispering campaign … and I accuse that man sitting there of being the instigator of it.

ARCHIE: You’re a fenian liar …

PETER: That man has scandalised me around the shipyard as a Republican and a member of an illegal organisation.”39

Rivetters at work in Harland & Wolff

That night, there is a mysterious explosion at an electricity sub-station further out in the harbour – the rumour-mill swiftly attributes responsibility to the IRA and this has immediate repercussions for Catholics working in the shipyard:

“BAXTER: When we were lined up at the time-office tonight waiting to throw in our boards, word came through that trouble had broken out at the deep water wharf. A mob cleared out every Catholic on the two boats down there, and one man who didn’t get away quick enough got his mouth split.”40

Surprisingly, given their recent altercation, Archie advises Peter to stay away from work the next morning. However, it is unclear whether this is a threat on his part, or if he is offering the advice for Peter’s own good.

Here, it is impossible not to see parallels with the outbreak of the Pogrom in 1920 as, egged on by Carson’s speech on the Twelfth – “we will tolerate no Sinn Fein” – Catholics and so-called “rotten Prods” were violently expelled from the shipyards. Rabbie reinforces this point, as it now seems history is about to be repeated:

“RABBIE: In the early twenties, Warren, they chased the Catholics out of the shipyard and Jimmy Nugent was one of the ones who was too slow getting off his mark. When the mob caught up with him they threw him from the boat deck of the boat he was working on into the tide. That cratur had to swim fully clothed for fifty yards to get to the other side of the channel. But that wasn’t the end of it, Warren. When he did get to the other side they had a reception party all lined up for him, and they made him a target for bolts, stones and rivets. He was a sorry sight when they had finished with him.”41

Next morning, Fox, the foreman, is short thirty men from his department – none of the Catholics except Peter have turned up for work. Archie comes in, worried, as he has heard rumours of action being planned against Peter – Rabbie warns Fox, “…there’s a mob of men heading for this shop to ferret O’Boyle out.”42

When the mob arrives, Fox tries to reason with them, but to no avail, so he decides to phone the police – however, the mob have cut the phone lines. Davy then goes out to them and comes back with a message that if Peter leaves the yard at lunchtime, he won’t be harmed. However, Peter is adamant that he is staying at work and shouts from a window at the mob: “Nobody’s goin’ to chase me out of my job … Do you hear that, you bastards, nobody puts me out of my job!”43

Fox and the union men, apart from Davy, file out of the workshop while the mob leader and two of his henchmen come in:

“LEADER: What are your intentions?

PETER: Why not wait til ten past one and find out.

LEADER: Don’t try to be awkward, friend. If you’re still here at ten past one, that crowd will smash your skull like a vice.

PETER: What have you got against me? I don’t even know you.

LEADER: I know you are a Popehead and a defiant bastard … When there’s an ultimatum sent out that Popeheads are not to come in to work, there’s no exceptions. [He pauses.] You’re a Popehead.”44

The other union men return and beg Peter to go but he refuses to change his mind; the others, knowing that violence is now inevitable, make to leave – but Davy remains:

“RABBIE: If you’re not going with us, ould hand, just where exactly do you think you’re going?

DAVY: To my bench out there when the horn blows – to start work.

BAXTER: But you can’t do that Davy, they’ll tear you apart.

DAVY: Peter’s my mate at that bench. If he lifts a tool to start work, I’m duty bound as a trade unionist to work with him.

RABBIE: What are you trying to prove, Davy? If Peter or you lift one tool at that bench, it’ll be your last …

DAVY: All my life I’ve fought for the principles of my union and Peter here fought for them too. Would you want me to refuse to work with him, because he upholds what is his right, to work without intimidation? … If I refuse to go out there and stand alongside my mate at that bench, everything I have ever fought for or believed in has been nothing.”45

It doesn’t end well for Davy or Peter.

The Belfast Pogrom: Some Observations

The most recent work about the Pogrom is a poem written by Paul Muldoon. This was commissioned by UCD Library in 2023 as part of “Poetry as Commemoration,” an initiative of the Decade of Centenaries programme of the Irish government’s Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media.

Once again, the shipyards are referenced, but here, Muldoon contrasts loyalist working-class east Belfast with nationalist working-class west Belfast:

The shipyard workers are no lighter on their feet

than the linen workers who flock

to Ross’s Mill on Odessa Street

to wrangle a bed sheet

out of sullen flax.

The shipyard workers are no lighter on their feet

than this newly launched ship of the fleet

laying about it with its fluke.

The linen workers on Odessa Street

look to his nosebag for the mummy wheat

that may raise a horse-king from his cart-catafalque.

The shipyard workers are no lighter on their feet

than when they greet

the Catholics among them with a wrist-flick

of nuts and bolts. In Ross’s Mill on Odessa Street

the tradition of drinking whiskey neat

extends to the recent influx

of shipyard workers never lighter on their feet

than when they’re driven back by the heat

from a house they’ve torched. The black snowflakes

that settle on the linen workers of Odessa Street

summon quite bittersweet

memories of a Catholic boy recently flogged

by the shipyard workers no lighter on their feet

than the parakeet

on his shoulder. The boy’s back striped like the flag

flying over Ross’s Mill on Odessa Street.

When it comes to beating a retreat

through a mass of blood and brain-flecks

the shipyard workers are no lighter on their feet than the linen workers of Odessa Street.46

Mural commemorating the women who worked in Ross’s Mill (© Belfast Women’s History Tour)

Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922

(This section of the post is based on an article I wrote for History Ireland magazine in 2020)47

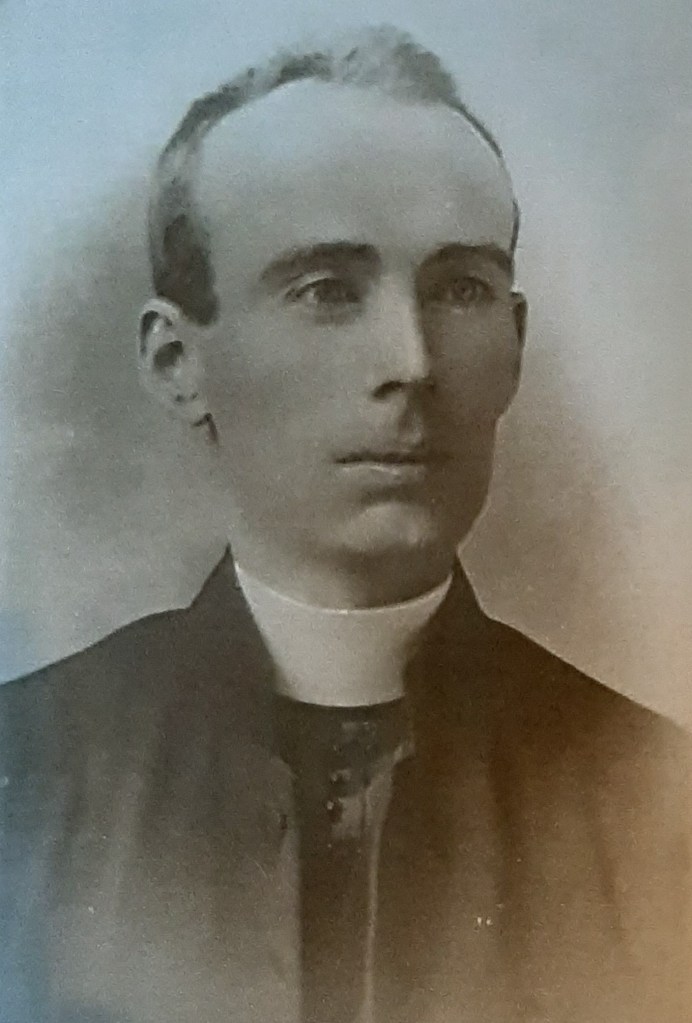

Fr John Hassan

In the summer of 1922, someone who was not the originally-intended author wrote a pamphlet under a pseudonym; it was published by a company that may not have actually existed and all but 18 copies were pulped before they left the printer. Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922 was intended to “…deal with the mountain of lies by which the entire world had been duped and the poor Catholics of Belfast choked.”48

Michael Collins, taking a more active interest in the north since becoming chairman of the Provisional Government, sent fellow-Corkman Patrick O’Driscoll to investigate. O’Driscoll told University College Cork registrar Alfred O’Rahilly that: “…the bishop of Down and Connor, the priests and others gave me numerous instances of how the three Belfast Orange papers had by suppressio veri and suggestio falsi misled the world as to the situation there.”49

O’Driscoll persuaded O’Rahilly that: “From all the facts that could be gleaned a genius could write one of the most powerful indictments of Orangeism ever published.”50

O’Rahilly met Collins in mid-April 1922 and agreed to take on the project. At Collins’ request, the Bishop of Down and Connor, Joseph MacRory, assigned the curate of St Mary’s parish in Belfast city centre, Fr John Hassan, to help compile information for O’Rahilly. Collins had encountered Hassan earlier that month when he was one of a combined delegation of northern churchmen, IRA officers and Sinn Féin leaders who met the Provisional Government to explain the gravity of the situation to them.51

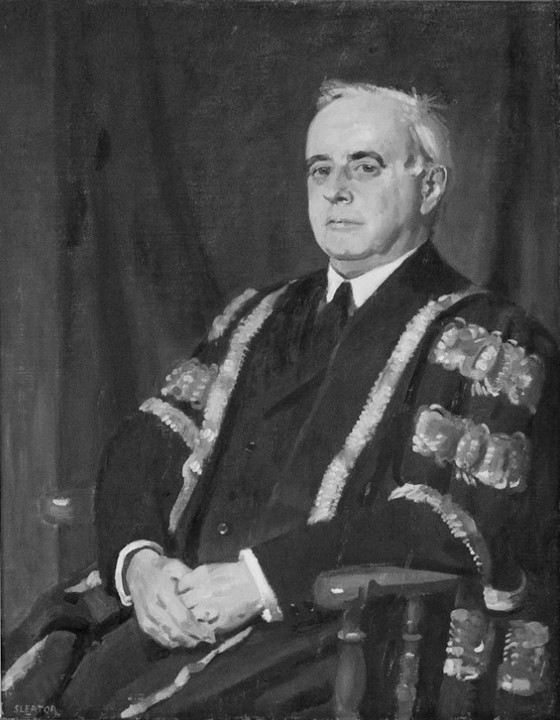

Alfred O’Rahilly

A first draft was completed in early May but O’Rahilly was then abroad for the rest of that month. Hassan continued his research, while growing anxious at not having heard from O’Rahilly. Eventually, Collins agreed to fund publication of Hassan’s work under the pseudonym G.B. Kenna – the intention was that this would be an interim report, with O’Rahilly’s more comprehensive work to be published later. “O’Connell Publishing Company, Dublin” was the official publisher although its very existence remains doubtful.

Hassan’s foreword to the pamphlet was dated 1 August but by then, the Civil War in the south was five weeks old and Collins’ Provisional Government had more pressing concerns than the fate of Belfast Catholics. The same day, it established a North East Policy Committee to review the government’s position on the north.

Among its members was Ernest Blythe, a republican from an Antrim Church of Ireland background. At one time Centre of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Belfast, later an organiser for the Irish Volunteers in Clare, he was elected to the First Dáil as TD for Monaghan North. He had opposed the Dáil declaration of a “Belfast boycott” in August 1920 as a response to the initial outbreak of the Pogrom, saying: “To declare an economic blockade of Belfast would be the worst possible step to take. If it were taken it would destroy for ever the possibility of any union.”52

Ernest Blythe (©

National Library of Ireland)

On 9 August 1922, Blythe wrote to his fellow committee members – his assessment was coloured by the outbreak of the Civil War: “Heretofore our Northern policy has been really, though not ostensibly, dictated by Irregulars. In scrapping their North Eastern policy we shall be taking the wise course of attacking them all along the line.”53

He urged a complete change of policy in relation to the north, from one of aggression to one of conciliation. In particular, he urged that: “The ‘Outrage’ propaganda should be dropped in the Twenty-Six Counties. It can have no effect but to make certain of our people see red which will never do us any good.”54

On 19 August, the Provisional Government accepted the committee’s recommendation that: “It was considered desirable that a peace policy should be adopted in regard to future dealings with the North and Ulster.” Collins was not at this meeting although the decision was conveyed to him. Three days later, he was dead.55

Publication of Hassan’s work was cancelled and it is believed that only 18 printed copies of the pamphlet survived – one was sent to Bishop MacRory, another to Joseph Devlin, Nationalist MP at Westminster for Belfast West. Another copy surfaced in 1997 and at the urging of historian Andrew Boyd, it was used by Tom Donaldson to re-publish Hassan’s original document.

Hassan dedicated the pamphlet: “To the many Ulster Protestants who have always lived in peace and friendliness with their Catholic neighbours, this little book dealing with the acts of their misguided co-religionists is affectionately dedicated.”56

It largely consists of short descriptions of hundreds of the incidents which occurred in the city. The vast majority of those chosen by Hassan were ones in which Catholics were the victims, including the notorious McMahon family killings and the particularly vicious murders committed by police in Arnon St in April 1922. Interspersed with these are critical reviews of the unionist press and of the conduct of politicians in London and Belfast.

The funeral of the McMahon family (Illustrated London News, 1 April 1922)

However, Hassan’s most venomous condemnation was reserved for the Special Constabulary, who he described as:

“…local men, recruited for the most part from the dregs of society, brought up from their earliest years in an atmosphere of anti-Catholic bigotry, taught both by their political and religious leaders that their Catholic neighbours are their only enemy, and inflamed by the subtle innuendoes and brazen lies of the most malignant Press in the world.”57

His prose could be florid and emotional, “…the pogromists broke loose on their fiendish work in Belfast” being a typical example.58 By the time the northern government was established in June 1921:

“Already for practically a whole year, the Catholics of Belfast and of many other places had been suffering at the hands of who now demanded their allegiance and co-operation the agonies of a wholesale persecution such as no Christians in any part of the world outside Turkey have been subjected to in modern times.”59

Hassan’s work was clearly intended as propaganda for an international audience. He particularly highlighted violence inflicted on Catholic ex-servicemen, pleading that having served the Empire in wartime they now deserved protection in peacetime. Considering his clerical background, it is not surprising that he also emphasised the frequent attacks on Catholic churches and presbyteries, particularly those on St Matthew’s in Ballymacarrett.

His prose style bears interesting comparison with that of another priest, Patrick Gannon, who wrote an article titled In the Catacombs of Belfast for the Jesuit journal Studies in June 1922. Gannon observed of the city’s Catholics: “By day they are at the mercy of the lonely apache with a revolver in his pocket or the mob which wants to drive them from their employment; by night they live in terror of the Specials, who are now their most dreaded enemies.”60

However, the IRA is mentioned only four times in the entire pamphlet: twice in a letter from Craig to Collins quoted by Hassan, once in the text of the second Craig-Collins Pact which Hassan reproduced in full and only once in his own text. He cannot have been unaware of the IRA – during the Truce, they had used St Mary’s Hall, mere yards from his church in Chapel Lane, as their Truce Liaison Office and a police raid on the hall in February 1922 captured documents listing many IRA members who had attended training camps.

The part of Hassan’s pamphlet that has subsequently been most cited by historians is his list of 455 people – 267 Catholic, 185 Protestant and 3 “unascertained” – who were killed in Belfast from July 1920 to June 1922. An identical but handwritten list was included by the Brigade Committee of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade among their submissions to the Military Service Pensions Board in the 1930s, so a copy of the pamphlet was evidently then in circulation in Belfast republican circles.61

However, in his list, Fr Hassan is guilty of both sins of commission and sins of omission. The victims of a number of accidental shootings are included – these involved the children or friends of policeman killed when service weapons were unintentionally discharged in their homes. Another involved a Private “Arthur Boundary” – in fact, Frederick Bundy – fatally shot in a barracks when a fellow soldier was cleaning his rifle. Counting these as victims of the pogrom is at least questionable.

“Constable” – actually, Sergeant – Sam Lucas is listed as having died on 4 November 1920; however, Sergeant Lucas had been wounded in Tempo, Co. Fermanagh, so while he died in Belfast from violence, he did not die from Belfast violence.

William Bell is listed as having been killed on 1 December 1920, but he did not die from political violence at all – a contemporary newspaper describes how a wall collapsed on the unfortunate Bell during a thunderstorm. History does not record if it was a Protestant wall or a Catholic wall.

Hassan omitted the names of three Protestants killed by an IRA bomb thrown onto this tram on 22 November 1922 (Illustrated London News, 3 December 1921)

Much more seriously, Hassan’s list fails to include the three Protestants killed when, on 22 November 1921, the IRA threw a bomb into a tram in Corporation St carrying shipyard workers home. The attack itself is mentioned in passing in the text, but to omit the names of the victims of the IRA’s first such indiscriminate sectarian attack is a huge failing. Two days later, a second tram, bound for the Shankill Road, was bombed on Royal Avenue and four killed – but their names are included.

But while criticisms can be levelled at Hassan’s work, the central argument of his pamphlet remains valid: from the initial workplace expulsions of July 1920, through to the subsequent evictions, house-burnings, woundings and – above all – killings, the overwhelming majority of the political violence in Belfast in the Pogrom period was perpetrated against Catholics and nationalists.

Suppressing the publication of Facts and Figures allowed their plight to be quietly forgotten by the Provisional Government.

From Capitalism to Cannibalism – An Account of the Belfast Capitalist Pogrom

Hassan was not the only person to write a pamphlet about the Pogrom in 1922.

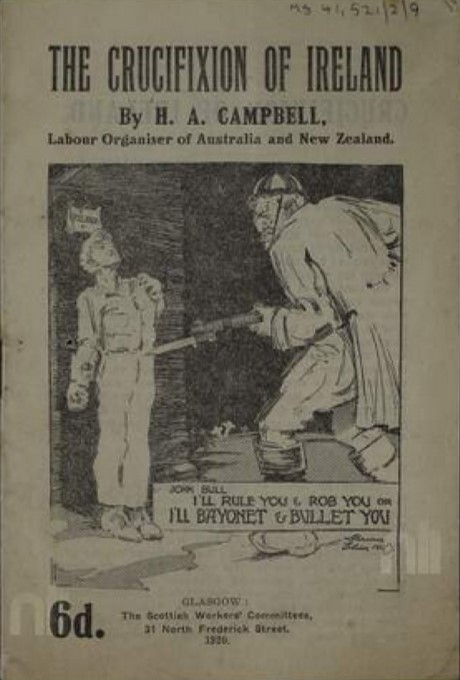

Harry Arthur Campbell was a New Zealand socialist, born in Australia, who emigrated to Glasgow; his father originally came from the north of Ireland. He spent a month in Ireland during 1920 and recounted what he had seen in a pamphlet. He clearly understood the value of an eye-catching title, as the pamphlet was titled The Crucifixion of Ireland.62

L: Harry Arthur Campbell; R: front cover of his pamphlet The Crucifixion of Ireland (© National Library of Ireland)

In 1922, he wrote another pamphlet, this one relating to the Pogrom; it does not appear to have ever been published and now exists only as a typescript draft in the Military Archives’ Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents collection. Campbell was still fond of an attention-grabbing title: this pamphlet was to have been called From Capitalism to Cannibalism – An Account of the Belfast Capitalist Pogrom.63

This title reflected his personal conviction that: “No Christian of any denomination, nor Jew, nor Agnostic would murder Catholics on account of their religion. That is Cannibalism.”64

The text can be dated to the autumn of 1922 – on page 80, he referenced the killing of Peter Mullen in the Crumlin Road Picture House, which happened on 29 August; the typescript is 125 pages long, so he clearly could not have completed it before September or October 1922.65

Campbell had been a street orator and the rhetorical style, overblown for emphasis, that he would have developed for that purpose is evident in his prose. He was by no means a neutral observer – on the second page, he nailed his colours to the mast:

“I have some sympathy for the poor unfortunate Ulster Orangemen … They are just what their birth, education and training have made them. They had their purile [sic] minds inoculated, poisoned and ruined with sectarian bigotry and religious hatred in their infancy, and they have suffered from arrested mental development ever since.”66

Nor did he hold back in the rest of the text, although as we shall see, his inclination towards hyperbole could sometimes lead him to lose sight of the facts.

His political analysis was very much in the mould of Jim Larkin and James Connolly and while he scorned Orangemen, he championed the Protestant working class: “I believe the Protestant female workers of Belfast are the most disgracefully sweated and callously treated white women on the face of the Earth.”67

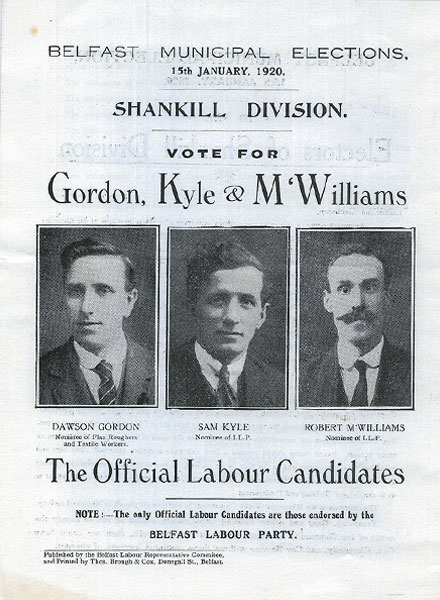

He gave an approving account of the 1919 Belfast engineering strike and described with gusto Labour’s success in the city’s Corporation election of January 1920, when ten Belfast Labour Party and two independent Labour candidates were elected: “At the declaration of the Poll a huge crowd of workers congregated inside the sacred grounds of the City Hall, and sang the ‘Red Flag’ – the song of universal brotherhood – this made the loyal Orange Capitalists weep, and that night not a heathen Capitalist went to sleep.”68

Election poster for Belfast Labour Party candidates in Shankill ward, January 1920

He worked himself into a state of frothing fury when providing an account of the 1920 Twelfth:

“All the loyal Orange Capitalists, Imperialists, employers, labour sweaters, profiteers, gombeenmen, freebooters and politicians appeared on the scene in bright, full regalia, accompanied by their wives and families. Huge crowds of excited perspiring loyal subjects, wearing Orange sashes and bright, gay colours, marched in a long procession to the old tune of the ‘Boyne Water.’”69

Campbell was not a man to let the truth get in the way of a good polemic: when he came to the shipyard expulsions of 21 July 1920, he claimed that “Many were drowned, others were killed in the water while trying to escape.” However, nobody was actually drowned or killed in the Lagan on that day.70

His sympathies were very much with Belfast’s nationalists: “These Catholic homes were broken up, destroyed and the inhabitants driven out on to the streets to starve by the loyal Orange Capitalists and Imperialists.”71

Unsurprisingly, given his politics, he paid particular attention to the Belfast Labour Party’s campaign in the 1921 general election:

“But the Belfast loyal Orange Capitalists and the patriotic employers had a dreadful objection to their political policy and economic principles … they decided to stop it from going any further. So they organised several thousands of loyal servile Orangemen and instructed them to ‘take the law into their own hands’, break up all the Labour Candidates’ meetings, destroy their electioneering literature, keep the Labour voters out of the Polling Booths on Election Day and give the Labour Candidates no chance to win.”72

Loyalist shipyard workers on their way to break up a Labour election meeting (Illustrated London News, 29 May 1921)

Roughly half of the typescript consists of accounts of individual incidents involving killings, woundings and forced evictions that occurred during 1922, with lengthy accounts of the McMahon family killings and those in Arnon St.

For these, Campbell appears to have relied heavily on the Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities) published by the Provisional Government to highlight what was happening in the city. Apart from reports sent to Dublin by the IRA and by Collins’ investigators, these bulletins were also based on detailed reports compiled by the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee, which in turn drew on the information being gathered at the time by Hassan. Therefore, there are clear overlaps and similarities in terms of content between Campbell’s and Hassan’s works, although Campbell also includes detailed descriptions, based on press reports, of incidents further afield in Derry, Dungiven, Portadown, Newry and Cushendall.73

Campbell appeared to have reached a conclusion when he wrote this summary:

“The Belfast Loyal Orange Capitalists who have hired the assassins and controlling [sic] the pogrom, are only puppets doing the dirty work in Ireland of the British Capitalists and Imperialists. The Capitalists Agents in Belfast are using religion as the most convenient, reliable and effective instrument to create war in order to deprive the common people, smash organised labour movements of Ulster, get rid of the active socialists, militant trade unionists and exterminate Catholics to make room for servile orange loyal wage-slaves.”74

He would have done better to stop writing at that point.

However, in another parallel with Hassan, he then embarked on a review of the protests raised by southern Protestants over events in Belfast, but whereas this occupied just five pages of an appendix in Facts and Figures, Campbell devoted eleven pages to it, followed by another eight consisting of newspaper accounts of Protestant testimony as to the tolerance of southern Catholics towards them. Thus, almost a fifth of his text consists of establishing an argument that sectarian hatred and violence were uniquely northern phenomena.

But, having turned his attention southwards, Campbell then took a bizarre detour by providing a preposterous, delusional and utterly fictitious account of the Bandon Valley killings in Cork in late April 1922:

“So the Royal Orange Capitalists decided to create a religious war in the South of Ireland … They sent two consignments of guns and ammunition from Belfast to Cork. They then sent a gang of Ulster Orange gunmen to County Cork to do their dirty work. Late on Wednesday night, April 26th, 1922, the Loyal Orange gunmen assassinated Mr. Francis Fitzmaurice, Solicitor, Mr. T.W. Gray, Chemist and Mr. T. Buttimer, retired draper, in Dunmanway … The I.R.A. caught one of the Ulster Orange assassins red-handed in the district and when put up against the wall and given opition [sic], he revealed the Capitalists plot.”75

Perhaps exhausted after this flight of fantasy, Campbell did finally reach a conclusion. However, the merit of some of his earlier analysis was negated by his use of an appalling racist stereotype which suggested that, despite his apparent socialist rhetoric, he still had much to learn about international solidarity:

“The Capitalists and Imperialists who have organised the Belfast pogrom, and who are instrumental in killing Catholic men, women and children in Ulster for more profits and greater political and economic power, are far more dangerous heathens and treacherous cannibals than the aborigines of New Guinea who kill human beings for blood.”76

Although such analogies were by no means uncommon at the time – similar tropes relating to Turks, Armenians and various Balkan nationalities were often repeated by mainstream politicians and newspapers (and, as noted above, by Hassan) – Campbell’s descent into racism is remarkably out of place in a discussion of sectarianism in Belfast.

Summary

There are some interesting commonalities between several of the works considered here.

While all involve the Pogrom to some extent, not all were actually published, which possibly tells its own story in terms of a desire to suppress discussion or even memory of the events of 1920-1922: The Long Dark Street was broadcast but never published either on its own or in a collection of Thompson’s work, Facts and Figures was only barely published in the sense that it was immediately withdrawn, while From Capitalism to Cannibalism never saw the light of day in print.

Although it reflects the limited extent of writings about the Pogrom, and especially the fact that Thompson wrote two of them, it is striking that three of these six works view the events in Belfast through a socialist prism and are rooted in the city’s labour tradition, particularly that of the Protestant working class. In contrast, McLaverty and Hassan were solely concerned with how events affected the city’s nationalist population.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some literary devices were shared. Both McLaverty and Thompson used football matches between boys of the opposing communities to point out that sectarian divisions are taught rather than innate, while both used street meetings encountered by chance as vehicles for voicing the authors’ own anti-sectarian messages.

It is also no surprise that the shipyards feature strongly in all six pieces – after all, that was where the Pogrom initially erupted, with loyalist shipyard workers acting as the shock troops of unionism.

But critically, they targeted both nationalists and “rotten Prods,” which meant that “a brief flowering of anti-sectarian, working-class politics lay smashed between the hammer of loyalist violence and the anvil of economic depression.”77 Indeed, the fact that Protestant trade unionists and socialists were attacked, particularly in July 1920 but also later, is one of the key reasons why I have argued that what happened in Belfast in these years does not meet the dictionary definition of “pogrom.”

Although Over the Bridge is ostensibly not about the Pogrom at all, it can be read in two ways. From the characters’ perspective, the mob violence of July 1920 is a painful memory which is about to be – and ultimately is – re-visited at some later, unspecified, date. However, to its audiences, the play may well have been experienced as a direct re-enactment of July 1920, an uncomfortable historical drama about those events themselves.

In that play – and also, in a less explicit way, in The Long Dark Street – Thompson mourns the destruction of the “rotten Prod” tradition in his community. McLaverty also mourns, but in a different, non-political, sense: he laments the loss of childhood.

The novel gives him space to reflect in beautiful prose on idyllic, pure aspects of Colm’s young life. But in the end, all the carefree family excursions, all the schoolboys’ boisterousness, all the simple yet exciting treasures of Smithfield market are negated and crushed forever when the relentless violence of the Pogrom finally erupts into his home.

References

1 https://www.linenhall.com/michael-mclaverty-short-story-award-2023/

2 Michael McLaverty, Call My Brother Back, (Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 2003), p75.

3 Ibid, p79-80.

4 Ibid, p115.

5 Ibid, p130.

6 Ibid, p 130-131.

7 Ibid, p134.

8 Ibid, p136.

9 Ibid, p137.

10 Ibid, p142.

11 Ibid, p149-150.

12 p152.

13 p154.

14 Belfast Telegraph 13 April 1921; Belfast News-Letter 25 April 1921.

15 McLaverty, Call My Brother Back, p160

16 Ibid, p163.

17 Ibid, p163.

18 Ibid, p171.

19 Ibid, p172.

20 Ibid, p174.

21 Ibid, p184.

22 Ibid, p184.

23 Ibid, p191.

24 Sam Thompson, A Belfast Protestant Childhood, RTÉ Radio broadcast, 26 June 1962, https://www.rte.ie/archives/2017/0620/884168-sam-thompson-a-self-portrait/

25 Connal Parr, ‘The pens of the defeated: John Hewitt, Sam Thompson and the Northern Ireland Labour Party’ in Irish Studies Review, Volume 22 Number 2 (April 2014), p148.

26 Sam Thompson, The Long Back Street, typewritten script, n.d., Belfast Central Library, Sam Thompson Archive, 6F(ii), p1. I am grateful to Connal Parr for pointing me in the right direction to view this work.

27 Ibid, p12.

28 Ibid, p14.

29 Ibid, p20.

30 Ibid, p23.

31 Ibid, p30-31.

32 Ibid, p33.

33 Ibid, p34.

34 Parr, ‘The pens of the defeated,’ p149.

35 Ibid, p150.

36 Sam Thompson, Over the Bridge (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 1970), p22.

37 Ibid, p30.

38 Ibid, p44-45.

39 Ibid, p47.

40 Ibid, p76.

41 Ibid, p79.

42 Ibid, p94.

43 Ibid, p98.

44 Ibid, p101.

45 Ibid, p107-108.

46 https://www.poetryascommemoration.ie/poems/the-belfast-pogrom-some-observations-by-paul-muldoon/

47 Kieran Glennon, ‘Facts and Fallacies of the Belfast Pogrom’ in History Ireland, Volume 28 No.5 (September/October 2020)

48 J. A. Gaughan, Alfred O’Rahilly – Public Figure (Dublin, Kingdom Books, 1986), p170.

49 Ibid, p169.

50 Ibid, p169.

51 Meeting of Northern Advisory Committee, 11 April 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), North East Advisory Committee, TSCH/3/S1011.

52 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1920-08-06/7/

53 Ernest Blythe to North East Policy Committee, 9 August 1922, University College Dublin Archive, Ernest Blythe Papers, P24/70.

54 Ibid.

55 Minutes of Provisional Government meeting, 18 August 1922, NAI, Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

56 G.B. Kenna (pseudonym of Fr John Hassan), Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922, (Dublin, O’Connell Publishing 1922; reprinted, Belfast, 1997), p2.

57 Ibid, p65.

58 Ibid, p36.

59 Ibid, p55.

60 Patrick Gannon, ‘In the Catacombs of Belfast’ in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Volume 11, No. 42 (June 1922), p279-295.

61 Kenna, Facts and Figures, p101-112; Military Archives (MA), Military Service Pensions Collection, MSPC/RO/402 3rd Northern Division, No. 1 Brigade (Belfast) HQ.

62 Labour Leader (London), 15 February 1917; H.A. Campbell, The Crucifixion of Ireland (Glasgow, Scottish Workers’ Committees, 1920), National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ceannt and O’Brennan Papers, Ms 41,521/2/9. More information about Campbell can be found at https://irishdiasporahistory.wordpress.com/2018/10/08/an-australian-sinn-feiner-on-the-red-clydeside-ireland-as-a-site-of-political-pilgrimage/

63 H.A. Campbell, From Capitalism to Cannibalism – An Account of the Belfast Capitalist Pogrom, unpublished typescript, n.d. (autumn 1922?), MA, Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents, Mrs Austin Stack Collection, BMH-CD-199.

64 Ibid, p2.

65 Ibid, p80. Campbell’s typescript had numerous spelling mistakes, but these and his punctuation have been left unchanged.

66 Ibid, p2.

67 Ibid, p3.

68 Ibid, p6.

69 Ibid, p7.

70 Ibid, p10.

71 Ibid, p12.

72 Ibid, p13.

73 Dáil Éireann Publicity Department Weekly Irish Bulletins, NAI, NEBB/1/1/4. Parts of various Belfast Catholic Protection Committee reports exist in numerous archives, but the most extensive collection appears to be that in NLI, Art Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee, Ms 8,457/12.

74 Campbell, From Capitalism to Cannibalism, p87.

75 Ibid, p122-123.

76 Ibid, p125.

77 Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, ‘“No Such Sight Has Been Seen in Belfast Since Dissenter and Catholic United in 1791”: the Workers’ Union and the Belfast Labour Party’ in John Cunningham & Terry Dunne (eds), Spirit of Revolution – Ireland from Below, 1917–1923 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2024), p200.

Leave a comment