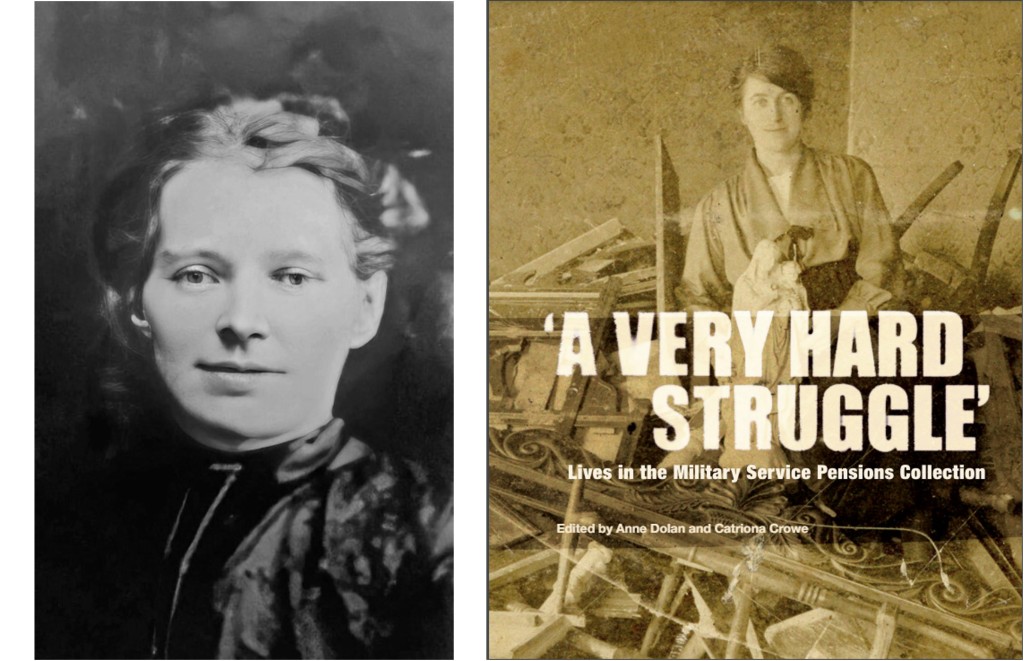

(L) Annie McNamara, killed in Belfast on 29 November 1921 (photo courtesy of Aisling Heath and Pat McGuinness); (R) front cover of “A Very Hard Struggle” (image reproduced courtesy of Military Archives)

This post was directly inspired by the evocative essays in “A Very Hard Struggle, Lives in the Military Service Pensions Collection”, edited by Anne Dolan and Catriona Crowe, published by the Department of Defence in 2023.1

My thanks to Cécile Chemin, Project Director – Military Service (1916-1923) Pensions Collection at the Military Archives, for her valuable guidance in referencing documents from this vast, unique resource.

Estimated reading time: 40 minutes.

“Had he been killed while in the British Army she would have been provided for”

On 25 September 1920, Constable Thomas Leonard became the first policeman to be killed by the IRA in Belfast since the start of the Pogrom – he was shot dead during an attempt to disarm him and another policeman at the junction of the Falls Road and Broadway. That night marked the first appearance of what came to be known as the police “murder gang” – the homes of three republicans were visited by masked men and a resident killed in each as a reprisal for the killing of Constable Turner.

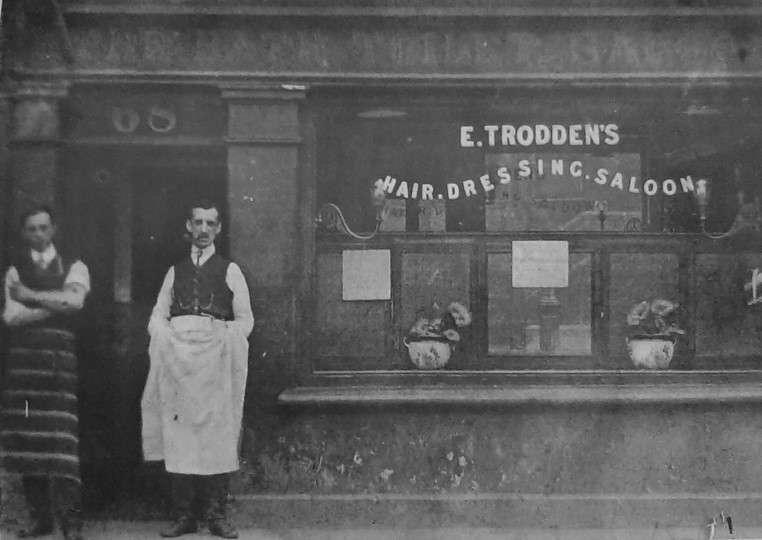

One of those killed was widower Ned Trodden, who had joined the Irish Volunteers on their foundation, was still in the IRA in 1920 and owned a hairdressers on the Falls Road. He was dragged into the back yard of his home and shot dead by his assailants.

Ned Trodden (R) in front of his hairdresser’s shop (photo courtesy of Jimmy McDermott)

In May 1922, his three sons, Edward, Charles and Michael, applied for £6,000 compensation under the terms of the UK Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts. As outlined in a previous blog post, because such compensation payments would represent a charge on the local authority, thus increasing the burden on ratepayers, magistrates could often be miserly in their awards. Trodden’s sons fared no differently, being awarded only £500 between them.

Trodden’s sister, Elizabeth, had been living with him and his sons at the time of his killing, supported by him and in return, acting as their housekeeper. In February 1924, she applied for a dependent’s allowance or gratuity under the terms of the Army Pensions Act 1923. The following June, having got no response, she wrote to the Minister for Defence: “…I am in urgent need. My nephew (the eldest son of my murdered brother) is at present in the Free State ‘on the run’ + is unemployed + therefore cannot contribute to my support.”2

She told the minister that the police were still hounding the surviving family members, nearly four years after Trodden’s killing:

“It is utterly impossible for me to keep a business going here, owing to the repeated raids of the forces of the Northern Government, who have never ceased to harass + annoy us since the date of my brother’s murder … The latest raid on our house took place on 31st May 1924 + my nephew left Belfast on 2nd June 1924.”3

The rock on which her application foundered was Section 13 of the 1923 Act – this specified that, “No pension, allowance or gratuity shall be payable under this Act to or in respect of any officer or soldier on account of any wound or death which has been the subject of a decree for compensation under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts, 1919 and 1920.”4

Whether the compensation awarded was adequate was immaterial; whether it had been awarded to the person making the claim was also immaterial; all that mattered was whether some compensation had been awarded to anyone.

No such disqualification existed in relation to money that an applicant might previously have received from the Irish White Cross. This was a fund established in February 1921 by the American Committee for Relief in Ireland, aimed at “…alleviating the suffering of the civilian population in Ireland. Though established by sympathisers with the Irish cause in the war against Britain, the fund publicly claimed impartiality and neutrality in its relief provision.” Almost half of the total relief it dispensed went to Belfast.5

Therefore, the intent of Section 13 of the 1923 Act was not to prevent double-payment on principle, but to specifically debar those who had already gone running to the British for financial assistance.

The claim brought by Elizabeth’s nephews in 1922 was to prove her undoing. She was asked to provide a copy of the court’s decision, which she did in September 1924:

“Please find enclosed copy of decree requested by you in your communication of Aug 23rd. I learn from same that the sum of £50 was awarded to me. This I may say is the first information I have had of same but as the sum of £50 was drawn to defray lawyers expenses it was probably my award that was used.”6

Although the fact that she had been awarded £50 evidently came as news to her, three months later, she was bluntly informed: “As the matter has been the subject of a decree for compensation under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts 1919 and 1920 your claim is not admissible.”7

Alexander Hamilton had served for seven years in the Inniskilling Fusiliers regiment of the British Army. After being demobilised, he joined the IRA but while on picket duty, he was killed during rioting on 10 July 1921, the day before the Truce – he “merely glanced round the corner of Conway Street when a Unionist sniper at the Shankill end of that thoroughfare sent a bullet through his head.”8

His mother, Mary Ann, applied for a dependent’s allowance or gratuity in November 1923, but her application was doomed from the start, for the same reason as Elizabeth Trodden’s – Mary Ann admitted in the form that she had been awarded £150 under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts, although the actual award had been £350. Her application was rejected on that basis.9

However, she had not given up. When the Army Pensions Act 1932 was passed, she sought an application form to lodge a new claim, only to be told once more that her previous compensation award meant that “no action can be taken in your case.” She was not even sent a form.10

In 1936, a friend or neighbour, Jack McCusker, took up her case – writing to the Department of Defence, he raged that, “This woman is now left without any means or support, and the country for which he sacrificed his life for has ignored her claim for assistance had he been killed in the British Army she would have been provided for.” He was referred to the rejection letter previously sent to Mary Ann.11

In 1937, she tried again, this time pointing out that the killing had ultimately robbed her of her husband as well as her son: “My late husband who was at that time laying under medical treatment died shortly afterwards from more or less a broken heart through loosing under such sad circumstances one of the finest sons desired.” She even tried pleading that, at her age, she would not be around long enough to create a lasting liability for the Free State taxpayers: “I may not live long in this dreadfull state as my age is 73 years so if you consider my application worthy then probably it will only be for a short period that I should enjoy the hospitality of whatever grant may be allotted to me.”12

She, too, was referred back to the rejection letter previously sent to her. After this fourth such rebuff, she stopped writing.

Rioting in the Marrowbone, where Owen Moan was killed (Illustrated London News, 9 October 1920)

Owen Moan was killed in Glenview St in the Marrowbone on 29 August 1920. His widow, Jane, who had been completely dependent on his labourer’s earnings, encountered other forms of bureaucratic intransigence in her pursuit of an allowance or gratuity. In August 1935, she wrote to the Department of Defence, requesting an application form to make a claim under the Army Pensions Act 1932. She was told that the closing date for applications had been 9 December 1933.13

A new Army Pensions Act was passed in 1937, so she applied under this. As part of the process, she was asked to provide the names of witnesses who could verify Moan’s membership of the IRA and the circumstances in which he was killed. She nominated William Morrison, who told the department that Moan had been killed “while in action with Crown forces;” he knew this as he had been “present when he got shot.”14

Two months later, another IRA member from the same area, Desmond Crean, was interviewed by the department’s Advisory Committee in pursuit of his own application for a military service pension; he told them, “…there were two or three very violent attacks on the district and there was two boys killed. Moan was shot – a member of ‘A’ Company.”15

Despite both men’s testimony, Jane was told a few months later that, “The deceased was not at any time a member of any of the organisations to which Part II of the Army Pensions Act of 1932 applies.” She was given no rationale for this decision.16

Closing dates were not only enforced in relation to the receipt of applications, as Ellen Walker discovered. Her son, John, was killed in Short Strand on 20 April 1922, but in the early legislation, there was also a closing date for deaths and he was killed too late to qualify:

“…an application from Mrs Walker was considered under the Army Pensions Act, 1927. In accordance with the terms of the Act an award may be made to dependents of deceased volunteers in cases such as Mrs. Walker’s only when the deceased was killed prior to the 1st April 1922. As the death of the deceased occurred subsequent to 1st April 1922, an award could not be made to Mrs. Walker under the terms of the 1927 Act.”17

However, this decision had not been communicated to her. In 1934, she tried again, this time under the 1932 Act, only to be told, “…an application on the prescribed form under the Act should have been made before 9th December 1933.”18

She made a third application in 1937 under the terms of the Army Pensions Act of that year. This time, she was successful and in 1941, 19 years after the killing of her son, she was finally awarded a gratuity of £75.19

The gratuities paid to the bereaved certainly appear modest, to put it mildly, and applicants who were successful still struggled to make ends meet with what they were given.

Séamus Ledlie was killed in Norfolk St in Clonard on 11 July 1921, just ten minutes before the Truce was due to come into effect. In 1924, his father, Hugh, applied for an allowance or gratuity under the 1923 Act. The local branch of the St Vincent de Paul Society reported to the Army Pensions Department in Dublin that he was out of work through an accident and could not work owing to ill-health; he had seven other children still living, four of whom were still in school, two working and one “on the bureau” (receiving unemployment assistance). On this basis, he was awarded a gratuity of £100.20

Within five years, that money had run out, so he appealed directly to W.T. Cosgrave, President of the Free State’s Executive Council, or government, pleading for additional help:

“My dear sir in the year 1920 i was working in a unionist firm and i was hit with a iron pike and called a shan faner [sic – Sinn Féiner] well sent to a light job and the was worse for the turned on a gass jet to poison me well sir the sent me to the queens iland to get me killed but thank god i am here yet but hungary … I have only 6/- [six shillings] disablement benefit to live on and i am not 60 yet.”21

The response by the Ministry of Defence was cold: “…the Minister regrets that no further award can be made to you.”22

“It’s only the workhouse for me now as the money I got is all finished”

The various Army Pensions Acts specified that payments could only be made to members or the dependents of members of combatant organisations. As a result, applications relating to civilians who had been killed or wounded were routinely rejected on the basis that the victim “was not a member of any of the organisations.”

Over the course of the Pogrom, 88% of the nationalists killed in Belfast were non-combatants. Although they were ultimately unsuccessful, applications by the families of these dead civilians still provide useful insights into what all those left mourning went through, irrespective of whether their loved ones had been combatants or not.

Effigies hung on the Newtownards Road in Ballymacarrett (Illustrated London News, 4 September 1920)

Francis McCann was killed in Seaforde St in Ballymacarrett on 26 August 1920 – according to his sister, Catherine McGovern, he had been helping to stop an attack on the area by loyalists. She herself had been wounded a few days earlier but was concerned for her brother’s safety:

“I myself was wounded in the heel and maimed for life from this wound I still suffer. I demanded my discharge from hospital on Wednesday 25th August 1920 … the reason for me coming out of hospital was because the Orangemen had his coffin already made and hoisted on a lamp standard with a placard attached for Fenian McCann.”23

Although her brother had been killed by the British Army, local loyalists inflicted more psychological violence on her after the killing:

“But when they heard of his death they sent word they would burn his corpse on the day of his funeral and to avoid this his remains had to be kept six days which meant a lot of expense to me even without any insurance society. So you see his death was one of the most trying experiences I have ever met.”24

Alexander Hamilton’s father was not the only grieving relative to die of a broken heart.

On the night of 29 November 1921, there was a thud at the door of Annie McNamara’s house in Keegan St in the Market. When she opened the door to investigate, a bomb which had been thrown by loyalists from behind a nearby railway wall exploded, fatally wounding her.

In 1933, her son, Thomas, wrote for an application form, stating that, “My father was left a physical and nervous wreck, and never fully recovered from the sad blow, and died two years ago from the effects.”25

Annie had evidently been the glue holding the family together before her killing. Two other sons, John and Francis, had been members of the IRA – both emigrated to the USA:

Annie McNamara was killed by a loyalist bomb on 29 November 1921 (photo courtesy of Aisling Heath and Pat McGuinness)

“…we had to sell our home to enable them to do so … My youngest sister Annie McNamara was left on my hands for a couple of years. I had to send her to America also … As you can see by this, we suffered through the scattering of our home + family to the world.”26

On 29 August 1920, Robert Lynch was killed by British troops in Townsend St. For his mother, Mary Ann, “…he was my wholly support I had in this world as his father was a infilead he gave me 2 pounds aweek.” She received a £100 grant from the Irish White Cross following her son’s killing, but by 1932, was facing extreme poverty: “I have no pension as my husband never worked in his life now I am penniless kind sir I should like you to try and doe something for me as its only workhouse for me now as the money I got from Irish Free State is all finished.”27

Asked by the department to confirm his membership of the IRA, she stated “he was connected with fireannion [sic – Fianna?] boys during trouble in Ireland.”28

After a protracted saga lasting almost five years, involving an application form being completed but not posted, posted but not received, received after all but after the closing date, Mary Ann re-submitted the form but in doing so, planted the seed of her own downfall – she said that her son’s former company Captain, Pat McCarragher, could confirm her son’s membership of the IRA. Unfortunately for her, McCarragher told the Military Service Registration Board (MSRP) that “Robert Lynch never was attached to my unit (‘A’ Company, 1st Batt) at any time during 1919-1920.”29

The following year, Mary Ann was told, “The deceased was not at any time a member of any organisation to which Part II of the Army Pensions Act, 1932 applies.”30

Wilhelmina Burns was killed in Upton St in Carrick Hill on 17 May 1921. Her widowed mother, Elizabeth, made a half-hearted attempt to connect the killing to the independence struggle: in her letter requesting an application form, she included the curious phrasing, “I had a daughter killed through the activities of the IRA.” However, the inquest into Wilhelmina’s killing heard that she had died when a policeman, pursuing a rioter, fired a shot at him but the bullet hit her as she stood in her doorway.31

As she was aged only 15 when killed, there was no question of her being a member of Cumann na mBan, so Elizabeth received the usual “not a member of any of the organisations” rejection.32

Daniel Rogan was a bystander fatally wounded in crossfire when the IRA killed a member of the police “murder gang,” Sergeant Christy Clarke, on 13 March 1922. His brother, Thomas, made a blatantly dishonest attempt to benefit financially from the killing.

When writing for a form to make an application under the 1932 Act, he said his brother ”…was killed by enemy forces … The inquest was held in Victoria Barracks and as it was held that he was concerned in the shooting of Sergt. Christopher Clarke, no compensation could be claimed from the city.”33

Sergeant Christy Clarke: when the IRA killed him on 13 March 1922, Daniel Rogan was fatally wounded by crossfire

In fact, Rogan’s killing was investigated by a military Court of Inquiry; a policeman who had been accompanying Sergeant Clarke testified that he had fired at their attackers – he had been armed with a .38 revolver. But the bullet retrieved from Rogan’s body in hospital was of .45 calibre. Rogan’s death certificate, which his brother sent to the department, stated that he died of “a gunshot wound inflicted by a .45 calibre bullet fired by armed men who were attacking the Police,” that being the verdict of the Court of Inquiry. This ballistics evidence directly contradicted Thomas Rogan’s assertion.34

When he completed the application form in July 1933, he also inflated the circumstances of the killing: “…deceased was shot by member of the Royal Irish Constabulary as a reprisal.” He also repeated his claim that no compensation had been paid. However, in November 1922, his mother had lodged a claim for £1,500 compensation for the death of her son in the Belfast Claims Court under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts; her barrister told the court that “he was murdered by the same men who had killed Sergeant Christopher Clarke.” She was awarded £75 and a further award of £15 for funeral expenses was made to her surviving son – Thomas.35

Joe Cullen was named by Thomas Rogan as his dead brother’s Battalion O/C, but Cullen put the final nail in the application when he told the MSRP that the dead man “Did not serve under my command + from enquiries I cannot find him having any connection with the military movement.” The application was rejected on that basis.36

“He was anointed for death before leaving”

Some of the bereaved had the additional emotional turmoil of seeing their relatives die slowly as they watched – these were the families of internees who had developed severe illnesses while imprisoned.

The internment ship SS Argenta

John O’Donnell was arrested on 29 May 1922 and interned on the prison ship SS Argenta until October 1923, when he was released on medical grounds. According to a letter written by his widow, Brigid, to the Minister for Defence in August 1932, “He was anointed for death before leaving … When he came home he was in a dying condition.” Agonisingly for both of them, he lingered for over 18 months before finally dying on 16 June 1925.37

She used the same phrase when applying for an allowance or gratuity under the 1932 Act, saying he had been released “…in a dying condition owing to brutality confinement ill nourishment also the unsanitary conditions while imprisoned in the cages of the Argenta.” After his death, she received a grant of £150 from the Irish White Cross.38

Dr Henry Russell MacNabb, who had served as a Medical Officer in the GPO during the Easter Rising, then had the same role in the IRA’s Belfast Brigade and subsequently the 3rd Northern Division, confirmed that O’Donnell had “contracted tuberculosis while a prisoner” leading to “acute general tuberculosis … 10 days before his death.”39

Asked by the Army Pensions Board to investigate Brigid’s circumstances, a local priest, Fr John McKee, told them her entire income consisted of a widow’s pension of 15/- a week and a payment of 10/- a week which she was receiving from the Irish White Cross, as she still had a daughter aged 12.40

The following month, the board decided that O’Donnell’s death was due to disease contracted while on military service; Brigid was given an annual allowance of £67/10/- for herself as well as an additional allowance of £18 a year which would continue until her daughter was aged 21.41

Hugh Hennon was another internee: arrested on 31 May 1922 and interned on the Argenta from June 1922 to January 1924, he was then transferred to the internment camp at Larne Workhouse in January 1924 and released the following month. He died nine months later on 21 September.

His mother, Mary Josephine, requested an application form for the 1932 Act, saying, “During this time on the ship my son Hugh suffered much from the close confinement + finally as the result of a hunger strike his health became totally undermined + on his release on Feby 4th 1924 he was a complete physical wreck.”42

The family doctor, Dr Bradley, said Hennon had developed nephritis (a kidney infection) while interned but had received no medical treatment, so by the time he was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital “his case was hopeless.”43

According to Mary Josephine’s application form, she, like Brigid O’Donnell, had also received a grant from the Irish White Cross, though only of £100. Her form contained one notable quirk – it was witnessed by her other son, Laurence, who had been arrested and interned at the same time as his brother; by 1933, he was a Garda in Athlone, one of the professions specified on the form for witnessing the applicant’s signature. In effect, this was a family application.44

Eight months later, the Army Pensions Board recommended the payment of a £75 gratuity, but the Department of Finance protested over the size of the award – they said that in view of the fact that Mary Josephine was in receipt of 10/- a week widow’s pension and also had two daughters working in clothing factories, each contributing £1 a week at home, the amount was excessive. However, the Department of Defence held firm and the award was confirmed in October 1934.45

“I took a pleurisy and was hovering between life and death for a week”

While the killing of Constable Leonard in September 1920 led directly to the reprisal attack in which Ned Trodden was killed, it also had dire, though not fatal, consequences for Lizzie Lowe.

She was the Cumann na mBan member tasked with bringing the dead policeman’s rifle three miles over Black Mountain to an IRA arms dump in Hannahstown.

Constable Thomas Leonard, killed by the IRA on 25 September 1920

Along the way, she was soaked in the rain: “…as a result of that night, I took a pleurisy and was hovering between life and death for a week.”46

This marked the beginning of her decades-long battle with both sickness and the Department of Defence.

The following January, she was diagnosed as suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis by the Central Tuberculosis Institute in Durham St and was still being seen by them on an out-patient basis 15 years later; the former Medical Officer of the IRA’s 1st Battalion, Dr James Ryan, also certified that she was suffering from the disease.47

She had asked the doctor who was her GP throughout the 1920s for a supporting statement but he, being a unionist, had refused:

“In July last, I approached Dr Turnbull for a certificate regarding my illness and he queried me as to why I wanted same, of course I had to tell him and when I did so he got very angry and said ‘Let the Free State Pensions Board solve their own difficulties, they will get no assistance from me.’”48

The former Central Tuberculosis Institute, Durham St, where Lizzie Lowe was treated

The Army Pensions Board wanted more proof and paid for her to travel to Dublin in July 1937, where she was examined in St Bricin’s Hospital by Professor Henry Moore; he told them, “I could find no evidence whatsoever of pulmonary tuberculosis.” As a result, she was told six weeks later that her claim had been rejected: “You are not suffering from any disability attributable to service.”49

A new avenue of approach opened up for her when the Chief Tuberculosis Officer for Belfast examined her at the end of September and found she was suffering asthenia and general debility, following pulmonary tuberculosis. Following a personal appeal by Joe Cullen, secretary of the Belfast Brigade Committee, the Army Pensions Board invited Lizzie to submit a new claim under the 1937 Act for disability arising from these conditions.50

In January 1938, she did so, stating that, “I have been unemployed for long periods owing to the state of my health. I am not now fit for any work.” Given that the department had specifically asked her to submit a new application, Lizzie should have had grounds to feel optimistic about receiving a more favourable response the second time around.51

These hopes did not last long – within six months, her second application was rejected on exactly the same basis as her first: “There is no evidence that you contracted the disease in respect of which you are now claiming, viz. asthenia and general debility, during your military service.”52

In September 1946, she and her sister applied for 1917-1921 Service Medals; Lizzie’s was issued to her the following January – there had never been any question regarding her membership of Cumann na mBan, in fact, their house in Cawnpore St in Clonard had been used as the headquarters and arms dump for B Company, 1st Battalion throughout the Pogrom.

However, she used the granting of the medal as the basis for launching a third attempt to loosen the purse-strings of the department: “Would you kindly forward two claim forms under the new scheme whereby the Govt. are granting assistance to destitute or disabled persons who were awarded the Military Service Medal.”53

Despite her age – she was now 70 years old – she was working part-time to support her sister, earning £80 a year on top of her old age pension of £66/12/-: “Though I am unfit for work circumstances compel me to work to maintain our home as our old age pensions are insufficient but I will gladly avail of the opportunity to cease work to attend to my invalid sister if an allowance is granted to me.”54

Lizzie may have been destitute, but she wasn’t destitute enough – incredibly, her third application was also turned down: “Your yearly means exceed the appropriate annual sum which in your case is £78 per annum.”55

Bernard Mullen was severely wounded when attempting to attack a Special Constabulary armoured car on 26 March 1922

Bernard Mullen received severe wounds in the course of a battle with Special Constabulary in the Lower Falls on 26 March 1922 – another IRA member, James Magee, was killed in the same incident and four others, including the Brigade Quartermaster Joseph Savage and the 1st Battalion O/C Tommy Flynn, were arrested later that night in a raid on Flynn’s house.56

According to Bernard:

“I was asked by my company Captain to repulse an attack on a Catholic area by armoured cars, the occupants of said cars being Crown Forces, I my self being armed with bomb + revolver, went to attack first car, I didn’t see a second car coming around side street, which opened upon me with machine gun fire. The said firing was cause of a wound in the neck, 5 teeth lost, 5 bullets in right leg and loss of right hand.”57

As he was falling to the ground, the bomb he had intended throwing had exploded, shattering his hand. After being rescued from the Mater Hospital by the IRA, Bernard was brought south for medical treatment, where his arm was amputated above the wrist. In November 1923, he lodged a disability claim under the 1923 Act and although this was approved in July 1924 with the award of a disability pension of £1/11/6 (one pound, eleven shillings and six pence) a week, that was by no means the end of his dealings with the Department of Defence.58

Along with his pension, the department had sanctioned the supply of two artificial hands to him. In May 1929, he wrote to them,

“… only received one to date 10th Sept 1924 … the hand i was using is long past its best … could i receive the spare hand that was allotted to me … at the present i am wearing an old hand held on by two bits of brace + uncomfortable is no name for it”.59

The replacement hand was not supplied until 1932. By 1937, it was also worn out and the Belfast Brigade Committee had to intervene to ask the department to speed up the supply of a new one.60

Bernard asked for another new artificial hand in 1943 but this time, the Army Pensions Board asked a prosthetics supplier in Belfast to quote for repairs to the existing one; Bernard was asked to bring it to them for assessment but was unable to do so – he claimed the police had stolen it: “I myself have been arrested twice. Detained under S/P/A [Special Powers Act]. So you can see I am not responsible for anything that goes amiss through these raids.” A replacement hand was provided to him later that year.61

Like many others who were wounded or disabled, Bernard’s employment prospects were drastically affected in the aftermath of the Pogrom. Prior to being wounded, he had worked as a wood turner, earning £4/5/- a week, but he never worked again after his hand was amputated: “I had no chance of work here or never had. Nobody wants a broken reed.”62

Compared to either Lizzie Lowe or Bernard Mullen, Rose Black arguably paid an even heavier physical price in later years for her Cumann na mBan activism.

She applied for a certificate of military service and its accompanying pension in December 1935. According to the stellar reference supporting her application, signed by six former 3rd Northern Division officers, she did not take part in normal Cumann na mBan activities, but instead was the custodian of Belfast Brigade money and made regular trips to Dublin, bringing gold and money to Headquarters and buying weapons and ammunition which she brought back to Belfast.63

Her house was raided in June 1921 and she was arrested when the money, some gold and documents were found; on 26 July 1921, she was tried by a Field General Court Martial and sentenced to five years in jail. She was released from Armagh Gaol under the Truce in September 1921 and went on the run, resuming her former activities; she remained at large until she was once more arrested and interned in February 1923.64

Given the strength of her references, she was granted a pension of £22/10/- a year in December 1941.65

However, in the interim since her original application, she had lodged a parallel application for a disability pension. This application was initiated on her behalf by a friend, Elizabeth Brady, as imprisonment and interment had taken a terrible toll on Rose: “…except for ability to distinguish between daylight and darkness she is completely blind.”66

Armagh Gaol, where Rose Black was imprisoned and later interned

Her problems had begun when she was first sent to Armagh Gaol:

“My left eye was weak from childhood, but my right eye was perfect. If right eye was closed – I could not see with left – only light … I was imprisoned in Armagh. I could not even sleep. My right eye was going misty. My eyes were examined by Dr Palmer. I was released in October 1921. My right eye was weak on being released, but after a while it got better.”67

The problem returned after she was interned:

“I was on partial hunger strike for 8 weeks, with a view to so weakening myself that I would be released. My right eye got bad again. I was in bed for about a month owing to weakness. I had got to the point where I was not able to eat. On release I was brought by a prison nurse to my own home.”68

After her release on medical grounds in July 1923, she went to Dublin, where she was prescribed glasses. However, her visual problems returned the following January; after treatment in the Eye & Ear Hospital in Belfast, her right eye recovered, but that recovery only lasted three years:

“My right eye got well and continued well until 1927. Mr Hanna, Royal Hospital, treated me for about a year. This was in 1928. He operated on me in February, 1929, and I was in hospital for 6 weeks. My eye began getting darker after the operation – 1930 and it has been dark since.”69

Unlike Lizzie Lowe, the Army Pensions Board were unable to controvert the overwhelming medical evidence regarding Rose – even their own doctor agreed that she was totally blind and 100% disabled. In February 1940, she was granted a disability pension of £100 a year.70

The following month, in order to facilitate payment of this pension, she was asked to provide a specimen of her signature. Up to now, all written correspondence in connection with her applications had been signed by others on her behalf. But now, at the age of 63, she made one last attempt to write her own name. It is heart-breaking to read. Clearly unable to see either pen or paper, she must have moved her hand across the page purely from memory. The end result resembles nothing so much as the failed attempt of a small child trying to tackle joined-up writing for the first time.71

“I suppose I am just one of Ireland’s fools”

As well as the Army Pensions Acts, which provided for payments in respect of deaths, wounds and disabilities, there was also a series of Military Service Pensions Acts, under which veterans could claim pensions in respect of the activities in which they had been involved.

A critical issue confronting both applicants and those in charge of administering the process was that there was no legal definition of what constituted “military service:”

“Those charged with assessing the claims of pension applicants were forced to make their own definitions of both legitimate veterans and recognizable service as none of the legislation or regulations ever defined the terms satisfactorily. The 1924 legislation defined military service merely as ‘active service in any rank’ in the eligible forces. This was changed in 1934 to the equally vague ‘rendering active service.’”72

In practice, establishing an applicant’s membership of one of the qualifying organisations and the extent of the service they had rendered was usually done by referring to officers from the unit in question: in theory, they would be able to verify the claims made by applicants.

However, this did not prevent applications being rejected on grounds that veterans found perplexing, frustrating or insulting.

A case in point is that of Bernard Mullen. In July 1936, while in receipt of the disability pension in respect of his amputated hand, he applied for a military service pension, only to be eventually told in June 1941, in the dry, legalistic phrase that was routinely used: “you are not a person to whom the Act applies.” In effect, despite being grievously wounded while throwing a bomb at a Special Constabulary armoured car, this did not count as “active service.”73

Bernard continued to fight a curious, seemingly contradictory battle with the department, having an appeal against the pension decision rejected, yet successfully applying for a 1917-21 Service Medal in 1945. After the latter, he wrote to the department, arguing: “About 12 months ago I received a Service Medal and Ribbon. If I am eligible for one of these prized medals, why not a pension?”74

A 1917-21 Service Medal

However, qualification for a medal was more straightforward than the byzantine requirements needed to qualify for a pension – all that was needed for the former was to be able to demonstrate membership of one of the republican organisations in the three months prior to the Truce. But given the similarity in terminology, the distinction between qualifying for a Service Medal and qualifying for a service pension was probably lost on many applicants.

Having passed the closing date for further appeals, Bernard then applied in September 1947 for a Special Allowance, similar to that which Lizzie Lowe had applied for, but this was also rejected as, “Your yearly means exceed the appropriate annual sum, which in your case is £118/6/-.” An appeal against that decision was heard in Dundalk, but in circumstances which further infuriated him: “Whilst on the subject of the interview I would like to state that this particular one was in the nature of an insult. A 5 minute chat in a draughty railway station seems to be the cause of my application being rejected.”75

He made one last attempt, applying for a married pension in April 1954. Finally, in January 1955, the MSRB concluded that he had, after all, been a member of the IRA and had engaged in military service, so they recommended payment of the pension. Only one formality remained – on 27 January 1955, the department wrote to him, requesting a copy of his wife’s death certificate. But Bernard himself had died on 18 January.76

Some veterans were deeply hurt by the rejection of their claim for military service as it seemed a negation of all their previous efforts. After being told “you are not a person to whom the Act applies”, Daniel Megran wrote:

“I want nothing from you only what a Simple Soldier is entitled to from a Grateful Country. I have been telling many a time my family of our Exploits and instilling in them that love for my country which is the duty of any Irishman. But now your disqualification has made me out to be a Liar and Cheat, that I am almost ashamed to speak of Irish aspirations and Unity.”77

His appeal against the decision was also turned down, prompting him to respond, “…the Irish Government says you are not a fit and Proper Person to hold a Certificate. In other word it was only in your imagination you fought in Pre Truce Days for Irish IRELAND.”78

The Military Service Pensions (Amendment) Act 1949 made provision for unsuccessful applicants to request a re-investigation of previous claims, so in 1950, Daniel applied for a review of his case; as part of this process, he was interviewed, but that interview only served to further antagonise him:

“What annoyed me more than anything else was at the referee who I believe was a Mr Maguire Civil Servant telling me that our FIGHT here in the NORTH was only a Religious Fight and that we never came into contact with Enemy Forces … I can tell you I was heartily sick at such a statement Religious Fight when all I had done was for my COUNTRY … All I Ask is for Justice”79

Although, like Bernard Mullen, he was granted a 1917-21 Service Medal, the department remained unmoved in relation to a pension.

Edward McCready applied for a military service pension in February 1935. Among the operations which he said he had taken part in were the burning of seven business premises in Belfast during the IRA’s arson campaign of May-June 1922; in one of these attacks, he sustained third degree burns to his hair, face, neck, arms and hands, which put him in hospital for six weeks.80

Doran & Co.’s bonded spirits warehouse, the target of an IRA arson attack on 19 May 1922; Edward McCready said he took part in the attack

His claim was rejected in September 1940 on the grounds that “you are not a person to whom the Act applies.” He did not take the rejection well: “If I had served Britain as well as I did Ireland she at least does not forget her living but Ireland seems to thrive on her dead.”81

In 1945, he applied for a 1917-21 Service Medal. From the ensuing correspondence, it is clear that he was still seething – among the targets of his ire were the former 3rd Northern Division officers who had gone on to forge careers in the Free State Army and the Defence Forces after leaving Belfast: “The men I worked under got to be such big fellows in the mad scramble that followed when they went to Dublin they forgot the fellows that put them there … I suppose I am just one of Ireland’s fools.” At the third time of asking, his medal was finally awarded in February 1950.82

While his medal applications were being processed, he also applied, under the terms of the 1949 Act, for a review of the finding in his original pension application. However, in June 1955, he was told that he was still not a person to whom the Act applied.83

In 1968, by now aged 68, Edward made a final attempt to get some financial aid from the department when he applied to them for free travel. However, this application was to backfire on him. A reference was sought from Séamus Nolan, who had been a Lieutenant in D Company, 2nd Battalion, to which Edward had belonged; Nolan’s response was damning: “I knew the applicant since school days and never knew he had a connection with IRA.”84

When writing to Edward to inform him of the rejection of this application, the department added insult to injury:

“It has not been established that you were a member of Óglaigh na hÉireann (IRA) continuously during the three months which ended on 11 Iúil [July] 1921. The Medal issued to you cannot, therefore, be held to have been duly awarded. It is regretted that, under the circumstances, you are not eligible for the free travel, etc concessions which are being made available to Veterans of the War of Independence.”85

Although he did not ask Edward to return the unduly-awarded medal, the anonymous civil servant need not have bothered, as Edward’s file contains an interesting postscript. In 1988, his daughter wrote to the department from Australia, requesting a replacement medal – according to her, he had “Returned it to Seán T. O’Kelly (president) some time in 1966, when he failed to receive a pension.”86

While it would be tempting to view this action as being linked to the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, it is more likely that she got the date wrong – O’Kelly’s term of office as President ended in 1959. Having fought for his country, suffered terrible injuries as a result and had two pension applications turned down, the most recent in 1955, Edward must have decided not long after the second rejection that he didn’t want the medal after all.

Summary and conclusions

So far, the Military Service Pensions Collection files of 221 people have been released which relate to the events in Belfast between 1920-22; these include members of the IRA, Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna, as well as civilians.

Some people applied for both a service pension and a disability pension and got both, like Rose Black. Some applied for both, but were denied a service pension though granted a disability pension, like Bernard Mullen. John Donegan applied for both and got neither. Patrick Taylor applied twice for a service pension, once under the Military Service Pensions Act 1924 and again under the 1934 Act, but was turned down twice.87

Each application involved submitting to a glacially slow assessment process. The apparatus for dealing with claims was clearly understaffed and overwhelmed by the sheer volume of applications, prompting Belfast IRA veteran Davy Mathews to howl, “Is the comm[ittee] going to be so slow in dealing with the many cases … that all claimants will go to the great beyond to await a pension.”88

In total, 154 applications were successful, roughly 70%. For the most part, these successful applicants had no choice but to accept whatever payments they were given, as the levels of awards for pensions, allowances and gratuities were strictly defined by the relevant legislation. In many cases, the gratuities paid by the Free State were less than the grants previously made by the Irish White Cross to the same applicants. In many cases, they were even less than the frugal awards made under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts in the north and yet the Department of Finance was still apt to quibble with what they viewed as unseemly generosity on the part of the Department of Defence. Eventually, the successful applicants just disappeared quietly into the twilight.89

Partition was a key defining feature of that twilight and those who had survived the Pogrom still had to contend with the day-to-day discrimination at the hands of the authorities suffered by nationalists of whatever shade – police raids as in the case of the Troddens, or being arrested like Bernard Mullen. That aspect of life under partition was summed up by Davy Mathews: “Being a married man with nine of a family and due to my political convictions, I have and am still being victimised, at present out of work and receiving no dole.”90

His reference to the dole highlights another feature of life after the Pogrom. With the post-Great War downturn in the economy, high levels of unemployment were already endemic in Northern Ireland in the 1920s, even before the arrival of the Great Depression. Applicants were driven by sheer need to turn their hopeful faces to Dublin in supplication, looking for a measure of relief from the grime and grind of their everyday lives; the prospect of at least some level of financial support offered a chance to partially alleviate their gruelling poverty.

So acute was their hunger that it is mainly in the correspondence of unsuccessful applicants that the miserable economic and social conditions which they had to navigate can be seen – they were the ones who, terrified of the consequences of their claims being rejected, pleaded the most: “its only workhouse for me now,” or “I have only 6/- disablement benefit to live on.”

Among the 67 unsuccessful applicants, some notable clusters can be seen.

There were 38 rejected applications for military service pensions, mainly due to pre-Truce or National Army service not being recognised for claims under the 1924 Act or the all-encompassing “you are not a person to whom the Act applies” dismissals of later applications.

Fourteen unsuccessful applications were made by dependents of those killed – nine of these related to civilians, who were not covered by the legislation, and five related to IRA or Fianna members, but were debarred by having already been compensated under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts.

Eight claims were lodged by dependents of veterans who died after the Pogrom, but the medical conditions that led to their deaths were deemed not to have been due to military service. Some of these decisions seem baffling: just like John O’Donnell, Daniel Dempsey was arrested and interned on the Argenta and died from tuberculosis, but unlike O’Donnell who died in 1925, he did not die until 1935. So, in his case, “not due to service” could be read either as “contracted it later” or, more harshly, as “it didn’t kill him quickly enough.”91

In the case of Lizzie Lowe, tuberculosis didn’t kill her at all but she still had to endure it and its after-effects for the rest of her life. Rose Black never saw again for the rest of her life. Bernard Mullen had to go through the rest of his life with only one hand. Robert Copeland had to go through the rest of his life with shrapnel in his leg, the result of a bomb being thrown by Special Constabulary in Seaforde St, Ballymacarrett in March 1922. As late as 1970, he was still waging a futile effort to persuade the department to grant him a disability pension and was still incandescent in his rage at being refused:

“When the time comes my time, will you have to add another name to your books of those who were in want but you turned down … Many of these veterans would be much better off today if they had devoted their youth to furthering their own welfare instead of risking their lives to win freedom for an ungrateful people … if general Collins were alive to day i dought if he would be pleased in the way the members of An Taire Cosanta [Department of Defence] considered my case, he stood for no nonsense.”92

Whether their claims were successful or not, these broken veterans had to carry their wounds or disabilities for the remainder of their lifetimes.

Those left bereaved by the killings of family members had to carry that loss for the remainder of their lifetimes. For some, like the father of Alexander Hamilton or the husband of Annie McNamara, the burden was simply intolerable and they soon “died from a broken heart.” Catherine McGovern had the added pain of being goaded by gloating loyalists, revelling in the killing of her brother; she was unlikely to have been unique in that regard.

For all of them, whether their claims were successful or not, whether their applications were stymied or not by payments under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts, apart from the loss of a loved one, they also had to face into the permanent loss of a key, if not only, breadwinner’s earnings.

Those who failed to have their military service recognised at all were understandably bitter, as it implied that a fraught, extremely violent period of their lives had not really happened, even though they remembered it vividly – “it was only in your imagination you fought.” Their erstwhile comrades in the south had fought and won some measure of independence, but they had fought and won nothing, so being written out of the officially-recognised history of the entire fight must have compounded their feelings of having been abandoned by the south.

The apparently contradictory award of Service Medals but denial of service pensions can only have deepened their frustration. Were these “prized medals” actually just worthless baubles, scattered about with abandon, or did they carry a hidden implicit criticism – that while the recipients whose pension claims were rejected had been members of the IRA, they hadn’t actually done anything of merit?

No wonder that Edward McCready decided that he wanted nothing more to do with a country that would give him a medal but not a bus pass.

References

1 This publication can be accessed at: https://www.militaryarchives.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/36_MSPC_Hard_Struggle_online_2Nov_WEB_VERSION.pdf

2 Elizabeth Trodden to Minister for Defence, 10 June 1924, Military Archives (MA), Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), 1D153 Edward Trodden. The punctuation, spelling and grammar of letters sent by applicants have been left unchanged from the originals.

3 Ibid.

4 Army Pensions Act, 1923 https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1923/act/26/enacted/en/html

5 Lia Brazil & Melanie Oppenheimer, ‘Saving “Ireland’s children”: voluntary action, gender, humanitarianism, and the Irish White Cross, 1921–1947,’ in Women’s History Review, Volume 31 Issue 7, 2022, pp1169-1189; John Ó Néill, The Irish White Cross, https://treasonfelony.wordpress.com/2021/12/04/the-irish-white-cross-2/

6 Elizabeth Trodden to Minister for Defence, 4 September 1924, MA, MSPC, 1D153 Edward Trodden. Compensation awards made by the Belfast Claims Court were sometimes accompanied by an additional grant towards funeral expenses – this may have been the £50 to which she referred.

7 Ministry of Defence to Elizabeth Trodden, 1 December 1924, ibid.

8 (British military service) Belfast Telegraph, 13 July 1921 & Northern Whig, 3 June 1922; (killing) Irish News, 11 July 1921; at the subsequent inquest into his death, it emerged he had actually been killed in nearby Cupar St, Belfast Telegraph, 9 August 1921.

9 Mary Ann Hamilton application form, 28 November 1923, MA, MSPC, 1D47 Alexander Hamilton; Northern Whig, 3 June 1922; Ministry of Defence to Mary Ann Hamilton, 17 January 1924, MA, MSPC, 1D47 Alexander Hamilton.

10 Department of Defence to Mary Ann Hamilton, 24 November 1932, ibid.

11 Jack McCusker to Department of Defence, 22 September 1936, ibid.

12 Mary Ann Hamilton to Department of Defence, 12 August 1937, ibid.

13 Department of Defence to Jane Moan, 21 August 1935, MA, MSPC, DP3403 Owen Moan.

14 William Morrison to Military Service Registration Board (MSRP), 9 September 1939, MA, MSPC, DP3403 Owen Moan (2RB4209).

15 Desmond Crean interview with Advisory Committee, 4 November 1939, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF4970 Desmond Crean.

16 Department of Defence to Jane Moan, 20 April 1940, MA, MSPC, DP3403 Owen Moan.

17 Department of Defence to Fr John Nugent, n.d. December 1934, MA, MSPC, 1D446 John Walker.

18 Department of Defence to Ellen Walker, 14 November 1934, ibid.

19 Department of Defence to Ellen Walker, 9 July 1941, MA, MSPC, 1D446 John Walker (WY413).

20 Secretary, St Vincent de Paul Society to Army Pensions Department, n.d. 1924, MA, MSPC, 1D325 James Ledlie.

21 Hugh Ledlie to W.T. Cosgrave, 10 September 1929, ibid.

22 Ministry of Defence to Hugh Ledlie, 24 September 1929, ibid.

23 Catherine McGovern to Department of Defence, n.d. December 1932, MA, MSPC, DP7608 Francis McCann.

24 Catherine McGovern to Department of Defence, 28 December 1932, ibid.

25 Thomas McNamara to Department of Defence, 2 February 1933, MA, MSPC, DP8309 Annie McNamara.

26 Ibid.

27 Mary Ann Lynch to Department of Defence, n.d. September 1932, MA, MSPC, DP8582 Robert Lynch.

28 Mary Ann Lynch to Department of Defence, n.d. October 1932, ibid.

29 Patrick McCarragher to MSRP, 3 May 1939, MA, MSPC, DP8582 Robert Lynch (2RB4017).

30 Department of Defence to Mary Ann Lynch, 25 April 1939, MA, MSPC, DP8582 Robert Lynch.

31 Elizabeth Burns to Department of Defence, n.d. June 1933, MA, MSPC, DP931 Welhemina Burns; Belfast News-Letter, 15 June 1921.

32 Department of Defence to Elizabeth Burns, 21 November 1934, MA, MSPC, DP931 Welhemina Burns.

33 Thomas Rogan to Minister for Defence, 5 July 1932, MA, MSPC, DP6381 Daniel Rogan.

34 Northern Whig, 4 April 1922; Certified Copy of Entry in the Register Book of Deaths, 8 February 1933, MA, MSPC, DP6381 Daniel Rogan.

35 Thomas Rogan application form, 9 July 1933, ibid.; Belfast News-Letter, 1 November 1922.

36 Joseph Cullen to MSRP, n.d., MA, MSPC, DP6381 Daniel Rogan (2RB463).

37 Brigid O’Donnell to Minister for Defence, 10 August 1932, MA, MSPC, DP1178 John O’Donnell.

38 Brigid O’Donnell application form, 3 February 1933, ibid.

39 MA, MSPC, 24SP12908 Henry Russell MacNabb; Statement by Dr H. Russell MacNabb, 10 January 1933, MA, MSPC, DP1178 John O’Donnell.

40 Fr John McKee to Army Pensions Board, 29 August 1933, ibid.

41 Record card, n.d., MA, MSPC, DP1178 John O’Donnell (2RB77).

42 Mary Josephine Hennon to Department of Defence, 9 February 1933, MA, MSPC, DP4364 Hugh Hennon.

43 Statement of Dr Bradley, 10 March 1933, ibid.

44 Mary Josephine Hennon application form, 11 March 1933, ibid.

45 Army Pensions Board to Minister for Defence, 15 November 1933, ibid.; Department of Finance to Department of Defence, 7 April 1934, ibid.; Department of Finance to Department of Defence, 22 October 1934, MA, MSPC, DP4364 Hugh Hennon (Y183).

46 Lizzie Lowe to Department of Defence, n.d. May 1933, MA, MSPC, DP5454 Elizabeth Lowe.

47 Central Tuberculosis Institute statement, 8 August 1936, ibid.; Dr James Ryan statement, 17 May 1933, ibid.

48 Elizabeth Lowe to MSRP, 2 October 1936, MA, MSPC, DP5454 Elizabeth Lowe (1RB4611).

49 Professor Henry Moore to Army Pensions Board, 23 July 1937, MA, MSPC, DP5454 Elizabeth Lowe; Department of Defence to Elizabeth Lowe, 6 September 1937, ibid.

50 Chief Tuberculosis Officer to Dr James Ryan, 24 September 1937, ibid.; Jospeh Cullen to Army Pensions Board, 14 October 1937, ibid.; Department of Defence to Elizabeth Lowe, n.d., ibid.

51 Elizabeth Lowe application form, 22 January 1938, ibid.

52 Department of Defence to Elizabeth Lowe, 29 June 1938, ibid.

53 Elizabeth and Rose Ann Lowe to Department of Defence, 23 October 1947, ibid.

54 Elizabeth Lowe application for Special Allowance, 10 November 1947, ibid.

55 Department of Defence to Elizabeth Lowe, 11 February 1948, ibid.

56 MA, MSPC, 1D213 James Magee; Belfast News-Letter, 27 & 28 March 1922.

57 Bernard Mullen to Department of Defence, 24 June 1923, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (1P17).

58 Certificate of Assessment, 12 August 1924, ibid.

59 Bernard Mullen to Army Pensions Board, 7 May 1929, ibid.

60 Bernard Mullen to Army Pensions Board, 24 November 1943, ibid.; Belfast Brigade Pensions Committee to Army Pensions Board, 27 September 1937, ibid.

61 Bernard Mullen to Army Pensions Board, 20 January 1944, ibid.

62 Bernard Mullen application to Compensation (Personal Injuries) Committee, 11 May 1923, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (W653-174); Bernard Mullen to Department of Defence, 22 November 1940, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen.

63 Brigade Pensions Committee to Army Pensions Board, 1 March 1938, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF22470 Rose Black.

64 Statement of Patrick Fox and Joseph Cullen to Advisory Committee, 15 June 1938, ibid.

65 Department of Defence to Rose Black, 15 December 1941, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF22470 Rose Black (34E5657).

66 Elizabeth Brady to Department of Defence, 11 December 1932, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF22470 Rose Black (DP1053).

67 Statement of Rose Black, 22 February 1939, ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Department of Defence file note, 16 February 1940, ibid.

71 Rose Black to Department of Defence, 13 March 1940, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF22470 Rose Black (V680).

72 Marie Coleman, ‘Military service pensions and the recognition and reintegration of guerrilla fighters after the Irish revolution,’ in Historical Research, volume 91, no. 253 (August 2018), pp554-572.

73 Bernard Mullen application form, 15 July 1936, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen; Department of Defence to Bernard Mullen, 11 June 1941, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (34SP24455).

74 Bernard Mullen to Department of Defence, 5 September 1945, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (1P17); Bernard Mullen to Department of Defence, 13 November 1946, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (34SP24455).

75 Department of Defence to Bernard Mullen, 8 December 1947, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF31128 Bernard Mullen (1P17); Bernard Mullen to Department of Defence, 17 December 1947, ibid.

76 Bernard Mullen application form, 2 April 1954, ibid.; MSRB Certificate, 20 January 1955; Department of Defence to Bernard Mullen, 27 January 1955, ibid; Certified Copy of Entry in the Register Book of Deaths, 19 January 1955, ibid.

77 Daniel Megran to Department of Defence, 26 June 1940, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF11032 Daniel Megran.

78 Daniel Megran to Department of Defence, 24 March 1942, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF11032 Daniel Megran (34SP10734).

79 Daniel Megran to Department of Defence, 2 December 1950, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF11032 Daniel Megran.

80 Edward McCready application form, 23 February 1935, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF10759 Edward McCready; Dr Russell MacNabb certificate, 13 February 1933, ibid.

81 Department of Defence to Edward McCready, 27 September 1940, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF10759 Edward McCready (34SP10776); Edward McCready to Department of Defence, n.d., ibid.

82 Edward McCready to Department of Defence, 1 October 1945, ibid.

83 Department of Defence to Edward McCready, 6 June 1955, ibid. One of the factors that impeded his various claims was the fact that his name was not included in the nominal roll of members of D Company, 2nd Battalion (3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast), 2nd Battalion, MA, MSPC, RO/404). This was probably the most problematic of the generally problematic Belfast nominal rolls – on the “first critical date”, 11 July 1921, it was shown as having only 22 members, nine of whom gave the same care-of convenience address in a different part of the city; other companies in the same battalion had between 82-110 members on that date. However, as was noted in respect of a different company in Belfast, “…there are men who will not allow their names to appear on this list, owing to the nature of their employment.” M. McManus to Department of Defence, 7 January 1937, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast), 4th Battalion, MA, MSPC, RO/406.

84 Séamus Nolan to Department of Defence, 28 September 1968, ibid.

85 Department of Defence to Edward McCready, 16 November 1968, ibid.

86 Kathleen Begg to Department of Defence, n.d. June? 1988, ibid.

87 MA, MSPC, MSP34REF57409 & DP706 John Donegan; MA, MSPC, 24SP10123 & MSP34REF25758 Patrick Taylor.

88 David Mathews to Department of Defence, 21 November 1933, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF60258 David Matthews (1RB1254).

89 The most notable exception was Winifred Carney, who successfully argued that her pension should be paid at an officer’s level, in view of the fact that she had been James Connolly’s Aide-de-Camp during the Easter Rising. MA, MSPC, MSP34REF56077 Winifred Carney.

90 David Mathews to Department of Defence, 18 January 1933, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF60258 David Matthews (DP3040).

91 MA, MSPC, DP9279, Daniel Dempsey. IRA member Robert O’Kane died from pneumonia and cardiac failure during the Pogrom, in August 1921, but these were also deemed “not attributable to your son’s service in the Irish Volunteers.” Department of Defence to Mary O’Kane, 13 February 1930, MA, MSPC, 1D480 Robert O’Kane.

92 Robert Copeland to Department of Defence, n.d. September 1970, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF8434 Robert Copeland (5P93). He wrote this letter in response to being told – for the eighth time – that his disability claim was ineligible as his father had been awarded compensation for his wounds under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Acts.

Leave a comment