Estimated reading time: 30 minutes.

For clarity, readers should bear in mind that £1 in 1920 would be worth £61.36 today. For the benefit of those too young to recall pre-decimalisation, there were 20 shillings in a pound and 12 pennies in a shilling.1

Establishment of the Loyalist Relief Fund

The Belfast Pogrom began with the violent expulsion of Catholics and “rotten Prods” – socialists and trade unionists – from their jobs in the shipyards on 21st July 1920. Over the following days, these attacks spread to other large industrial workplaces in the city.

A week later, on 28th July, an Expelled Workers Relief Committee (EWRC) was formed at a meeting in St Mary’s Hall, initially led by James Baird and John Hanna, who had been on the strike committee of the huge 1919 engineering strike in Belfast and were therefore numbered among the “rotten Prods.” The EWRC launched a Relief Fund in mid-August, with an appeal signed by expelled trade unionists, Belfast Labour Party figures, Catholic clergy and representatives of the Society of St Vincent de Paul.2

“Most of the assistance given the expelled workers came from local Catholic agencies, Sinn Féin sources, and, from 1921, the White Cross … In Britain, the EWRC operated through the Labour movement and Irish organisations like the United Irish League, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Irish Self-Determination League. The EWRC also lobbied in the United States, Canada, Australia, France, Spain and Belgium.”3

Letter supporting the Expelled Workers Relief Fund (National Library of Ireland, ILB p300 p11)

By the following December, when a visiting delegation from the British Trades Union Congress observed the EWRC’s operations at St Mary’s Hall, there were 9,000 unemployed workers registered to receive relief: married men got £1 a week, unmarried men got 10/- (shillings). They were also entitled to unemployment benefit from their trade unions or the state but “…the total, in the best of cases, would fall materially short of what even an unskilled workman might receive in the shipyards.”4

At the end of September, the establishment of a countervailing Loyalist Relief Fund was announced in the unionist press in Belfast; this was a joint venture of the Ulster Unionist Council and the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA). The method chosen to make the announcement was to publish a letter from Sir Edward Carson, the leader of unionist opposition to Home Rule before the Great War, in which he claimed that loyalists had also been subjected to workplace expulsions as well as evictions:

“Dear Sirs, l send you a contribution of £5O towards the Fund which has been opened in Belfast to alleviate the distress caused by the treatment of loyal citizens who have been driven from their homes or their work for no other reason except that they were loyal subjects of the Crown and refused to be parties to the cowardly policy of disorder and outrage which is at present rampant in Ireland.”5

In relation to evictions, Carson was correct – unionists were put out of their homes as well as nationalists: Robert Lynch has stated that over the course of the Pogrom, 10,000 people were forced to move within Belfast – 8,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants.6

A family – it is obviously impossible to tell their religion – fleeing from their Grosvenor Road home (Illustrated London News, 4th September 1920). In 1911, the population of the Grosvenor Road was 85% Protestant, 15% Catholic.7

However, in relation to expulsions from workplaces, Carson was – at best – being disingenuous. While it is very likely that some unionists were forced from small-scale places of employment, any such incidents are undocumented and would not have been of the same magnitude as those which began the Pogrom.

An attempt to put more substance on Carson’s claim was made the following month at a ceremony held to unveil a giant Union Jack in Harland & Wolff. The meeting was addressed by Sir James Craig and by John F. Gordon, an honorary secretary of both the UULA, which had been instrumental in the shipyard expulsions, and the Loyalist Relief Fund; Gordon said:

“’Loyalists cannot walk on their way without molestation, and the hitherto tolerant people of the shipyards determined that if their fellow-workers were not permitted to work in the shipyard in Londonderry, Sinn Feiners would not be permitted to work with Unionists and Loyalists in Belfast.’ … In regard to the Loyalist Relief Fund which they had inaugurated, they were determined to their very best to ameliorate the conditions of the loyal workers and to assist those who had been thrown out of employment.”8

Here, Gordon was repeating rumours which had circulated relating to intimidation of unionists working in the Foyle Shipyard in Derry in retaliation for the expulsions in Belfast – apparently, those being targeted in Derry had received anonymous typewritten warnings telling them to get out of the city. The nationalist Derry Journal investigated and perhaps unsurprisingly, given its political leaning, found that the letters were a hoax: “…the document is part of the miserable game being carried on for the purpose of misrepresenting not only Sinn Fein but all friends of the National movement.” 9

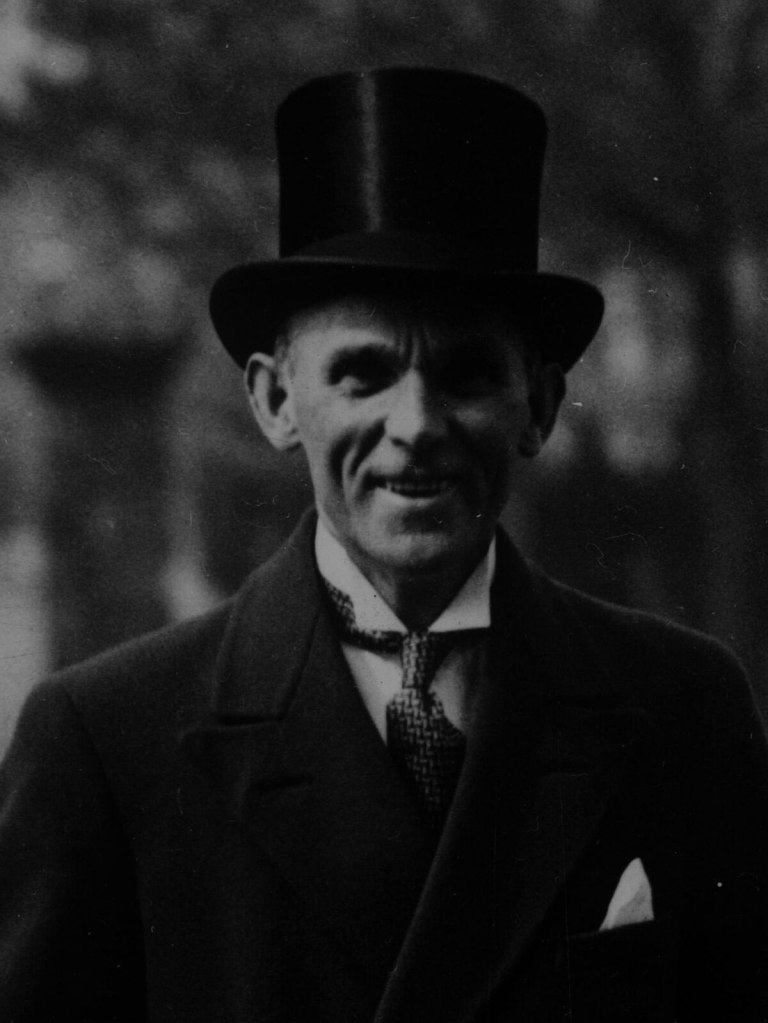

John F. Gordon of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association, pictured in the 1940s

But more strikingly, neither the unionist Londonderry Sentinel nor the Belfast unionist newspapers made any references to such attempted expulsions of Derry unionists.

Another of the leading figures in the Loyalist Relief Fund was William Grant. Like Gordon, Grant was centrally involved in the UULA, having been one of its founding members in 1918. He worked in the shipyard and “Undoubtedly, his work environment influenced his politics which were staunchly unionist, sectarian (he was also a member of the Orange Order), and working class.” Grant was wounded by a sniper in July 1921, shortly after being elected as a UULA MP in the Parliament of Northern Ireland, where he declared that, “‘If the Sinn Feiners would not come under the law they would have to take steps to expel them from the six counties.’”10

Grant was not averse to taking a hands-on approach to the expulsion of “Sinn Feiners,” on one occasion leading 5,000 of his constituents, abetted by the Ulster Special Constabulary, on a rampage against nationalists on York St where, according to a police Sergeant, “They smashed the furniture, looted the houses and robbed numbers of people. The mob helped them to wreck and loot. Amongst the mob that day was the local member Grant M.P. who led the looters and wreckers.”11

In a supremely ironic move, in the following year, Grant was appointed to the Commission of the Peace for Belfast.12

William Grant later became a member of the Unionist Government of Northern Ireland

Fundraising

The initial response to the Fund was somewhat lacklustre, so in January 1921, the unionist press weighed in and began running weekly exhortations to their readers to contribute. These notices were prominently positioned next to the editorial columns and also listed those who had contributed and how much: “There appears to-day in our advertising columns a list of subscriptions to the Loyalist Relief Fund organised for the alleviation of the distress caused among Loyalist workmen and their dependents in consequence of the riots of last summer.”13

When the Northern Whig published this on 19th January, the cumulative total of donations to the Fund stood at £1,580, the equivalent of almost £90,000 today. The largest single donation had come from the Belfast Telegraph, which gave £100; the Belfast News-Letter had given £10/10/-, while the Whig maintained a modest silence about its own contribution.14

Other politicians had followed Carson’s initial lead, although not as enthusiastically as his gift of £50: Craig also gave £10/10/-, while Richard Dawson Bates, despite being chairman of the Ulster Unionist Council and the other honorary secretary of the Fund, chipped in a mere fiver. Almost 300 individuals sent various sums of money to the Old Town Hall, including £1 from an anonymous donor who described herself as “A woman of no importance.”15

As well as individual donations being sought, fundraising events were held, among them a “Grand Variety Concert and Cinematographic Entertainment” held in the YMCA Hall in Wellington Place on 29th March and a “Grand Aquatic Championship Gala” organised by the Donegall Amateur Swimming Club at the waterworks on the Antrim Road on 27th August, although on the latter occasion, “The weather unfortunately was not favourable, and marred to a considerable extent the enjoyment of the admirable programme which had been arranged.”16

The YMCA Hall in Wellington Place

The practice of raising funds locally was open to abuse. In October, four men were charged with obtaining money under false pretences – a witness stated that “…the prisoners came him and said a mate had got into trouble. They had a sheet which bore the heading Loyalist Relief Fund. Witness gave them five shillings.” A sister of the man in trouble said that the four had no permission from her to collect for his defence, “…although she considered it kind of them to do so.” The four were acquitted.17

A revived Fund

The Fund was initially wound up in the third week of November 1921, but was revived just over a week later. The revival was prompted by two sectarian bombing attacks carried out by the IRA on trams in Corporation St and Royal Avenue on 22nd and 24th November respectively: seven unionist civilians were killed and many more wounded.

The aftermath of one of the IRA’s sectarian bomb attacks on trams (Illustrated London News, 3rd December 1921)

The newspapers’ weekly calls to action now took on a dramatically different tone, with the object of the Fund shifting, from helping unionists expelled from their jobs or homes to aiding the relatives of unionists killed or wounded in the conflict:

“We appeal to all citizens to support the Relief Fund for the dependents of Loyalists killed or injured during the outrages committed in the city. It is the absolute duty of every loyal man to see that those who have been so cruelly robbed of their dearest are spared the suffering and distress which must otherwise follow in the train of their bereavement.”18

Although 501 people were killed during the Pogrom and thousands more wounded, the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Act 1919 created a barrier that prevented some of the victims or their families from seeking compensation through the courts. The Act specified that compensation was only payable, “Where any … person has been murdered, maimed, or maliciously injured in his person, and the murder, maiming or injury is a crime arising out of any combination of a seditious character or any unlawful association” (emphasis added). That clause shut the door to compensation for those who had been killed by the police or military, where an inquest jury decided that the soldier or policeman responsible had been acting “…in the course of the execution of his duties.”19

This presented a particular problem for unionists in the early part of the Pogrom: of the 35 unionist civilians killed from July to December 1920, 20 were killed by British soldiers and another three by the Royal Irish Constabulary; the dependents of two-thirds of the unionists killed in this period were therefore barred from seeking compensation. In 1921, the proportion dropped to 17% and in 1922, it fell further to just 11%. By then, inquest juries had become diligent in specifying if those killed, whether nationalist or unionist, had been killed by members of “an unlawful assembly.”

The committee of the revived Fund consisted of Craig as the patron, Captain Herbert Dixon as chairman, H. Trevor Henderson and Robert Baird acting as treasurers and Joseph McConnell, Sam Bradley & S. Donald Cheyne as secretaries. However, over time, it would be their wives who would actually play more prominent roles.20

This was perhaps exemplified by Lady Ruby Carson. Her husband had helped launch the initial fund with a donation of £50, but in December 1921, she wrote to the committee, enclosing a cheque for £500 which she had received from an anonymous donor in London.21

In parallel to such high-profile contributions, unionists put enthusiastic effort into fundraising at grassroots level. Members of Women’s Unionist Associations from various parts of the city did door-to-door collections in their localities, while there were also collections among the members of loyal orders and flute bands. On Christmas Eve, carol singers in Whitehead, just north of Belfast, “made a circuit of the picturesque seaside resort” and raised £12/12/6 in the process. Donations were also received from Orange lodges as far afield as the United States and Canada. By the end of 1921, the revived Fund had already collected £2,647.22

By publishing the individual amounts raised by such efforts, the newspapers helped foster a sense of competitive fundraising, as those involved would see their efforts acknowledged publicly.

This was particularly the case with workplace collections. At the end of January 1922, the Belfast News-Letter praised the “generosity of Queen’s Island employees.” Although they had carried out the original expulsions, the News-Letter said, with no apparent trace of irony, that:

“The Belfast shipyard workers have always been noted for their practical sympathy with those who are in suffering and distress, and in connection with the fund in aid of the widows and orphans of the men who were stricken down without a moment’s warning by the assassin’s bomb or revolver they have given one more striking proof of their generous disposition and public spirit.”23

To give the shipyard workers their due, their contributions to date then stood at £1,100 or one-third of the total amount raised by the Fund.

The Anderson family

In mid-January, the committee was told that “…up the present 97 cases have been carefully investigated, and sums ranging from 10s [shillings] to 60s per week have been allowed to bereaved families. Numerous other cases are being investigated.” One particular example was highlighted both by Grant, secretary of the Fund’s administration committee, and by Dixon, in a speech he made to the East Belfast Women’s Unionist Association on the same day – this was a particularly poignant case, that of the children of the Anderson family.24

Ewart’s Mill on the Crumlin Road, where Arthur and Lizzie Anderson worked

Andrew and Lizzie Anderson and their five children lived in Hooker St in Ardoyne; both parents worked in the nearby Ewart’s Mill. Just before 8 o’clock on the morning of 11th January 1922, their eldest son, also named Andrew, then aged 15, was the first to leave for work. He was at the end of the street at its junction with the Crumlin Road when he heard the sound of an explosion – a bomb had been thrown at a tram further up the Crumlin Road. He was about to run to warn his parents when he saw three or four armed men, at the other end of the street where it met Butler St, who began shooting. He took cover in Distraeli St on the other side of the Crumlin Road.25

A neighbour saw the couple standing outside their house as Andrew locked the front door – she then saw flashes and heard shots coming from an entry at the far end of the street. Lizzie crumpled on the footpath. Other neighbours ran to carry her body into the house, while Andrew, though also shot, was able to stagger indoors. By the time their son made it home, both his parents were lying dead on the kitchen floor.26

Grant saw to it that the Fund paid for the Andersons’ funeral. Their orphaned children, aged from 18 down to 4, were taken into the care of a local clergyman, Reverend Montgomery, who arranged new accommodation for them, also paid for by the Fund. In 1923, the children, through Reverend Montgomery, applied for £2,000 compensation. The magistrate, although agreeing that it was a brutal case and saying that Reverend Montgomery “deserved every credit for the interest he had taken in the family”, only awarded them £650.27

This case highlighted another failing of the Criminal Injuries Act: any compensation awarded would be a cost to be met by the local authority. As a result, magistrates, keen to avoid increasing the burden on ratepayers, could be niggardly in their awards. John McDonagh was wounded in the hip by armed intruders who broke into his home in Lavinia St in the Lower Ormeau on 31st May 1922. He was unaware that he could claim insurance benefit and had to rely on a payment of 30/- a week from the Fund – when he claimed for £200 compensation, the magistrate hearing his case snarled, “The ratepayers should not have to pay for his ignorance. I will give a decree for £4O.”28

The entrance of the unionist grand ladies

In May 1922, Grant reported that “…since the establishment of the fund 256 dependents of 66 persons who had been killed had been assisted by the committee, and that, in addition, many dependents of 134 persons who had been wounded had received much-appreciated financial aid.”29

The following month, Lady Cecil Craig addressed a cake fair and bazaar organised by the Duncairn Women’s Unionist Association to raise money for the Fund and told them that “…on average relief was given to five hundred dependents each week. The burial of thirty-eight Loyalists had been undertaken, and a sum of about £3,500 had been expended to date.”30

With so many people in need of assistance, the grand ladies of unionism decided, just two days before the Twelfth, that a dramatic intervention was required.

They announced their intention to hold a bazaar to raise money for the Fund – it would feature stalls named after the House of Commons and Senate of Northern Ireland, as well as various unionist organisations, with one of the ladies in charge of each stall:

Senate Stall – The Marchioness of Londonderry

House of Commons Stall – Lady Craig

Ulster Women’s Unionist Council Stall – The Duchess of Abercorn

Orange Women’s Stall – The Grand Mistress [not named]

Ulster Unionist Labour Association Stall – Mrs J.M. Andrews

Loyalist Relief Fund Stall – Hon. Mrs Herbert Dixon

Ulster Protestants for Peace with Honour Stall – Mrs R.J. McKeown

Ulster Sports’ Stall – Mrs Howard Ferguson31

(L-R) Edith Vane-Tempest-Stewart (Marchioness of Londonderry), Lady Cecil Craig, Rosalind Hamilton (Duchess of Abercorn)

The bazaar was to be held on 24th and 25th November at Stormont Castle, the Craigs’ residence, which they had decided to make available.

During the autumn, a vast range of subsidiary fund-raising activities were run as the various ladies competed to raise money – a flag day for the House of Commons Stall, a flag day and flower day for the UULA Stall, a whist drive in Orangefield and a jumble sale in Albertbridge Road for the Fund stall.32

The Cromac Women’s Unionist Association ran a cake fair on 27th October with “Half-Hour Entertainments, Concerts, Recitations, Palmistry, Tea, &c.” The following day, their Woodvale & Falls counterparts ran a cake fair and fruit and veg sale, but with no palm-reading.33

A series of balls to raise funds were held at the Carlton Ballroom. While the unionist newspapers’ reporting of the affairs of the titled and the nobility could be obsequious at the best of times, they plumbed new depths of grovelling in their fawning accounts of these dances, with gushing descriptions of each lady’s ballgown and jewellery.34

However, not all was fun and games and soirées. These unionist ladies were consummate political operators in their own right – Lady Craig was a founder member of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council, served as its vice-president for eleven years and was also vice-president of the Ulster Unionist Council for more than twenty years. The ladies’ choice of dignitary to formally open the bazaar spoke volumes.35

They picked Lilias Margaret Frances, Countess of Bathurst, who was the owner of the Morning Post, an arch-conservative and virulently anti-Irish newspaper in London; she was viewed as “…a very staunch and consistent friend of Ulster in the trying times which the province has experienced daring the last few years.”36

Countess Bathurst had her priorities straight: on arrival in Belfast, before proceeding to Stormont Castle, she first arranged a meeting with “…representatives of the local branch of the British Empire Union, who will present her with an illuminated address.” She was clearly a senior member of the organisation, which Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh has described as a “…grouping that shared an affinity with emergent fascist ideology in Europe.”37

In her speech to open the bazaar, she showed these colours, stating “…her unalterable conviction that a race such as Ulstermen, who were honest and hard working, loyal, true, and faithful, could not possibly be governed by a race that had none of those attributes.”38

(L) Stormont Castle, where the Loyalist Relief Fund bazaar was held; (R) Lilias Margaret Frances (Countess of Bathurst), a proto-fascist who performed the opening ceremony

In terms of fund-raising, the bazaar was an outstanding success – in mid-December, the treasurer of the organising committee reported to them that it had raised £12,404. Considering that this is equivalent to over £761,000 in today’s money, it was an absolutely phenomenal achievement in any terms.39

With Christmas approaching, the Fund’s activities took on a more seasonal dimension. A fancy-dress ball was held in the Ulster Hall on 19th December where, predictably, “The costumes were most original and picturesque, and elicited much admiration.” Somewhat less predictably, “Mr J.F. Harris came as A Cigar.”40

A much more wholesome event was held in the YMCA Hall the following day, when 300 children who were receiving aid from the Fund were treated to tea, a cinema show and a visit from Father Christmas who distributed gifts.41

The children’s Christmas party hosted by the Loyalist Relief Fund: Father Christmas is in front of the Union Jack, William Grant is above it (Belfast Telegraph, 21st December 1922)

Assistance given by the Fund

The last of the killings in Belfast was at the start of October 1922, but their impact in terms of destitution was long-lasting, as those left bereaved also struggled to cope with the loss of a breadwinner.

A meeting of the Fund’s committee in March 1923 heard that on top of the £12,404 from the Stormont bazaar, donations and other fundraising efforts had brought in a further £10,720 making a total of £23,134; in today’s terms, that was over £1.4 million.

The revived Fund had paid out £9,595 since December 1921, which was broken down into three-month chunks:

- To 18th March 1922: 440 dependents; total payments averaged £97 per week

- To 17th June 1922: 870 dependents; £169 per week

- To 16th September 1922: 920 dependents; £199 per week

- To 16th December 1922: 755 dependents; £148 per week

- To 3rd March 1923 (11 weeks): 555 dependents; £130 per week

So far, over 1,300 dependents had received assistance and the funeral expenses of 45 unionist victims had been paid.42

Some of the stories behind these figures illustrate the extent to which families’ incomes were destroyed – the Fund could only alleviate their hardship to a small extent. These stories came to light as the Belfast Claims Court heard compensation cases and further underline the magistrates’ miserly attitude.

Families could be left destitute by the killing or wounding of a breadwinner

On 20th February 1922, Thomas McNiece was going to a dance in Clifton St Orange Hall when he was fired at in Spamount St in the New Lodge and wounded in the knee. He had to attend hospital for four months and was still out of work by the time his claim was heard ten months later; in the interim, he had received 15/- a week from the Fund. Rather than the £500 compensation he sought, the court awarded him £25.43

Thomas Best, aged 18, had a coal round out of which he gave his mother, Sarah, £4 a week – she said he was her sole support. He was shot dead in Ballycarry St off the Oldpark Road on 21st April 1922. At first, she got 10/- a week from the Fund, an eighth of what her son had been giving her; this later increased to £1 a week. Her husband asked for £5,000 compensation for the loss of their son, the court awarded just £200.44

William Johnston, a shipyard worker from Cavour St off the Old Lodge Road, was shot dead near his home on 8th March 1922. His widow, Annabella, was left relying solely on the £1 a week she got from the Fund. She claimed £3,000 for the death of her husband, she was only given £350.45

A different William Johnston was a Special Constable killed by the IRA in Louisa St in the Marrowbone on 18th April 1922; his widow received 30/- a week from the Fund. Margaret Patton’s husband Andrew was killed by British military, thus preventing her from claiming compensation, after a mob attacked St Matthew’s church on the Newtownards Road on 22nd November 1921. She disputed the inquest jury’s finding, saying he had been killed by an IRA bomb, which would have re-opened the door to compensation. He was buried jointly with another man who was killed by the bomb – the Ulster Imperial Guards marched in their funeral cortege. She also received 30/- a week from the Fund.46

Although it might appear from this that the dependents of dead loyalist combatants received higher payments from the Fund than those of dead civilians, there was actually no such hierarchy of victims. William Campbell was an inspector of gas meters, earning £262 a year, or £5 a week; on 24th March 1922 he was shot dead in Ludlow St in the New Lodge. The Fund gave his widow, Annie, £2 a week, a third more than the widows of Johnston and Patton. But more importantly – and assuming she was not working – even with the Fund’s assistance, her income was still only 40% of what it had been prior to the killing of her husband. Her world had collapsed in more ways than one.47

Summary and conclusions

The Loyalist Relief Fund was initially established in the autumn of 1920 as a blatant exercise in whataboutery.

Its founders sought to emulate what the Expelled Workers Relief Committee had managed to achieve within a few months of its foundation, but they struggled to provide a credible rationale for the Fund’s own existence. While unionists were indeed forced from their homes, they suffered no mass expulsions from workplaces on the lines of the attacks on Catholics and “rotten Prods” at the outset of the Pogrom. The fact that donations were therefore sought to alleviate the distress of largely-imaginary victims may help to explain why the Fund initially failed to strike a chord among unionists.

While the EWRC was founded by those who had themselves been expelled from the shipyards and other workplaces, the Fund was set up as a piece of political theatre and led by those who were complicit in those initial expulsions: the Ulster Unionist Council and the UULA. The central involvement of the sectarian William Grant strikes an especially jarring note – he seems to have had an equal capacity to relieve or inflict hardship, depending on whether someone lived in one part of York St or another.

But when the Fund was revived following the IRA’s November 1921 tram bombings and its objective switched to helping less-imaginary victims – the dependents of unionists who had been killed or wounded – then its appeal increased enormously. Donating to tangible and real people allowed unionists to rally round to support those of their community whose lives had indeed been devastated.

The adoption of the Fund as a charitable project by leading unionist women, not all of whom were simply the wives of the Fund’s male committee members, lifted its activities to a whole new level.

Now, ordinary unionists were galvanised around the Stormont Castle bazaar and for all the bowing and scraping to those who possessed titles, all the nauseating fripperies relating to ballgowns and the stellar role offered to a proto-fascist – whose involvement is a clear indication of the wider associations of the unionist leadership – the raising of the equivalent of over £1.4million in current terms was a simply staggering feat.

It meant that more assistance could be given to those who were in dire need of it, particularly when their routes to legal compensation were either completely blocked by the provisions of the Criminal Injuries Act or frustrated at the hands of parsimonious magistrates in the Claims Court. The payments by the Fund were by no means lavish, but without them, the children of the Andersons and the hundreds of others helped by the Fund would have had no safety net at all.

Put simply, the Loyalist Relief Fund allowed some very despicable people to do some good for some very deserving people.

References

1 https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/bills/article-1633409/Historic-inflation-calculator-value-money-changed-1900.html

2 Austin Morgan, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p274.

3 Emmet O’Connor, Rotten Prod: The Unlikely Career of Dongaree Baird (Dublin, UCD Press, 2022), p51.

4 Ibid, p52.

5 Belfast News-Letter, 2nd October 1920.

6 Robert Lynch, The Partition of Ireland 1918-1925 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2019), p171.

7 https://census.nationalarchives.ie/search/

8 Belfast News-Letter, 15th October 1920.

9 Derry Journal, 23rd July 1920.

10 Diarmaid Ferriter, William Grant, Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/grant-william-a3575

11 Statement of Sergeant Bruen [sic – Bruin], Henry St Barracks, Belfast outrages, National Archives of Ireland, TSCH/3/S11195.

12 Belfast News-Letter, 31st August 1922.

13 Northern Whig, 19th January 1921.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Northern Whig, 30th March 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 29th August 1921.

17 Belfast News-Letter, 22nd October 1921.

18 Belfast News-Letter, 29th November 1921.

19 https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1919/apr/15/criminal-injuries-ireland-bill

20 Belfast News-Letter, 29th November 1921.

21 Northern Whig, 30th March 1921.

22 Northern Whig, 29th December 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 31st December 1921, 4th & 6th January 1922.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 31st January 1922.

24 Belfast News-Letter, 18th January 1922.

25 https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Down/Pottinger__part_of_/Grove_Street_East/221296/; Belfast Telegraph, 11th January 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 10th February 1922.

26 Belfast News-Letter, 10th February 1922.

27 Belfast News-Letter, 18th January 1922 & 15th November 1923.

28 Northern Whig, 20th September 1923.

29 Belfast News-Letter, 4th May 1922.

30 Northern Whig, 22nd June 1922.

31 Belfast News-Letter, 11th July 1922.

32 Belfast News-Letter, 29th September, 5th, 10th, 13th & 20th October 1922.

33 Northern Whig, Belfast Telegraph, both 21st October 1922.

34 Belfast News-Letter, 6th & 20th October 1922.

35 Frances Clark, Dame Cecil Mary Nowell Dering Craig, Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/craig-dame-cecil-mary-nowell-dering-a2141

36 Belfast News-Letter, 28th October 1922.

37 Belfast News-Letter, 24th November 1922; Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, ‘The Belfast Pogrom and the Interminable Irish Question’ in Studi Irlandesi, A Journal of Irish Studies, Volume 12, 2022, p171-193.

38 Belfast News-Letter, 24th November 1922.

39 Northern Whig, 15th December 1922.

40 Northern Whig, 20th December 1922.

41 Northern Whig, 21st December 1922.

42 Northern Whig, 10th March 1923.

43 Belfast News-Letter, 16th December 1922.

44 Belfast Telegraph, 21st November 1923.

45 Belfast News-Letter, 13th November 1922.

46 Belfast News-Letter, 2nd June 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 23rd December 1922; Northern Whig, 28th November 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 19th January 1922 & 14th March 1923.

47 Belfast News-Letter, 23rd December 1922.

Leave a comment