As this is the inaugural post on this blog, a logical place to start is with the term “pogrom” itself, as using it to describe what happened in Belfast from 1920-1922 proved to be contentious with perpetrators, contemporary observers and historians in the hundred years since.

This article is based on a paper titled “Belfast 1920-1922: what happened, what to call it?” presented to the annual conference of Universities Ireland on 6th November 2021.

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes.

What is a pogrom?

“Pogrom” is a Russian word, meaning “desolation” or “devastation”; it first began to be used in the English language in the late Nineteenth Century to describe the attacks on Jews that were happening in Russia at that time.

There are many definitions of a pogrom, some academic, some dictionary and there are blurred boundaries between what constitutes a pogrom and what constitutes an ethnic riot. The definition that I prefer – mainly for its accessibility – is that offered by the Encyclopaedia Brittanica:

A mob attack, either approved or condoned by authorities, against the persons and property of a religious, racial, or national minority.

However, I would argue that what began in Belfast on 21st July 1920 fails to meet this definition, for two reasons.

The first relates to the phrase “approved or condoned by authorities.” In Ireland in 1920, the authorities were the British administration in Dublin Castle and the forces at their disposal – and as the following illustrations show, both the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the British Army tried to stop the violence in Belfast.

RIC barricade, Seaforde St, Ballymacarrett, Illustrated London News, 4th Sept. 1920

Military armoured car, Foundry St, Ballymacarrett, Illustrated London News, 1st Sept. 1920

In Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Michael Farrell wrote that in July 1920, British troops behaved with “fine impartiality” when they intervened to separate rival Protestant and Catholic mobs.1 If anything, they were partial on the side of the Catholic minority – there were twenty-one people killed in Belfast that month, the military were responsible for all but two of those deaths and of the nineteen people they killed, eleven were Protestant and eight Catholic.

The second reason why the violence of July 1920 in Belfast falls short of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica definition is that it wasn’t directed at a “religious, racial or national minority” – singular. While Catholics were undoubtedly the primary targets, another minority was also attacked – these were the so-called “rotten Prods”, socialist and trade unionists who were perceived by loyalists to be just as disloyal as Catholic “Sinn Feiners.”

Headquarters of striking engineering workers, February 1919

In January 1919, Belfast had been largely paralysed by an engineering strike over working hours which continued until February and which actually lasted twice as long as the vaunted Limerick Soviet. This increased working-class militancy was also reflected in the January 1920 elections to Belfast Corporation, when Labour won more seats than Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party combined. Both the strike and the election results were of course influenced by the successful October Revolution of 1917 in Russia, but even tepid forms of “Bolshevism” represented a potential threat to the unity of the British Empire and the place of northern industrial capital within it.

“Pogrom” – early usage

Brian Feeney says the word “pogrom” was being used extensively by the Belfast nationalist paper, the Irish News, by September 1920. However, it began to be used almost immediately in the nationalist press elsewhere to describe the violence that was happening in Belfast – the Dublin Evening Telegraph was already using it by the very next day after the initial outbreak: “The Catholic workers are not prepared to risk their lives in the pogrom that has been organised.” The Freeman’s Journal used it in a headline the day after that.2

More important than when it began to be used is why it began to be used.

The reason is that those on the receiving end of the initial violence instantly drew analogies between their plight and what they thought an actual pogrom involved.

The first image above, taken from the Illustrated London News of 31st July 1920 , shows a mob photographed in the very act of looting a shop in Kashmir Road in Clonard in west Belfast. Note that this isn’t a mere handful of hooligans, it’s a crowd that fills the entire street between the shop and the photographer’s vantage point; this crowd has invaded the nationalist Clonard area from the unionist Shankill.

The first image above, taken from the Illustrated London News of 31st July 1920 , shows a mob photographed in the very act of looting a shop in Kashmir Road in Clonard in west Belfast. Note that this isn’t a mere handful of hooligans, it’s a crowd that fills the entire street between the shop and the photographer’s vantage point; this crowd has invaded the nationalist Clonard area from the unionist Shankill.

The second image is taken from the 4th September 1920 edition of the same paper. I would describe it as a family “flitting” from the Grosvenor Road as we can’t tell from the photo whether they have already been intimidated into leaving their home or whether it’s a case of them voluntarily moving out before they’re put out.

This image, from the same edition of the same paper, shows a spirit grocers on Beersbridge Road in east Belfast, looted and burned. The licensed trade was one of few businesses in Belfast that were dominated by Catholics, so particular attention was paid by mobs to pubs and spirit grocers.

It was because of events like those shown that nationalists seized on the term “pogrom.” But theirs was only one perspective and there was another one – that of unionism.

“… all means which may be found necessary …”

In the Ulster Covenant of 1912, unionists had pledged that they would use “all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland.” If they said that in relation to mere Home Rule, then they were guaranteed to use all means which they found necessary to defeat a new conspiracy to create an independent Irish republic.

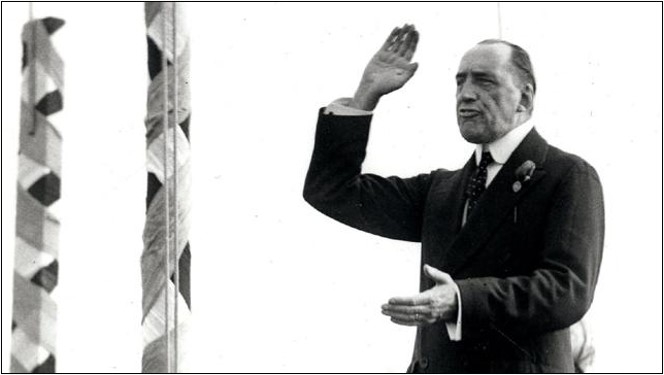

Edward Carson

So, speaking at The Field in Finaghy on 12th July 1920, Edward Carson told his audience: “… we must proclaim today clearly that, come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Fein – no Sinn Fein organisation, no Sinn Fein methods … And those are not mere words. I hate words without action.”3

How to go about defeating the republic posed a problem for unionism – it viewed the authorities in Dublin Castle as too weak and the RIC as too Catholic to be trusted to do it. To defend the union and the link to the empire, it had to turn to its own grassroots base – but the growth of Labour had weakened the cross-class unity on which unionism was based.

Carson saw the danger this represented and so in the same speech on the Twelfth, he said: “… these men who come forward posing as the friends of Labour care no more about Labour than does the man in the moon. Their real object and the real insidious nature of their propaganda is that they mislead and bring about disunity amongst our own people …”4

To rebuild the cohesion of the unionist base, the “rotten Prods” had to be dealt with as well and so they accounted for around 1,850 of the total number of workers expelled from their workplaces when the Pogrom began.5

That then begs the question: what was that total? More broadly, what happened in Belfast in these two years?

Facts and Estimates of the Belfast Pogrom

In terms of the numbers of workers expelled, we only have estimates. Contemporary figures range from 8,000 quoted in October 1920 by James Baird, himself an expelled “rotten Prod” as well as a Labour councillor, to 10,000 applicants for relief from Bishop McCrory’s Belfast Expelled Workers’ Fund the following month. A slightly higher figure of 10,000 men and 1,000 women has since been referenced by Jonathan Bardon and Brendan O’Leary.6

There are also only estimates for other aspects of the violence in Belfast.

As regards evictions, Robert Lynch says 10,000 people were forced to move within Belfast – 8,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants.7

Houses burned out in Antigua St, The ‘Bone, May 1922

No-one has yet compiled a total for the number of houses burned but it definitely ran into hundreds, more likely over 1,000 and possibly more than 2,000.

Lynch also cites various estimates of the number of Catholic refugees made in 1922: 10,000 northern Catholics in Dublin alone in the spring; 30,000 northern Catholics having passed through Dundalk from January to the end of June; 20,000 Belfast Catholics having left the city by November.8

Belfast refugees in Dublin, June 1922

Those evicted, losing their homes or turned into refugees were relatively indirect victims. Among the more direct victims were, according to Alan Parkinson, over 2,000 people wounded by guns, bombs, stabbings and beatings.9

However, the most direct victims were the 499 men, women and children killed between July 1920 and October 1922. This figure is not an estimate.10

The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom

Before getting into the details of those killed, some known unknowns should be highlighted:

First, both Parkinson and I rely heavily on the newspapers’ reports of fatalities, but there is a gap in their reporting as printers in all the Belfast papers were on strike for a month in the summer of 1922.

Second, some deaths were deliberately kept quiet, or as quiet as possible – for example, the mother of Joseph Burns, a member of the Fianna shot and killed by accident in January 1922, wrote to the Military Service Pensions board in the 1930s, saying “I had to take his death quietly as the police were making active enquiries in the case…”; the circumstances of his death remained a mystery until his Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) file was released in 2017.11

Third, some of those killed, currently thought to be civilians, may actually turn out to have been combatants. In the case of republicans, the release of MSPC files is ongoing so there is some prospect of correction. Beyond them is the undocumented role of both the Ancient Order of Hibernians and loyalist paramilitaries – for example, the pallbearers at six funerals of Protestant men between late November 1921 and early March 1922 were provided by the Imperial Guards, a loyalist paramilitary organisation, which at least raises a question as to whether they were members killed in action; I have assumed they were, although there is no way of knowing for sure.

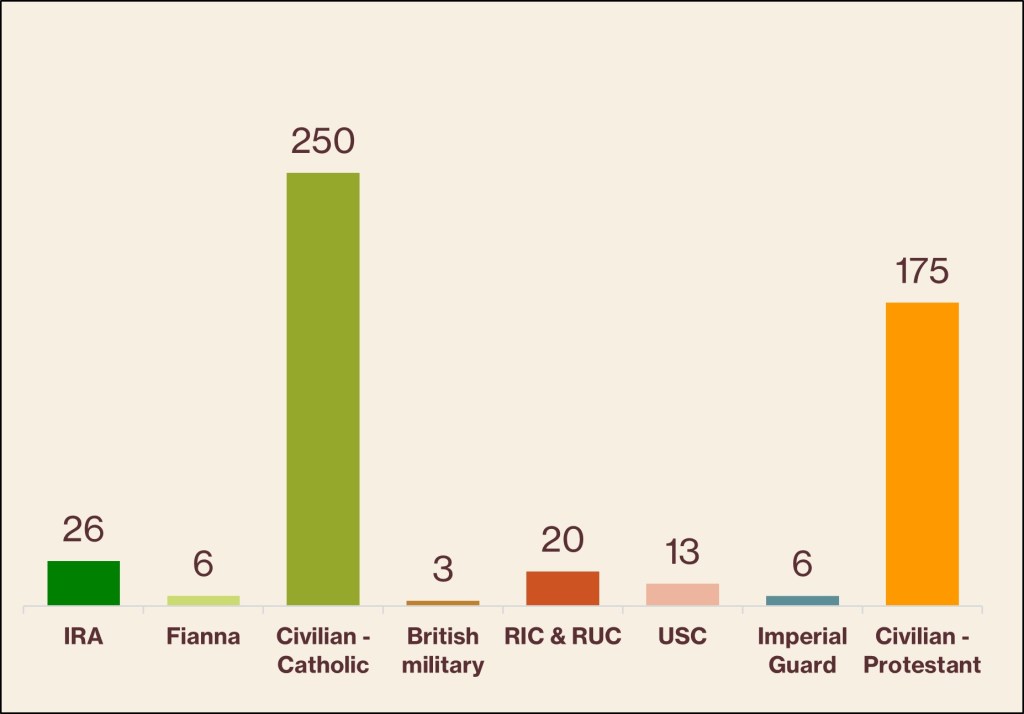

So who were those killed?

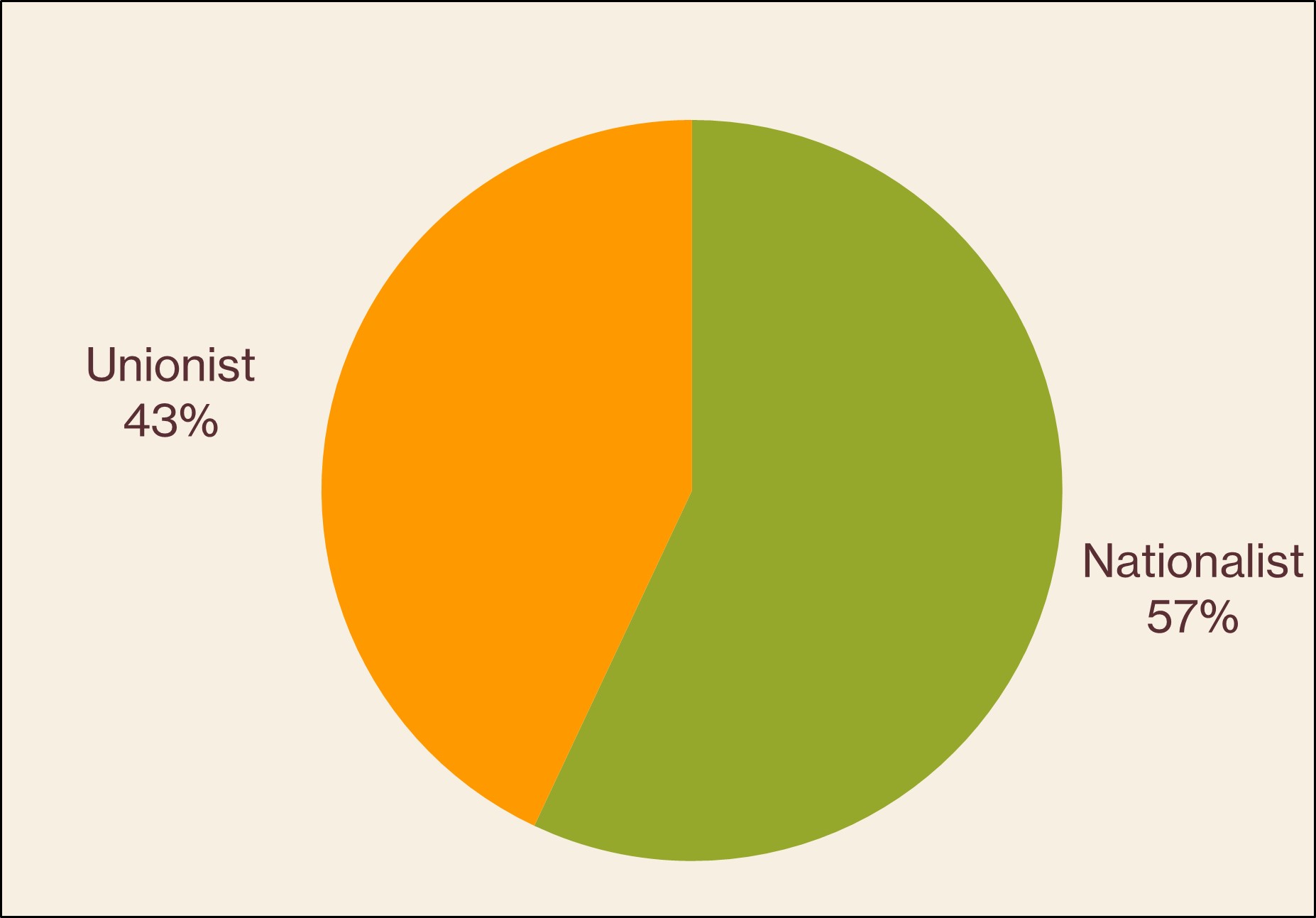

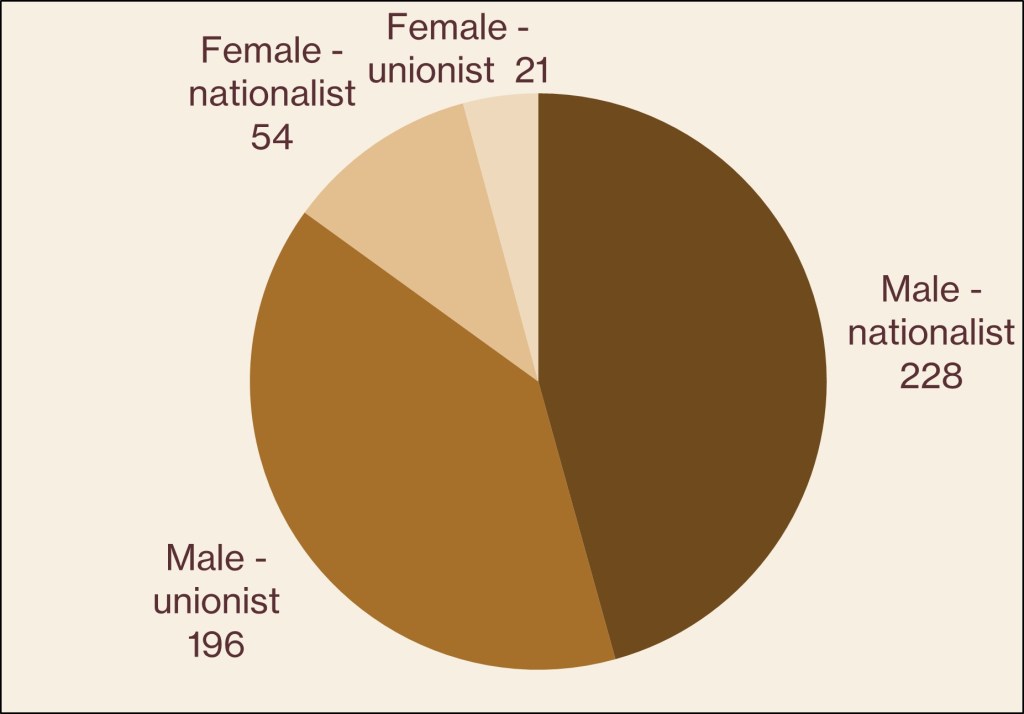

In relation to the first chart above, the population of Belfast in the 1911 Census was 76% Protestant and 24% Catholic, so it is obvious there was a huge disparity between those figures and the percentages of fatalities. As regards the second chart, The Dead of the Irish Revolution states that females made up 4% of those killed on the whole island in the period up to December 1921, so the female fatality figure of 15% for Belfast is a massive outlier to the wider picture.12

When we drill into the figures, we can see the extent to which civilians bore the brunt of the violence on both sides.

If we add up the deaths among all the republican, state and loyalist combatant organisations, they come to fewer than one in five of the total – 85% of those killed were civilians.

Here, the proportion of nationalist to unionist females killed is almost the exact opposite of the percentages for the city population as a whole – 72% nationalist and 28% unionist. Given the social roles played by men and women at the time, that would suggest that most of the violence happened where nationalists lived.

While that is true, it didn’t happen where most nationalists lived. This was the geography of killings in Belfast:

At the time, the highest concentrations of Catholics were in west Belfast – along the Falls Road, in Clonard and the Lower Falls; there, where they had strength in numbers, there were lower levels of killings. Most killings actually happened in the religiously mixed areas of north Belfast – in particular around North Queen Street, York Street and the old Sailortown area between there & Corporation Street, where the fatalities were the highest of any district.

At the time, the highest concentrations of Catholics were in west Belfast – along the Falls Road, in Clonard and the Lower Falls; there, where they had strength in numbers, there were lower levels of killings. Most killings actually happened in the religiously mixed areas of north Belfast – in particular around North Queen Street, York Street and the old Sailortown area between there & Corporation Street, where the fatalities were the highest of any district.

The violence was also ferocious in Ballymacarrett in the east of the city, where a nationalist enclave was surrounded on one side by the River Lagan and on the other three by a hostile unionist population.

It is also worth noting that the IRA was longest-established in west Belfast and only organised later in the north and east of the city.

The conclusion is that the most intense violence took place, not where Catholics were most numerous, but where they were most vulnerable.

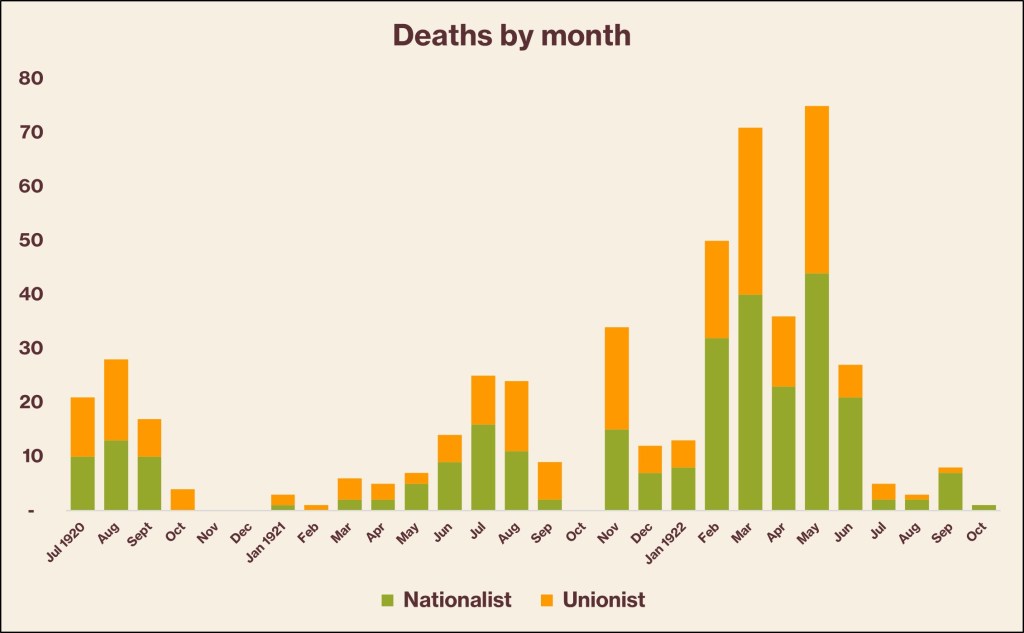

Next, let’s look at the sequence of the killings.

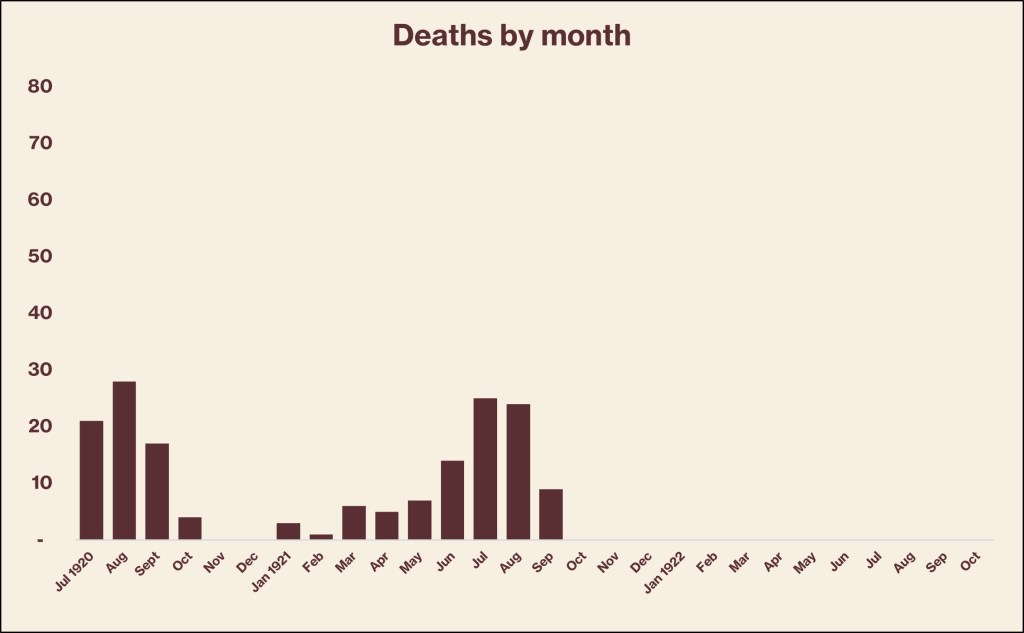

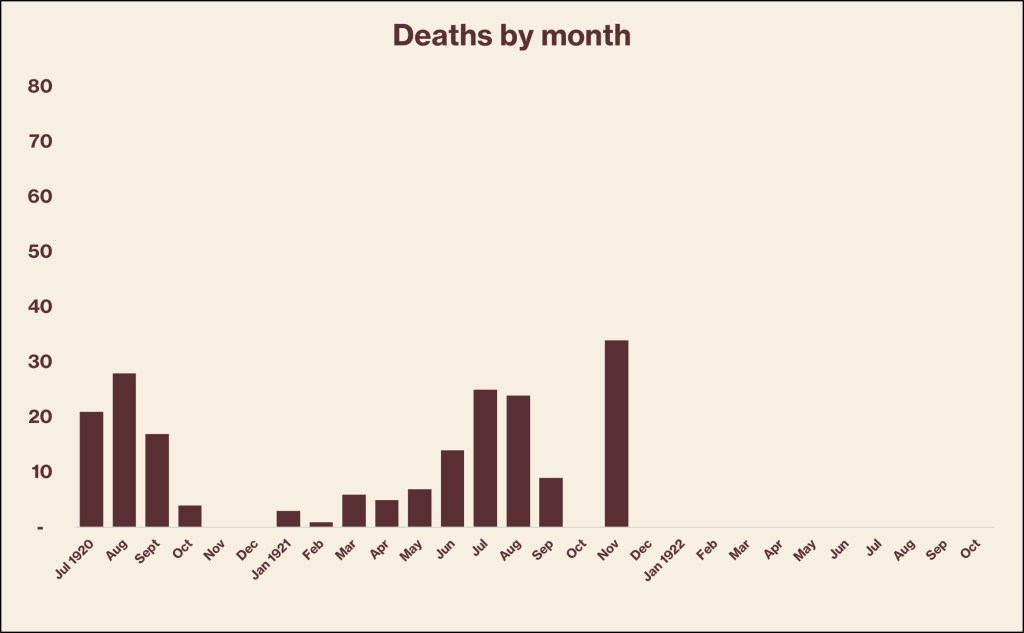

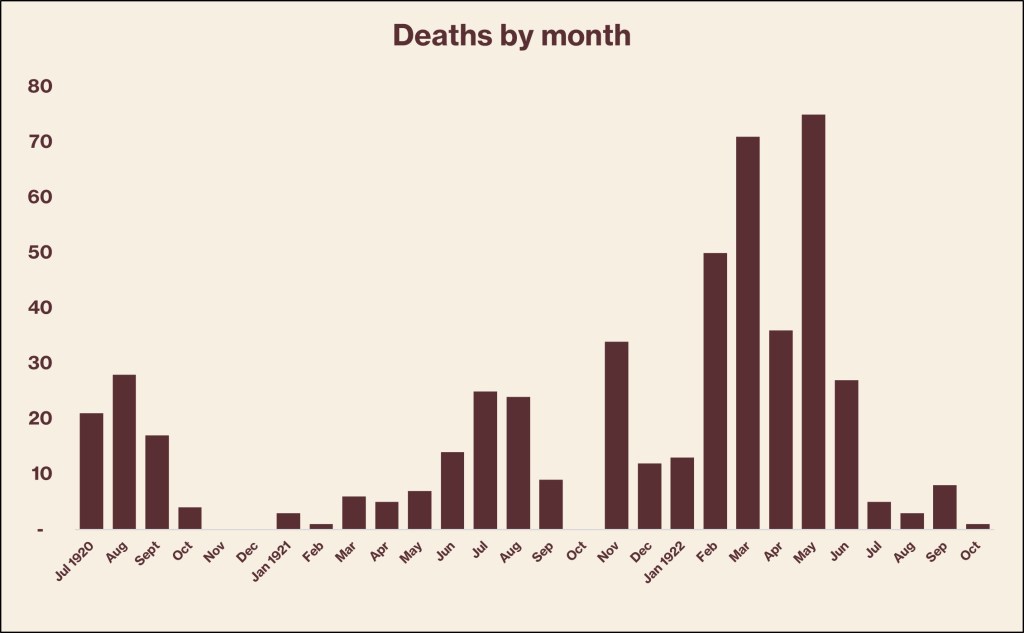

The initial outbreak followed the workplace expulsions in July 1920 and was exacerbated by the loyalist response to the IRA’s killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn the following month. There were relatively low levels until the next peak, which was an eruption around the signing of the Truce in July 1921, followed by a further outbreak around York Street in late August and early September. In October, there were no deaths at all.

November 1921 was a watershed – it was marked by several key events.

Under the terms of the Truce, the A Specials were confined to barrack duties while the B Specials were demobilised – so, nature abhorring a vacuum, there was a revival of loyalist paramilitaries; remarkably, one such group, the Imperial Guards, placed an ad seeking new recruits in one of the main Belfast daily newspapers.

Belfast News-Letter, 11th Nov. 1921

Secondly, the final transfer of responsibility for security and policing to James Craig’s Unionist Government of Northern Ireland happened on 22nd November. Following this, the Specials were fully re-mobilised. An RIC plan to incorporate loyalist paramilitaries into the Specials had been revealed earlier that month, so the plan was shelved as a result but it eventually happened in early 1922.

Finally, in response to a fresh round of attacks in Ballymacarrett near the end of November, the IRA mounted clearly sectarian bomb attacks on trams carrying Protestant shipyard workers in Corporation Street and Royal Avenue.

The combination of these factors meant that November 1921 was the worst month yet for killings – there were thirty-four, all in the last ten days of the month.

But even that was almost dwarfed by what happened in spring and early summer of 1922.

From mid-February, the killings weren’t in waves but were almost continuous and were now widespread across the city rather than being concentrated in particular areas. The B Specials were expanded by the deferred incorporation of loyalist paramilitaries. Some of the worst incidents involving multiple fatalities took place in this period – the Catholic children killed in Weaver Street, the McMahon family killings and killings of civilians in their homes by the police in Arnon Street at the start of April.

May 1922 was the single worst month of the entire period with seventy-five killed – this was linked to the IRA’s “northern offensive” which, in Belfast, began on the night of 18th May.

November 1921 was a watershed in another sense.

In the seventeen months up to then, there had been 164 killed, almost evenly split between eighty-one nationalists & eighty-three unionists. But in the eleven months after that, not alone were there just over twice as many killed in total, at 335, but the proportions killed shifted to three nationalists for every two unionists.

The number of killings dropped significantly after June 1922 – the end of the Pogrom is often explained in terms of the outbreak of the Civil War removing southern support from the northern IRA, but this explanation downplays the agency of those involved in north.

The end of the Pogrom

Firstly, there was an extremely aggressive response by the Unionist government to the May offensive. Clearly alarmed at the co-ordinated aspect of the offensive, the Specials were unleashed: the June 1922 Operations Report of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade to GHQ included an appendix running to fity-two typewritten A4 pages detailing attacks on nationalist areas across Belfast. This onslaught prompted the flood of refugees referred to by Lynch.13

Towards the end of May, following the IRA’s killing of Unionist MP William Twadell, the internment clause of the Special Powers Act was invoked and eventually over 700 republicans and nationalists were interned. Short on prison space, the government began using the SS Argenta as a prison ship, gleefully described by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC – replacement for the RIC) City Commissioner as a “floating internment palace.”14

The SS Argenta

On the republican side, the IRA split of March 1922 had a debilitating impact.

Joe McKelvey’s successor as O/C 3rd Northern Division, Seamus Woods, claimed he had kept 90% of the Division loyal to pro-Treaty GHQ, but a different picture has started to emerge in recent years of a more damaging and violent split. The May offensive was mounted by the pro-GHQ faction, but the anti-Treaty Executive faction in Belfast concentrated on consolidating its own position. In late June 1922, there was a farcical chain of events when the Executive robbed a bank in the morning but by lunchtime, were accusing the pro-GHQ side of having robbed the proceeds of their bank robbery; by early afternoon, there was mutual raiding of each other’s arms dumps, culminating in shots being fired between the two groups.15

Left: Roger McCorley, O/C Belfast Brigade and Tom Fitzpatrick, O/C Antrim Brigade remained loyal to pro-Treaty GHQ in Dublin. Right: Joe McKelvey, O/C 3rd Northern Division was elected a member of the anti-Treaty IRA Army Executive

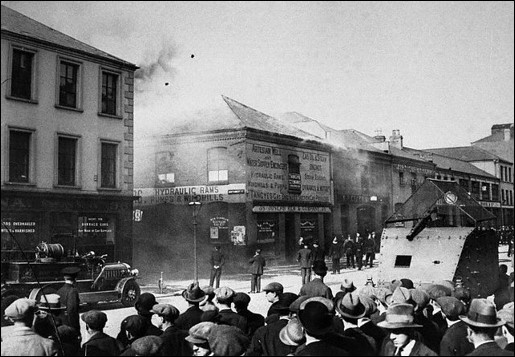

Following the military failure of the May offensive, the IRA in Belfast resorted to an arson campaign against unionist-owned businesses but in reality, this was the last sting of a dying wasp.

The “Falls firebugs” – an arson attack on Rea Engineering, Chichester St, 15th June 1922

At the start of July, the RUC scored a significant intelligence victory when they discovered the HQ of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade at a hall in the Market area. There, they seized arms, ammunition and a treasure trove of documents, among them lists of officers’ names and – incredibly – a list of the names and home addresses of IRA members who had been trained in the British Army during the Great War as machine-gunners, signallers and armoured car drivers.16

Following the failure of the “northern offensive”, the introduction of internment and now this latest intelligence disaster, the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division in large measure broke and ran to the south.

What to call it?

What we now term the revolutionary period had a northern element to it, driven by local members of the IRA, Cumann na mBan and Fianna; in the north and in particular in Belfast, their attempted revolution was met by a determined response from those who wanted to maintain the position of Northern Ireland within the British Empire.

In his Treatise on Northern Ireland, O’Leary calls that response a counter-insurgency, but adds a very necessary adjective, reflecting how it was aimed not directly at the IRA but indirectly at the nationalist population: “a sectarian counter-insurgency.”17

In his latest book, A Difficult Birth, Parkinson has an interesting formulation: “Although this conflict cannot be considered a fully-fledged pogrom, a better term to describe its nature is difficult to find…”18

The word “pogrom” was used by those who suffered a vastly disproportionate share of the violence to describe what was being done to them – it described their lived reality. So, not in a definitional sense because as noted above, what happened doesn’t fit the definition, but in the same descriptive sense in which they used it, “pogrom” is the word that I use.

References

1 Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State, (London, Pluto Press, 1980), p29.

2 Brian Feeney, Antrim: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2021), p146; Dublin Evening Telegraph, 22nd July 1920; Freeman’s Journal, 23rd July 1920.

3 Belfast News-Letter, 13th July 1920.

4 Ibid.

5 Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p269.

6 Freeman’s Journal, 27th October 1920; Sean MacMahon, ‘Wee Joe’: The Life of Joseph Devlin (Belfast, Brehon Press, 2011), p187; Jonathan Bardon, A History of Ulster (Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 1992), p191; Brendan O’Leary, A Treatise on Northern Ireland, Volume 2: Control (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2019), p22.

7 Robert Lynch, The Partition of Ireland 1918-1925 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2019), p171.

8 Ibid, p176.

9 Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Holy War (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2004), p13.

10 Kieran Glennon, The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom – Addendum https://www.theirishstory.com/2022/01/20/the-dead-of-the-belfast-pogrom-addendum/#.YvZh3XbMKUl

11 Joseph Burns file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives, DP934; Burns’ death, though not the circumstances of it, was reported in the Freemans Journal, 14th January 1922.

12 Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (London, Yale University Press, 2020), p12.

13 Adjutant 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 7th July 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCD Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/B/77.

14 Divisional Commissioner’s bi-monthly report, 30th June 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/152.

15 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Commander-in-Chief, 21st September 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/287; O/C 2nd Battalion to O/C No. 1 Brigade, 24th June 1922, in Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

16 Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

17 O’Leary, A Treatise on Northern Ireland, Volume 2, p21.

18 Alan Parkinson, A Difficult Birth: The Early Years of Northern Ireland, 1920-25 (Dublin, Eastwood Books, 2020), px.

I’d rather not give his name in public, but drop me an email: kieranglennon1963 at gmail dot com

thanks for your courteous reply explaining your inclusion criteria. I wonder who your Da was? I admit it – I’m…

I get what you’re saying – in fact, Boyd was a friend of my da when we lived in Belfast…

You mentioned Andrew Boyd in connection with a reprint of Hassan’s “Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom” Strange you…

This comment was originally posted on 18th Oct 2022 by benmadigan (themirror.wordpress.com) but was accidentally deleted when I was doing…

This comment was originally posted by Malcolm Shifrin on 5th Sept 2022 but was accidentally deleted when I was doing…

Leave a comment