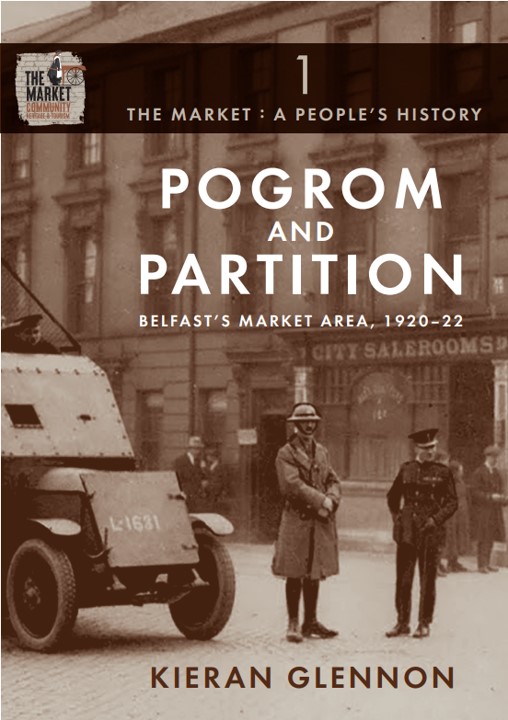

On 28th October, the Market Development Association, in conjunction with the Pangur Bán Literary and Cultural Society, will launch “Pogrom and Partition – Belfast’s Market Area 1920-22”, a local history I’ve written for them. This is an extract from that publication, which examines how the internment clause of the Special Powers Act was applied in the area. It does not pretend to be a representative sample of all those interned across the north, but rather, provides a localised case study.

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes.

The Rathbone Street raid

On 8th July 1922, a hall in Rathbone Street in the Market, which was supposedly the base of St Malachy’s Irish War Pipe Band, was raided by the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC or Specials). The hall was actually the headquarters of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade.

Apart from arms and ammunition, the Specials found a treasure trove of IRA documents. The most valuable of these from a police point of view, and the most damaging to the IRA, were receipts for arms and ammunition, on which the individuals’ signatures were clearly legible; there was a list naming each officer of the staff and component companies of the 2nd Battalion and whether or not they were currently working; another list gave not just the names, but also the home addresses of what were described as “specialists” – IRA members who had been trained as machine-gunners, signallers and armoured car drivers.1

Rathbone Street: the building on the left with a white patch on the wall was supposedly the home of St Malachy’s Irish War Pipe Band. It was actually the HQ of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade.

The RUC wasted no time acting on the information they had uncovered: the night after the raid on the Rathbone Street hall, they swooped on the homes of the eight “specialists” who lived in the Market. Three of the men were not at the targeted addresses, but five others were arrested: James Burns in Raphael Street, brothers-in-law William Delaney and Dennis Dorrien in Riley’s Place, Peter McGurk in Stanfield Street and Peter Murray in East Street.

All five had been noted by the IRA as being trained machine-gunners but they all claimed that they had received this training while serving in the British Army during the Great War – Burns in the North Irish Horse, Delaney and McGurk in the Royal Irish Fusiliers, Dorrien in the Royal Irish Rifles and Murray in the “Royal Ulster Rifles” in the 36th Ulster Division. These pleas cut no ice with the police and while “No arms or incriminating documents were found in any of the homes raided”, their inclusion on lists of IRA members was enough for the authorities and before the end of July, all five had been interned.2

The raid on McGurk’s house had further ramifications. The police found eight other men there, none of whom were residents: John Miley and Peter Fitzpatrick of Annette Street, James O’Hanlon of East Bridge Street, James Gray of Stanfield Street, William Kelly and Hiram McCann of Lagan Street and John Kelly of May Street. They all claimed that they had simply gathered in McGurk’s house to play cards. However, District Inspector James Armstrong of the RUC’s Belfast “A” District, responsible for policing the Market, noted that each of the men was a “suspected firebug.”3

In August, Major-General Solly Flood, Military Advisor to the Northern Ireland government, wrote to Minister for Home Affairs Richard Dawson Bates querying these arrests: “There was ground for supposing, at the time, that they were members of an incendiary gang, subsequent enquiries, however, have disclosed no reason for adhering to this supposition, and I therefore recommend that they be released.”4

The Minister for Home Affairs challenged the police over the continued detention of the men, and a report from the RUC’s Criminal Investigation Department was sent:

“Information was received by the C.I.D. from two sources of a project to destroy the buildings of the Empire Furnishing Co. [in York Street] Among other information received about it was a report that on the night of 11th July a meeting of some of the I.R.A. men concerned in this project would be held at the house of P. McGURK … Subsequently the information about the projected destruction of the Empire Furnishing Co. has been found by the C.I.D. to be mistaken. It is now believed that there was no such project, and that therefore the meeting of these men could not have been occasioned by it.”5

However, DI Armstrong remained adamant that the men had all “long been under suspicion for fire-raising and other offences.”

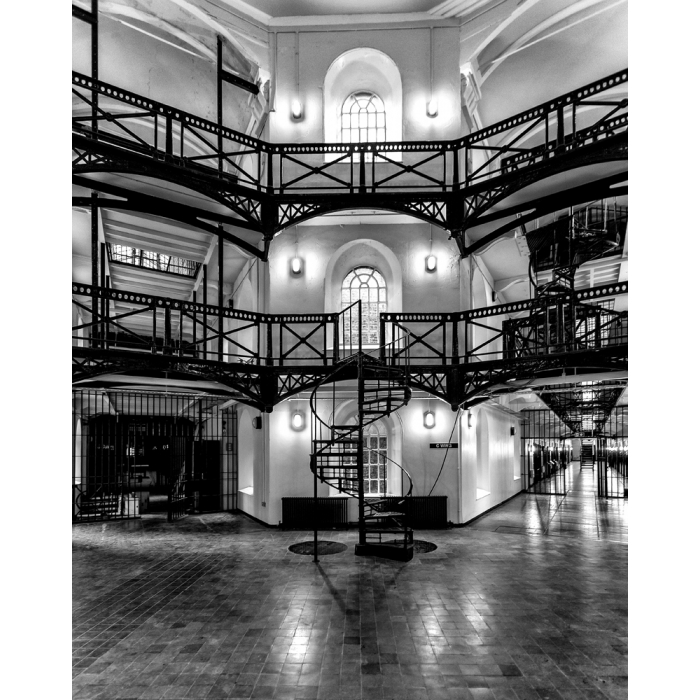

Internees were initially held in Crumlin Road gaol

But there was another complicating factor – the eighth non-resident arrested in McGurk’s house, William Dodds from Market Street: “Dodds is a Protestant but married to a Roman Catholic. All his brothers are Protestants and had to leave their home in Catherine Street North owing to their religion … The Det[ective] Department informed me he has assisted the police on more than one occasion.”6

In a letter to the Ministry of Home Affairs protesting against his detention, Dodds wrote:

“I was arrested in the early hours of the morning of July the 9th whilst playing cards with 8 others in Stanfield St. I am acquainted with the others and had any one of them been connected in any way with any organisation disloyal to His Majesty I would not have been in there [sic] company.”7

Despite the enormous hole which Dodds’ letter knocked in DI Armstrong’s allegations against the other men, they were all interned. Dodds was then released.

IRA internees from the Market

Although few of those initially interned in May 1922 were IRA members, over time an increasing number were – in some cases, as a result of the authorities coming back for a second bite at the cherry.

Joseph Doran was one of the three men arrested while running away from Ferguson’s garage on 18th June; although no incriminating materials were found on them, they were most likely intent on burning the garage as part of the IRA’s arson campaign in the city. He was fined for a curfew violation and required to post a £20 bond as a surety of keeping the peace for the next twelve months. Although the fine was paid and the bond posted, a detention order was issued to keep him in Crumlin Road gaol. His mother was concerned over his continuing imprisonment, so on 13th July, she took the unusual step of writing to Westminster MP Joe Devlin: “He is still confined to prison since he was arrested so if I am not intruding on your valuable time, I would be very thankful if you could bring this case before the proper authorities to see the reason why he was detained.”8

Devlin contacted the Colonial Office in London, who in turn made enquiries to the Secretary to the Northern Ireland Cabinet in mid-August. What Mrs Doran didn’t realise was that just over a week before she wrote to Devlin, Dawson Bates had signed an internment order against Doran, so by the time she wrote the letter, her son was no longer in Crumlin Road but had been transferred to the prison ship Argenta.9

The SS Argenta: used as an internment prison in 1922

Another of the men captured on the same occasion as Doran, Joseph McGlade, was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment, due to expire in late July; an internment order was signed against him at the start of the month so that he would be interned immediately on completion of his sentence. The third man arrested that night, John Donegan, was fined in court, also for a curfew violation; his internment order was part of the same batch as Doran’s and McGlade’s, all signed by Dawson Bates on 5th July.10

Joseph McDonnell from Lagan Street had been arrested and prosecuted under the Firearms Act for possession of one round of ammunition; when his case came to trial on 21st July, it emerged that the round of ammunition, a cartridge four inches long, was actually an anti-tank bullet which a friend in the army had brought home as a war souvenir from Germany. McDonnell was acquitted. The following day, RUC City Commissioner Gelston wrote to the Inspector General, recommending McDonnell’s internment, purely on the grounds that he “was observed to frequent the company of McGlade and Donegan (now interned) two men known to be connected with malicious burnings in the City.” McDonnell was interned four days later.11

Devlin was not the only politician contacted by internees’ families. Rose O’Hanlon, mother of James, one of the seven “suspected firebugs” arrested in Peter McGurk’s house, wrote to no less a figure than Prime Minister James Craig asking him to “have his case seen into and released to his broken hearted mother.” McGurk’s wife Ellen went to the very top of unionism, writing to Edward Carson, by then a member of the House of Lords at Westminster, “to see if you could do anything for me on behalf of my husband.” Both requests eventually made their way to the desk of Dawson Bates, who respectfully informed Craig and Carson that the men had been duly interned.12

Henry Crofton was treated in the same way as McGlade. Documents found in the course of a raid on his lodgings had led to the original raid on the hall in Rathbone Street. While he was still serving a four-month sentence for possession of seditious documents, an RUC report stated: “His sentence terminates on 5-12-22. He is strongly suspected of being a member of the Republican Party, with very extreme views. In the interest of the peace of the City I strongly recommend his internment on termination of the sentence he is now undergoing.”13

An internment order against him was signed in mid-November, but he was left under the impression he would walk free once his four months were up. He was allowed get to within seconds of liberty before his illusions were shattered:

“ When were you released?

I only got as far as the office. I was interned then, when I was released from the four months sentence.

You were released about November?

Yes, and re-arrested at the gate. And interned on the Argenta and brought down to Larne.”14

As well as the Argenta, internees were also sent to Larne Workhouse

Wrong men, wrong place, wrong time

Daniel Flannery was another resident of the Market who was interned – but he had lived in the area for precisely one day when arrested. An ex-soldier, with nine years’ service in the Inniskilling Fusiliers and five wound decorations from the Great War, Flannery had returned to his native village of Killenaule in Tipperary after being demobilised, but being an ex-serviceman, was warned by the local IRA to leave the area.

He secured work in the Government Instructional Factory in Ormeau Avenue, but was lodging in Ardoyne; wishing to live nearer his place of work, he moved to Hamilton Street in the Market on 20th May, with the intention that his wife and children would soon join him.

The next day, the house, regarded by the RUC as “a well-known Sinn Fein den frequented by the most extreme I.R.A. men”, was raided. Flannery “was hiding under a bed and could not satisfactorily account for himself or his movements.” He was interned and it took the authorities three months to admit that he had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was released on 23rd August, but by then, his job in the government-run business had been given to someone else.15

Joseph Hawkins from Stanfield Street was a member of C Company, the main IRA unit based in the Market; in January 1922, he had been sentenced to two months’ imprisonment for possession of ammunition. Believing him to be “a dangerous member of the I.R.A.”, the RUC raided his home on 23rd May, intending to intern him.

But Hawkins was not there so instead, the police took away his father, also named Joseph, aged 56. Joseph Senior was interned on 19th June and even after his eventual release in November 1923, the RUC still refused to acknowledge their mistake, insisting that Joseph Senior “was for many years a well known member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and associated with Peter Burns, also an I.R.B. man.”16

Internees being taken through Belfast, 22nd May 1922

Another member of C Company, Simon McStravick from Stanfield Street, had been sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment on 22nd May for possession of a revolver and five rounds of ammunition.

The following day, his father James was arrested. Despite a letter from the Ancient Order of Hibernians stating that he was one of their members and “an uncompromising opponent of Sinn Fein”, the RUC insisted that he was a disreputable person, citing seven previous convictions for drunkenness and fighting going back as far as 1892. More seriously, they claimed he had detained common criminals on behalf of the IRA Truce Liaison office in St Mary’s Hall; this allegation was made on the basis that “information was received from a person whom the police suspected was implicated in crimes of an ordinary character, including larceny, hold-ups &c, and for which he was arrested by the I.R.A.” On the basis of this informer’s claim, McStravick remained interned until 30th December, only being released in order to see his other son who was then “in a dying condition.”17

Patrick Quinn from Cromac Street was interned in even more ridiculous circumstances. Among the documents found in the Rathbone Street hall were a number of receipts for money received, signed by a “P. Quinn” – most likely Patrick Quinn from Eliza Street, who was a member of C Company. The Cromac Street Patrick Quinn was arrested on 11th August and was adamant that “my name attached to these documents is an absolute forgery”. He had a convincing case – the signatures on the receipts signed by “P. Quinn” have two distinctively different styles of handwriting and whoever signed one of them seemed to believe that the name Quinn was spelled with only one N.

Even DI Armstrong had to admit that “little is known about this man beyond the finding of the documents.” However, that did not deter him from stating that “in my opinion he should be interned as he is fit for anything” – Armstrong claimed that he was the ringleader of a gang responsible for a string of robberies from shipments passing through Belfast port. Quinn remained interned until July 1924.18

In effect, Joseph Hawkins and James McStravick were interned for being the fathers of IRA members, while Patrick Quinn was interned just for having the same name as one.

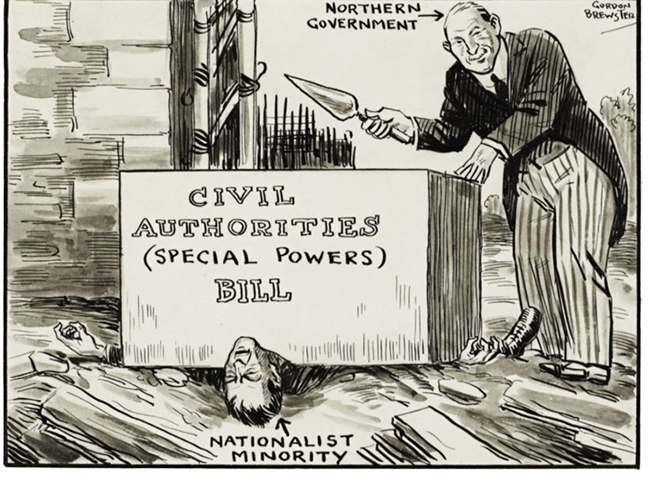

Opposition to the Special Powers Act

Charlie Connolly tries to outwit the authorities

Charlie Connolly, another member of C Company, was high on the authorities’ list of targets for internment, as he had been acquitted on arms charges a few months previously.

DI Armstrong reported: “I regard Charles Connolly as one of the most dangerous men in the district.” Armstrong was obviously still aggrieved at Connolly having beaten the arms charge in court the previous May: “There can be no doubt he was engaged in the conversion of a shell into a road or other mine, although he was acquitted at the Commission. His demeanour in the Court was quite in keeping with his being a member of the I.R.A.”19

In mid-August, an internment order against Connolly was signed. However, the RUC could not find him – his home at 95 Joy Street was raided on 15th August, again on the 18th and again on the 22nd, all without success. He remained on the run until 26th January 1923, when he was finally captured at home – he was transferred from Crumlin Road gaol to the Argenta the next day.

The following week, his wife wrote to the authorities, voicing concern that she hadn’t heard from him since his arrest; curiously, her letter was sent from 63 Joy Street. This would appear to have been part of a pre-arranged plan Connolly and his wife had devised, for around the same time, he wrote to the Ministry of Home Affairs from the Argenta:

“I am in receipt of an internment order handed to me in Belfast Prison, & intended for Charles Connolly, of 95 Joy St.

As I am Charles Connolly of 63 Joy St I fail to see how anything in the order concerns me. This matter if delayed being likely to endanger my means of livelihood, I trust you will give it your earliest attention.”20

Connolly’s letter prompted confusion in the Ministry, with a perplexed civil servant writing to the RUC wondering which address was correct, which Charlie Connolly had they been after and which one did they now have on the Argenta? An irate City Commissioner Gelston sent a report back up the chain of command, stating “I beg to state that there is no doubt whatever but this Charles Connolly of 95 & 63 Joy Street, is one and the same person.”21

The RUC had Connolly behind bars at last and weren’t about to be taken in by a mistaken-identity ruse.

Friends in high places

Joe McPeake from Little May Street was one of the local IRA members who fled south of the border and ended up enlisting in the Free State Army, being stationed in Dundalk. By 12th March 1923, with the pogrom over and the Civil War in the south almost over, he must have judged it safe to visit his family back home and did so having got authorisation for two weeks’ leave from his superiors. Unfortunately for him, the authorities had long memories and two days after his arrival back in Belfast, the RUC arrested him.

The police had been after him for some time. His arrest record reads: “Character – morally good, politically bad. Was one of the most active and dangerous characters in the City, involved in all murders and incendiary campaign. Was recommended for internment on 18-4-1922, but could not be found when his arrest was ordered in May 1922.”22

An internment order against McPeake was drawn up, directing that he be lodged on the Argenta, but it was never actually signed. Initially held in Crumlin Road gaol, he wrote to the Ministry of Home Affairs, claiming that prior to joining the Free State Army, he had been a peaceful, law-abiding citizen:

“Previous to going about twelve months ago I was Acting Secretary to a Pease [sic] Committee for St. Malachy’s district which waited on D.I. Armstrong at Chichester St. (I may call it a [deputation] from the Committee). The Rev. McKinnley of St. Malachy’s or any of the gentlemen on that deputation can certify this.”23

The authorities weren’t fooled by this. Among the documents captured in the raid on the Rathbone Street hall were some that identified McPeake as having been Adjutant of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion, along with receipts he had signed relating to the issuing and return of arms and ammunition.24

A clearly panicked McPeake then sent a telegram to the Assistant Adjutant-General of the Free State Army in Portobello Barracks in Dublin, hoping for intervention from on high: “Was on leave from Dundalk. Nothing against me. No charge. Still detained. Had an official pass.” The northern authorities were aware that McPeake was a lieutenant in the Free State Army and were concerned that this fact might prompt vigorous and unwelcome enquiries from Dublin, so on 28th March, Dawson Bates signed a conditional release order: “… do hereby prohibit the aforesaid JOSEPH McPEAKE from residing in or entering the following area, that is to say, any part of Northern Ireland outside the Rural District of Coleraine in the County of Londonderry.” Faced with a choice between internal exile to Coleraine or returning south to Dundalk, McPeake opted for the latter.25

Humiliation

A total of twenty-eight men with addresses in the Market were interned.26

Of this group, sixteen can be confirmed as IRA members from either contemporary IRA documents or the nominal rolls drawn up in the 1930s. Altogether, 728 men and women were interned between May 1922 and December 1924, so men from the Market accounted for 4% of this total.27

Internment regulations

The treatment of the internees in captivity has previously been documented by Denise Kleinrichert in her book, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922 so it is not proposed to repeat that here. Many remained incarcerated until as late as 1924, as they refused to appear before the Advisory Committee set up to review cases, make recommendations in favour of or against release and decide what conditions should be imposed in the event of release.

One of the factors dissuading internees from applying to go before the committee was a questionnaire that was put to them at the start of each appearance; they were asked, “Are you a loyal subject of His Majesty? Do you acknowledge the authority of the Government of Northern Ireland?” as well as questions relating to membership of the IRA and IRB (or Na Fianna in the case of youths, Cumann na mBan in the case of women). Given that the answers required were obvious, the questionnaire represented a form of ritual humiliation, but only having completed it would internees then be informed of the committee’s decision about whether or not to recommend release.

Summary

The application of internment in 1922 provided an early foretaste of what the future held for those who now found themselves on the wrong side of the border.

Until the internment of a small number of members of the paramilitary Ulster Protestant Association in the autumn of 1922, the power to intern was directed exclusively at members of the nationalist community.

But although the authorities wielded internment in a discriminatory manner, they made little effort to differentiate between active Republicans and innocent nationalists. Some of those interned from the Market were indeed IRA activists. However, there were others who had no Republican involvement – the seven card-players, the fathers of IRA men, and the unfortunately-named Patrick Quinn.

While all of those interned, IRA members or otherwise, were subjected to the ritual degradation involved in appearing before the Advisory Committee, the ex-soldier Daniel Flannery was the only internee from the Market who the RUC admitted to having detained in error.

In short, this clause of the Special Powers Act was applied in a one-sided fashion, indiscriminately used against the nationalist community as a whole and – with only a single exception – the authorities’ view of themselves that they could do no wrong was so entrenched that appeals to Unionist politicians to rectify obvious injustices fell on deaf ears.

This clearly indicated the nature of the partitioned state to which nationalists were now subjected.

“Pogrom and Partition – Belfast’s Market Area, 1920-22” will be launched by the Market Development Association, in conjunction with the Pangur Bán Cultural and Literary Society, on 28th October in St George’s Market, East Bridge Street, Belfast.

References

1. Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/961A.

2. Burns, James, Raphael St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1985; Delaney, William, Reilly’s Place, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1983; Dorrian, Denis, Reilly’s Place, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1984; McGurk, Peter, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1986; Murray, Peter, East St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1995. There was no regiment named “Royal Ulster Rifles” in the British Army prior to January 1921, when what had been the Royal Irish Rifles were renamed; however, Murray claimed to have left the army in December 1920.

3. Internment of John Miley, Annette St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961C; Fitzpatrick, Peter, Annette St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1991; Internment of James O’Hanlon, East Bridge St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961B; Internment of James Gray, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961D; Kelly, William, Lagan St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1992; McCann, Hiram, Lagan St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1994; Internment of John Kelly, May St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961E.

4. Military Advisor to Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, 15th August 1922, in Internment of John Miley, Annette St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961C.

5. Report by M.M. Haldane, Director, CID, 24th August 1922, in ibid.

6. William Dodds to Ministry of Home Affairs, 23rd July 1922, in ibid.

7. DI Armstrong to RUC City Commissioner, 24th July 1922, in Dodds, William, Market St, Belfast, PRONI HA/5/1989.

8. Doran, Joseph, Grace St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1869.

9. Ibid.

10. McGlade, Joseph, Walsh St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1870 & Donegan, John, Catherine St North, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1868.

11. McDonnell/McDonald, Joseph, Lagan St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1787.

12. Internment of James O’Hanlon, East Bridge St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961B; McGurk, Peter, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1986.

13. Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

14. Henry Crofton, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives, MSP34REF00106.

15. Flannery, Daniel J., Hamilton St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1540.

16. Hawkins, Joseph, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1493.

17. Northern Whig, 23rd May 1922; McStravick, James, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1494.

18. Quinn, Patrick, Cromac St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2123.

19. Connolly, Charles, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2100.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. McPeak, Joseph, Little May St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2344. It is worth noting that this report states that internment lists were drawn up in mid-April, a full month before the killing of William Twadell and prior to the internment provision of the Special Powers Act being activated.

23. Ibid.

24. Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

25. McPeak, Joseph, Little May St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2344. Nothing in McPeake’s file suggests any family connection to Coleraine. The 1911 Census shows a Joseph McPeake, then aged 9, whose mother was named Mary, living in Lissan, County Tyrone; the Free State Army Census of November 1922 recorded his age as 20 and his mother’s name as Mary, with Little May Street now the family home. The release order signed by Dawson Bates would therefore appear to be a purely spiteful updating of Oliver Cromwell’s remark: “To hell or to Coleraine.”

26. Denise Kleinrichert, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2001), pp337-368.

27. Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A; Nominal Rolls, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast), 2nd Battalion, MSPC, Military Archives, MSPC/RO/404.

-

This comment was originally posted on 18th Oct 2022 by benmadigan (themirror.wordpress.com) but was accidentally deleted when I was doing some tidying up.

Congratulations on excellent work and thorough research.best wishes for every success with your publication

LikeLike

Leave a comment