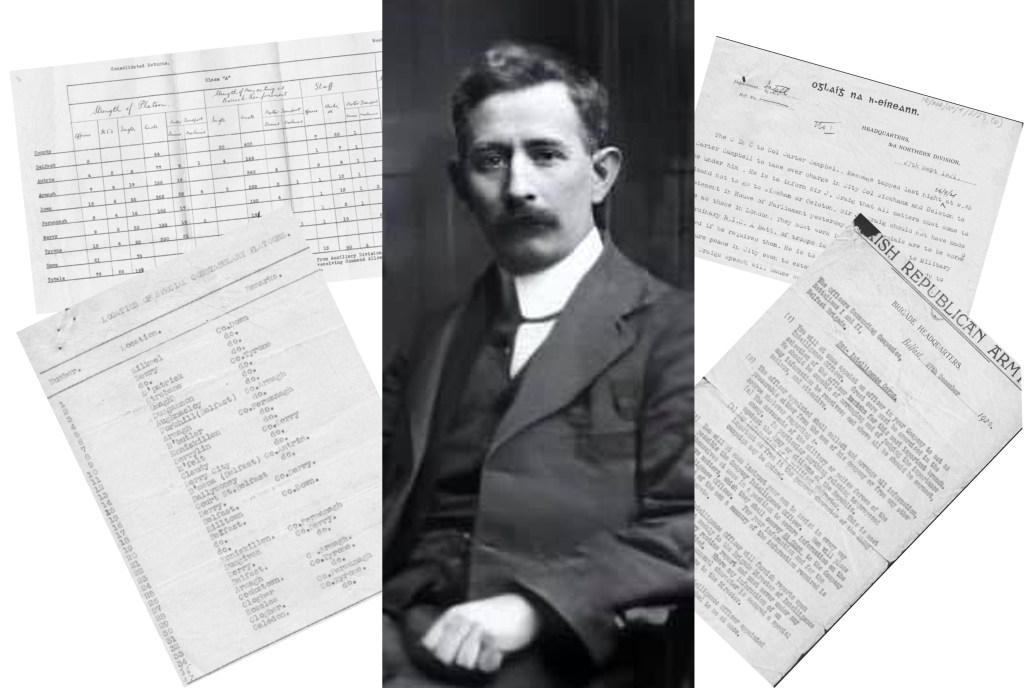

Images of documents above used with permission of Military Archives, Michael Collins Papers, CP/05/02/23

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

As Frank Crummey had a very unusual surname, there were nearly as many variations in its spelling as there were people trying to spell it. For simplicity, I have corrected all of these to the one that he used.

Early career

Frank Crummey was born in 1874 in Bessbrook, County Armagh. In the 1911 Census, he was living in Aghafatten, near Ballymena in County Antrim, with his wive and five children, working as a teacher in a national school. By 1918, he had moved to Belfast, having become headmaster of Conway Street National School No. 2 – the importance of the numerical distinction will become apparent; he was now living at 59 Raglan Street in the Lower Falls.1

According to a later police report, “he did not openly come forward until the General Election of 1918, when he then appeared on the public platform in support of Sinn Fein, denouncing constitutional methods and treating it as a humbug.”2

However, he is not named as a speaker in any press reports of Sinn Féin election rallies, although this may simply reflect media bias – for obvious reasons, the unionist newspapers gave scant coverage to Sinn Féin speeches, while the nationalist Irish News was firmly in the camp of Éamon de Valera’s electoral opponent in Belfast Falls, Joe Devlin, a former director of the paper.

Crummey joined the Irish Volunteers in December 1918, the same month as the election. He was initially a member of the Engineers Company but became Battalion Intelligence Officer (I/O) the following June, then Brigade I/O in August the same year.3

He set about establishing an intelligence network and succeeded in penetrating all parts of the British administration in Belfast: “A service was established in all government departments in the area, General Post Office, telephone exchange, police headquarters and Victoria military barracks.” A previous blog post outlined the extent to which Crummey was fed information by a network of sympathetic policemen which he created. In addition, according to another IRA veteran, David McGuinness, “In a few short months we had practically completed a copy of every important file in the Military Headquarters.”4

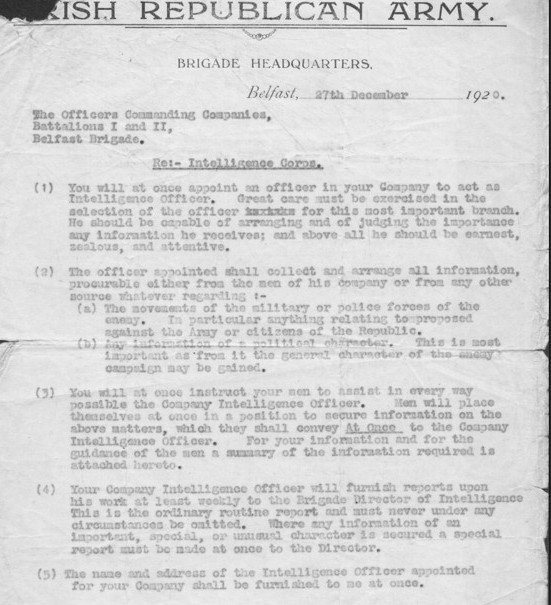

At the end of December 1920, he put in place a process whereby each company of the Belfast IRA would appoint an I/O to send him weekly reports on:

- British military: strength in each barracks, movements, numbers and types of cars, places frequented by officers of importance

- Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC): strength in each barracks, “character of men,” names, descriptions and, if possible, photos of plainclothes men; numbers and types of cars

- Special Constabulary (“Specials”), Auxiliaries, Black & Tans: names and addresses, movements

- Politicians: “All matters relating in any way to politics;” names, addresses, movements, places of business5

IRA Belfast Brigade memo establishing Crummey’s company-level intelligence structure (image used with permission of Military Archives, Michael Collins Papers, CP/05/02/23)

However, within a short time of this memo being circulated, the police became aware of Crummey’s IRA membership – they found a copy of the document on a man named Joseph Totton of the Hannahstown Company, along with an instruction from the O/C 1st Battalion, Joe McKelvey: “The enclosed instructions [sic] re intelligence work is to be acted on as soon as possible.” Most damaging to Crummey was another memo from McKelvey to Totton: “A Battalion Council meeting at which you are to attend will be held at 59 Raglan Street on Friday the 31st inst.” This was Crummey’s address and he was forced to go on the run.6

3rd Northern Division

In March 1921, as part of a new IRA policy of creating divisions, the 3rd Northern Division was formed, comprising the Belfast, Antrim and East Down Brigades. Crummey was appointed Divisional I/O, reporting to the IRA’s Director of Intelligence, Michael Colliins.

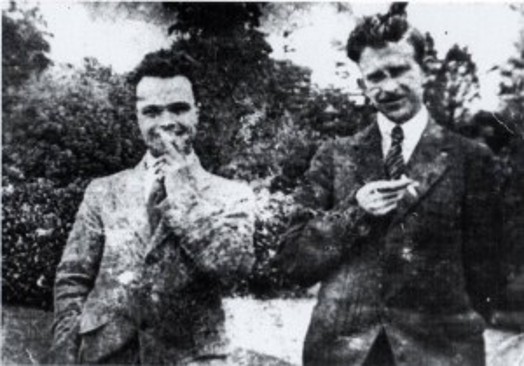

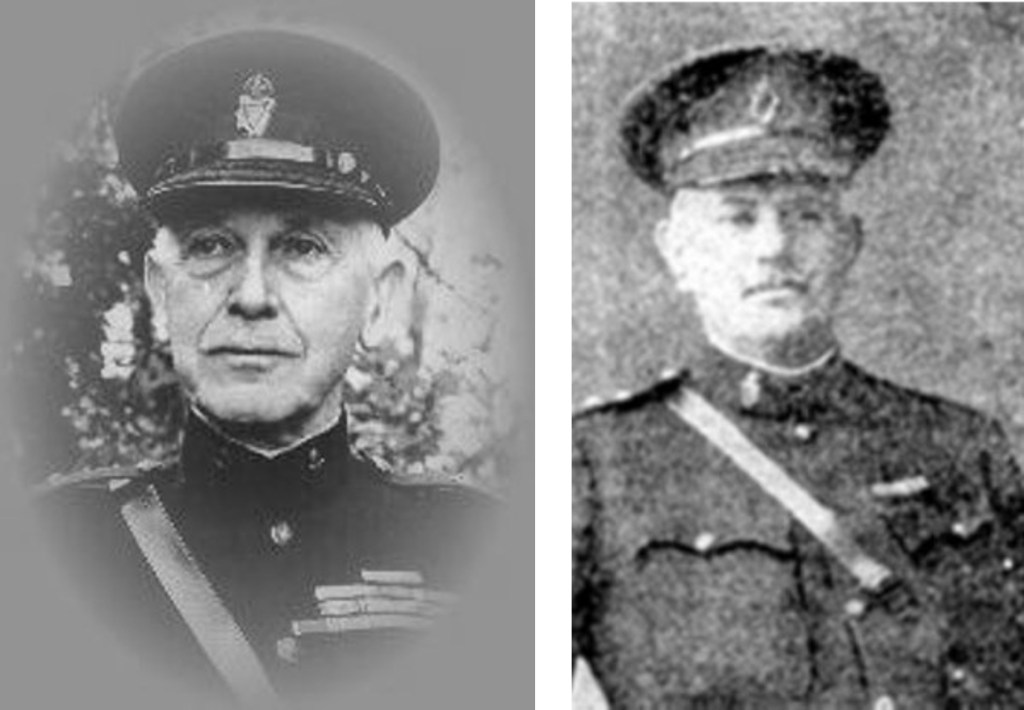

Divisional Staff of 3rd Northern Division, L-R: Séamus Woods (Adjutant), Tom McNally (Quartermaster), Joe McKelvey (O/C), Frank Crummey (Intelligence Officer)

However, this appointment was not without controversy.

Collins had intended appointing Seán Cusack to the role – Cusack had been a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in Belfast in 1914 and was O/C of the Belfast & East Down Brigade from late 1917 until the summer of 1919, when he was replaced by Seán O’Neill. After that, Cusack was mainly engaged in intelligence work, but he was captured and interned in March 1921. As a result, Crummey temporarily became Divisional I/O.7

Cusack was released from internment at the time of the Truce in July 1921 and was aggrieved when Crummey was confirmed in the role of Divisional I/O, writing angrily to Collins:

“Now Micheál I ask you, do you think it fair that after me carrying on this work (when it was not a department) … that I should be superseded in my own area by a practically unknown man in the army up to the riots of last year; and to go into a new area and do spade work there after doing spade work here since the formation of the Volunteers in 1914?”8

Cusack also complained to Eoin O’Duffy, who had been appointed Truce Liaison Officer for Ulster, and then to Collins again:

“Eoin informs me that you asked McK [McKelvey] as to the merits or demerits of Frank and myself and he vouched for the super qualities of F. as was only what I would expect under conditions existing here through the Gaynor regime (which I am happy to learn, in national interests, has ended).”9

Joe McKelvey and Eoin O’Duffy during the Truce (Irish Volunteers Commemorative Organisation)

However, despite Cusack’s protests, Crummey remained in place as Divisional I/O. He also became Assistant Truce Liaison Officer to O’Duffy.10

The Truce: more controversy

With the Truce in effect, Crummey returned to his home in Raglan Street. He also attempted to return to teaching and in doing so, sailed into another storm.

Conway Street was an important interface, running from the nationalist Falls Road to the unionist Shankill Road, bisected by Ashmore Street. The national school at which Crummey taught was under the management of Fr Charles O’Neill, parish priest of St Peter’s in the Lower Falls; although it was a Catholic school, it was situated beyond Ashmore Street and was opposite where Fifth Street is today, placing it well inside unionist territory. The reason it was designated “Conway Street National School No. 2” was that it was directly opposite the Protestant Conway Street National School.

Conway Street National School, a Protestant school opposite the Catholic school of the same name at which Crummey taught (© National Museums of Northern Ireland)

At the start of October 1921, Crummey requested police protection so that he could resume teaching at the school. It appears that the reputation of Crummey’s republican involvement had preceded him, so one day, he turned up accompanied by what appeared to be an IRA bodyguard – this had a predictable effect on Protestants living nearby and those bringing their children to the school across the street:

“Within the past few days a growing hostility was apparent and on 4th inst, Crummey, evidently thinking that the police protection was insufficient, brought four civilians with him to the school and another teacher named Joseph McLoughlin. This was observed and were it not for the police and military precautions taken, grave trouble would have ensued on 4th inst; as it was matters passed off quietly.”11

Crummey stayed away on the following day, and his assistant did likewise the day after, as there had been assaults on the teachers and children. However, Fr O’Neill was determined to open the school again on 17 October – a Head Constable of the RIC flagged the possibility that if Crummey’s school remained closed, there could be retaliatory “counterattacks on teachers and children attending the Model School.” This was a Protestant school, situated just as awkwardly as Crummey’s, on Divis Street, deep in nationalist territory.12

District Inspector (DI) J. Deignan requested a military presence at the school in the morning, at lunchtime and after school on the day of the re-opening; this, and the fact that only one lady teacher attended, meant the day passed off peacefully, but the situation was clearly untenable: “There will be no difficulty in maintaining peace if Mr Crummey stays away. From enquiries made and conversations I have had with people in the locality, he is the only person to whom exception could be taken.”13

Eventually, a request went up the police chain of command from DI Deignan, leading to a request from the Under-Secretary for Ireland in Dublin Castle to the Commissioners of National Education that Crummey be “transferred to some other school preferably in the south of Ireland.” The Commissioners replied that the appointment of teachers was a matter for the manager of each school – in other words, for Fr O’Neill.14

By the time this rejection travelled all the way back down the chain of command, DI Deignan was able to report that the problem had gone away, after a fashion. Although the lady teacher had been able to keep the school open until 23 November, it had been partly damaged in an arson attack and Fr O’Neill now had no intention of trying to re-open it. Instead, he was negotiating with the Model School for the use of some of its classrooms – so far without success.15

After an arson attack, there were attempts to relocate the Conway Street school to the Model School in Divis Street (St Comgall’s School, Facebook)

This would not be Crummey’s last brush with teaching-related controversy. But while this tempest was ebbing and flowing around him, he continued to gather intelligence.

In November, he learned of a potential new source at the heart of the RIC who might be worth recruiting as an IRA agent: “There is a Constable J. Linnane, a clerk in City Commissioner’s office here, who is reported as being a decent fellow. He is a native of Gort or Corofin. Get me some particulars about him. I’ll get one of our friends to approach him.”16

In his January 1922 report, he enclosed the rough draft of a bill that was to be put before the Northern Ireland Parliament, “It is evidently a revised version of the ROIA [Restoration of Order in Ireland Act] to suit the conditions here.” Crummey was therefore aware of the contents of what would become the Special Powers Act two months before it was presented to Unionist MPs.17

In the same report, he highlighted the RIC’s determination to incorporate loyalist paramilitaries into a new C1 Special Constabulary, despite the political embarrassment it had suffered as a result of the plan becoming public the previous November:

“Notwithstanding the withdrawal of the famous, or infamous secret circular that was exposed some time ago, recruiting has been carried on for the establishing of a new civil force under the guise of ‘C’ Class Specials. As far as Belfast is concerned, these are really the ‘Imperial Guards,’ an armed military force which has been doing all the gun work during the recent disturbances.”18

C1 Specials on Albertbridge Road

Crummey evidently had his agents everywhere. He had previously been warned by Dublin about the presence in Belfast of a British spy named Colonel Attwood, alias Major or Captain G. Dudley – he reported back: “He has a room in Ulster Reform Club. One of our men got into his room and had a search through his papers. From these I gather that he is here permanently and is organising a Secret Service for Northern Ireland.”19

In February, Crummey provided a comprehensive report on the numbers of Specials, not just in Belfast or the 3rd Northern Division area, but in Belfast and each of six counties of Northern Ireland, as well as the Specials’ training depot in Newtownards. His figures were not mere estimates, rounded to the nearest 50 or 100, but were very precise:

- The number of A Special Platoons, and the numbers of officers, Head Constables, Sergeants and Constables allocated to them; in Belfast, these were Nos. 22, 23 & 24 Platoons, with three officers and 64 Constables

- The numbers of A Specials acting as barrack reinforcements; in Belfast, 20 Sergeants and 422 Constables

- The numbers to date applying to and sworn into the B Specials; in Belfast, this was 1,795 sworn in out of 3,114 applicants

- The numbers of sworn-in C Specials; in Belfast, this was 2,177

- He highlighted that out of 78 Specials officers across the north, 25 had been “seconded from Auxiliary Division”20

He also later claimed that “One of my agents procured a secret document showing a military scheme drawn up by the late General Sir Henry Wilson. This caused a sensation when published by General Collins and was used effectively by him.”21

In a period when political and sectarian violence in Belfast was increasing enormously, Crummey’s intelligence reports were clearly invaluable to Collins in his new role of Chairman of the Provisional Government when dealing with James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, and Winson Churchill, Colonial Secretary of the British government. This was demonstrated when Collins brought Crummey to London with him for tripartite discussions that led to the second Craig-Collins Pact, signed on 30 March.22

Crummey (R) accompanied Michael Collins to the talks in London which led to the second Craig-Collins Pact (photo courtesy of Pádraig Crummey)

“Special intelligence work” for Collins

The Treaty and the political situation in the north in early 1922 led to the formation of several committees, and more were to follow in the wake of the Pact.

A meeting of northern delegates to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis on 22 February agreed to form an Advisory Committee, reporting to the party’s executive. This Sinn Féin Advisory Committee was dominated by anti-Treaty figures, with Michael Carolan acting as its secretary. It first met in St Mary’s Hall later that month and then in Derry in early April; by May, its executive had decided, “That the secretary be instructed to convene a meeting of the whole Advisory Committee for the purpose of devising a definite plan of campaign to be adopted by the nationalists of the north east whereby they can render impotent the so-called Government of Northern Ireland.”23

On 8 March, the Provisional Government decided to establish its own North East Advisory Committee, although the first meeting was not convened until 11 April.

This was a massive gathering, with 51 attendees. All the members of the Provisional Government were there, as well as several other non-cabinet TDs. For the IRA, Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy attended, along with Séamus Woods (replacing the original invitee, McKelvey) and Crummey from the 3rd Northern Division, Seán O’Neill of the Belfast Brigade, as well as Tom Morris and Donal McConnell from the 2nd Northern; Frank Aiken of the 4th Northern was invited but did not attend. Dr Henry Russell MacNabb had a foot in both camps, military and political: he had been a member of the GPO garrison in the 1916 Easter Rising and was the Medical Officer of the 3rd Northern Division; he was also a leading member of Sinn Féin in the city. Also representing Sinn Féin were the secretary of its Belfast Executive, Sam Heron, and Frank McArdle, as well as 17 other prominent party members from elsewhere in the north; during the meeting, it emerged that some of these were also members of the Sinn Féin Advisory Committee, referred to as “de Valera’s Committee.” Joseph MacRory, Bishop of Down & Connor was there, as well as two other bishops and ten priests.24

As well as large, the meeting was lengthy – the minutes ran to 59 typewritten pages. Crummey only spoke on a few occasions.

Most of the discussion revolved around the Pact: its opening clause, “Peace is today declared” had been shown to be wildly optimistic by the Arnon Street killings of 1 April. Collins had demanded a public enquiry into the killings, a proposal which Craig rebuffed – as a result, implementation of most of the Pact was delayed.

One of its most significant provisions, and one that was controversial on both sides, was that Catholics would be recruited to the Specials in Belfast: “Special Police in mixed districts to be composed half of Catholics and half of Protestants, special arrangements to be made where Catholics or Protestants are living in other districts. All Specials not required for this force to be withdrawn to their homes and their arms handed in. (emphasis in original)” To facilitate this, a Catholic Recruiting Committee, nominated by Collins, was to be formed.25

“Peace is today declared:” One of the most controversial clauses in the second Craig-Collins Pact was one providing for recruitment of Catholics to the Specials in Belfast

MacNabb told the meeting that “There is going to be a manifesto issued [by Belfast Sinn Féin] from the chapel doors next Sunday, saying that any man having anything to do with the Specials should be shot at sight.” Heron disagreed, saying the manifesto was only meant as propaganda: “It does not say they should be shot at sight, but it certainly denounces any Catholic who joins the police.”26

In response, Crummey was contemptuously dismissive of Belfast Sinn Féin members, characterising many of them as mere fair-weather latecomers:

“I wonder how many of those people who drew up that manifesto will be in the firing line? Those Sinn Féin Clubs have all been set up since the Truce. It was a dangerous thing to be part of it during the war. But when the Treaty to which a good many of them are objecting, as well as they are objecting to this Pact – when the Treaty enabled them to become members of Sinn Féin Clubs, there were twelve Sinn Féin Clubs started and now they are out to die in the last ditch.”27

Nor did he hold the anti-Treaty IRA in high regard:

“As some of our friends don’t intend to carry out the Treaty I think that suggestion of his lordship Dr MacRory should be carried, and that is that we should try to get as much out of it [the Pact] as possible, and let it break, and let the people who are anxious for war get as much out of it as possible. It is going to be broken by our friends or enemies.”28

In relation to the Catholic Recruiting Committee, Crummey asked “Have they asked for any Catholics to go down and hand in their names?” Collins said he had the names but had not passed them to Craig, pending resolution of the Arnon Street inquiry debacle.29

He finally gave Craig the list of his nominees on 25 April: it included Bishop MacRory and two priests; MacNabb and McArdle from Sinn Féin, as well as Alderman John Harkin, a Nationalist Party councillor who was open to co-operation with Sinn Féin, and several Devlinite businessmen; Crummey and Daniel Dempsey, an intelligence officer of the Belfast Brigade, were Collins’ IRA nominees. The RIC, as noted above, were already aware of Crummey’s IRA membership, although not his rank or intelligence role.30

On 15 May, there was a follow-up meeting in Belfast of northern members of the Provisional Government’s North East Advisory Committee, minus the clergymen and with fewer Sinn Féin delegates.

Crummey informed this meeting that he and MacNabb had met Collins on 9 May. Collins now wanted Crummey to act as the initial point of contact for all reports of Specials attacks, raids and harassment, funnelling these into daily reports to the Dáil Publicity Department in Dublin as well as providing Collins with summaries three times a week.31

MacNabb bemoaned the extent to which pro-Treaty elements in Belfast Sinn Féin were being caught in a pincer movement:

“Our difficulties are very great in Belfast. There are two sets of people who want to work the Pact and interpret it in their own way – the de Valera people and the Devlinites. The de Valera section come up and shoot two or three people in certain areas. They then expect the priests to rush in to the northern government for protection after the other side have shot enough. They go down and offer to set up 50 Specials in that particular area and it comes before the Catholic Protection Association [sic – Committee]. They then say it’s time the Provisional Government would take some interest in the Catholics here and that they are doing nothing for them.”32

The meeting concluded on a belligerent note: “The following was agreed to: Recommend an active destruction policy inside the Six-County area apart from the border; the destruction of roads, bridges, etc and other ways in which we could make government impossible in the Six-County area.”33

Woods, O’Neill and Crummey were joined at the meeting by William Lynn, a battalion commander in the Antrim IRA; these IRA officers refrained from informing their Sinn Féin colleagues that just such a destruction policy was due to begin in three days’ time, with the launch of the IRA’s “northern offensive.”

In his later application for a Military Service Pension, Crummey stated that he relinquished his role as I/O of the 3rd Northern Division at this time: “Acting on request of late General Collins, relieved from duty from 1st May 1922 to act as secretary to a North East Advisory Committee and to act as publicity agent for the North East.” He was replaced as Divisional I/O by McGuinness, who had, up until then, been Crummey’s successor as Belfast Brigade I/O.34

According to Crummey,

“In May 1922 I was instructed by General Collins to open an office in Belfast, buy a typewriter, employ a typist and act as publicity agent. As it was unsafe to open an office, which would have been immediately raided and closed, I used the office of the Catholic Protection Committee, which was tolerated, placed two of my men in it and used the typist for my purpose thus saving expense and securing immunity from annoyance by the government (northern) at this time.”35

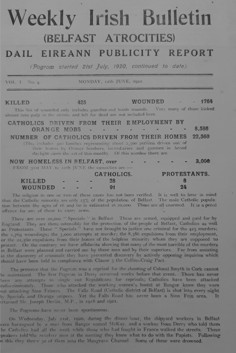

Beginning on 22 May, the Dáil relaunched the Weekly Irish Bulletin it had published during the War of Independence, except it was now titled Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities). Crummey’s reports were central to this publication.36

The concluding decision of the second North East Advisory Committee meeting and his knowledge of the impending “northern offensive” undoubtedly coloured Crummey’s approach to the Catholic Recruiting Committee when it met for the first time on 16 May.

Crummey’s reports formed the basis of the Dáil’s Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities) (© National Archives of Ireland, TSCH/3/S10557 Weekly Irish Bulletin)

He was not the only one to attend that meeting in bad faith. A month beforehand, on 18 April, Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood, Craig’s Military Adviser, had told the cabinet, “The enrolment of Roman Catholic B Specials in any other district [than Catholic ones] is open to very grave dangers, and the enrolment of any RC [Roman Catholic] A Specials except through the present channels might lead to the disorganisation of this force.”37

The government decided to simply ignore the provision for half-and-half patrols of Specials in mixed areas that had been stipulated in the Pact signed by Craig less than three weeks previously:

“It is only intended that Roman Catholic ‘B’ Special Constabulary should be raised for duty in the Roman Catholic areas in Belfast. The question of taking RC A Specials – except through the present channels – does not arise at the moment, but if the RC B recruiting agency proves a success, it would be possible to accept A Specials through this source in the same way as through other B Special Constabulary channels and with the same safeguards. There is no question of suspending recruitment of A Specials in order to ensure any fixed proportion of Roman Catholics.”38

Bishop McCrory, McArdle and Dempsey did not attend the meeting. Representing the government were Solly-Flood; RIC Divisional Commissioner Charles Wickham and Belfast City Commissioner John Gelston; and Samuel Watt, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Ministry of Home Affairs.

After an opening preamble by Solly-Flood, who stressed he was keen for the committee to propose names of potential Catholic recruits to the Specials as soon as possible, Crummey “pressed for a statement showing the numbers of Special Constabulary and inquired whether the existing Constabulary would be sent to their homes in accordance with the terms of the agreement.” Solly-Flood declined to provide the numbers. Gelston assured the committee that only Catholic B Specials would be used to patrol the Falls Road area.39

No progress was made in terms of recruiting Catholics to join the Specials (© National Museums of Northern Ireland)

Crummey and MacNabb were the most vocal of Collins’ nominees at the meeting and both pressed for a commitment that a third of all Specials would be Catholics. Fr Laverty set the cat among the pigeons when he said he assumed they would be recruiting for all classes of Special Constabulary, As, Bs and Cs. Here, Watt provided an administrative pretext for putting into effect the previous government decision that there would be no Catholic Specials other than Bs: he pointed out that there was an established practice whereby police were not allowed to serve in their home districts and Wickham said this rule applied equally to A Specials.40

MacNabb argued that this undercut the whole objective of the Pact which was to encourage Belfast Catholics to join the Specials to ensure peace in Belfast. Wickham offered an olive branch and suggested that a quota of Catholic B Specials could be allocated to police Catholic areas, but MacNabb pressed for a third of all Specials to be Catholics and Crummey asked again for the current numbers of A, B and C Specials and how many Catholics would be required.41

After some inconclusive discussion, Crummey returned to his primary purpose, which was to gather intelligence rather than recruit Catholics, and asked for a third time how many Specials there were in each class. For a third time, he got no answer. The meeting ended with Collins’ nominees agreeing to consider Wickham’s proposal and return for another meeting.42

RIC Divisional Commissioner Charles Wickham and Belfast City Commissioner John Gelston distrusted Crummey’s involvement in the Catholic Recruiting Committee

In the aftermath of the meeting, Dempsey was arrested on 22 May; the following day, the northern government introduced internment in response to the killing of Unionist MP William Twadell. Bearing in mind these two developments, the decision of Crummey to attend the second meeting of the committee on 31 May was perhaps rash and foolhardy. At that meeting,

“Solly-Flood began brusquely. ‘I do not propose to waste one single moment … in discussion of any kind, shape or form,’ he said. He refused to give any information on the overall size of the USC, refused to accept the principle that one-third of the force should be Catholic – though Craig had specifically conceded this in London – and repeated that they could only recruit B Specials. ‘Now that is how the matter stands and that is the only basis of discussion that I can permit this afternoon,’ he concluded.”43

According to the Minister for Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates, the government representatives suggested to the nationalists that, “they might endeavour to secure Roman Catholic recruits from the country, who might be trained and then serve as A Specials in the city of Belfast.” They agreed to discuss this suggestion and give their response at the next meeting.44

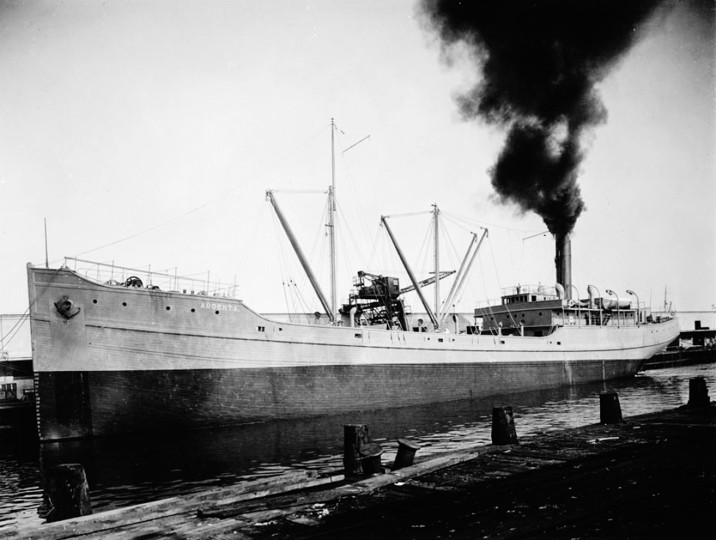

But that night, Crummey paid the price for his folly in attending the meeting: he was arrested, held for four weeks in Crumlin Road Gaol, then interned on the prison ship SS Argenta on 30 June.

Internment

By the end of August, there were 235 IRA internees from across the north on the Argenta, along with 104 civilians. By then, the Civil War in the south was two months old and the divisions over the Treaty which had led to the war were also reflected in how the internees on the ship organised themselves. There were two separate Army Councils on board, one for the 184 pro-GHQ IRA internees and a separate one for the 28 anti-Treaty and 23 neutral members of the IRA. However, in order to present a united front when dealing with the prison regime on behalf of both sets of IRA internees as well as the purely political prisoners, there was also a General Council for all internees, led by James Mayne, a solicitor’s clerk from Cookstown, County Tyrone.45

The internment ship SS Argenta

The pro-GHQ Army Council consisted of all officers who had held battalion rank or higher on the date of their arrest. Despite his having stepped down as 3rd Northern I/O at the beginning of May, Crummey availed of his recent rank to take a place on the council.46

In the initial stages of internment, in line with a broader policy of non-recognition of the Government of Northern Ireland, the prisoners adopted a policy of non-recognition of the Advisory Committee, a body established by the northern government to hear internees’ requests for release. However, some did apply to go before the Advisory Committee and as a result, were ostracised by their fellow-internees then transferred to Larne Internment Camp.47

The question of whether to apply to the Advisory Committee would lead to the next bout of controversy to engulf the former Conway Street teacher.

On 6 January 1923, acting on Crummey’s claim to have received advice to do so from Eoin MacNeill, the Free State Minister for Education, he and six other teachers on the Argenta applied to be heard by the Advisory Committee. Mayne immediately called a mass meeting of all internees on board, which became stormy from the outset. Crummey said of Mayne, “He practically accused me of making the story [up] and pointed to the want of documentary evidence. He finished up a flag-waving and sunbursting oration by calling all the men on the ship to ostracise us.”48

Faced with their fellow-prisoners’ intense opposition, five of the teachers withdrew their applications, leaving only Crummey and Philip Ryan, another member of the Belfast IRA. In describing this turn of events, Crummey managed to disparage the manhood of an entire county: “the three who belonged to the Army Council alleging their reason for doing so was because the Army Council disapproved and two other elderly men withdrew because being Tyrone men they could not go on after the others backed out.”49

Although the mass meeting had been held with prison warders present to note what was being said, the authorities still managed to misread the situation. On 9 January, Crummey was ordered to be transferred to Larne to have his appeal heard by the Advisory Committee, but Captain J.E. Lang, Deputy Governor of the Argenta felt he would fight the decision as he was “getting on so well with his work of organising the disturbing element on board that he does not wish, under any consideration, to be moved to Larne.” In the event, Crummey’s transfer went ahead the following day without any protest by him.50

He appeared before the Advisory Committee on 17 January. Uniquely among all the internees whose cases I have studied, we have both the Ministry of Home Affairs’ summary of the interview and a longer account written by the internee himself; these two versions of the Crummey interview are consistent with each other.

The interview took the form of a series of questions, to which it was blindingly obvious what constituted the only acceptable answer.

The first question was “Are you a loyal subject of His Majesty?” The internee was clearly meant to answer “Yes” but Crummey’s response was less straightforward:

“Up to the 11th July 1921, I certainly was not loyal to King George. From July 1921 to December 6th 1921 I could not say I was loyal, but I could not be called disloyal. Since ratification of the Treaty of which I am a firm supporter, I can say that I am, under the altered conditions which now exist as a result of the Treaty, loyal to King George.”51

The next question was “Do you acknowledge the authority of the Government of Northern Ireland?” and the expected answer was simply “Yes” but again, Crummey’s answer was more convoluted: “Same answer as I gave to last question can be made in this case. I couldn’t say I was loyal but now that Six Counties has opted out under the Treaty, as a supporter of the Treaty I am loyal to northern government.”52

When the committee asked, “Are you a member of the Irish Republican Army?” the internee was obviously meant to deny that he was, but Crummey once more gave a more protracted answer:

“Up to March 31st 1922 I was a member of IRA. On that date a treaty was signed on behalf of Six County government by Sir James Craig and by Provisional Government represented by General Collins, setting up certain machinery to restore order in Six Counties and Belfast. From that date I was not an active member of IRA as all my energies were devoted to trying honestly to have articles of treaty carried out.”53

Probing his evasion, the committee then asked, “Are you now a member of IRA?” and Crummey denied that the organisation still existed:

“As a matter of fact there is no such body now. What was the IRA has been merged into the National Army. Men who lived in Six County area have either gone across the border and are now engaged in the National Army or have dropped out of existence. No army connected with the National Army exists at present in Six Counties.”54

Despite Crummey’s efforts to explain himself, the Advisory Committee decided not to recommend his release. The police were even more dubious of Crummey’s protestations of new-found loyalty:

“Crummey is a shrewd man, good organiser, deep and vindictive, and is looked upon as a very dangerous man. I do not believe he has severed his connection with the IRA. He may possibly like the Free State, but I am positive he detests the northern government, and from what is known of past history apart from suspicion, the police believe he would never be loyal to it, and were he released he would be as bad as ever.”55

He was transferred to Derry Gaol on 30 January. There, because he had “acted in a manner prejudicial to the order and discipline of said place of internment [Larne],” Dawson Bates invoked a further provision of the Special Powers Act to order a withdrawal of all Crummey’s privileges: no smoking, a restricted diet, no books or newspapers, confinement to his cell apart from two hours’ exercise each day and no parcels or letters. However, after Crummey protested, his privileges were restored on 8 March.56

After rejection of his appeal for release, Crummey was transferred to Derry Gaol

Intercession from on high

While Crummey was interned, various figures on the outside were trying to secure his release.

After the unsuccessful appeal to the Advisory Committee, W.T. Cosgrave, President of the Free State Executive Council, had written to the northern Minister of Education, Lord Londonderry, telling him that Crummey had been offered a teaching job in Dublin and asking him, “to take up this particular case and effect Mr Crummey’s release.”57

W.T. Cosgrave, President of the Free State Executive Council, tried to secure Crummey’s release from internment

On 10 March, Raymond Burke, a prominent Catholic businessman closely associated with Devlin, the Nationalist Party MP at Westminster, wrote on Crummey’s behalf to Major E.W. Shewell, the Inspector of Prisons at the Ministry of Home Affairs:

“The assistant Legal Advisor of the southern government … asked me to see you in reference to this gentleman and if you can see your way to release Healey [sic – Cahir Healy] and himself I think it would do good. I understand they have instructions from the Minister of Education, Southern Ireland to give you every guarantee you require.”58

On 26 March, the southern Ministry of Education wrote to Crummey, advising him that they would keep a teaching position in Dublin open for him. This letter was intercepted by the censor at Derry Gaol.59

These representations set in motion a rapid sequence of events. At the end of March, Major Shewell asked the police for their views on a potential release for Crummey. Gelston could not wait to get rid of him: “If this man leaves the northern area we are better without him.” Wickham was equally adamant: “It is thought he ought not to be allowed at large in Belfast even for a week.”60

Crummey appeared before the Advisory Committee again on 19 April and agreed to being excluded from the north if that was what it took to be released. On 20 April, Dawson Bates ordered his release, with Crummey prohibited from entering or residing in Belfast, Antrim or Down.61

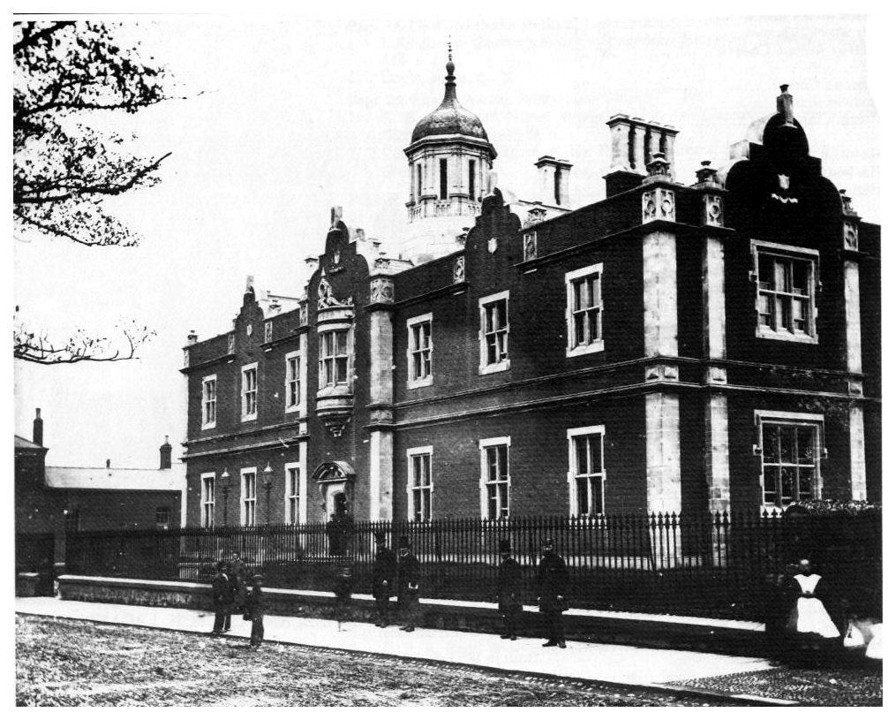

On 24 April, he was escorted to the border and released into exile. At the end of May, he took up the teaching position in Marlborough Street in central Dublin that had been kept open for him. In an ironical twist, considering the partial demise of his old school in Conway Street, his new job was in the Central Boys’ Model School.62

The Central Boys’ Model School in Dublin, (© National Inventory of Architectural Heritage)

Twilight

Crummey applied for a Military Service Pension in late February 1925, giving details of the roles and responsibilities he had held in the Belfast Brigade and 3rd Northern Division.

In accordance with the process for evaluating applications, the Army Pensions Board wrote to various individuals who Crummey had nominated to provide references. Their responses suggest that Crummey was not particularly warmly remembered by his former fellow-officers.

Séamus Woods said only that “He was a useful I/O and when on special intelligence work during Truce (August ’21) was arrested and spent a period in prison.” Crummey did not mention this arrest in his own application, nor is there any reference to it in his internment file.63

Roger McCorley was one of the main go-to men as regards references for former Belfast Brigade members; as a former Brigade O/C, he had an encyclopaedic memory of events in the city and who had been involved and to what extent. However, when it came to Crummey, he was brutally dismissive: “This man was attached to IRA and Fianna from a very early date but I am unable to give details of his service.”64

Tom McNally had been on the divisional staff of the 3rd Northern at the same time as Crummey and he was as curt as McCorley had been: “I remember this young man, he was an earnest Volunteer but I cannot remember anything in which he was actively engaged upon.”65

However, there is a caveat to these less than stellar references in that they may have thought they were being asked about Frank Crummey Junior – Crummey’s son had been an IRA Volunteer and also applied for a pension in 1925; the handwritten request for references sent from the Military Service Pensions Board of Assessors could be read as referring to either Crummey Snr or Crummey Jnr. Frank Crummey Junior had indeed been arrested in August 1921, which would explain Woods’ comment.66

McNally’s actual recollection of Crummey was probably closer to the one he gave when he was interviewed by Ernie O’Malley in the 1940s: “Intelligence: Frank Crummey was in charge of it. Old Frank was good but Donegan second in command was in charge. He got a lot of information from inside the RIC (they would have been mostly from outside Ulster and Catholic).”67

Crummey’s pension application was rejected in March 1927, so he appealed. This time he had more enthusiastic support from former officers. When Woods replaced McKelvey as O/C of 3rd Northern in April 1922, he in turn was replaced as Divisional Adjutant by Séamus McGoran, who said of Crummey: “Through the activity of this intelligence system many successful operations were carried out against police and military … He was one of the most energetic officers in the north, and as stated, prepared the groundwork for everything carried out.”68

Crummey after he had moved to Dublin (photo courtesy of Pádraig Crummey)

The most effusive praise of all came from Seán O’Neill, McCorley’s predecessor as O/C Belfast Brigade; he said:

“Considering that this applicant was a married man with a family of at least eight, all of whom with the exception of two were fully dependent on him, that he kept his home at our disposal at all times, carried out the duties of Intelligence Officer in an effective manner, gave his assistance to the political as well as the Volunteer side of the movement and enrolled four of his sons in the movement, I feel it my duty to fully recommend him to the Board as an exemplary member of the IRA.”69

O’Neill’s glowing reference was actually dated four days after the Board of Assessors decided to allow Crummey’s appeal – on 26 July 1927, he was granted the rank of Commandant for pension purposes, with IRA service recognised from October 1920.

However, he did not enjoy the benefits of his pension for long – he died, aged 52, less than three months after its award, on 20 October 1927.

Summary and conclusions

Even Crummey’s enemies in the police acknowledged that he was shrewd and well-organised. It was these qualities that helped him become a superbly capable and effective Intelligence Officer, first for the Belfast Brigade, then for the 3rd Northern Division.

He established a network of sources that fed the IRA a constant stream of vital information from inside both the police and the British military; getting one of his men to rifle through the papers of a putative British spy in the latter’s own bedroom was a particular coup.

He had clearly established his credentials with Collins prior to the signing of the Treaty, and it was in early 1922 that Crummey really came into his own as one of Collins’ most important contacts in Belfast. Collins had sent his cousin, Patrick O’Driscoll, to Belfast in March 1922 to act as an investigator for the Provisional Government and Crummey inherited that role later in the spring after O’Driscoll had returned to Cork.

By that stage, Crummey was no longer simply gathering military intelligence for the IRA but also gathering information that provided Collins with important political capital when negotiating with Craig and Churchill. Collins’ decision to bring Crummey with him to the talks which led to the second Craig-Collins Pact speaks volumes about the centrality of Crummey’s role and Collins’ dependence on him. This is amplified by Crummey’s selection to be the Belfast secretary of the North East Advisory Committee and his appointment to what was in effect the editorship of the Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities).

However, Collins’ nomination of Crummey to the Catholic Recruiting Committee was probably the move that sent his protégé flying too close to the sun. But equally, Crummey’s acceptance of the nomination suggests a sense of hubris on his part.

His house in Raglan Street was undoubtedly raided following the capture of McKelvey’s note summoning a Battalion Council meeting to be held at Crummey’s address; Crummey went on the run. So not alone did the RIC know that Crummey was involved in the IRA, he knew that they knew.

Despite this, and despite Dempsey’s arrest, Crummey attended the first two meetings of the committee and at the first one, still wearing his recent Divisional I/O hat, persisted in pressing Solly-Flood and the two most senior policemen in Northern Ireland to reveal the Specials’ order of battle. An Intelligence Officer as gifted as him should have realised they were never likely to oblige. But Crummey was now used to being close to the seat of power, although that was in relationship to the Provisional Government – did this breed in him a misplaced sense of immunity when it came to sitting opposite the Government of Northern Ireland?

If so, he was soon disabused of any such notions by his arrest on the night of the second meeting and his subsequent internment.

It is interesting that two of the most controversial episodes in Crummey’s career related to his teaching profession. His insistence on returning to teach at Conway Street National School in the autumn of 1921 backfired, as it simply emphasised his standing in the IRA in the eyes of the RIC. But teaching offered him the opportunity to secure a release from internment in the spring of 1923.

That release can be viewed in two ways.

One is that he selfishly and eagerly used Cosgrave’s intercession with Lord Londonderry to wriggle free, leaving his fellow internees behind to cling to their principled refusal to recognise the Advisory Committee. An argument against that view would be that the southern government had already decided to recognise Craig’s government in the autumn of 1922, but that the internees had not yet caught up with the new political reality and in any event, as the rest of 1923 and 1924 unfolded, many of them also decided to abase themselves in front of the hated Advisory Committee and secured their own releases, just as Crummey had done.

The alternative reading is that the route to freedom availed of by Crummey was simply not open to the majority of internees. It is notable that Cosgrave appealed to Lord Londonderry, the Minister of Education, not to Craig or Dawson Bates; the latter tended to remain steadfastly deaf to all appeals for internees’ release, even those coming from Unionist Party MPs in respect of interned loyalist paramilitaries. Only seven teachers could point to the possibility of securing teaching jobs in the south, so Crummey would have been a fool not to use this opportunity to get out of Derry Gaol. An argument against this would be that five of the seven changed their minds, although admittedly only after pressure had been applied on them by the other internees, so why did Crummey not?

Whichever of these interpretations one prefers, it is clear that Crummey acted in his own best interest. Having already sacrificed his teaching career in the north to the national interest, he may well have felt justified in doing so.

There is a postscript: after being damaged by fire in November 1921, Crummey’s old school in Conway Street eventually re-opened. However, during renewed sectarian rioting in July 1935, it was completely burned to the ground. In Belfast, nothing had changed.70

I am very grateful to Pádraig Crummey for sharing some of the photos used in this article.

References

1 1911 Census, National Archives of Ireland (NAI) https://nationalarchives.ie/collections/search-the-census/census-record/#census_year=1911&surname__icontains=crummey&county=Antrim&id=876391 (only 23 people in the whole of Ireland had the surname Crummey); 1918 Belfast Street Directory https://www.lennonwylie.co.uk/ccomplete1918_b.htm

2 City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 5 February 1923, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

3 Francis Crummey application form, 24 February 1925, Military Archives (MA), Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

4 Affidavit of Francis Crummey, 7 July 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr; David McGuinness statement, MA, Bureau of Military History, WS0417.

5 Brigade O/C to O/Cs Companies, 1st & 2nd Battalions, Belfast Brigade, 27 December 1920, MA, Collins Papers (CP), CP/05/02/23 Correspondence between Intelligence Officer 3 Northern Division & Intelligence Staff, GHQ (hereafter Intelligence correspondence).

6 O/C 1st Battalion to O/C Hannahstown Company, 29 December 1920, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey, schoolteacher and member of IRA, from Conway Street National School, Belfast.

7 Seán Cusack application form, 7 April 1924, MA, MSPC, 24SP308 Seán Cusack; Seán O’Neill application form, 16 February 1925, MA, MSPC, 24SP12109 Seán Padraig O’Neill.

8 Seán Cusack to Michael Collins, 17 July 1921, MA, CP, CP/05/02/23 Intelligence correspondence. The correspondence between Cusack and Collins uses the former’s nom de guerre, “Seán Cummins.”

9 Seán Cusack to Eoin O’Duffy, 28 July 1921 & Seán Cusack to Michael Collins, 29 July 1921, MA, CP/05/02/23 Intelligence correspondence.

10 Affidavit of Francis Crummey, 7 July 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

11 District Inspector (DI) J. Deignan to City Commissioner, RIC, 6 October 1921, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey, schoolteacher and member of IRA, from Conway Street National School, Belfast (hereafter Transfer of Francis Crummey).

12 Head Constable M.M. Murphy to DI J. Deignan, 15 October 1921, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey.

13 Sergeant F. Condy to DI J. Deignan, 17 October 1921, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey.

14 Under-Secretary to Commissioners of National Education, 4 November 1921 & Commissioners of Education to Under-Secretary, 19 December 1921, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey.

15 DI J. Deignan to City Commissioner, RIC, 14 January 1921, PRONI, HA/5/827 Transfer of Francis Crummey.

16 Divisional I/O to Deputy Director of Intelligence, 11 November 1921, MA, CP/05/02/23 Intelligence correspondence.

17 Divisional I/O to Deputy Director of Intelligence, 24 January 1922, MA, CP/05/02/23 Intelligence correspondence.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Return of strength week ending 11 February 1922, MA, CP/05/02/23 Intelligence correspondence.

21 Affidavit of Francis Crummey, 7 July 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

22 Francis Crummey to Minister for Defence, 4 May 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

23 Minutes of meeting of Northern Advisory Committee and Provisional Government, 11 April 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1011 North East Advisory Committee; Michael Carolan to Desmond Crean, 13 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/625 Prosecution of Desmond Crean, Chief St and Claremont St, Belfast, for possession of arms, ammunition and documents.

24 Minutes of meeting of Northern Advisory Committee and Provisional Government, 11 April 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1011 North East Advisory Committee; MA, MSPC, 24SP12908 Henry MacNabb.

25 Heads of Agreement between the Provisional Government and the Government of Northern Ireland, 30 March 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1801A Boundary Commission, Extracts from Statutory Declarations.

26 Minutes of meeting of Northern Advisory Committee and Provisional Government, 11 April 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1011 North East Advisory Committee.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Chairman of Provisional Government to Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 25 April 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1801A Boundary Commission, Extracts from Statutory Declarations. For Dempsey’s intelligence role in the IRA, see MA, MSPC, DP9279 Daniel Dempsey (2RB4126).

31 Minutes of meeting of Ulster Advisory Sub-Committee, 15 May 1922, NAI, TSCH/3/S1011 North East Advisory Committee.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Frank Crummey application form, 24 February 1925, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.; Séamus Woods to Board of Assessors, 26 August 1926, MA, MSPC, 24SP12764 David McGuinness.

35 Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001), p250. McDermott’s reference is to “Frank Crummey pension application, 13 April 1927, kindly lent by his nephew Patrick;” this document is not contained in Crummey’s MSPC file as released by Military Archives. Pádraig Crummey, Crummey’s grandnephew, has clarified that he possesses two letters of appeal written by Crummey: one addressed to the Military Service Pensions Board, dated 13 April 1927, and one addressed to the Minister for Defence, dated 4 May 1927; the grounds for appeal differ between the two (Pádraig Crummey email 24 January 2026).

36 NAI, TSCH/3/S10557 Weekly Irish Bulletin.

37 Military Adviser to Cabinet, 18 April 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/40 Cabinet meeting 19 April 1922.

38 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 19 April 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/40 Cabinet meeting 19 April 1922.

39 Minutes of Belfast Catholic Recruiting Committee meeting, 16 May 1922, The National Archives (UK) CO 906/23 Comments and correspondence relating to the several clauses of the Agreement signed by the Provisional Government and the Government of Northern Ireland, 30 March 1922.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), pp148-149. The minutes of the 31 May meeting are not included in either of the PRONI files where they might be expected to be found: HA/32/1/142 Formation of Roman Catholic Recruiting Committee to encourage Roman Catholics to join RUC, which only contains the minutes of the 7 June meeting, or HA/32/1/173 Visit of S.G. Tallents to enquire into and report on extent of implementation of agreement signed in London, which only contains the minutes of the 16 May meeting. The National Archives in London have also been unable to locate a copy of the minutes of the 31 May meeting in the file referenced at note 39 above.

44 Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, 10 June 1922, PRONI, HA/32/1/142 Formation of Roman Catholic Recruiting Committee to encourage Roman Catholics to join RUC.

45 Seán Sheehan, Adjutant, GHQ Army Council, SS Argenta, to Chief of Staff, 26 August 1922, MA, Department of Defence A Series (DODAS), DOD/A/07586 SS Argenta position of prisoners on board.

46 Ibid. Crummey co-signed the original handwritten version of this memo, along with Sheehan and three others, but for their own security, all the signatures were then scratched out and only the signatories’ ranks left visible.

47 James Mayne, General Council, SS Argenta, to Chief of Staff, 13 January 1923, MA, DODAS, DOD/A/07586 SS Argenta position of prisoners on board.

48 Frank Crummey to Frank O’Duffy, Secretary, Ministry of Education (Free State), 25 January 1923, MA, DODAS, DOD/A/07586 SS Argenta position of prisoners on board.

49 Ibid.

50 Deputy Governor, SS Argenta to Governor, Larne Internment Camp, 9 January 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

51 Frank Crummey to Frank O’Duffy, Secretary, Ministry of Education (Free State), 25 January 1923, MA, DODAS, DOD/A/07586 SS Argenta position of prisoners on board.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 5 February 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

56 Orders of Minister of Home Affairs, 30 January & 8 March 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

57 President of Executive Council to Minister of Education, n.d., PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

58 Raymond Burke to Ministry of Home Affairs, 10 March 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

59 Frank O’Duffy, Secretary, Ministry of Education (Free State) to Francis Crummey, 26 March, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

60 City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 3 April 1923 & Inspector General to Ministry of Home Affairs, 4 April 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

61 Order of Minister of Home Affairs, 24 April 1923, PRONI, HA/5/1791 Crummey, Francis, Raglan St, Belfast.

62 Office of National Education to Army Pensions Branch, 4 October 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr. (24C160).

63 Séamus Woods to Board of Assessors, 5 December 1925, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

64 Roger McCorley to Board of Assessors, 7 June 1926, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

65 Tom McNally to Board of Assessors, 11 September 1926, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

66 MA, MSPC, 24SP10475 Francis Crummey Jr. Note the close proximity between Crummey Senior and Junior’s application numbers, 24SP10376 and 24SP10475.

67 Tom McNally interview with Ernie O’Malley in Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmaid Ó Tuama (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2018), p108.

68 Séamus McGoran to Military Service Pensions Board, 2 June 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

69 Seán O’Neill to Board of Assessors, 30 July 1927, MA, MSPC, 24SP10376 Francis Joseph Crummey Sr.

70 Belfast News-Letter, 18 July 1935.

Leave a comment