Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

Rudimentary hand-grenades were first used in China almost 1500 years ago and came into widespread use among European armies in the mid-17th Century with the creation of specialised units of grenadiers. The weapon was widely viewed as obsolete by the early 20th Century but was given a new lease of life by the requirements of trench warfare during the Great War.

Millions of a new model of hand-grenade known as the No. 5 Mills bomb, named after its designer, were issued to British troops from 1915 onwards. It was intended to kill or wound through the fragmentation of its outer casing, which caused metal splinters to spread throughout the blast radius.

By the end of the war, the term “bomb” had become a generic term for this type of weapon and that is how it was commonly described during the Pogrom.

Sources of bombs

The IRA had access to government Mills bombs seized during the capture of Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks, such as that in Ballycastle in September 1920, when an unspecified number of bombs were taken. Supplies of similarly acquired bombs were also sent north by IRA General Headquarters.1

As early as October 1920, the RIC made their first discovery of IRA bombs in Belfast when they spotted Thomas Maguire, from Fernwood Street in Ballynafeigh, acting suspiciously on the Malone Road. After finding a loaded revolver on him, they searched his house and as well as rifles, revolvers, ammunition and IRA documents, found three Mills bombs.2

The IRA also had more unconventional sources: at various times, they operated at least three workshops in Belfast, making and filling home-made bombs. One was in the Market – a Cumann na mBan activist, Mary Russell, brought material there:

“… we got boys to take it out of Mackey’s [sic] Foundry and I gave it into the Engineering Department…Raw material for grenades … they said it was just the very thing they actually needed … We had a place in Ch[ich]ester Street where they made the hand-grenades and stuff … There was an accident happened in it. The chap that was in it was nearly blown to pieces.”3

A more elaborate facility was set up in the Pound around the time that the Pogrom began, with IRA Volunteers paid to work there around the clock; among the IRA documents seized when the RIC raided the 3rd Northern Division headquarters in St Mary’s Hall in March 1922 were a batch of time-sheets, “showing what appears to be the amount of work done by, as well as the total number of working hours per week of [twelve named men].”4

A home-made IRA grenade (© National Museum of Ireland HE:EWL.275)

Paul Cullen was one of those employees:

“In or about July 1920, he assisted at the fitting out of a munition factory at McMillan Place, Belfast, and was employed there full time, from, he believes, July 1920…He was paid for his work there. This factory was in charge of Sean McArdle, the Divisional Engineer, and applicant’s brother, Joseph, who was Brigade Engineer. Sixteen men were employed, eight on the day shift and eight on the night shift. The work was continuous, and the place was never raided.”5

Although the police never discovered the bomb factory, it was nearly found in September 1921 when a policeman on foot patrol wandered into the yard. Alarmed, the IRA quickly transferred the whole undertaking, including lathes and other equipment, to new premises in Arizona Street off the Glen Road in Andersonstown.

These two factories had a huge output, with 3rd Northern Division Quartermaster Tom McNally later recalling, “They made about 45,000 [casings for] grenades.” The IRA had national ambitions for the new factory: “There were some thousands of shells made but only about one thousand were fitted with the mechanism. It had been the intention, if there was no Treaty, to supply all Ireland with the grenades.”6

The factories were overseen by Seán McArdle, an architect and civil engineer by profession, who, as McNally said, “was scientifically interested in his invention – a contact grenade.” This was a modification to the standard Mills bomb mechanism that McArdle had come up with.7

To fill McArdle’s new model of grenade, the IRA also had to make its own explosives:

“We had a very enthusiastic Divisional Chemist with a very willing assistant. These men were most optimistic on the question of manufacturing gun-cotton which, needless to say, would have been of inestimable value to us. The Divisional Chemist came very near to his ambition and was always reporting progress – a slightly better explosion than the last time.”8

IRA members were dubious about the merits of McArdle’s invention: “The Volunteers did not take too kindly to the grenade, first of all because it was experimental; secondly because it was made by their own pals and by hand; thirdly because of a few accidents due to faulty and probably nervous handling.”9

There is no archival evidence of nationalists other than the IRA – for example, the Ancient Order of Hibernians – having access to bombs, so here, it is assumed they had none: a bomb thrown by nationalists was thrown by the IRA.

Meanwhile, loyalists also had a variety of sources for bombs. Members of the Ulster Special Constabulary (Specials) had access to government ones stored in the armouries of the police barracks to which they were assigned while, as will become apparent, loyalist paramilitaries also developed their own home-made bombs.

Spring 1921: the IRA begins using bombs

The first documented use of bombs in Belfast was by the IRA, who began using them against Crown forces in the spring of 1921.

The Ulster Club was a residential gentleman’s club in Castle Place, described by IRA officer Joe Murray as “Little Dublin Castle,” as he said it was home to the British Army’s General Officer Commanding Belfast military district as well as senior civil servants. On 4 April, two bombs were thrown at a sentry post at the rear of the building by Roger McCorley and Séamus McKenna – one failed to explode and the blast from the other was absorbed by the sandbag barrier. At a subsequent court martial, the sentry on duty identified Charlie Ryan as one of the bomb-throwers, although he had not actually been involved in the attack; Ryan was sentenced to 15 years’ penal servitude.10

Nine days later, a bomb was thrown at the rear of Springfield Road RIC Barracks, but caused no injuries or damage beyond breaking some of the windows.11

RIC Barracks, Springfield Road

The following month, the IRA mounted its first attack on a moving police target. On 17 May, an RIC lorry was returning to Springfield Road Barracks having escorted a payroll delivery to workers at the City Cemetery, when the IRA threw bombs at the vehicle. Newspaper reports said all three bombs exploded but without causing casualties, whereas an IRA officer who was among the attacking party later said, “there were two bombs thrown on the lorry…but they did not go off.”12

Summer 1921: loyalists begin using bombs

Loyalists began using bombs in the summer of 1921, but their attacks were of a very different character to those that had been mounted by the IRA.

During rioting in New Dock Street in Sailortown on 11 June, a Catholic woman, Sarah Millar, “had her eye destroyed by splinters from the bomb which blew away the right hand of William Kane;” the following day, Specials killed her brother Joseph in his own home.13

On 14 July, a loyalist mob threw a bomb into a shop owned by Mary Leonard in Garmoyle Street although on this occasion, no-one was hurt. Five men were subsequently charged, three of whom were found guilty; one of those acquitted, a man named Joseph McKee who later became an Imperial Guard, claimed to have been at home in bed at the time.14

Six people, two women and a girl as well as two men and a boy, were wounded on 21 August when a bomb was thrown into Tyrone Street in Carrick Hill from the direction of unionist Hanover Street.15

A week later, back in Sailortown, loyalists threw a bomb into the home of Peter Moan in Nelson Street. An ex-serviceman who had been on the Western Front, Moan was sure the bomb was home-made:

“‘When I went into the room after the explosion the place was filled with black smoke. The British Army do not use black powder in bombs, nor have they used it for some years. It was very black powder that was in the bomb and it must therefore have been manufactured locally.’”16

The Moan and Bohan families, after loyalists bombed their house in Nelson Street (Belfast Telegraph, 27 August 1921)

Moan and his family shared the house with his uncle and aunt, the Bohans – all escaped injury on this occasion, but loyalists were not yet finished with them. When three men carrying rifles came over her back wall on 2 January 1922, Josephine Moan identified McKee, acquitted for the Garmoyle Street bomb attack, as one of the men who forced herself, her children and her husband’s aunt from the house, then set fire to it. When charged in court, McKee also had an alibi for this incident.17

On 25 September, a bomb was thrown from nationalist Seaforde Street into a loyalist mob on the Newtownards Road. Implausibly, the nationalist press claimed that the bomb had first been thrown into Seaforde Street, then thrown back, but an IRA internal report stated the truth:

“On Sunday 24th [sic], large numbers of armed men were observed at the Newtownards Road end of Seaforde St and the position was so threatening that a Mills bomb had to be thrown by one of our men. The grenade was very effective and two of the Orange mob were killed and 34 wounded.”18

This was the largest number of casualties in a single bomb attack in Belfast during the Pogrom; it was also the first time the IRA had used a bomb against loyalists.

That evening, a bomb was thrown at a group of Catholic children playing in Milewater Street, off the York Road in the north of the city; five people were wounded but George Berry, an ex-soldier who had been expelled from his job at the outset of the Pogrom in 1920, was killed. At the inquest into his death, one of the members of the coroner’s jury alleged that police stationed at the end of the street had left their post shortly before the bombing. There were two side-streets off Milewater Street; the second one was called Weaver Street.19

November 1921: the IRA targets trams

At the end of November, the IRA changed its use of bombs. No longer were they being used to attack the military and police or being used defensively against loyalist mobs. Now they were being used to attack people on trams, with the targets chosen on a sectarian basis.

On 22 November, tram No. 26 was travelling along Corporation Street, packed with shipyard workers returning home from the Workman & Clark yard to the Oldpark Road. As it passed Little Patrick Street, a group of IRA men threw a bomb through the window:

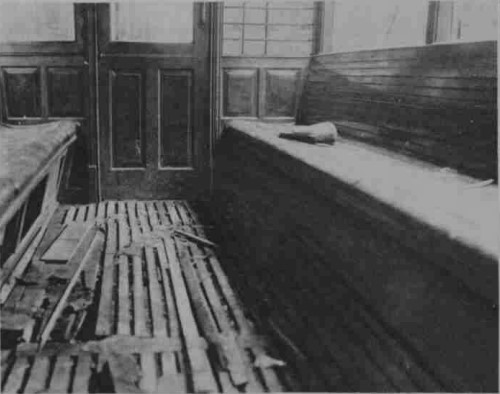

“The explosion killed two men outright, seriously wounded four, and caused severe injuries to many other passengers. The glass sides of the tram were blown out, while the floor was shattered by the terrific force of the explosion. The scene that followed is indescribable, the cries and moanings of the wounded being harrowing in the extreme. The bodies of those who had been killed and wounded were instantly removed from the wreckage, and those who were untouched assisted their fortunate comrades to the footpath to adjacent shops.”20

The fact that the tram was densely packed meant that more of the impact of the blast was absorbed by those closest to the explosion, thus preventing a higher number of casualties: two were killed and several wounded. The casualty toll was higher when the IRA staged a similar attack two days later, again targeting shipyard workers, this time on a tram in Royal Avenue bound for the Shankill Road: four men were killed and five wounded. Seán Montgomery accompanied Alf Mullan, who threw the bomb:

“Things were getting very bad so orders were given to bomb two shipyard trams, one was done in Corporation Street in the early part of the week. In Lancaster Street I was approached by Alf Mullan. He could not get anyone to cover him as he had orders to do two trams. I asked him if it was an order and he said it was so I went with him … An armoured car came along so we moved to Winetavern Street. While waiting a policeman who knew Alf told him to get to hell from there as he was on duty, so we went off to Berry Street and in front of the Grand Central Hotel he did the job. I covered him … Well there was a bit of a stink about it.”21

Aftermath of an IRA bomb attack on a tram (Illustrated London News, 3 December 1921)

One of those wounded was James Bell of Snugville Street in the Shankill:

“When asked were there many passengers in the tram Bell went on, ‘Packed, you know what a workmen’s car is like coming from the Island. We were sitting where we could and standing all round. Nobody expected anything in Royal Avenue above all places … The glass shattered and the pieces of the bomb flew round us. Then there was the awful steamy, smoky smell of the explosive. Darkness. And I remember nothing more until now.’”22

The IRA attempted to target another tram at the junction of Berry Street and Royal Avenue on 30 November, but the bomb failed to explode. On 23 December, they threw a bomb onto a tram on the Grosvenor Road but it was kicked off the platform by an alert passenger.23

At the start of January 1922, trams also began featuring in loyalist bomb attacks – not as targets, but as platforms from which bombs could be thrown into nationalist streets.

The first such incident was on 1 January, when a bomb was thrown from a tram into Little Patrick Street, the street from which the IRA threw the bomb in its first tram attack; although the loyalist bomb caused no casualties, the retaliatory message it sent was clear. A similar attack followed two days later, in Foundry Street in Ballymacarrett, but again, no-one was hurt. A third bomb was thrown from a tram into Curtis Street off York Street on 27 February, wounding three; the police suspected that it was thrown by Alex “Buck Alec” Robinson.24

Spring 1922: loyalist escalation

Loyalists’ use of bombs was intermittent during the autumn of 1921. The one fatal exception was on 29 November, when a bomb was thrown into Keegan Street in the majority-nationalist Market area, killing Annie McNamara and wounding two of her neighbours. However, the first three months of 1922 saw a dramatic escalation in the frequency of loyalist bomb attacks.25

The police report for 4 January noted that, “At 8:30pm, a dud bomb was thrown from North Derby St into Weaver St apparently at Charles Boyd, RC [Roman Catholic], labourer, 29 Weaver St. No harm was done as a result.” Although this attempt failed to kill or wound anyone, loyalists still had plans for Weaver Street.26

Annie McNamara, killed by a loyalist bomb on 29 November 1921 (image courtesy of Aisling Heath & Pat McGuinness)

Five more loyalist attacks followed during January, including another one on children at play on 10 January: the RIC log of daily incidents said that “a bomb was thrown in Herbert Street, about 20 yards from Crumlin Road, near Ardoyne, RC area, six children were wounded. The bomb was thrown from Hooker Street, vacant ground, unionist area, over the houses into Herbert Street.”27

Loyalists threw a bomb at children playing in Herbert Street; a boy is standing beside the small crater where the bomb landed

Then on 13 February, a bomb attack took place which claimed the lives of six Catholics, the highest number of fatalities in a single bomb-throwing incident.

Weaver Street was one of a tiny cluster of just three streets off the York Road in which the majority of residents were Catholic. Also comprising Milewater Street and Shore Street, the neighbourhood was too small to even be described as a “Catholic enclave” in a predominantly-Protestant area; the 1911 Census showed just 108 households between the three streets, 64% of which were Catholic. Almost 30% of the entire population of those streets, including children as young as 13, worked in flax or linen mills.28

Nadia Dobrianska has written an extensive examination of the events of 13 February and their aftermath:

“On the evening of 13 February, Weaver Street was peaceful. Approximately thirty children were out in the street. They were playing skipping-rope, swinging on ropes tied to lamp posts, singing on the doorsteps of their homes and playing marbles and other games, while their parents were also out watching them. Between 8pm and 9pm, the games were interrupted by two Special constables … who chased the children from the Milewater Street corner where they were skipping. The Specials sent them to the middle of Weaver Street, as witnessed by Catherine MacNeill, mother of Rose Anne MacNeill.”29

A few minutes later,

“… three policemen were seen coming from Shore Road to North Derby Street [at the other end of Weaver Street] and speaking with two civilians on North Derby Street. The policemen left and the two civilians were seen walking up and down towards Jennymount Mill on North Derby Street and passing Weaver Street corner. One of the civilians threw the bomb into Weaver Street and a revolver was fired into the street after that.”30

Sweeping the street with revolver firing stopped parents from reaching their wounded children. Two girls died that night, Ellen Johnston and Catherine Kennedy; two more died the following morning, Rose Anne MacNeill and Eliza O’Hanlon; two adult women later died from their wounds, Margaret Smyth and Mary Owen. Sixteen other children and adults were wounded; the youngest casualty was a 6-year-old girl.31

Various historians – including this author – have portrayed the attack on Weaver Street as an act of revenge for the IRA’s kidnapping of Tyrone and Fermanagh unionists on the night of 7/8 February and its attack on a detachment of Specials stopped at Clones train station on 11 February, in which four Specials were killed and eight wounded. However, it is now clear that while events in Clones may have been a trigger, there had already been a series of loyalist bomb attacks on Weaver Street and its vicinity since the previous summer – the one on 13 February was simply the first which succeeded in killing multiple Catholics.32

Catherine Kennedy, one of the children killed by the bomb in Weaver Street (Irish News, 23 February 2022)

The attack was deplored by James Craig, unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, although he pointed to the border kidnappings and Clones as provocations. It was furiously denounced by the Catholic hierarchy, by the nationalist press both north and south and by Michael Collins, chairman of the Provisional Government in Dublin. It was debated in Westminster, with the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill sending a telegram to Collins describing it as “the worst thing that has happened in Ireland for the last three years” and one to Craig in which he said, “This deed has no equal for savagery in recent Irish history.”33

However, the condemnation of the Weaver Street attack was not universal. Some within loyalism saw it as something to be emulated and eight more bomb attacks on Catholics followed later in February, killing one and wounding ten.

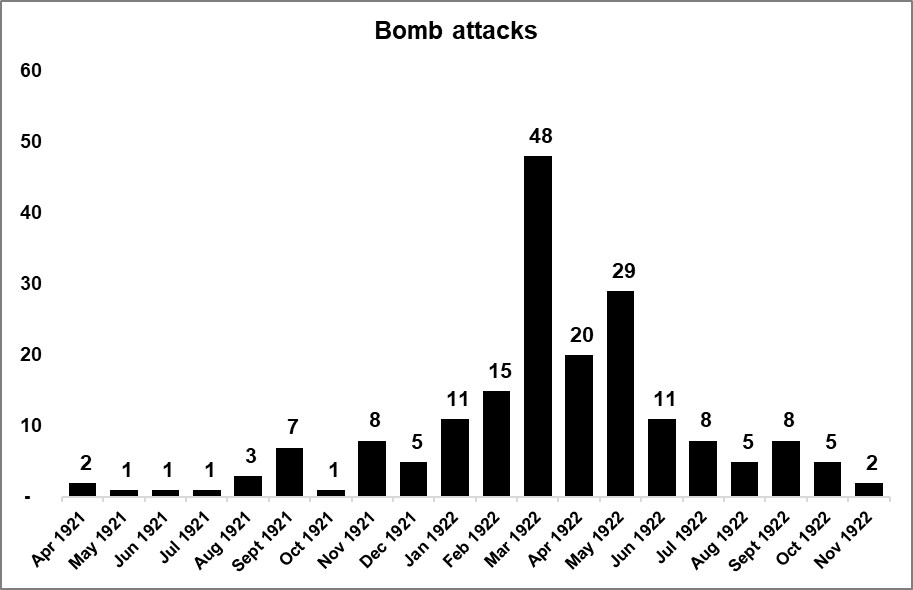

But even that level of bomb-related violence gave no indication of what March had in store. During that month alone, loyalists carried out 29 bomb attacks, with several days seeing as many as four separate incidents in different parts of the city.

The ferocity of loyalist bomb-throwers was not only directed at Catholics: on 7 March, bombs were thrown at two separate patrols of British troops – one, in Hanover Street off the Old Lodge Road, wounded four soldiers of the Norfolk Regiment, while another in Dale Street near North Queen Street, thrown “from unionist locality of York Street,” failed to injure anyone.34

Some attacks were aimed at nationalist streets but the bombs did not discriminate in who they wounded: among 14 people hit by splinters from a bomb thrown into Foundry Street on 13 March were five Protestants, including one woman from Bangor, which indicates that passengers going to or from the nearby Belfast & County Down Railway station were caught up in the attack.35

Catholic homes were bombed while their occupants slept: just after 5am on 18 March, a bomb was thrown into the bedroom of an elderly woman, Rose McGreevy, and her niece, Annie Mullan, in Thompson Street in Ballymacarrett, killing both.36

A loyalist bomb killed Rose McGreevy and Annie Mullan while they slept (Illustrated London News, 25 March 1922)

On 27 March, a fire broke out in a jam factory in Unity Street in Carrick Hill just after 2:30am; several residents had come out to watch the Fire Brigade tackle the blaze when a bomb was thrown into the crowd of onlookers, killing one and injuring three. The police noted, “All the wounded are RCs.”37

Loyalist bomb-throwers even killed Protestant children, if inadvertently. On 31 March, Francis and Joseph Donnelly were killed in an attack on their home in Brown Street off Millfield; their surname may have led their killers to believe they were Catholics, but the family were members of the Church of Ireland. The police believed that John Williamson and George Scott were the individuals responsible – both were members of the Specials.38

The IRA was not idle during early 1922, but in terms of bomb-throwing, it failed to match the intensity of loyalists. It threw bombs on eighteen occasions in the first three months of the year, including twice at RIC Lancia armoured cars but those attempts caused no casualties among the police. The IRA returned to the tactic of attacking trams when, on 14 March, they threw a bomb onto a tram in Mountpottinger Road in Ballymacarret but it failed to explode. Four days later, they threw one at a tram coming down the Antrim Road as it passed Churchill Street in the New Lodge: this time, one man, Alexander Devaney, was killed and three wounded.39

Crucially, the IRA’s very sporadic use of bombs in early 1922 utterly failed to deter loyalists’ increasing use of this weapon.

April 1922: a month of misery for Sergeant Curtis

On 4 April, the police daily report noted that in Ballymacarrett,

“At 9:30pm, a bomb was thrown in Chemical St, RC area. It exploded without doing any injury. It was alleged to have been fired out of Davison’s Yard, where No. 23 Platoon Special Constabulary are stationed. The officer commanding was present at the time and reports that the bomb was not thrown from there as all bombs are under his control.”40

Half an hour later, a second incident in the same area was omitted from the police report but included in the daily summary for that day issued by the Provisional Government in Dublin: “10pm Another bomb was thrown from Davidson’s Yard into Chemical Street. It fell at the feet of Sergt Curtis, Mountpottinger Barracks. The detonator only exploded.” This was to be the start of a horrific few weeks for Sergeant Curtis.41

He was a Catholic, so even though he was a policeman, his religion made him a target for loyalists; the police report for 13 April stated:

“At 10:05pm, a bomb was thrown into the back yard of number 33 Bendigo Street [off the Ravenhill Road], unionist area. It exploded and broke the kitchen, scullery and bedroom windows. The house is occupied by Sergt Curtis, RIC Mountpottinger, an RC. His wife and child were in the house at the time but were not injured.”42

A week later, Ballymacarrett erupted into savage violence, with Specials and other loyalists sniping into Catholic streets and a wave of evictions and house-burnings. The unfortunate Sergeant Curtis was targeted in the IRA’s response: “At 6:45pm, a bomb was thrown at a Lancia car at the junction of Thompson Street and Woodstock Street, RC area. Sergt Curtis, who was in charge, is suffering from shell shock. The bomb exploded under the car but did not injure it.”43

It would have been no consolation to Sergeant Curtis that Belfast saw less than half the number of bomb attacks in April that there had been in March: 20 compared to 48. After having had bombs thrown at him three times in three weeks, including by his own side, it was little wonder that he was shellshocked.

Near the end of April, the RIC daily log contained a first reference to another type of weapon:

“At 10pm, a bottle containing paraffin oil with a bundle of soft cords through the neck set on fire was thrown from an entry at the back of Ravenhill Road through the kitchen window of Thomas Gunn, RC, 105 Ravenhill Road. It started a fire but it was put out with a bucket of water.”44

This was clearly an early forerunner to a weapon that became ubiquitous in the later Troubles, the petrol bomb, but Tim Wilson has noted, “Although much celebrated in anarchist song and story, in practice petrol remained effectively ‘unweaponized’ until well into the twentieth century. The creation of the society of mass vehicle ownership was a prior condition for its dissemination as a weapon.” However, it is noteworthy that this was the first time that a thrown device like this was explicitly mentioned by the police in Belfast – until then, burnings of buildings had been conducted by sprinkling paraffin, then lighting it with matches or burning scraps of wastepaper.45

Another new weapon would emerge the following month.

May 1922: the appearance of “infernal machines”

May 1922 was the only month of the entire period in which the IRA mounted more bomb attacks than loyalists; in fact, the number was almost double, nineteen compared to ten. This was obviously related to the start of the Belfast element of the IRA’s “northern offensive” from 18 May.

However, before the offensive began, the IRA had already deployed a new type of bomb, immediately branded an “infernal machine” by the unionist press.46

At almost 11pm on 11 May, when the tram on the Malone Road-Shankill Road route had made its final journey of the day, it returned to its depot in Ardoyne. There, the conductor, John Mansfield, noticed that an attaché case had been left on the vehicle by a passenger. He brought it into the cashier’s office and had just put it down to fill out a lost property form when it exploded. One of his colleagues, James Kennedy, said,

“… there was a loud report and we were all knocked helter-skelter and I felt a number of sharp stabs in my legs and I also thought I had been blinded. My clothes went on fire and I rolled about the floor in an endeavour to beat out the flames. Then I saw that some of the other fellows had been wounded and Mansfield seemed to be worst of all.”47

Four tram workers were wounded, with Mansfield succumbing to his wounds the following day. When the military arrived, they recovered pieces of the bomb, bullets and nails with which it had been packed and portions of brass wheels like those found in an alarm clock.48

Three days later, a Mills bomb adapted to take a time fuse was discovered on a tram in Castle Junction. The conductor heard a “sizzling noise” coming from the top deck and on investigating, found a bomb with the fuse burning; luckily, an ex-serviceman grabbed a bucket of water from a nearby flower-seller and poured it over the bomb, extinguishing the fuse.49

A week later, at 9am on Monday 22 May, when Corporation telephone engineers re-opened a manhole in Arthur Square in the city centre at which they had been working until the previous Friday, they discovered a wooden box had been left in the manhole, covered with sacking. They notified the police, who sought assistance from the British Army’s Royal Engineers in Victoria Barracks. When the military arrived, an officer ordered the manhole to be flooded – this was done by the Fire Brigade.50

Fireman flooding a manhole in Arthur Square where an “infernal machine” was discovered (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 27 May 1922)

By early afternoon, it was judged safe to remove the box and when they opened it, the soldiers found what police described as a “clock mine,” fitted with a timer and due to go off at 2pm; however, the timer mechanism had misfunctioned and stopped at 8:30 that morning.51

The Royal Engineers took the device back to Victoria Barracks for examination and informed the RIC that “it was an exact replica of the one that exploded at the tramway depot, Ardoyne…he also stated that it was highly incendiary but not highly explosive.” The military found the bomb to be made up of 20lbs of one type of explosive, now damp from the Fire Brigade’s efforts, 1lb of another type and 5lbs of ammunition of various calibres, obviously intended to become shrapnel; a senior officer judged the explosives to have been home-made and recommended further analysis.52

The Belfast City Chemist, John H. Totton, was asked to conduct this analysis – he made a startling discovery:

“The casing of the bomb consisted of a cylindrical tin canister, 3 inches in diameter and 6½ inches long. Down the middle ran a stiff paper cylinder, 7/8 inches in diameter, held in position by light cardboard discs. The paper cylinder had printed on it the words ‘Public Record Office of Ireland. Certified Copy.’”53

In 1922, the Public Record Office of Ireland was located in the Four Courts in Dublin, which had been occupied by the anti-Treaty IRA since mid-April.

Dr Totton’s report went on to outline how the bomb was thus divided into “an outer section of considerable capacity, and an inner of much smaller capacity…Whatever mechanism had originally been attached to explode or fire the bomb had been detached, only a small spiral spring remaining in the inner section.” In his opinion, “Regarded as an explosive the bomb was of little value, but for incendiary purposes it was of effective composition.”54

Hugh Corvin, who was then Quartermaster of the anti-Treaty 3rd Northern Division, later confirmed the provenance of the clock mines: “The policy of the new GHQ at that time was to carry on with the burning campaign and we were supplied with incendiary bombs from Dublin for that purpose.”55

In 1950, an anti-Treaty IRA officer named Mossy Donegan recalled that “We had plenty rifles and to spare…mines were also available. As a matter of fact, later on a lorry of mines parked in the Four Courts and ready to go north was blown up during the attack on the Courts.”56

Until now, it has always been assumed that when Donegan said “mines,” he meant landmines. If, however, he meant incendiary clock mines like the ones used in Ardoyne tram depot and Arthur Square, then that raises an interesting possibility. If a truckload of such mines were made in the Four Courts, then a truckload must also have been stored there – did they contribute to the fire and explosion which destroyed the Four Courts on 30 June?

Did incendiary bombs intended for use in Belfast contribute to the fire and explosion at the Four Courts in Dublin?

The northern government did not release Dr Totton’s findings – by the time he completed his report, the Provisional Government had captured the Four Courts and there was no longer any political capital to be made from making the chemist’s discovery publicly known.

Incendiary bombs with timer fuses were used in attacks on the Model School in Divis Street and a cinema on York Street on 26 May and in the same cinema again on 29 June; these incidents were among dozens of arson attacks mounted as part of the IRA’s offensive.57

John O’Neill has highlighted the IRA’s development of incendiary grenades and he even created an impression made from a mould discovered in Wexford, although there is no archival evidence of this particular weapon being used in Belfast. Police and newspaper reports simply referred to “fires being discovered” or “incendiary bombs” being thrown – which could indicate either bottles filled with paraffin or Wexford-type bombs – while others mentioned the older method of paraffin being sprinkled and set alight. Police seizures of IRA arms dumps in the summer and autumn of 1922 referred to the capture of “incendiary bombs” without detailing the exact kind of weapon. As it is impossible to be certain about which specific types of bombs – if any – were used in most arson attacks, they are not included in this analysis.58

However, there was no doubt as to the nature of other IRA bomb attacks in Belfast during the offensive.

On 23 May, three attacks took place on the Falls Road within 200 metres and a quarter of an hour of each other: “At 3:15pm, a bomb was thrown at the windows of the house of Annie Hill, 74 years, (P [Protestant]) 2 Thames Street.” At exactly the same time, “a bomb was thrown at the parlour window of Agnes Johnston, 40 years, (P) 2 Nansen Street.” Then, “At 3:30pm, a bomb was thrown into the back yard of the house of Mrs Annie McMullan, 50 years, (P) 1 Fallswater Street.” Although the bombs caused no injuries, the distances and timing reveal careful co-ordination and possibly even the same attackers – this was a planned sectarian attack on three separate Protestant women living in an overwhelmingly nationalist area.59

At teatime the following day, the area around Carrick Hill erupted with the sound of multiple explosions. Shortly before 6pm, “a general attack was made on trams returning with workers through North Street” – the IRA threw three bombs, one in North Street, one on the Old Lodge Road and one at a police Lancia on Peter’s Hill; the bombs were accompanied by rifle and revolver fire, leaving one woman dead and ten people injured. All eleven casualties were Protestants. A few minutes later, the IRA threw two bombs at trams in Clifton Street, but these caused no injuries.60

The IRA did use bombs to attack police in Belfast during the offensive – on 24 May, one was thrown in Chemical Street in Ballymacarrett, wounding one member of a Specials patrol who had emerged from the post in Davidson’s Yard to investigate a shooting incident. Two days later, three bombs were thrown into the same post in quick succession but this time, there were no casualties.61

Summer and autumn 1922: the end of the Pogrom

The number of bomb attacks in Belfast dropped significantly from June onwards.

By then, the IRA offensive was a spent force, although arson attacks continued for much of June; many officers and men began fleeing south of the border to avoid being interned.

Meanwhile, Loyalist tactics had changed – now, instead of bombs being thrown into Catholic homes and shops, Catholics were being physically evicted from their homes by mobs; the evictions were frequently accompanied by house-burnings, a return to an earlier practice. Isolated Catholics living in predominantly Protestant areas, such as in east Belfast south of the Albertbridge Road, were particularly affected. Thousands of Catholics became refugees in the south and in Scotland.

The violent storm which engulfed the tiny community around Weaver Street was typical of this period. During the afternoon of Thursday 18 May, Thomas McCaffrey from Shore Street was shot dead on a tram while travelling into the city along the York Road. On Saturday 20 May, according to a Provisional Government report, the district was “attacked by large body of armed men who opened fire on it from a piece of waste ground;” Thomas McShane, a Catholic living in nearby Jennymount Street, was “followed into his home by a crowd who, bursting open the door, caught deceased in the hall and shot him.”62

On Sunday 21 May, the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee said that “Weaver Street, Milewater Street and Shore Street were attacked by the Orangemen. The Catholics were driven from Shore Street and their houses occupied by Orange gunmen who used them as sniping posts. Some Catholics had to be removed in the armoured car to safety in other districts.” The unionist Northern Whig painted this as being somehow voluntary, calling it “an exodus of the inhabitants … some of the people thinking discretion the better part of valour left.”63

Evicted Weaver Street residents load their belongings onto a cart (image courtesy https://treasonfelony.wordpress.com/)

There were only eleven bomb attacks in total in June, and by 7 July, the British Army could make what was happening sound almost recreational compared to the savagery of the preceding months: “A little bomb throwing in Belfast, otherwise quiet in Ulster.” Only eight bombs were thrown in July and by August the number had dropped to five, although one of these was thrown by loyalists into a shop in North Queen Street, wounding eight Catholics.64

The first week of September saw two bombs thrown by the IRA at police Lancias in the Marrowbone, but the most serious attack was one by a loyalist on 15 September. A resident of the Lower Falls told the Belfast Telegraph that she had seen a man walking along the Grosvenor Road – when he got to the junction of Cullingtree Road, he started looking around, as if searching for someone:

“‘Then he did the coolest thing imaginable,’ she continued. ‘He brought his pipe from his pocket, after carefully filling it, he set it alight. While doing this, he turned his back towards Slate Street and seemed to be enjoying his smoke as he waited. Suddenly, when he thought everyone had been put off their guard, he wheeled and deliberately flung the bomb into the centre of the group of people at the opposite corner, and then he turned and fled to the Grosvenor Road again.’”65

Lizzie Cannon, a 30-year-old woman, was killed and eight other Catholics wounded; she was the last person to be killed by a bomb during the Pogrom.

The following week, Edward Gill, a Special Constable from nearby Devonshire Street, mere yards from where the bomb had been thrown, was charged. In court, he claimed that he had never even seen a bomb until he went to Balmoral for bomb-throwing practice with the Specials. With no apparent sense of irony, the same edition of the Belfast News-Letter that reported his claim also carried a photographic feature titled “With the Specials at Balmoral,” with one of the photos captioned “Instruction in bomb-throwing.” Gill was acquitted.66

“With the Specials at Balmoral – Instruction in bomb-throwing” (Belfast News-Letter, 21 September 1922)

Although there were a final few bombs thrown in October and November, one thrown on 22 September is the most suitable to bring this overview to a close. The police log reported that, “About 8:45pm, a bomb was thrown through the parlour window of 3 Bryson Street, Protestant area, occupied by Robert Forsythe, a mixed family. The females are all RCs and the males Protestants. The furniture was wrecked and some damage done to the walls, but no person injured.”67

As the family targeted were of mixed religions, it is impossible to surmise who threw this particular bomb. But at least no-one was killed or wounded.

Summary & conclusions

From April 1921 to November 1922, there were 191 bomb attacks in Belfast; as incendiary attacks that were part of the IRA’s arson campaign are not included, that means 191 bomb attacks against people. There were two clear peaks, in March 1922, when loyalist use of the weapon was at its most intense, and in May of that year, coinciding with the IRA’s “northern offensive.”

Sources: PRONI, HA/5/149-151D Reports by RIC & RUC on incidents in Belfast, November 1921-December 1922; newspaper reports: Belfast News-Letter, Northern Whig, Belfast Telegraph, Irish News, Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner.

Of the 191 attacks, responsibility cannot be attributed in 16 incidents, mainly because in those cases, the bombs fell in the street in interfaces or in mixed streets. For the remaining 175 attacks, responsibility can be assigned with reasonable certainty – and generally was by the police, at least in terms of the religion of the target and often also that of the area from which a bomb was thrown.

Including Specials on or off duty, loyalists were responsible for many more attacks, 111 or 58% of the total; the IRA was responsible for the remaining 64 or 34% of the total.

One of the most striking facts is that in 70% of the attacks, 134 in all, there were no casualties. This ineffectiveness was due to defects in manufacturing and/or mistakes in use, the latter a consequence of poor training. Very often, police reports would note that only the detonator had gone off, but not the explosive charge; sometimes, neither would work. That explains why so many people had bombs thrown through their front windows yet managed to walk out of their houses unscathed; of course, they were still subjected to shock and terror, so even a malfunctioning bomb had some value to the thrower.

But not all bombs were duds. The ones that worked as intended killed 29 people and wounded 201. Loyalists were responsible for 16 killings and 123 non-fatal injuries, the IRA for 13 killings and 75 non-fatal injuries. Three people were wounded at the hands of unknown attackers.

Another striking fact is that fully 60% of all the casualties that the IRA inflicted were in just three attacks: the bomb thrown from (but not into) Seaforde Street in September 1921 and the first two tram attacks in November of that year. The corollary is also notable: there were no casualties at all in over 75% of its attacks, compared to a non-casualty rate of 63% for loyalist attacks. This could be explained by a couple of potential factors: a greater reliance by the IRA on ineffective home-made bombs, or a higher proportion of ex-servicemen with better, British Army training among loyalist ranks.

There was also a difference between the IRA’s and loyalists’ tactical use of bombs, although the gap was not as wide as might be imagined.

Only twelve IRA attacks, just under 20%, were aimed at the Crown forces, ranging from its very first one on the military sentry at the Ulster Club to bombs thrown at police Lancias or Specials’ posts; one of those attacks wounded a Special, the rest were unsuccessful. The remaining 80% of its attacks were aimed at Protestant civilians.

For loyalists, it is easier to list the attacks they made that did not target Catholic civilians: two against the British Army and the one that killed the Protestant Donnelly children – and in the latter, they thought they were attacking Catholics. Leaving aside the Donnelly case, 98% of loyalist attacks were on ordinary Catholics.

Neither side pulled back from potential mass-casualty attacks: the IRA targeted trams packed full of workers returning home, while loyalists targeted groups of children playing in the street. The bombs thrown onto the trams in Corporation Street and Royal Avenue and the one thrown into Weaver Street were the most notorious because of the numbers of people killed, but they were not unique in terms of intent – each side tried to replicate their successes in those incidents. However, shipyard workers were not the biggest barrier to the establishment of an Irish republic and Ulster was not under attack by pre-teen girls armed with skipping ropes; in each of these cases, the aim was to kill and wound as many as possible of the other religion.

Where the two sides did differ was in terms of persistent and repeated targeting – this was a unique feature of loyalist attacks. They threw bombs at St Matthew’s church on the Newtownards Road five times in five weeks during March-April 1922. When the bomb thrown into the Moan home on Nelson Street failed to intimidate the family, loyalists returned after a few months and burned them out. They made repeated attempts to bomb the vicinity of Weaver Street and even when they succeeded in doing so, they still evicted the remaining families three months later.

1920 had opened with Labour gaining twelve seats on Belfast Corporation in the local election; their vote share of 17.7% demonstrated that there was public appetite for politics that stood apart from the traditional sectarian binaries – but Labour councillors were among those driven from their jobs in the initial workplace expulsions in July of that year. Just over two years later, the mixed-religion Forsythe family in Bryson Street were attempting to live in quiet disregard for the same sectarian binaries and for that, someone threw a bomb into their front room. Illustrating the depth to which Belfast had plunged since the January 1920 election, that bomb could equally as plausibly have been thrown by republicans or loyalists.

References:

1 Military Archives (MA), Bureau of Military History (BMH), WS0762 Liam McMullen; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 4 September 1920.

2 Northern Whig, 13 December 1920; MA, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), 24SP9865 Thomas Maguire.

3 MA, MSPC, MSP34REF24769 Mary Russell. The original typescript of the interview states that the factory was in “Chester Street” but as there was no street of that name in Belfast, it is clear that the MSP clerk misheard what Russell said.

4 Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA-32/1/130.

5 Paul Cullen sworn statement to Advisory Committee, 25 October 1939, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF55547 Paul Cullen.

6 Tom McNally interview with Ernie O’Malley in Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmaid Ó Tuama (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2018), p107; MA, BMH, WS0410 Thomas McNally.

7 Thomas McNally to Military Service Registration Board, 21 March 1938, MA, MSPC, DP9324 John McArdle (2RB4036).

8 MA, BMH, WS0410 Thomas McNally.

9 Ibid.

10 MA, BMH, WS0412 Joseph Murray; Belfast News-Letter, 5 April & 13 May 1921.

11 Belfast News-Letter, 14 April 1921.

12 Belfast News-Letter, 18 May 1921; Joseph Savage Junior sworn statement to Advisory Committee, 9 November 1937, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF32271 Joseph Savage Junior.

13 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 18 June 1921.

14 Belfast News-Letter, 30 July 1921.

15 Belfast News-Letter, 22 August 1921.

16 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 3 September 1921.

17 Information form of Josephine Moan, 7 January 1922, PRONI, Barnsley Sloan, Joseph Clarke and Joseph McKee – intimidation of Josephine Moan, BELF/1/1/2/68/9.

18 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 1 October 1921; 2nd Battalion Operations Report to O/C No. 1 (Belfast) Brigade, September 1921, Richard Mulcahy Papers, UCD Archives, P7/A/24.

19 Belfast Telegraph, 26 September 1921; Northern Whig, 19 October 1921.

20 Northern Whig, 23 November 1921.

21 Seán Montgomery statement, Seán O’Mahony Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 44,061/6.

22 Northern Whig, 25 November 1921.

23 Northern Whig, 1 & 24 December 1921.

24 Occurrences in Belfast on 1 & 3 January and 27 February 1922, 2 & 4 January and 28 February 1922, PRONI, HA/5/149 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, Nov. 1921-Feb. 1922 [as the occurrences reports were always completed the following day, hereafter, only the day on which the incidents took place will be given]; PRONI, HA/5/2192 Robinson, Alexander, Andrew St, Belfast.

25 Irish News, 30 November 1921.

26 Occurrences in Belfast on 4 January 1922, PRONI, HA/5/149 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, Nov. 1921-Feb. 1922.

27 Occurrences in Belfast on 10 January 1922, PRONI, HA/5/149 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, Nov. 1921-Feb. 1922.

28 1911 Census, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), https://nationalarchives.ie/collections/search-the-census/search-results/#census_year=1911&ded__icontains=Duncairn+Ward

29 Nadia Dobrianska, ‘The Weaver Street bombing in Belfast 1922: violence, politics and memory’ in Irish Historical Studies (2023), volume 47 issue 172, pp259–277.

30 Ibid. Newspaper reports of the inquest hearings said the policemen were seen coming from Shore Road to North Derby Street – this would have been physically impossible as the Shore Road begins 6km from North Derby Street. The witness, Agnes O’Neill, most likely said she saw them coming from York Road, where there was an RIC barracks, but the court reporter misheard this as Shore Road; see Belfast News-Letter & Northern Whig, both 4 March 1922.

31 Ibid.

32 Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (Cork, Mercier Press, 2013), p102; Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001), p167; Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition 1920‒1922 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2006), p116.

33 Dobrianska, ‘The Weaver Street bombing.’

34 Occurrences in Belfast on 7 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922.

35 Occurrences in Belfast on 13 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922.

36 Occurrences in Belfast on 18 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922.

37 Occurrences in Belfast on 27 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922.

38 Head Constable J. Wilkin to Detective Branch, RUC, 7 October 1922, PRONI, Williamson, John, Fortingale St, Belfast, HA/5/2210.

39 Occurrences in Belfast on 8 January 1922, PRONI, HA/5/149 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, Nov. 1921-Feb. 1922 [bomb thrown at RIC Lancia in Coates Street]; Occurrences in Belfast on 8 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922 [bomb thrown at RIC Lancia in Stanhope Street]; Occurrences in Belfast on 14 & 18 March 1922, PRONI, HA/5/150 Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, March 1922 [bomb attacks on trams].

40 Occurrences in Belfast on 4 April 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

41 Belfast summary, 4 April 1922, NAI, NEBB 1/1/1 Belfast atrocities.

42 Occurrences in Belfast on 13 April 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

43 Occurrences in Belfast on 20 April 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

44 Occurrences in Belfast on 25 April 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

45 T.K. Wilson, Killing Strangers: How Political Violence Became Modern (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2020), p153.

46 Belfast News-Letter, 12 May 1922. The evening paper, the Belfast Telegraph, copied the phrase in its edition later that day.

47 Belfast Telegraph, 12 May 1922.

48 Ibid.

49 Northern Whig, 16 May 1922.

50 Northern Whig, 23 May 1922.

51 Occurrences in Belfast on 22 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922; Northern Whig, 23 May 1922.

52 DI John Armstrong to City Commissioner, RUC, 31 July 1922 & Lieutenant-Colonel [name not stated], Royal Engineers to Divisional Commissioner, RIC, 24 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/226 Bomb in manhole, Arthur Square, Belfast.

53 Dr John H. Totton to City Commissioner, RUC, 28 July 1922, PRONI, HA/5/226 Bomb in manhole, Arthur Square, Belfast.

54 Ibid.

55 Hugh Corvin sworn statement to Advisory Committee, 17 July 1936, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF24082 Hugh Corvin.

56 Mossy Donegan to Florence O’Donoghue, 15 September 1950, Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI, Ms 31,423 (6).

57 Northern Whig, 27 May 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 30 June 1922; Occurrences in Belfast on various dates, PRONI, HA/5/151B Reports by RIC & RUC on incidents in Belfast, June-July 1922.

58 John O’Neill, ‘IRA incendiary bombs,’ https://treasonfelony.wordpress.com/2020/06/12/ira-incendiary-bombs/; for examples of police seizures of “incendiary bombs,” see: Belfast News-Letter, 5 July 1922 [Alexander Street West – Lower Falls]; Northern Whig, 15 July 1922 [Sanderson Street – Marrowbone]; Belfast News-Letter, 15 July 1922 [Albert Street – Lower Falls].

59 Occurrences in Belfast on 23 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

60 Occurrences in Belfast on 24 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

61 Occurrences in Belfast on 24 & 26 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

62 Report for 20 May, NAI, TSCH/3/S5462 Northern Ireland outrages Jan-Oct 1922; Northern Whig, 7 June 1922 [inquest report for both killings].

63 Report for 21 May 1922, NLI, Ms 8,457-12 Art Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee; Northern Whig, 22 May 1922.

64 GHQ Belfast Operations Report, 7 July 1922, The National Archives, Colonial Office: Irish Free State correspondence, CO 739/11 War Office – my thanks to Nadia Dobrianska for providing this reference; Occurrences in Belfast on 29 August 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151C Reports by RUC on incidents in Belfast, August-September 1922.

65 Occurrences in Belfast on 4 & 5 September 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151C Reports by RUC on incidents in Belfast, August-September 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 16 September 1922.

66 Belfast News-Letter, 21 September & 4 October 1922.

67 Occurrences in Belfast on 22 September 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151C Reports by RUC on incidents in Belfast, August-September 1922.

Leave a comment