Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

1914: the Western Front

Patrick Barnes was born on 8 August 1888. In 1901, he lived with his widowed mother and three siblings off Divis Street in Lettuce Hill, which was later renamed John Street. On 20 February 1908, aged 19, he became known as 8937 Rifleman Barnes, Patrick, when he enlisted in the 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles (RIR).1

He later said that he “served six years in India come from Aden in 1914 went out to France to fight for my king and country.” When the Great War began, the 1st RIR were stationed in Aden in the Middle East. On 28 September 1914, they sailed for England, arriving in Liverpool on 22 October, then spent almost two weeks training and refitting at Winchester in southern England. On 5 November, they embarked from Southampton and landed in Le Havre later that night with a total strength of 31 officers and 1,019 other ranks.2

At 9pm on 15 November, the 1st RIR went into the front-line trenches for the first time, near a town in northern France called Laventie, roughly 30 kilometres south of Ypres, which lay across the border in Belgium. They immediately came under artillery fire and before midnight, had already lost two men killed by German snipers. Over the course of seven days spent on the front line, the battalion had a casualty list of 41 NCOs and Riflemen killed, wounded or missing, most falling victim to snipers.3

Despite his years of experience, Barnes was not a model soldier. On 20 November, only five days after going into the trenches, he was brought before a Field General Court Martial at Laventie, charged with “putting the success of an operation at risk.”4

The precise nature of what Barnes had done to endanger an operation is not known, but it most likely relates to an incident two nights previously, on the night of 18/19 November. The battalion had received a report that the German VII Corps facing them had vacated their trenches, so patrols were sent out to investigate but “found that the German trenches were actively held. The battalion lost one Rifleman (Dempster) missing and believed killed on this reconnaissance.”5

British Army Field Punishment Number 1

Barnes was found guilty and sentenced to three months’ Field Punishment Number 1. This did not involve the soldier being detained in a military prison – instead, he would remain with his unit but be bound hand and foot in irons or with ropes and tied to a fixed object, such as a post or the wheel of a gun or cart. He would be left there for two hours a day and then resume his normal duties.6

However, Barnes did not serve his full sentence. Within days of his court martial, he received a gunshot wound through his right arm. The wound was evidently severe enough to warrant him being shipped back to England as, on 25 November, the Belfast News-Letter reported that “Rifleman Patrick Barnes, Royal Irish Rifles, who was shot through the right arm, is now in the military hospital at York.”7

Barnes never returned to France. On 14 May 1915, he was discharged from the army under King’s Regulations paragraph 392 xvi, which meant he was no longer physically fit for active service.8

His wound entitled him to receive the Silver War Badge, which was awarded to all military personnel who were discharged due to sickness contracted or wounds received while serving in the war. This was one of four medals that Barnes received. He was also given the “Mons Star,” a campaign medal awarded to all British troops who had served on the Western Front up to late November. At the end of the war, he got the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. For a soldier who had not even spent ten days on the Western Front, it was a remarkable haul.9

Patrick Barnes was awarded (L-R): the Silver War Badge, Mons Star, Victory Medal and 1914-1918 War Medal

After coming home to Belfast, he joined the Irish Volunteers.

1916: the Easter Rising

The Irish Volunteers started organising in Belfast in March 1914 on the initiative of members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). They had a dual system of control: a Civil Committee, chaired by Denis McCullough, and a Military Committee, led by Peter Burns. Burns was assisted in training the Volunteers by Seán Cusack, a serving British soldier, and by Seán O’Neill and Rory Haskin, both former soldiers; Haskin was also a one-time member of both the Orange Order and the Ulster Volunteer Force but had been persuaded to join the IRB. McCullough was the overall commander.10

The organisation was soon swollen by an influx of non-republican recruits:

“At the beginning recruitment was slow but due to some sudden change in policy and the word received by the UIL [United Irish league] and AOH [Ancient Order of Hibernians] branches we were shortly flooded out by members until at the peak point the Belfast regiment must have numbered between four and five thousand.”11

Irish Volunteers on the Falls Road in 1915 (Irish News, 19 March 2016)

At the outset of the Great War, in common with the rest of the country, the Volunteers in Belfast split, with the majority following John Redmond to form a new force, the National Volunteers. However, the enthusiasm among those who adhered to Redmond and his Belfast acolyte Joe Devlin soon dwindled:

“On the following Saturday when the Devlinite Volunteers paraded to march to the GAA park for drill purposes it was found that the 3,000 had dwindled to 1,600. On the next Saturday the 1,600 had dwindled to 1,200. Eventually this body numbered 400 and their public parades were disbanded. Many of these Volunteers were soon recruited by the Irish Party into the British Army and fought in the 1914-1918 War.”12

Meanwhile, according to McCullough, the Irish Volunteers “were left with less than a hundred and fifty all told.”13

As part of the Military Service Pensions process in the 1930s, a nominal roll was drawn up of members of the Belfast Battalion of the Irish Volunteers in 1916. At that point, numbers in the battalion had inched up to 163, one of whom was Barnes.14

In January 1916, McCullough attended a meeting with Patrick Pearse and James Connolly in Dublin, accompanied by a Dr Burke who was to be the overall military commander in Ulster for the Rising then being planned. The Belfast Battalion was to mobilise in Tyrone and then, along with the Tyrone Volunteers, to march to Galway to link up with the forces under Liam Mellows who would be leading the insurrection there.

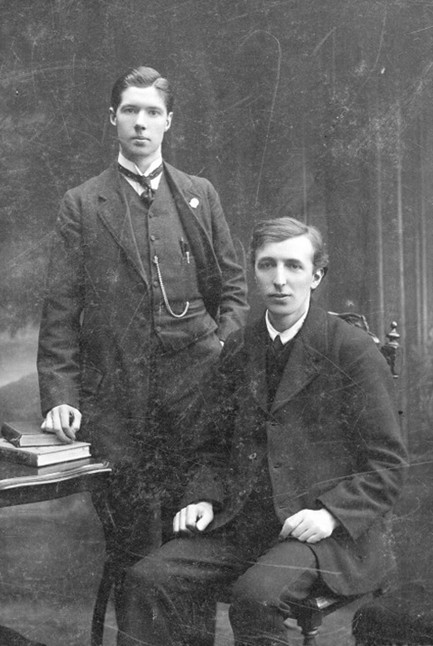

Denis McCullough (standing) and Bulmer Hobson were senior members of both the IRB and the Irish Volunteers

McCullough had reservations about the plan:

“I pointed out the length of the journey we had to take, the type of country and population we had to pass through and how sparsely armed my men were for such an undertaking. I suggested that we would have to attack the RIC [Royal Irish Constabulary] barracks on our way through, to secure the arms we required. Connolly got quite cross at this suggestion and almost shouted at me ‘You will fire no shot in Ulster: you will proceed with all possible speed to join Mellows in Connaught [sic]’ and, he added, ‘If we win through, we will then deal with Ulster.’”15

On the Monday of Holy Week, McCullough was in Dublin, where he confronted Seán McDermott and got him to admit that the plan was to stage the Rising on Easter Sunday. McCullough returned to Belfast, where he spent the rest of the week making local preparations:

“We bought a lot of light equipment from the Ulster Volunteer stores which was distributed amongst the men who we instructed to bring two days’ rations and any small arms and ammunition they had with them. The forty odd rifles we had, of mixed age and vintage and the ammunition for them, Peter Burns and his helpers brought out of the city to the house of a man named Stewart … where they would be available for transport to Tyrone.”16

The Belfast Volunteers were split into three groups, under the leadership of Burns, Cathal McDowell and Archie Heron. Each group made their separate way by train to Dungannon, their fares paid by McCullough, then marched to Coalisland, where they were billeted on Easter Saturday night.17

St Patrick’s Hall in Coalisland, where the Belfast Volunteers were billeted on Easter Saturday night

But while the men were bedding down, their leaders were paralysed by confusion. McCullough had gone to Tyrone a day ahead of his men but when he got there, he found the local leadership having second thoughts:

“On my arrival at Carrickmore, I found gathered in the McCartan home, Dr Patrick McCartan, Father Daly CC, Father Coyle CC and Burke the organiser…They expressed the opinion – particularly the priests and also Burke – that the whole thing was engineered and inspired by Connolly; that it was not a Volunteer, but a socialist rising; that it had no sanction etc from MacNeill. I informed them of all I knew and of what I had learned from Sean McDermott on my visit to Dublin.”18

Further discussions followed on Easter Saturday, which ended with McCullough insisting that the Belfast contingent would go ahead with the Rising as ordered, with or without the locals: “I issued an ultimatum to these men in Tyrone that if they did not carry out the instructions which I had received and they had received, I was prepared to take my men through the country.”19

The arrival of a courier from Dublin in the early hours of Sunday morning, bringing Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order calling off the Rising, injected further chaos at a time when discipline was starting to break down. McDowell recalled that,

Ormeau Road mural commemorating Cumann na mBan sisters Nell and Elizabeth Corr who mobilised for the Easter Rising; their brother was killed in the Battle of the Somme

“Denis McCullagh [sic] informed me that he was in supreme command of the Belfast men and that he was obeying the countermanding orders, and that I must obey his orders, as he was my superior officer. I told him that as he was in charge in a civil capacity, and as Peter Burns was the officer in charge during military operations, that Burns was the competent authority to issue military orders to me. Mr McCullagh informed me then that Peter Burns was not in a state capable of issuing orders as he was intoxicated.”20

Adding an element of farce to an already unravelling situation, McCullough himself inadvertently disobeyed Connolly’s strict instructions that not a shot was to be fired in Ulster:

“I took out the small automatic to examine it. I was fool enough to pull the trigger to ascertain if it was loaded – it was, and the bullet went through my left hand, breaking no bones, but leaving a large gap where it passed out. I don’t remember what happened then. I suppose I must have passed out, because I came to, sometime later, lying on the side of the ditch.”21

Unsurprisingly in hindsight, one Belfast Volunteer lacked faith in the military abilities of his officers and opted to make his way to Dublin instead. Joseph Connolly said, “I believed we would be ‘wiped out’ and that if such were to be the case, I as a private ranker in the Volunteers preferred to take my chances under reasonably reliable leadership.” Having arrived in Dublin, Connolly met with MacNeill and was sent to bring the countermanding order to the Volunteers in Drogheda.22

When the Belfast Volunteers returned from mass on Easter Sunday morning, McCullough told them to march to Cookstown. The rank-and-file were bewildered, as Henry Corr explained:

“None of us knew where we were bound for, nor what was happening. We were under the impression that we were bound for Dublin, but no one told us anything. On boarding the train at Cookstown we were handed our railway tickets and found they were for Belfast. This was the first time we knew where we were going. We had no choice in the matter, as we were not asked either to fight or go home.”23

News that the Rising had gone ahead on Easter Monday reached Belfast the following day and some of the Volunteers decided to try to take part – David McGuinness recalled in relation to Archie McLarnon, who was a taxi driver: “Returning home from Cookstown on Easter Monday 1916, applicant, myself and three others endeavoured to get through to Dublin in his car but we were forced to return by police road patrols outside Lisburn.”24

Others made even more desperate, if equally futile, attempts – Patrick Fox said of Daniel Braniff, “on [his] return from east Tyrone with Belfast contingent, he with Cathal O’Shannon walked to Dublin but arrived too late to participate in fighting.”25

The burned-out shell of the GPO in Dublin after the Easter Rising

In the wake of the Rising, many of the leadership of the Belfast Volunteers, among them McCullough, Burns and Haskin, were arrested and interned in Frongoch in Wales, not being released until the following August. Even this process had its moments of black comedy, as Frank Booth recalled:

“On one raid on Tom Wilson’s premises, where he carried on a butchering business, they captured an old type of machine gun. This weapon was constructed with a lot of brass mountings. It was a most complicated piece of mechanism. When the RIC took it to the barracks some of the police officers, after examination, said it not was not a machine gun but a sausage machine and told the men who took it to leave it back at Wilson’s place again.”26

There is no specific mention of Barnes in any of the archival records relating to the Rising, other than a handwritten note by Burns at the end of the nominal roll, stating that “the above were all members of the Belfast Volunteers Batt. on Easter Week 1916.” From that, it is clear that Barnes mobilised in Coalisland with the others and shared the same confused experience as them.27

His next battle would not come until 1920 – it was not a military one, but an electoral one.

1920: Belfast Corporation election

In January 1920, Barnes fought a new kind of battle when he went forward as a Sinn Féin candidate in the elections for Belfast Corporation, nominated by McCullough and seconded by Connolly.

He stood in the St Anne’s ward which encompassed the city centre as well as an area extending towards southwest Belfast, bounded by the Grosvenor and Falls Roads and by Milltown Cemetery, but also taking in Broadway, the Village and Sandy Row. Prior to the election, the proto-fascist British Empire Union (BEU) demanded that all candidates answer three questions:

“Will you, if elected, undertake:

- To give no tender or contract to any firm connected directly or indirectly with the late enemy powers

- To give preference in accepting tenders or giving contracts to British firms employing British labour (preferably local firms employing local labour)

- To give preference in municipal employment to ex-servicemen?”28

Most candidates replied “satisfactorily” to all three questions. However, Barnes’ pugnacious answers to questions 1 and 3 were deemed “unsatisfactory” and held up for the disapproval of electors in a prominent BEU advertisement published in the unionist press: “1: We know no foreign enemy power only England. 3: Provided these ex-servicemen served under the Irish Republican Army.”29

The election was held under PR. When the votes were counted, the quota was set at 1,357 and with six seats to be filled, Barnes was in with a chance, coming in seventh. More significantly, he got twice as many votes in the first count as his nationalist rival, Frank Harkin of Devlin’s Nationalist Party:

- Alex Boyd (Independent Labour) 1,627

- George Donaldson (Belfast Labour) 1,117

- James Doran (Unionist) 1,096

- Hugh McLaurin (Unionist) 1,017

- Alex Hopkins (Ulster Unionist Labour Association) 945

- James Johnston (Unionist) 860

- Patrick Barnes (Sinn Féin) 828

- F. Curley (Independent Unionist) 577

- Frank Harkin (Nationalist) 410

- R.M. Gaffikin (Unionist) 405

- C.A. Hinds (Unionist) 361

- Matthew Shields (Liberal) 92

- Charles Corrigan (Belfast Labour) 84

- John Shaw (Belfast Labour) 83

- George Park (Independent) 58

After the seventh count, which involved the distribution of Harkin’s transfers, Barnes’ total stood at 1,117 votes. However, McLaurin took the last seat without reaching the quota, pipping Barnes by just 129 votes.30

Emmet O’Connor has noted that while two Labour candidates topped the poll, they were far from Connollyite in outlook: “The two Independent Labourites were unionist on the Home Rule question, as was Alex Boyd … both Boyd and Donaldson would endorse the workplace expulsions in 1920.”31

City Hall: Patrick Barnes was narrowly beaten in the 1920 election of councillors to Belfast Corporation

1920-1922: the Pogrom

At some point in 1920 – it is not clear exactly when – Barnes joined the IRA. At the time of the election, he had been living at 32 Dunmore Street in Clonard, so he joined B Company, 1st Battalion, which drew most of its recruits from that area, the Springfield Road and Beechmount.32

As a former British soldier with over six years’ service, his military experience was invaluable to the IRA, especially from a training perspective; however, there is little detailed information available about the specifics of his activities in the initial part of the Pogrom.

But by the end of 1921, Barnes was, if not the official Quartermaster of B Company, certainly acting in that capacity. For a supposedly secret underground revolutionary army, the IRA had a ridiculous habit of keeping extensive written records. During the October 1922 capture of an IRA arms dump at 15 Dunmore Street, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) discovered documents, including a detailed list of B Company weapons issued and received back.33

The documents list the date, name of the recipient, type of weapon, quantity of “stuff” (ammunition), who it was issued by, to which post, who it was received back by and when. The initials PB feature repeatedly as the person issuing weapons.

The documents cover a period of almost three weeks from 12-31 December 1921 and provide useful insights into the activities of B Company at that time.

Captured list of B Company weapons issued and by whom (© PRONI, HA/5/655 Seizure of cache of arms in Belfast and prosecution of James and Patrick Doherty and Edward Kane; reproduced by permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

Firstly, the company had a motley assortment of weapons. Most were handguns or revolvers, with several Mauser “Peter the Painter” semi-automatic pistols. B Company also had a variety of rifles – Lee Enfields, Steyrs and Martinis.

Most of the weapons were issued to outposts at the end of Clonard closest to Cupar Street, which marked the boundary between nationalist Clonard and the unionist Shankill area – in Lucknow Street, Kane Street and Kashmir Road; the repeated references to “McErlean’s” in the documents are to McErlean’s spirit grocery at 49 Clonard Gardens, on the corner of Bombay Street. It was from this direction that loyalist incursions were most likely to come and where pickets were stationed. Defending against such attacks was clearly B Company’s main priority at this stage.

Clonard during the Pogrom (OSNI Historical Fifth Edition 1919-1963, © Crown Copyright, OSNI, Licence no. 3036)

By 1922, Barnes was living at 84 Cullingtree Road in the Lower Falls, where he also had a shop that sold second-hand clothes bought at auctions. He was transferred from B Company to become the Captain of E Company, 1st Battalion, which was largely based in that area. In May, the IRA launched its “northern offensive,” part of which entailed a widespread arson campaign directed at unionist-owned business premises.

He was particularly active in the offensive: “Believed to have been concerned in bomb-throwing at Albert St 20/21-5-22 … organised burning of tram at Divis St 24-5-1922, also a similar outrage at Donegall–Falls Road crossing on same date.” In relation to the bomb attack, the police report of incidents on 21 May notes that, “At 10pm, two bombs were thrown at 42 Albert Street, the residence of Mrs Sarah McIlroy, 60 years, chemist (P [Protestant]). One exploded on footpath and the second on the road. No damage done except glass was broken.” As well as attacks on the police and unionist-owned businesses, the campaign also involved sectarian attacks on elderly women.34

In the Donegall Road incident, eight armed men held up the driver and conductor of a tram at the very top of the road, sprinkled paraffin and set the tram on fire, then released the brake to send it down the hill in the direction of Broadway, gathering speed as it went. A passerby pulled down the trolley wire, bringing the blazing tram to a stop just after Celtic Park football stadium.35

Firemen tackling the aftermath of an IRA arson attack, May 1922

On 26 May, Barnes led an arson attack on a factory in Hastings Street off Divis Street, one of seventeen such attacks that day. The following morning, the press reported:

“The most serious conflagration took place in the promises of Messrs George Monro Ltd, hemstitchers and embroiderers, Hastings Street, the entire building being gutted and all the valuable machinery and stock destroyed … The firemen got to work on the ground floor but it was no easy task coping with the flames, and for an hour the most strenuous efforts seemed of no avail. Flames leapt high into the air and volumes of smoke poured from the windows and interfered with the task of fighting the flames, but the firemen refused to be beaten, and after a couple of hours succeeded in getting the flames under control. By this time the building in which the fire originated was a heap of smouldering ruins.”36

Hugh Corvin, who had been the Quartermaster of the 1st Battalion prior to the IRA split in the spring of 1922, said that “The burning of the factory referred to was carried out by the ‘Free State side’ – there were special incendiary bombs sent from Dublin.”37

However, during this attack, Barnes sustained an injury that was to have severe consequences for him a few months later: “Testicles injured through falling stride-legs on a plank…Whilst retreating from the factory yard by crossing the wall he slipped on a plank which they were using as a kind of ladder.”38

Undaunted, Barnes continued to take on more operations. A week after the Hastings Street attack, the police believed that “He was instrumental in burning the Model School.” This was the third arson attack on the Protestant school, which was in Divis Street – the final attack on 2 June left only a gutted shell.39

The remains of the Model School in Divis Street after a third IRA arson attack (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 3 June 1922)

1922: the IRA split and the Curragh

At the start of July 1922, Barnes was still in Belfast.

In the nominal rolls for 1 July 1922 drawn up in the 1930s, the entire 3rd Northern Division still in the north was described as “Executive Forces” (meaning anti-Treaty), with Patrick Thornbury rather than Séamus Woods named as O/C 3rd Northern Division; William Ward, not Roger McCorley, was O/C Belfast Brigade; Patrick Nash, not Seán Keenan, was Vice O/C. Barnes was included in the nominal roll for the merged C and E Companies, 1st Battalion, in effect meaning that at that date, the anti-Treaty IRA viewed him as one of their members.40

However, as detailed in a previous blog post, members of the Belfast Brigade began fleeing south over the course of the summer to avoid internment, which was introduced on 23 May. Barnes joined them.

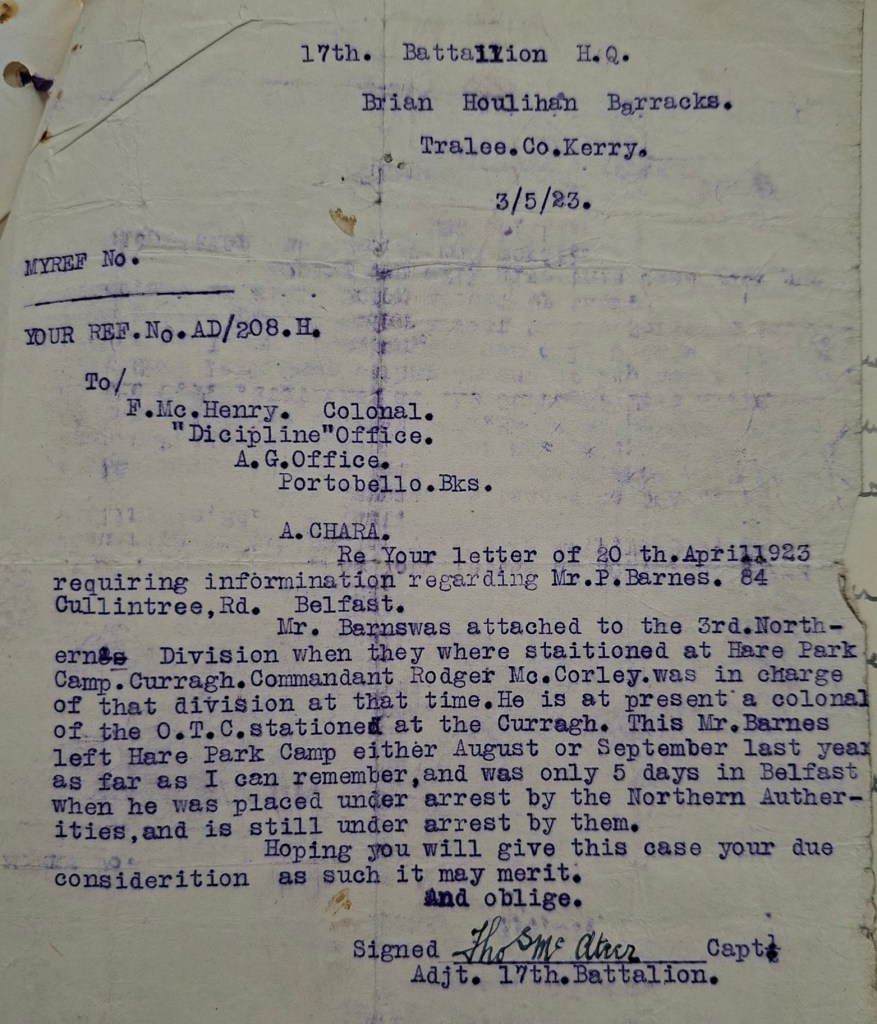

They were offered a barracks in the Curragh in Kildare, ostensibly to train for a new offensive against the northern government. In a subsequent application for a Military Service Pension, Barnes said he was “Drill Instructor at Curragh Camp.”41

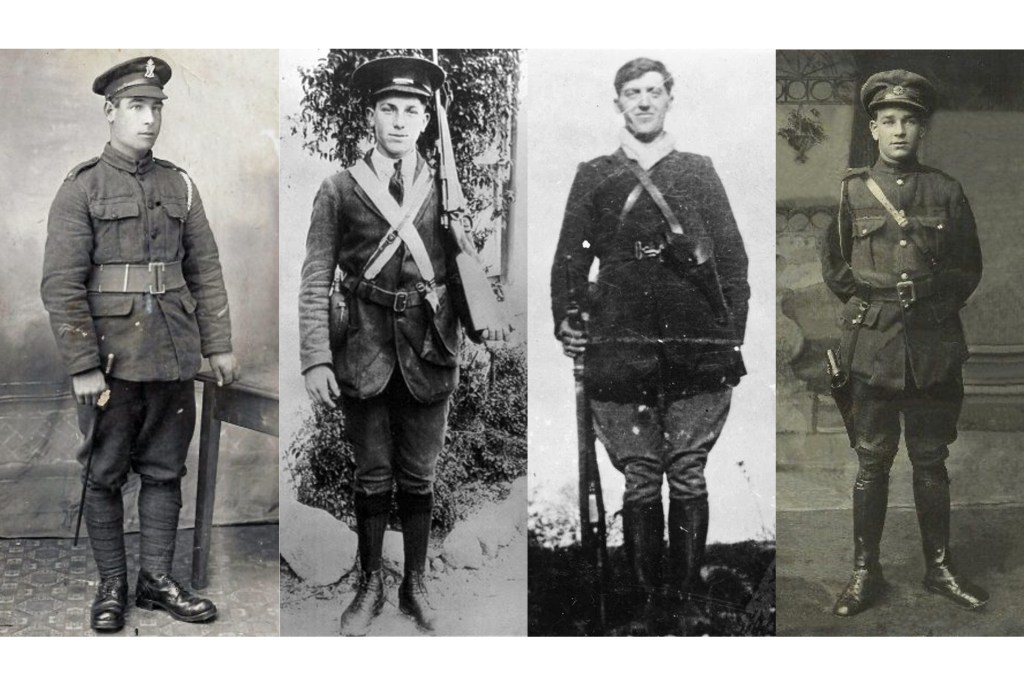

Barnes’ claim was corroborated by a memo sent by the Adjutant of the 17th Infantry Battalion of the National Army, a unit largely made up of former 2nd and 3rd Northern Division members: “Mr Barnes was attached to the 3rd Northern Division when they were stationed at Hare Park Camp, Curragh.” As a photo exists of another Belfast Brigade member, James Cassidy, wearing National Army uniform in the Curragh during the summer of 1922, it is likely that Barnes was similarly outfitted.42

The RUC were also aware of his whereabouts at that time. Although he had been earmarked for internment on account of his activities during 1922, a police file noted that “He is believed to be at present with the IRA on the Curragh.”43

But at the end of August, Barnes made the fateful mistake of going back to Belfast. Based on information obviously supplied by an informer, an RUC Sergeant based in Cullingtree Road Barracks filed a report:

“… a meeting of the above unlawful organisation was held at 9pm on Sunday 20th inst at Carberry’s Yard 90-92 Albert Street. There were about twenty-five members present and they were addressed by Patrick Barnes, Cullingtree Road, and others … Barnes is an ex-soldier and is a well known Sinn Feiner. He is known locally as ‘Mick Collins’ because he escaped so often from the police and military. His house was raided time and again but we could never find him at home. He acted as Sinn Fein policeman in this district…I was also informed that this man guided & directed the fire-bugs operating in the city.”44

The following month, the RUC finally caught up with Barnes.

1922-1923: internment

Barnes was arrested on 19 September at 12 Inkerman Street in the Lower Falls, in what was presumably an IRA safe house; he almost evaded capture again – “By the time the police were admitted he was putting on his boots in the kitchen.”45

He was initially held in Crumlin Road Gaol but was sent for internment on the SS Argenta on 2 October.

However, a week later he was sent back and admitted to the prison hospital, where he was placed in the care of Dr. P. O’Flaherty. The injury sustained in the Hastings Street arson attack had flared up and he was diagnosed as having a hydrocele – a swelling of the scrotum due to a build-up of fluid beneath the skin. The doctor was concerned about the possible presence of cancer: “If it is an ordinary hydrocele there is no need to take any further action, but the case is not quite clear & it may possibly be malignant, in which case he should be operated on as soon as possible.”46

Barnes initially refused to allow the doctor to take a sample of the fluid for analysis, going as far as to pull out a tube the doctor had inserted for the purpose on 18 October. However, five days later, as his pain increased, Barnes relented and agreed to let the doctor perform the procedure under anaesthetic.47

Victoria Barracks, where Patrick Barnes underwent a life-saving operation (© National Library of Ireland, Lawrence Collection)

The fluid sample largely consisted of blood but also confirmed the presence of a tumour, which further alarmed the doctor, so on 2 November, Barnes was transferred to the military hospital at Victoria Barracks on North Queen Street, where the army’s medical staff had agreed to perform an operation. There, on 6 November, Barnes’ right testicle was removed; a subsequent laboratory examination of the tumour confirmed the presence of a sarcoma, or malignant cancer. The British Army had saved Barnes’ life.48

After a period of recuperation, Barnes was returned to the prison hospital and then to internment – not on the Argenta, but in Larne Workhouse, another internment centre, which Dr. O’Flaherty felt would be “preferable” given Barnes’ recent operation.49

Having won his medical battle with the help of his political enemies, Barnes then embarked on his final campaign – to secure his release from internment.

While in the prison hospital, he had written to the Ministry of Home Affairs, citing his illness, protesting his innocence and highlighting his service in the British Army: “I am a man with a good character has never been in prison and has served in the 1st Battalion Royal Irish Rifles … I was wounded at the Battle of Ypres through my right arm and was discharged with a good character.”50

On 12 December, he appeared before the Advisory Committee which adjudicated on internees’ appeals for release. His was rejected. In what was to become an almost-monthly cycle, he wrote three more petitions for release to the ministry in the early part of 1923 – each was turned down, including one decision which Barnes appealed.51

Larne Workhouse, which was used as an internment camp

For his fourth petition, Barnes shifted his strategy away from his own innocence and his wife’s ill health to being a member of the Free State, or National, Army to which he wanted to return: “I am quite willing to rejoin my camp again in Curragh.”52

On 8 May, he was given another hearing with the Advisory Committee – this time, he had new ammunition:

“I here enclose a communication from General Mulcahy. I came down from Curragh Camp to undergo an operation. Then I was put under arrest, for what reason I cannot state … Whilst at home I was never in any illegal organisation or otherwise. I am quite willing to rejoin the camp again at the Curragh.”53

The letter in question was from the Free State Minister for Defence and National Army Commander-in-Chief, Richard Mulcahy, to Barnes’ wife, saying that he was “having the case looked into.” However, the Advisory Committee once more turned down Barnes’ application.54

To support his next petition, Barnes enclosed a memo from the 17th Infantry Battalion of the National Army, confirming that he had been stationed in the Curragh. Officials in the ministry decided to ignore this: a Major Shewell noted, “As the FS authorities have never written officially to us about Barnes, I do not think that much importance need attach to this communication;” Henry Toppin concurred: “The usual letter that he cannot be released will suffice.”55

Another petition followed in June and met with predictable results, as did Barnes’ appeal against the decision. A third appearance in front of the Advisory Committee on 6 July was no more fruitful.56

Memo from National Army, confirming that Patrick Barnes had been stationed at the Curragh (© PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick, Cullingtree Road, Belfast; reproduced by permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

In his next petition in July, it emerged that Barnes might now be facing a new battle on a different front:

“I have decided to sell out my business in Belfast and cross the border … as I am not feeling too well owing to having undergone an operation and also to domestic trouble at home I have come to above decision of going to Free State as I see no hope of release otherwise.”57

Later that month, his nephew Robert applied to visit Barnes, but the ministry decided to check first with the police: “He states that he…wishes to see him in connection with … a private family matter the nature of which cannot be disclosed, but it is a matter of the family name being at stake and it is not in any way connected with politics.” Barnes’ brother-in-law appealed to the ministry to forbid the visit: “He states that Robert Barnes is only looking for this visit in order to stir up trouble between Patrick Barnes and his wife, by telling him about her…There is no domestic trouble in the case.”58

The RUC in west Belfast were asked to investigate and reported:

“Latterly it has been rumoured that Mrs Barnes has been friendly disposed to another man, but the police are unable to get verification of this rumour. It is assumed this is the family matter referred to in applicant’s letter and it is thought that the real object of the intending [sic] visit would be to give the internee all the information in circulation re this matter which would probably cause domestic trouble.”59

Not wishing to aggravate Barnes, the authorities refused permission for the visit.

An internee’s drawing of Larne Workhouse Internment Camp (© National Library of Ireland, Ms 42,784 Autograph book of Irish Republican prisoners; reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

By the autumn, not alone were Barnes’s petitions still being routinely rejected, even his requests to once more see the Advisory Committee were also being refused: “no purpose would be served by bringing him before the Advisory Committee again at present.”60

1923: release

Barnes was the not the only internee frustrated by a litany of rejected petitions for release and failed appearances at meetings of the Advisory Committee.

On 25 October, the accumulated anger boiled over when almost 200 internees on the Argenta began a hunger strike demanding unconditional release; they were soon joined by 89 others in Larne Workhouse. To weaken their mutual support, 65 of the Larne hunger strikers were transferred to prisons elsewhere, with 40 sent to Derry and the remainder to Belfast.61

“Violence broke the sombre cloud over Larne Camp on the 1 November as the warders attempted to segregate the strikers from the non-strikers by ordering the removal of their belongings and beds to another division of the building. A near riot situation erupted … [Governor] Drysdale was informed of the situation and ordered Captain Richardson and his Specials to move in with the authority to forcibly remove those who offered resistance.”62

The cumulative medical effects of starvation, coupled with the imposition of segregation and isolation, meant that men gradually began to come off the hunger strike by early November. With one exception in Derry who held out an extra day, the final 56 men who were still refusing food gave up on 11 November, the seventeenth day of the strike.63

The failed hunger strike had a consequence for Barnes, although not one that might have been expected.

On 5 November, the Governor of Larne Internment Camp, A.D. Drysdale, wrote to the Ministry of Home Affairs about the conduct of eight internees, among them Barnes: “The others named have been conspicuous in affording the staff their support in a most difficult time, and I think it right to direct your attention to the fact … The example of these men has helped others who were wavering to resist the pressure brought to bear on them to join the hunger strike.”64

The ministry asked Charles Wickham, the Inspector General of the RUC, “to report with the least possible delay whether you are of the opinion that release could safely be granted on any conditions. The Minister considers that in considering the cases great weight should be attached to their conduct during the hunger strike as reported by the Governor.” Wickham then told the Belfast City Commissioner, John Gelston, “unless there are strong reasons to the contrary, these men should now be given an opportunity to show that they can behave as well outside the Internment Camp as they have done inside it.”65

Gelson took the hint and recommended release on £100 bail, with two independent sureties of £50 each. Civil servants in the ministry then accelerated the process by recommending to Richard Dawson Bates, the Minister of Home Affairs, that Barnes be released without the formality of an appearance at the hated Advisory Committee. Bates assented and the necessary sureties were soon provided by two Cullingtree Road publicans.66

On Christmas Eve 1923, after over fifteen months, Barnes was released from internment.

An internee dreams of release (© National Library of Ireland, Ms 42,784 Autograph book of Irish Republican prisoners; reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Having been wounded in the Great War, he was entitled to a pension from the UK War Office and there are records that suggest he was in receipt of one at least as late as October 1920. However, his internment by the Government of Northern Ireland – and more specifically, the reasons for it – would most likely have disqualified him from receiving future payments. But there was a peculiar coda to this: a pension ledger card for Barnes is clearly marked “Dead” and dated 13 February 1924, just seven weeks after his release. Was Barnes, or someone acting on his behalf, finally severing his last connection to the Royal Irish Rifles?67

Pension ledger card for Patrick Barnes, marked “Dead” and dated 13 February 1924 (© Royal Ulster Rifles Museum, Belfast)

Afterlife

After his release, the very much not-dead Barnes applied for a Military Service Pension under the southern Military Service Pensions Act 1924. Curiously, he did not claim for any service during the Easter Rising. However, he did say that he had been at the Curragh and having gone home to Belfast for an operation, had been interned. Barnes’ application form was not signed by any witness, which may have contributed to the decision of the Board of Assessors not to recognise any service for any period.68

He kept his shop at 84 Cullingtree Road going, but by 1932 it had become a fruit and vegetable shop – he was described as a “fruiterer” when he appeared as a witness in the trial of a man accused of stealing a clock from a Presbyterian church in Regent Street. The thief had asked Barnes to buy the clock, but he had declined. The man left the clock with Barnes anyway but never returned to collect it – Barnes must have brought it to the police rather than risk being accused of acting as a “fence.”69

Barnes moved around the corner to 34 Albert Street the following year. If his shop had gone out of business, that may have been what prompted him to apply for a Wound Pension under the Army Pensions Act 1932.70

This was another curious application.

When asked on the form if he had applied under the Military Service Pensions Act 1924, he said he had but “received no reply;” but when asked if he had ever served with a range of military and police forces, including the British Army, he said he had not. In other words, he denied ever having been in the Royal Irish Rifles – in his mind, 8937 Rifleman Barnes no longer existed.71

As part of their investigation of this claim, the Military Service Registration Board set out to establish afresh whether Barnes had been in the IRA, and having received reports from several of his former superior officers, decided that he had. While this investigation was in progress, the authorities in Dublin noted that Barnes had moved house again, this time to 23 Annadale Street off the Antrim Road in north Belfast.72

Despite the evidence of his officers as to how Barnes had been injured in the Hastings Street operation and the provision of the medical records of Dr. O’Flaherty in Crumlin Road Gaol by the UK’s Dominions Office, the Department of Defence eventually decided that “You did not receive any wound or injury while engaged in military service.”73

But Barnes received no reply to this application either. The rejection letter was sent to his old address in Albert Street and a week later, was returned to Dublin, unopened and marked “Gone away.”74

Summary

By 1939, Barnes had moved from 23 Annadale Street – the 1939 Belfast Street Directory shows that somebody else was living there at that stage. In April 1941, Annadale Street suffered extensive bomb damage in the Belfast Blitz, with seventeen residents of the street killed. Barnes had again escaped being killed by the Germans, having been wounded by them in 1914.75

His military career in the intervening years was that of a chameleon.

His extremely brief time on the Western Front in 1914 highlighted the fact that while he had six years’ experience as a trained soldier, he had zero combat experience. He was no different from most of his comrades in that respect, but he was the one who was sentenced to Field Punishment Number 1 within five days of the 1st RIR going into the front line. This humiliating treatment would have reduced his fellow-soldiers’ respect for him and alienated him from them and from the wider British Army. From that point of view, the war-ending wound that sent him back to England a few days later was perversely fortunate in timing. He had every motive to later write 8937 Rifleman Barnes out of history via the pension ledger card and his Wound Pension application.

Joining the Irish Volunteers gave him the opportunity to replace going to war for Britain with going to war against Britain. But the Easter Rising as it took place in Coalisland was a fiasco of unfulfilled hopes. All Barnes got to do was to take the train with the other Belfast Volunteers, sit around for two days while his officers tried to figure out what was happening and what to do about it, then take the train back to Belfast: not a memory to cherish proudly and one that was easy to omit from his Military Service Pension application.

By the time of the 1920 Belfast Corporation election, he had swapped ineffectual republicanism for a more trenchant, combative kind – ironically, adjectives that echo the Western Front. This was expressed politically as a Sinn Féin candidate in the election but militarily as an IRA member during the Pogrom.

By late 1921, he was an important and active figure in B Company of the 1st Battalion if, as is most likely, the initials PB in the captured arms documents refer to him. As 1922 progressed, after being promoted to take command of E Company, he led several notable operations during the “northern offensive,” pointing to his increased standing within the IRA. Now, at last, he had become the soldier he always wanted to be. The bomb attack on the house of the 60-year-old Protestant woman is a reminder that this was not always a noble endeavour. Equally, his junior leadership position is a reminder that the IRA did not just accept former British soldiers as members, it valued and rewarded their contributions.

In the post-split chaos of the summer of 1922, there were two 3rd Northern Divisions of the IRA, one loyal to the Army Executive in the Four Courts, one reporting to the pro-Treaty GHQ in Beggars Bush Barracks. Each claimed Barnes as a member, one while he was still in Belfast, the other after he went to the Curragh.

The unionist government was not interested in the distinction, as Barnes discovered after being interned – to them, he was just another IRA member to be locked up. It is an irony that just a month after being sent to the Argenta, Barnes was back in the hands of the British Army, this time for a life-saving operation. When sent to Larne, he soon learned that his Great War medals were of no avail as he went through the morale-sapping saga of futile petitions and Advisory Committee appearances.

His role in the October 1923 hunger strike was his last and possibly most surprising change of skin. The man who had released the brake on the burning tram on the Donegall Road now acted as a brake on fellow-internees joining the hunger strike. It was a volte-face that brought about his release and maybe the lessons he drew from that were what prompted him to bring the stolen clock to the police in 1932.

If, to while away the time, the internees in Larne had been tempted to play revolutionary-era bingo, Barnes would have been the only one to exclaim “Full house!” I know of no-one else who had successively been in the British Army, the Irish Volunteers, the pre-split IRA, the IRA “Executive Forces”, the 3rd Northern Division contingent at the Curragh (and possibly by extension, the National Army), an internee on the Argenta and in Larne Internment Camp. Others had been in several of those, but not all of them.

But after the many armies he had been in, all Patrick Barnes had left to show for it was four medals, one testicle and no pension to help him through life under partition.

References

1 Census of Ireland, 1901; Roll of Individuals entitled to the “War Badge,” 18 November 1916, Royal Ulster Rifles Museum, Belfast (RURM).

2 Patrick Barnes to Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), n.d. [October 1922], Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick, Cullingtree Rd, Belfast, (hereafter Barnes, Patrick); The National Archives (TNA), WO 95/1730/4 War Diary, 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles.

3 TNA, WO 95/1730/4 War Diary, 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles.

4 Information supplied to author by RURM, 4 November 2025.

5 TNA, WO 95/1730/4 War Diary, 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles.

6 Information supplied to author by RURM, 4 November 2025.

7 Belfast News-Letter, 25 November 1914.

8 Roll of Individuals entitled to the “War Badge,” 18 November 1916, RURM.

9 TNA, WO 329/2476 Medal Roll for 1914 Star & WO 329/1673 Medal Roll for British War Medal and Victory Medal.

10 Military Archives (MA), Bureau of Military History (BMH), WS0223 Rory Haskin.

11 MA, BMH, WS0124 Joseph Connolly.

12 MA, BMH, WS0183 Liam Gaynor.

13 MA, BMH, WS0915 Denis McCullough.

14 Belfast Battalion, Irish Volunteers, 1916, MA, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), RO/402 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast) GHQ.

15 MA, BMH, WS0915 Denis McCullough.

16 Ibid. The reference to the Ulster Volunteer Force stores is not a mistake – in his BMH statement, Rory Haskin said that the Belfast Volunteers even bought Steyr rifles from the Ulster Volunteers and Lee Enfield rifles from British soldiers.

17 MA, BMH, WS0577 Archie Heron.

18 MA, BMH, WS0915 Denis McCullough.

19 Sworn statement to Advisory Committee, 19 April 1940, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF55173 Denis McCullough.

20 MA, BMH, WS0173 Cathal McDowell.

21 MA, BMH, WS0915 Denis McCullough.

22 MA, BMH, WS0124 Joseph Connolly.

23 MA, BMH, WS0277 Henry Corr.

24 David McGuinness to Board of Assessors, 1 December 1925, MA, MSPC, 24SP10337 Arthur McLarnon.

25 Patrick Fox to Military Service Pensions Board, 27 August 1936, MA, MSPC, MSP34REF6164 Daniel Branniff.

26 MA, BMH, WS0229 Frank Booth.

27 Peter Burns note re Belfast Battalion, Irish Volunteers, 1916, n.d., MA, MSPC, RO/402, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast) GHQ.

28 Belfast News-Letter, 13 January 1920.

29 Ibid.

30 Belfast News-Letter, 19 January 1920.

31 Emmet O’Connor, Rotten Prod: The Unlikely Career of Dongaree Baird (Dublin, UCD Press, 2022), p34.

32 Patrick Osborne to Military Service Registration Board, 6 August 1935, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes (1RB2490).

33 List of weapons issued, B Company, 1st Battalion, Belfast Brigade, 12-31 December 1921, PRONI, HA/5/655 Seizure of cache of arms in Belfast and prosecution of James and Patrick Doherty and Edward Kane.

34 List of persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick; Occurrences in Belfast, 21 May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A File of reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922.

35 Northern Whig, 25 May 1922.

36 Belfast News-Letter, 27 May 1922.

37 Hugh Corvin interview with Military Service Registration Board ,17 July 1936, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes (1RB2490).

38 Patrick Osborne to Military Service Registration Board, 6 August 1935, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes (1RB2490).

39 District Inspector R.R. Heggart to Inspector General, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), 20 April 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

40 MA, MSPC, RO/403, 3rd Northern Division, No. 1 Brigade (Belfast), 1st Battalion.

41 Special “Six County” cases, n.d., MA, MSPC, SPG10A-1 Special investigation of Six County cases.

42 Captain Thomas McAteer, Adjutant, 17th Infantry Battalion, to Colonel F. McHenry, Adjutant-General’s Office, 3 May 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

43 List of persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

44 Sergeant Richard Ormond to Station Sergeant, Cullingtree Road Barracks, 26 August 1922, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

45 Particulars of Persons Arrested under Regulation 23 of Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act, 20 September 1922 & District Inspector D.C.B. Jennings to City Commissioner, RUC, 25 November 1922, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

46 Dr. P. O’Flaherty to MHA, 10 October 1922, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

47 Extract from Medical Officer’s Journal, HM Prison, Belfast, n.d., MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes.

48 Medical case sheet, 25 November 1922, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

49 Dr. P. O’Flaherty to MHA, 13 December 1922, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

50 Patrick Barnes to MHA, n.d. [October 1922], PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

51 Patrick Barnes to MHA, 13 January, 10 March & 25 March 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

52 Patrick Barnes to MHA, 12 April 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

53 Patrick Barnes to MHA, n.d., PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

54 Richard Mulcahy, Commander in Chief, to Mrs Barnes, 16 January 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

55 Captain Thomas McAteer, Adjutant, 17th Infantry Battalion to Colonel F. McHenry, Adjutant-General’s Office, 3 May 1923 & Minute sheet, 22 May 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

56 Patrick Barnes to MHA, 6 June 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

57 Patrick Barnes to MHA, 9 July 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

58 MHA to Inspector General, RUC, 1 August 1923 & Minute sheet, n.d., PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

59 District Inspector R.R. Heggart to Inspector General, RUC, 4 August 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

60 MHA to Governor, Larne Internment Camp, 11 September 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

61 Denise Kleinrichert, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2004), pp215-217.

62 Kleinrichert, Republican Internment, pp219-220.

63 Kleinrichert, Republican Internment, p226.

64 Governor, Larne Internment Camp to Secretary, MHA, 5 November 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

65 Secretary, MHA, to Inspector General, RUC, 7 November 1923 & Inspector General to City Commissioner, 7 November 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

66 City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 10 November 1923 & J.W.E. Poynting to Minister of Home Affairs, 14 November 1923, PRONI, HA/5/2181 Barnes, Patrick.

67 Pension ledger cards for 8937 Rifleman Barnes, Patrick supplied to author by RURM, 4 November 2025.

68 MA, MSPC, 24SP11321 Patrick Barnes.

69 Northern Whig, 6 September 1932.

70 Patrick Barnes application form, 5 May 1933, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes.

71 Ibid.

72 Patrick Barnes to Military Service Registration Board [sent from 23 Annadale Street], 23 October 1934, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes (1RB2490).

73 Pensions Branch, Department of Defence to Patrick Barnes, 14 January 1938, MA, MSPC, DP664 Patrick Barnes.

74 Unopened envelope addressed to Mr Patrick Barnes, 34 Albert Street, Belfast, marked in pencil “Gone away” and stamped “Received 21 Jan. 1938, Pensions Branch, Department of Defence”, MA, MSPC DP664 Patrick Barnes.

75 1939 Belfast Street Directory, https://www.lennonwylie.co.uk/acomplete1939_2.htm; Brian Barton, The Belfast Blitz – The City in the War Years (Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 2015), p177.

Leave a comment