Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

How many went south?

There are three main sources of information regarding Belfast men who travelled south to join the National, or Free State, Army during the Civil War:

- An Army Census was taken on the night of 12/13 November 1922; as local commanders had been allowed to recruit directly in their respective areas, the Provisional Government had no definitive overall picture of how many soldiers it had, all of whom needed uniforms, accommodation, weapons and pay; the census was intended to provide the missing information1

- Files released as part of the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) provide details of other men who were not included in the Census

- In 1923, a register was compiled, giving the personal details of northern men at one barracks in the Curragh in Kildare; crucially, this register also contains information regarding prior military service and where the men were subsequently sent or if they left the army2

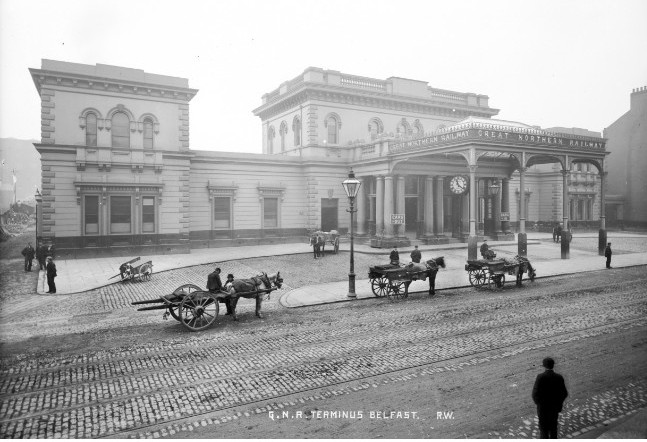

The Great Northern Railway station on Great Victoria Street was the point of departure for men going south to join the National Army (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Welsh Collection)

Using these sources, a total of 949 men and boys from Belfast can be identified who served in the National Army at some point during the Civil War.

Of those, only 234 can be pinpointed as having previously been members of the IRA or Fianna in Belfast: either they were included in the admittedly patchy and incomplete nominal rolls compiled in the 1930s as part of the Military Service Pensions process, or their MSPC files have been released.3

This means that 714 men, or 75% of the total, had no identifiable prior service with either of the male republican combatant organisations.

Prior to the start of the Civil War on 28 June 1922, 52 men from Belfast had enlisted: 23 former IRA/Fianna members and 29 non-members. Two events gave added impetus to the numbers travelling south.

The first was obviously the outbreak of the Civil War itself – this prompted a massive recruitment drive by the Provisional Government. In response to this, 96 non-IRA/Fianna members joined by the end of July, with another 85 joining over the following two months.

The second, which happened around the same time, was the final collapse of the IRA’s “northern offensive” which had been launched the previous May. With the introduction of internment on 23 May, many among the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions of the IRA began fleeing across the border to avoid capture – those of the 2nd Northern mainly going west to Donegal and those of the 3rd Northern mainly going south. On 2 August, a meeting was held in Portobello Barracks, Dublin, involving key officers from both divisions, as well as Michael Collins, Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy, Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy and other senior officers from the National Army. Those present agreed that the northern IRA would regroup south of the border with a view to resuming the offensive in the north:

“(1) That all IRA operations in the Six Counties would cease forthwith.

(2) That men who were unable to remain in the Six Counties would be handed over a barrack at the Curragh Camp, where they would be trained under their own officers to such tactics as would be applicable to the nature of fighting in the Six Counties.

(3) That they would not be asked to take any part in any activities outside the Six Counties.”4

By the end of August, there were 379 men from the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions in the Curragh. By 3 December, according to the register of the “Northern Volunteer Reserve” (NVR) in Keane Barracks in the Curragh, this number had grown to 524, of whom 84 were from Belfast.5

Belfast men arrived in the Curragh in a steady stream, evidenced by the dates on which they were attested to the NVR: 25 came in July, prior to the Portobello meeting; another 17 followed in August, 11 more in September and 29 during October.6

They remained in the Curragh, training for a new offensive which failed to materialise – the Provisional Government had decided in August to adopt a peace policy towards Northern Ireland, but this decision was not communicated to those in the Curragh until 20 October.7

Months of aimless training led to an element of disillusion, verging on mutiny, among those left in limbo in the Curragh. As early as 3 September, the IRA’s Assistant Chief of Staff, Ernie O’Malley told Liam Lynch that he had received intelligence that “some of the northern men there are disaffected and about 100 of them are disarmed and more or less semi-prisoners.” Some simply gave up and returned home to Belfast, among them James Cassidy from the Marrowbone, who “resigned with others in October 1922.”8

According to the former O/C of the Belfast Brigade, Roger McCorley, at the end of October, “We held a meeting with the Divisional O/Cs and Staffs and we decided that any man was free to go where he wanted, either to go home to the north or join the Free State Army … there was no pressure brought to bear on us whatsoever.”9

James Cassidy left the Curragh and went home to Belfast in October 1922 (photo courtesy of Jim McDermott)

Following this meeting, 44 of the NVR men in the Curragh – just over half – are noted in the register as having been “discharged;” presumably, they, like Cassidy, opted to go home to Belfast rather than join the National Army proper.10

Those who remained were then enrolled in the Volunteer Reserve (VR), a component part of the army; they were joined by other Belfast men, not necessarily all former IRA/Fianna members. Almost all were attested on a single day, 11 November, some having been discharged from the NVR that day and immediately re-attested to the VR; by the end of the day, there were 218 men from Belfast in this VR group.11

Where were the Belfast men?

The most striking thing about the Army Census taken in mid-November is that so many Belfast men were omitted: of the 218 in the register, 194 do not appear to have been recorded in the census; only 24 were, as members of “2nd & 3rd Northern Division”, the original detachment.

The largest single contingent of Belfast men who were in the census was in Louth, which accounted for 236 or over a quarter of the total, with all but eight of those being in Dundalk. This figure included 180 who had no known republican connections and 56 who had; all were counted in the census as being members of the 5th, not the 3rd, Northern Division.12

The most obvious explanation for why so many were in Dundalk was that it had the first railway station south of the border and so, was a more affordable destination in terms of train fare for unemployed men travelling from Belfast.

However, there is another possible explanation in relation to the former IRA/Fianna men. Apart from Ernie O’Malley, word of the disgruntlement among the Curragh contingent had also reached the unionist government of Northern Ireland – a civil servant noted, “Those who returned complain bitterly of their treatment, many of them tramped home from Dundalk, others travelled by train without tickets as the Free State did not pay their fare beyond Dundalk.”13

So it may be that some of these 56 men were moved from the Curragh by the military authorities in an effort to defuse the tensions that were growing there. It is particularly noticeable that while 33 of them had enlistment dates between 30 October and the date of the census, only two had joined prior to that and no date of attestation was recorded for the remaining 21.

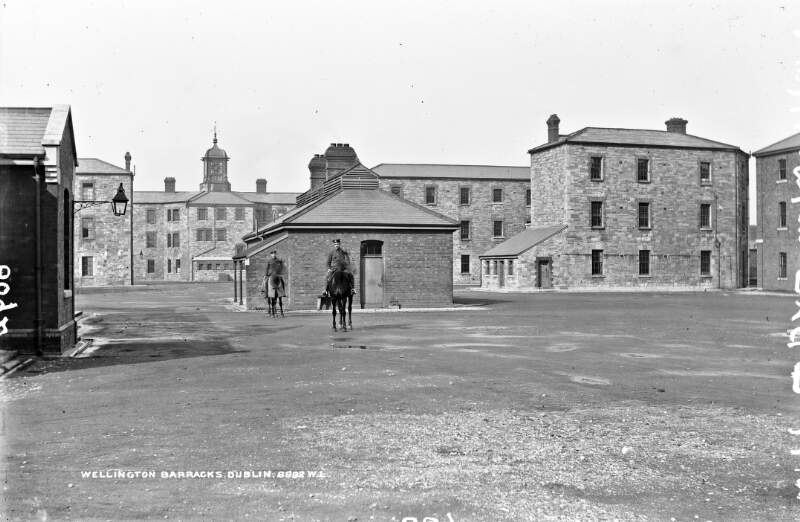

Wellington Barracks, Dublin (© National Library of Ireland, Lawrence Collection)

The census for Wellington Barracks in Dublin listed 103 Belfast men, of whom 90 were noted as being members of 3rd Northern Division. Every single one of those 90 men were attested in that barracks on the same day, 6 November, lending further weight to the argument that the original contingent in the Curragh was deliberately broken up. The fact that they were all recorded as being in the 3rd Northern Division suggests that there was massive confusion between different barracks over what to call the Belfast recruits: were they VR, 2nd & 3rd Northern Division or 3rd Northern Division?14

Only a minority among these men can be identified as having previously been in the Belfast IRA or Fianna, 25 out of the 90; as regards the other 65, one possible explanation is that they had originally been in the Curragh along with the others, but were omitted from the nominal rolls compiled in the 1930s and MSPC files for them have not yet been released.

When the census was taken, there were still 103 Belfast men in the Curragh, coincidentally the same number as in Wellington Barracks. This included the remnants of the 2nd & 3rd Northern Division composite unit and other men who were dispersed among specialist units, such as Engineers, Signals and Artillery. As with the men in Wellington Barracks, only a minority, 38 of them, have documented membership of the Belfast IRA or Fianna.15

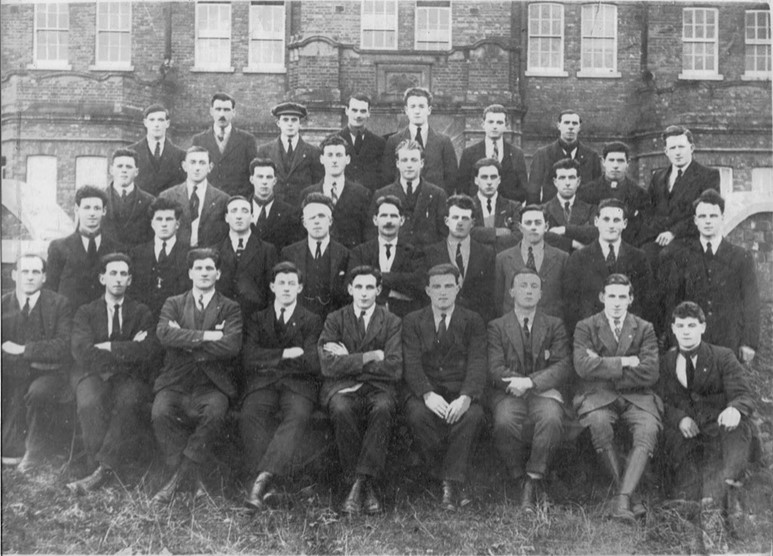

Members of the Antrim Brigade in the Curragh

Outside of these three main concentrations in Dundalk, Wellington Barracks and the Curragh, another significant group of Belfast men in the census was that numbering 37 in Kerry. Most of them were members of the Dublin Guards who had provided the main manpower for the National Army’s seaborne landings at Fenit and Tarbert at the start of August. It is noticeable that, with only one exception, none of those assigned to the Dublin Guards had prior service in the Belfast Brigade – these were mainly non-republicans who had travelled to Dublin to enlist when the Provisional Government launched its general recruitment drive at the start of the Civil War.16

There were other numerous groups of Belfast men in Monaghan (40), Meath (30), Cork (29), Cavan (22) and Donegal (19), with 36 more scattered in various other counties.17

Out of the total of 949 men, 44 joined the National Army after 13 November 1922.

Who were they?

In terms of age profile, 597 or just over two-thirds of the Belfast recruits were in their 20s, predominantly their early 20s. There were 191 teenagers, making up a fifth of the total, with eleven of those aged under 18. There were 84 men in their 30s and even thirteen in their 40s – the oldest was William Hallick from Carrick Hill, who was aged 49 and presumably enlisted out of economic necessity rather than a taste for adventure; in deference to his age, he was not sent into combat but instead was assigned to the army’s Salvage Corps.18

Among the youngest were brothers Gerald and Patrick Convery, aged 17 and 16 respectively – their family owned a pub on the Lower Ormeau Road. They were among several sets of brothers who enlisted. However, the strangest family unit was the McCrorys from Hawthorn Street off the Springfield Road: 40-year-old John, an IRA member, signed up at the end of August 1922 and nine weeks later, was joined at Gormanstown Camp by his 16-year-old son Gerald.

The Civil War was sometimes described as “the war between brothers.” The Corvins, who lived opposite the McCrorys in Hawthorn Street, illustrate the point. Peter joined the National Army on 1 October in the Curragh; later that month, his older brother Hugh was appointed O/C of the anti-Treaty 3rd Northern Division back home in Belfast.19

At the other extreme were the Crosbie brothers from Lowry Street in Ballymacarrett: Thomas aged 23, Richard aged 19, Patrick aged 18 and a fourth brother with the initial J all joined the National Army.

Those joining the National Army came from all the main concentrations of working-class Catholics in the city. Unsurprisingly, the Falls Road and the areas around it accounted for 47% of the total. A further 19% came from Carrick Hill, the New Lodge, Ardoyne and the Marrowbone combined. North Queen Street, York Street and Sailortown together contributed another 12%. Ballymacarrett made up 8% and the Market and Lower Ormeau 7% between them.

It was a trope of anti-Treaty propaganda that the National Army was largely composed of “a rabble of apolitical slum dwellers and former British soldiers, signed up for the pay.”20

For the register compiled in the Curragh, men were specifically asked about prior (non-IRA) military experience; applicants for wound or disability pensions or for dependents’ allowances under the Army Pensions Acts were asked about previous service in other armies, while the subject often arose in the course of applications for a Military Service Pension. Using the register and the MSPC as sources and ignoring the Army Census where the question was not asked, a sub-total of 371 men were asked if they were ex-servicemen.

Out of this sample, 106 or 29% were former members of the British Army or Royal Air Force (as well as two who had been in the Canadian Army); among them were an officer and 39 non-commissioned officers. Eighteen of the IRA members were ex-servicemen, or 15%; among the non-republicans, 88 were, or 35%. While the latter percentage is obviously much higher, it is not surprising, as it was the Hibernian-leaning majority of the city’s nationalist population which paid most heed to Joe Devlin’s encouragement to enlist in the British Army at the outset of the Great War.

However, the fact that less than a third of the total sample were ex-servicemen suggests that the republican propaganda claims were wide of the mark.

Casualties: combat and accidents

MSPC files released to date show that 28 Belfast men were killed, wounded or died of illness while in the National Army during the Civil War. Only a little more than half of these casualties occurred during combat. More strikingly, of the fifteen men killed, eight were killed by the IRA but six died at the hands of fellow-soldiers in the National Army; one died in an accident, the nature of which is unclear.

Kerry was the county where most recruits from Belfast were involved in combat.

The first Belfast fatality was 19-year-old William Carson, a corporal in the Dublin Guards. He was killed in action on 3 August during the National Army’s attack on Tralee which followed the landing at Fenit. Carson, from University Avenue off the Lower Ormeau, had previously been in the British Army but paid £38 to obtain a discharge and joined the National Army “in the hope of rapid promotion.” The family were described as “English people;” his father had been an organiser of ex-servicemen but by 1924 was an officer in the Special Constabulary.21

National Army troops landing at Fenit, 2 August 1922 (© Kerryman Archive)

Three more Belfast men were killed in Kerry in the following two months.

On 11 August, Sergeant William Purdy of the Dublin Guards, who had been in the Canadian Army during the Great War, was killed in Abbeyfeale, not by any IRA action but through the accidental discharge of a rifle – the army remained vague as to whether it was his own rifle or a comrade’s. His family lived in Camden Street near Queen’s University, although he had moved to Dublin after the family was forced to close their toy factory following the outbreak of the Pogrom.22

On 11 September, Michael Magee, from Vernon Street near Donegall Pass, was killed in an IRA ambush near Castleisland.23

Just over two weeks later, on 27 September, Daniel Hannan from Hardinge Street in the New Lodge was one of two Dublin Guards killed in an IRA ambush on their convoy near Farranfore. There was a controversial aspect to this incident which foreshadowed events in Kerry later in the Civil War. When announcing what had happened, the military authorities said that an IRA prisoner, Bertie Murphy, was being carried on one of the National Army lorries and that he subsequently died from wounds sustained in the ambush. However, according to Tom Doyle,

“… [the prisoner] was in one of the basement cells in the Great Southern hotel, Killarney, the Dublin Guard HQ, at the time of the ambush. When news of the attack reached Killarney, it was assumed that Murphy, a native of the area where the attack occurred, would know who was involved. Following a brutal interrogation during which he revealed no information, Bertie Murphy was shot dead.”24

In November 1922, some of the northern men were re-formed into a new unit; according to McCorley:

“I was sent south to Kerry with a unit which consisted of half Belfast men and half 2nd and 3rd Northern men. We went to Kenmare until March … Then I was fed up. I came back to the Curragh. I wanted to get out of the army or get out of Kerry. The unit then was formed into the 17th Battalion and sent to the workhouse in Tralee. Joe Murray, a Belfast man, was in charge of it then.”25

The Curragh register is particularly instructive on this subject. It shows that on 21 November, 193 Belfast members of the VR detachment – almost the entire unit – were sent to Kerry. Interestingly, 28 of the men discharged from the NVR left earlier that month – these were men who, unlike McCorley, were unwilling to go to Kerry in the first place.

It was while stationed in Kerry as a member of the 17th Battalion that Louis O’Hara, a former Belfast IRA volunteer from Thomas Street off York Street was wounded: his patrol was ambushed on 27 March 1923 between Sneem and Kenmare.26

Roger McCorley “wanted to get out of the army or get out of Kerry”

The final Belfast man to be killed in Kerry was Thomas Steenson from Brown Street off Millfield. In The Great War, he had served with the 5th Lancers and then the North Irish Horse, and although there is no record of him having any previous republican involvement, he was included in the Army Census as part of the 2nd & 3rd Northern Division in the Curragh. On 3 May 1923, he was killed in Kenmare, although the circumstances are unclear: his mother stated that he was killed accidentally by a bomb, although a newspaper report said that he died in a motor accident.27

Canice Quinn, from Cromac Street in the Market, was wounded in the course of an IRA ambush at Kilcummin in Kerry on 24 January 1923. He was shot in the leg and remained in a series of military hospitals until being discharged as medically unfit in August the following year.28

Five Belfast men were killed in combat in other parts of the country.

Two were killed in IRA attacks on posts while they were on sentry duty. Edward McAvoy from Kerrera Street in Ardoyne was shot dead on 9 August while guarding a post at Ferrycarrig in Wexford. Bernard Gray from Benares Street in Clonard was killed on 18 September at Coachford in Cork.29

Three died in IRA ambushes. On 21 November, Bernard Conaty from Cromac Street was driving a Crossley tender carrying troops near Carrickmacross in Monaghan when the IRA detonated a roadside mine and opened fire on the vehicle; Conaty died from his wounds the following day. Joseph Foster from Frere Street in the Lower Falls, who had been in the Belfast Brigade, was killed in an IRA ambush at Ninemilehouse in Tipperary on 18 January 1923. Joseph McCurley from Cullingtree Road, also in the Lower Falls, was killed when his patrol was ambushed in Cornmarket in Dublin on 23 February.30

Several other men from Belfast were killed by fellow-members of the National Army.

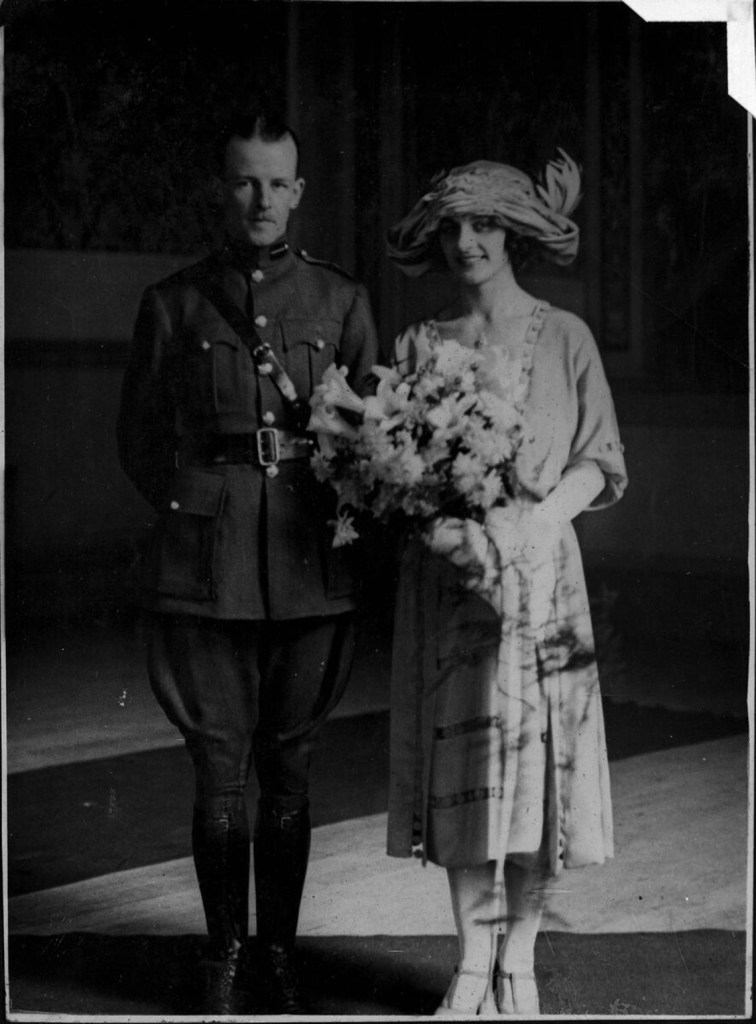

Charles Kearns, a former Belfast IRA member from Crocus Street off the Springfield Road and a sergeant in the Dublin Guards, was killed on 9 October in the Imperial Hotel in Cork. Newspaper reports avoided giving the details of the incident, either stating that he was “killed in action” at the hotel or was “killed in an ambush;” his MSPC file is equally circumspect about the precise facts of his death. However, Gerard Dooley has written that Kearns was one of many National Army soldiers in the hotel to celebrate the wedding of Emmet Dalton, the General Officer Commanding, Southern Command, and Alice Shannon:

The wedding of Emmet Dalton and Alice Shannon (© National Library of Ireland, Hogan Collection)

“On the evening of the wedding Kearns got into a row with a young intoxicated soldier named Andrew Rooney. The two men were separated by another army sergeant. However, crucially, no check was made to see if Rooney was armed. When Rooney encountered Kearns again, he shot him dead. Amidst the consternation, Rooney was arrested. He was found guilty of Kearns’ murder and was sentenced to death. This sentence was commuted by Richard Mulcahy to a term of five years in prison.”31

The circumstances in which Elmer Loftus from Divis Street was killed were farcical. On the night of 9 April 1923, he was acting NCO in charge of the guard at New Ross Barracks in Wexford. Intending to test the alertness of the sentries, he changed into civilian clothes and, taking his revolver with him, left the barracks with a view to sneaking up on them. As an ex-serviceman, he should have known better. One of the sentries spotted Loftus and ordered him to advance with his hands up. Loftus drew his revolver and attempted to grab the rifle from the sentry, who called for help. A second sentry arrived and saw an armed man in civilian clothes attacking his comrade but instead of tackling Loftus, he shot him in the side. Loftus died a few hours later, having praised the two sentries for their vigilance.32

Indiscipline and poor training were endemic in the National Army, for which several Belfast men paid a fatal price.

On 19 September 1922, Charles Flynn from Great Georges Street off North Queen Street was accidentally killed by a comrade in Limerick. Curiously, his mother’s application for a dependent’s allowance states that this happened while he was “confined to bed from a chill sustained by being immersed in a river in the course of an ambush;” there is nothing in his MSPC file to indicate that the army disputed this narrative or that they attempted to discover why a soldier was armed in a military hospital.33

National Army medics tend to a wounded soldier (© National library of Ireland, Hogan Collection)

James Montgomery, from Glenview Street in the Marrowbone, had been suspected of being involved in the killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn on 22 August 1920, although the authorities were unable to gather enough evidence to charge him. On the night of 23 April 1923 (the same night that Elmer Loftus was killed), intruders were spotted in the grounds of Moore Abbey near Monasterevin in Kildare. A search party of National Army troops was sent to investigate but during the search, Private William Jones – who had never been on a musketry course or even fired a rifle before – accidentally fired his, despite the patrol having been warned not to have any bullets in the breeches of their weapons. Montgomery was fatally wounded in the stomach.34

Almost a month later, on 17 May, Gerald Kane from Stephen Street near Carrick Hill was killed in Claremorris in Galway by a shot fired by accident by a comrade, John James Kelly.35

Apart from Canice Quinn, four other Belfast men sustained non-fatal wounds in combat. On 2 September 1922, John O’Connor from Exchange Street behind St Anne’s Cathedral was wounded in both legs during an IRA ambush at the City Club in Cork.36

Just two weeks later, on 17 September, a former Fianna member, Thomas Maguire from Fernwood Street off the Ormeau Road, was badly wounded in an IRA ambush near Boher in Tipperary. He was one of a party of 18 National Army soldiers marching to mass when they were attacked – a dum-dum bullet “tore away the muscles of his left arm.” Maguire was relatively lucky: three of his comrades were killed in the attack.37

Jimmy McDermott, a former IRA battalion commander in Belfast, spent the night of the census in the Mercy Hospital in Cork. He was the officer commanding a 50-strong detachment of the “Curragh Reserve,” consisting of men from various counties but including four from Belfast, which had been sent to Macroom in Cork. On 6 November, a National Army armoured car was attacked by the IRA outside the town; a rescue party led by McDermott was despatched and in the ensuing gun-battle, he sustained a gunshot wound that almost cost him his leg.38

Jimmy McDermott (L) almost lost his leg to a gunshot wound (photo courtesy of Jim McDermott)

On 28 December, Arthur McGivern from Servia Street in the Lower Falls was on patrol in Dawson Street in Dublin when the IRA threw a mine into a shop. This was the latest in a series of ironies to dog the veteran republican Denis McCullough. He had owned a musical instrument shop at home in Belfast but was forced to close it due to the impact of the Belfast boycott decreed by Dáil Éireann at the outset of the Pogrom; it was his shop, re-opened in Dublin, which was attacked. He had commanded the mobilisation of Irish Volunteers from Belfast at Coalisland during the Easter Rising, but that cut no ice with the IRA, who targeted his shop because of his support for the Treaty. The shop was destroyed, while McGivern was left with permanent partial deafness in both ears.39

Aftermath of bomb explosion in Dawson Street, Dublin, in which Arthur McGivern was wounded (Irish Times, 30 December 1922)

Returning to the theme of ill-discipline, a former commander of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion in Belfast, and subsequently of its Antrim Brigade, almost fell victim to a trigger-happy National Army sentry. On the night of St Patrick’s Day 1923, Tom Fitzpatrick, by then Officer Commanding Dublin District, was travelling on an armoured car from Collins Barracks on the quays to Keogh Barracks in Inchicore. Just after it passed Kingsbridge (now Heuston) railway station, a sentry called on the armoured car to halt. Due to the noise of the engine, the driver and the others on board did not hear the challenge, the armoured car kept going and so the sentry fired a shot, hitting Fitzpatrick in the lung. He survived.40

The previous month, Sergeant Bernard Monaghan from Lancaster Street off North Queen Street, an ex-serviceman who had been in the Royal Irish Regiment, had a similar escape: while in charge of the guard at Beggar’s Bush Barracks on 4 February, he had ordered the sentries being relieved to unload their rifles when a Private Laverty aimed his rifle and joked, “Wait until you see me shooting our sergeant” and then did just that, shooting him in the mouth.41

On 12 April at Inny Junction in Westmeath, James Macklin from Norton Street in Market, coincidentally also a Royal Irish Regiment ex-serviceman, was also wounded by another National Army soldier, except in his case it was his own company officer who accidentally fired his revolver. Macklin lost an eye as a result.42

John Fox from Cupar Street was discharged from the National Army as medically unfit, although the circumstances of his injury were so ludicrous that he might equally have been thrown out of the army for incompetence: “On 29 January 1923, while on guard duty, fell off a look-out post, about 10 feet high, at Beggars Bush Barracks.” He suffered a groin injury which led to a hernia.43

On 23 February, Margaret Campbell, living in Bow Street in the Lower Falls, received a telegram informing her that her son John had died, having been “accidentally injured by being run over at Dundalk Station by an engine.” Campbell had been serving in the Railway Protection Corps.44

The final Belfast casualty was not directly related to the Civil War but was medical in nature. While serving in the Mechanical Transport Corps, Arthur Smith from Tralee Street in Clonard got appendicitis on 21 May and died just over two weeks later.45

Executions and other killings

The very first Belfast man to be wounded was Daniel McGrath from Little York Street, who received a gunshot wound to the hand while stationed in a Dublin Guards post in Capel Street which was part of the cordon which had been put around the Four Courts. There was no mention of who had fired the shot, although he was wounded on 24 June 1922, four days prior to the start of the bombardment and assault which eventually led to the garrison’s surrender.46

Among that garrison was Joe McKelvey, one-time O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade and subsequently of the 3rd Northern Division. He was to have another confrontation with a National Army soldier from Belfast.

In his prison memoir, The Gates Flew Open, Peadar O’Donnell states that while in Mountjoy Prison, McKelvey read The Gadfly, a novel in which the key protagonist is sentenced to be shot by firing squad – however, the execution is botched and the man has to face two volleys in succession. According to O’Donnell, McKelvey was haunted by the image.47

Joe McKelvey (R) in Mountjoy Jail (© Kilmainham Gaol Museum)

On 8 December, in reprisal for the killing of a pro-Treaty TD, McKelvey was sentenced to be executed, along with three other senior IRA leaders also in captivity, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows and Dick Barrett.

The officer in charge of the firing party was Thomas Gunn, who had been an IRA officer in B Company, 1st Battalion in Belfast – so McKelvey was to be executed by a firing squad led by one of his own former subordinates. His execution was equally bungled, with McKelvey only wounded – he had to be given not one, but two coups de grace; according to Gunn’s granddaughter, her father:

“…heard from his father that he was present at the death of Joe McKelvey. My Dad remembers his father telling him that the first bullet shot him below the heart and that Joe asked for another and Grandad went up to deliver the shot but his finger froze on the trigger and that Hugo MacNeill delivered a second bullet and that Joe had asked for another.”48

Another former Belfast IRA officer was involved in the sequence of events that led to a different execution. My grandfather, Tom Glennon, had been Adjutant of the Belfast Battalion prior to the Pogrom, before a second battalion was set up in late 1920. Following his escape from an internment camp in the Curragh, he was appointed as Adjutant to the 1st Northern Division in Donegal in November 1921 and served there throughout the Civil War.

On 2 November 1922, eight IRA men led by Charlie Daly, the Kerry-born Vice O/C of the IRA’s 1st & 2nd Northern Division, were captured near Dunlewy. They were not court-martialled until two and a half months later, on 18 January 1923, when they were charged with possession of weapons and ammunition “without proper authority.” One of the three members of the court martial was my grandfather.49

Given that the eight men had been captured in possession of arms and ammunition, a guilty verdict was inevitable; this carried a potential death penalty, but no sentence was passed at the trial – instead, they remained in captivity.

Charlie Daly, one of the “Drumboe Martyrs” (photo courtesy of Donal Casey)

On 10 March, a National Army officer, Bernard Cannon, was killed in disputed circumstances in an attack on a barracks in Creeslough. Joe Sweeney, the National Army commander in Donegal, later said:

“We reported it and back came an order to execute four men, one of them Larkin. I sent a wireless message back for confirmation. The same message came back later. Then I sent a message direct to the A/G [Adjutant-General] Gearóid O’Sullivan. Larkin’s name came back again. He was from the Six Counties and I didn’t want to shoot a man from the Six Counties. I was very fond of Charlie Daly. He had been tried shortly after he was arrested but the sentence was confirmed.”50

On 14 March, Daly, along with Daniel Enright, Seán Larkin and Tim O’Sullivan were taken from their cells and executed by firing squad, afterwards becoming known as the “Drumboe Martyrs.”51

Former Belfast IRA officers in the National Army were also involved in two other killings of anti-Treaty IRA men during the Civil War.

On 11 December 1922, a month before the trial of the “Drumboe Martyrs,” two republican prisoners escaped from Drumboe Castle. A search party set out after Hugh Gallagher and a second man named Jordan and soon recaptured them. But Gallagher ended up being killed and Jordan wounded – my grandfather was again involved:

“Col-Comdt Glennon related how he went in pursuit, and after searching a wood met the sergeant with the prisoners. He gave directions for them to be put into the car. He was talking to the driver when the prisoners jumped off at the back. They were shouted at to halt but did not. Witness fired and hit the nearest man. Sergt Simms and another fired at the prisoners, who ran limping down the road. It was getting dark, and another shot was fired, and deceased dropped. A priest and doctor were got and everything possible done for the wounded.”52

“Shot while attempting to escape” is the oldest military lie in the book. However, although I am clearly open to accusations of family bias, I am inclined to believe my grandfather’s account, on the basis that the second prisoner was wounded, rather than being killed. If something more sinister was intended, he would have been finished off in the wood, instead of a doctor being brought to him.

The second incident involved McCorley and has been described as the last killing of the Civil War.

After the ceasefire order issued by Frank Aiken in April 1923, a small IRA flying column of thirteen men led by Neil “Plunkett” O’Boyle remained on the run in the west Wicklow mountains. On 15 May, they were cornered in a farmhouse near Blessington by National Army troops under McCorley’s command. He testified at the subsequent inquest into the death of O’Boyle:

“He pointed the rifle at me and fired. I fired simultaneously. I then took cover at the side of the door, continuing to fire into the house with a revolver … I called on all the occupants of the house to send the women out, saying I would give them two minutes more to get them out. Immediately after that a man rushed out of the front door and turned to the left in the direction in which I was standing. He jumped the small wall that I had crossed. I opened fire on him with my revolver, firing three shots. He fell.”53

One of the flying column captured at the scene later provided a very different account of the event. Tom Heavey said the National Army soldiers surrounding the house threatened to throw in hand grenades:

“This put Plunkett in a spot as he couldn’t let the women be injured. So he said, ‘Let me come out.’ Out he came with his hands up and walked slowly towards a stone stile, then at the right hand corner of the house. When he got there he spoke a few words with this Free State Officer named McCorley, a Belfast man perched on a stone ditch above him. Suddenly, McCorley raised his revolver and shot Plunkett in the eye, the bullet passing through his upraised hands. For good measure he shot him again through the head. He just shot him. I saw it all. It was cold blooded murder.”54

Heavey’s account was corroborated by other members of the flying column: “each man in turn was asked his name by the officer in charge, Roger McCorley. When Neil Boyle gave his name McCorley shot him dead on the spot.”55

In total, National Army firing squads executed 83 men during the Civil War. In addition to those official actions, the University College Cork Irish Civil War Fatalities Project has “identified at least 109 ‘unofficial’ executions, carried out by pro-Treaty personnel.”56

Neil “Plunkett” Boyle, killed by Roger McCorley in controversial circumstances

Before he left for Kerry, McCorley was also the subject of written complaints by republican prisoners in Mountjoy – they claimed that when they were being forced back to their cells, he had “shouted ‘smash his hands’ at a man holding on to the wires to resist removal and ‘throw him over the railings,’ before he fired at the prisoner with his revolver.”57

Unionist government reactions

The training of northern IRA men in the Curragh greatly alarmed the Northern Ireland government, who felt it pointed to an imminent general attack to be launched from the south.

An August 1922 report by their Military Advisor, Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood, warned: “There are indications that the re-organisation of various units of the Northern Divisions of the IRA is now in progress.” As evidence, he quoted from an intercepted letter addressed to a “Volunteer Cewsealey, 6th Northern Division [sic]” at the Curragh and also provided extracts from the interrogation of Patrick Kane from Vulcan Street in Ballymacarett, who had been arrested earlier that month: “I am a member of the Free State Army … I belong to the 3rd Northern Division … Yes the 3rd Northern Division is controlled by GHQ Dublin … We are under Michael Collins … We do not get any pay until we get our uniform.”58

When the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates, saw the report, he stressed: “The Free State Army in Ulster is what we have most to fear … they are awaiting their time to attack our government. Vigilance should not be relaxed.”59

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) continued to monitor the situation closely, gathering the names and addresses of men travelling south; they calculated that in eight months of 1922, some 1,685 recruits had left Northern Ireland to join the Free State Army, of whom 246 returned home having completed their training.60

Catholic nationalists were not the only ones taking the train south. There was initial consternation in official circles when the RUC at Great Victoria Street station reported that one day, over 30 Protestant men from the Shankill area and the Crumlin Road had left to enlist. However, having tried to ponder the potential implications, the authorities eventually adopted a sanguine view: if the Provisional Government went to the trouble and expense of training them, the men would make splendid Special Constables when they returned to Belfast.61

The unionist government took a much less relaxed view to northern recruits to the National Army returning home, particularly those who had been on their wanted list.

Joe McPeake from Little May Street in the Market was one of those who fled south of the border and joined the National Army, being stationed in Dundalk. By 12 March 1923, with the Pogrom over and the Civil War almost over, he must have judged it safe to visit his family back home and did so having got authorisation for two weeks’ leave from his superiors. Unfortunately for him, the northern authorities had long memories and two days after his arrival back in Belfast, the RUC arrested him.

They had been after him for some time. His arrest record reads: “Character – morally good, politically bad. Was one of the most active and dangerous characters in the city, involved in all murders and incendiary campaign. Was recommended for internment on 18-4-1922 but could not be found when his arrest was ordered in May 1922.”62

An internment order against McPeake was drawn up, directing that he be lodged on the Argenta but it was never actually signed. Initially held in Crumlin Road gaol, he wrote to the Ministry of Home Affairs, claiming that prior to joining the Free State Army, he had been a peaceful, law-abiding citizen:

“Previous to going about twelve months ago I was Acting Secretary to a pease [sic] committee for St Malachy’s district which waited on D.I. Armstrong at Chichester St (I may call it a [deputation] from the committee). The Rev. McKinnley of St Malachy’s or any of the gentlemen on that deputation can certify this.”63

The authorities weren’t fooled by this. Among the documents captured in a raid on the IRA’s Belfast Brigade HQ the previous July were some that identified McPeake as having been Adjutant of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion, along with receipts he had signed relating to the issuing and return of arms and ammunition.64

Panicked, McPeake then sent a telegram to the Assistant Adjutant-General of the National Army in Dublin, hoping for intervention from on high: “Was on leave from Dundalk. Nothing against me. No charge. Still detained. Had an official pass.” The northern authorities were aware that McPeake was a lieutenant in the National Army and were concerned that his arrest might prompt a strong reaction from Dublin, so on 28 March, Dawson Bates signed an order: “… do hereby prohibit the aforesaid JOSEPH McPEAKE from residing in or entering the following area, that is to say, any part of Northern Ireland outside the Rural District of Coleraine in the County of Londonderry.” Faced with a choice between internal exile to Coleraine or returning south to Dundalk, McPeake opted for the latter.65

Order banishing Joe McPeake to Coleraine (© PRONI, HA/5/2344. Used by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI).

In many ways, McPeake’s plight was emblematic of that of many who had made the journey south, particularly those who had once been in the IRA or Fianna. Faced with likely arrest if they moved back north, many had little option but to stay in the Free State or emigrate to farther shores.

Summary and conclusions

The men who left Belfast for the National Army from the middle of 1922 onwards mainly did so for one of two reasons, political or economic.

The initial wave of IRA and Fianna members who arrived in the Curragh did so for clearly political reasons – they wished to carry on the War of Independence that had begun in the north later than elsewhere, in the spring of 1920, but had also carried on in the north longer than elsewhere, where it had been brought to a close by the Truce. They were intent on launching fresh attacks on the unionist government of Northern Ireland.

Other IRA members who fled Belfast but never got as far as the Curragh – like McPeake or his battalion commander, Séamus Timoney, who both enlisted in Dundalk – also left for political reasons: their previous attempts to overthrow that government had failed and they were now hunted men.

By 1922, the postwar economic recession was beginning to bite in Belfast and unemployment was increasing. Work for Catholics had always been largely precarious in nature as they were heavily concentrated in casual occupations such as labouring, carting and dock work, but now, with thousands of returning soldiers competing for a shrinking pool of jobs, regular work was even harder to come by. The prospect of a guaranteed wage from the National Army had obvious attractions for jobless men. The fact that this entailed a risk of being shot at must have seemed eminently tolerable, given that they had already survived two years of deadly sectarian violence in the city.

The dominance of the economic motive over the political one can be seen from the numbers of men who joined the National Army – three quarters were non-republicans, driven by financial concerns, while only a quarter were politically-motivated members of the IRA and Fianna.

Some who joined may have had other reasons – the teenage Convery brothers were hardly troubled by economic necessity, for example, while others may have been seeking the same prospects for adventure that had led some of their older brothers to enlist in the British Army in 1914 – but such motives would not have been widespread.

While there were 31,469 National Army soldiers recorded in the Army Census, the army had increased in size to 48,176 by March 1923. The 949 Belfast men recruited to it therefore represented just 2.0% of its total manpower.66

The Irish Civil War Fatalities Project has identified a total of 638 members of the National Army who died during the conflict – mostly in combat, but also through accidents and illness. As a percentage of its 48,176 manpower, this represents a fatality rate of 1.3%. The Belfast men accounted for 2.7% of those fatalities, so a higher share than their share of the total manpower. Those seventeen deaths (eight killed by the IRA, six by National Army comrades, two accidents and one through illness) represent a fatality rate among the Belfast men of 1.8%, so also considerably higher than the overall National Army average. Being in the National Army was clearly more dangerous for Belfast men than for their fellow-recruits from many other counties.67

That is related to the fact that so many of the Belfast recruits were sent to Kerry. This was the county with the third-highest number of National Army fatalities, behind only Cork and Dublin. Between the 37 Belfast men in the Dublin Guards in Kerry by the time of the census and the 193 members of the VR sent there from the Curragh less than ten days later, a total of 240 men from the city were deployed to Kerry – a quarter of all Belfast recruits.68

Men from Belfast were centrally involved in some of the darkest aspects of the Civil War: the official and unofficial execution of prisoners and ill-treatment of captured republicans. The fact that it was specifically former IRA officers from Belfast who were involved is significant: the distinction suggests that Thomas Gunn, Tom Glennon and Roger McCorley had been so brutalised by their experiences of the Pogrom that by the time they joined the National Army, they were already psychologically damaged and more willing than others to break taboos.

The men who followed these officers south from Belfast to join the National Army, whether IRA/Fianna members or otherwise, were exposed to the consequences of many of that army’s flaws: poor training, indiscipline, drunkenness and downright stupidity. Whatever their motives for enlisting, it is highly unlikely that this was what they thought they were signing up for.

References

1 https://www.militaryarchives.ie/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922

2 Military Archives (MA), Historical Section Collection (HSC), Register, showing service number, rank, name, home address, date of attestation, age, unit to which posted, army qualifications, religion and date of discharge (hereafter “Register”), HS/A/0899.

3 MA, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Organisation and Membership Files, 3rd Northern Division, General Headquarters & 1 Brigade (Belfast), RO/401-406A.

4 UCD Archives (UCDA), Ernest Blythe Papers, File on pension claims by Northern IRA personnel, P24/554.

5 Ibid; MA, HSC, Register, HS/A/0899. Of the 84 Belfast men, only 32 can be shown to have been in the IRA or Fianna.

6 MA, HSC, Register, HS/A/0899.

7 Commander-in-Chief to O/C 3rd Northern Division, 20 October 1922, UCDA, Richard Mulcahy Papers, P7/B/287.

8 Assistant Chief of Staff to Chief of Staff, 3 September 1922, UCDA, Moss Twomey Papers, P69/40; James Cassidy to President, Executive Council, 9 June 1932, MA, MSPC, 1P682 James Cassidy.

9 Roger McCorley interview with Ernie O’Malley in Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmuid Ó Tuama (eds) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Kildare, Merrion Press, 2018), p103.

10 MA, HSC, Register, HS/A/0899. The register indicates that three other men were discharged but their MSPC files show otherwise; therefore, they are not included among the 44.

11 Ibid. In another sign that record-keeping may have been less than fastidious, 28 men remained in the register as members of the NVR, without being either discharged or re-attested.

12 https://www.militaryarchives.ie/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922

13 Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs to Cabinet Secretary, 5 February 1923, Reports of recruits leaving Northern Ireland to join Irish Free State Army, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/32/168.

14 https://www.militaryarchives.ie/online-collections/irish-army-census-collection-12-november-1922-13-november-1922

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 MA, MSPC, 3D181 William Hallick. No age was recorded for 64 men.

19 MA, MSPC, 24SP4648 Peter Corvin; MA, MSPC, MSP34REF24082 Hugh Corvin.

20 John Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin: The Fight for the Irish Capital 1922-1924 (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2017), p125.

21 Report of J.J. O’Callaghan, St Vincent de Paul Society, to Army Pensions Department, 23 June 1924, MA, MSPC, 2D242 William Carson.

22 Report of James McFaul, St Vincent de Paul Society, to Army Pensions Department, 11 July 1924, MA, MSPC, 2D40 William Purdy.

23 Adjutant, Southern Command, to Adjutant General, 23 September 1924, MA, MSPC, 2D444 Michael Magee.

24 MA, MSPC, 2D68 Daniel Hannon; Tom Doyle, The Civil War in Kerry (Cork, Mercier Press, 2008), p187.

25 Roger McCorley interview in Aiken et al, The Men Will Talk To Me, p104.

26 MA, MSPC, 3P112 Louis O’Hara.

27 Annie Steenson application form, 3 December 1923, MA, MSPC, 3D71 Thomas Steenson; Irish Independent, 7 May 1923.

28 MA, MSPC, 4P708 Canice Quinn.

29 MA, MSPC, 2D93 Edward McAvoy; MA, MSPC, 2D289 Bernard Gray.

30 MA, MSPC, 2D360 Bernard Conaty; MA, MSPC, 3D261 Joseph Foster; MA, MSPC, 3D42 Joseph McCurley.

31 MA, MSPC, 2D298 Charles Kearns; Irish Independent & Belfast News-Letter, 14 October 1922; Gerard Dooley, ‘Irish Civil War: 12 Munster killings that tell the story of the conflict’ in Irish Examiner, 3 January 2023.

32 Comdt James O’Hanrahan, O/C 20th Battalion, to Commanding Officer, No. 5 Brigade, 25 August 1924 & Sgt Major M. Doyle to Adjutant, 20th Battalion, n.d., MA, MSPC 3D281 Elmer Loftus.

33 Application form of Mary Anne Flynn, 17 March 1924, MA, MSPC 2D326 Charles Flynn.

34 Evidence of Lieutenant M.J. Doogan & Private William Jones at Court of Enquiry, 24 April 1923, MA, MSPC, 3D51 James Montgomery.

35 Verdict of coroner’s inquest, n.d., MA, MSPC, W3A Gerald Kane.

36 Application form of John O’Connor, 18 December 1923, MA, MSPC, 3P404 John O’Connor.

37 Captain P. Maher to Adjutant General, 24 October 1924, MA, MSPC, 4P498 Thomas Maguire.

38 Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001), pp271-272; MA, MSPC, James McDermott, 4P660.

39 Freeman’s Journal, 29 December 1922; MA, MSPC, 3P273 Arthur McGivern.

40 Adjutant, Curragh Military District, to Officer i/c Administration, Department of Defence, 4 December 1931, MA, MSPC, DP3490 Thomas Fitzpatrick.

41 Evidence of Sergeant Bernard Monaghan at Court of Enquiry, 7 September 1923, MA, MSPC, 4P467 Bernard Monaghan.

42 Medical report, 7 March 1924, MA, MSPC, 3P369 James Macklin.

43 Medical report, 8 May 1924, MA, MSPC, 3P315 John Fox.

44 General Russell, Railways Department, to Margaret Fox, 23 February 1923, MA, MSPC, 3D5 John Campbell.

45 MA, MSPC, 3D69 Arthur Smith.

46 Medical report, 11 November 1924, MA, MSPC, 3P1065 Daniel McGrath. McGrath had not been a member of the IRA while in Belfast but his case had an indirect connection to the Pogrom – his application for a wound pension was witnessed by Fr John Hassan, author of Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom.

47 Peadar O’Donnell, The Gates Flew Open, (Cork, Mercier Press, 2013), pp64-65; E.L. Voynich, The Gadfly (Teddington [Middlesex], Echo Library, 2007), pp197-199.

48 Email to author from Cathy Gunn (Thomas Gunn’s granddaughter), 14 March 2016. Hugo MacNeill’s father, Eoin, had been Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers prior to the Easter Rising.

49 Abstract of evidence for court martial, 18 January 1923, Ernie O’Malley papers, UCDA, P17a/191.

50 Joe Sweeney interview in Aiken et al, The Men Will Talk To Me, p35.

51 I have written more extensively about the “Drumboe Martyrs” here: https://www.theirishstory.com/2012/03/14/today-in-irish-history-the-execution-of-the-drumboe-martyrs-14th-march-1923/#.T8IXQrDL6WE

52 Irish Independent, 14 December 1922.

53 James Durney, ‘Death in the valley: the killing of Neil “Plunkett” O’Boyle’ in Journal of the West Wicklow Historical Society, No.6 (2011), pp8-15. I am very grateful to James for sharing a copy of his article. This killing has sometimes been incorrectly attributed to McCorley’s brother, Felix, also a former Belfast IRA man.

54 Ibid.

55 James McKee to Military Service Registration Board, 18 February 1933 & G. Boland to Military Service Registration Board, 4 March 1933, MA, MSPC, 2RBSD4 Neil Plunkett Boyle.

56 Andy Bielenberg & John Dorney, ‘Death and killing in the Irish Civil War’ https://www.ucc.ie/en/theirishrevolution/irish-civil-war-fatalities-project/research-findings/

57 Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin, p200.

58 Military Advisor to Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, 16 August 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/32/1/257.

59 Minister of Home Affairs minute, 19 August 1922, ibid.

60 File on reports of recruits leaving Northern Ireland to join Irish Free State Army, PRONI, HA/32/168.

61 Ibid.

62 McPeak [sic], Joseph, Little May St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2344. It is worth noting that this report states that internment lists were drawn up in mid-April, a full month before the killing of William Twadell and the internment provision of the Special Powers Act being activated.

63 Ibid.

64 Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

65 McPeak, Joseph, Little May St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2344. Nothing in McPeake’s file suggests any family connection to Coleraine. The 1911 Census shows a Joseph McPeake, then aged 9, whose mother was named Mary, living in Lissan, County Tyrone; the Army Census of November 1922 recorded his age as 20 and his mother’s name as Mary, with Little May Street now the family home. The release order signed by Dawson Bates would therefore appear to be a purely vindictive updating of Oliver Cromwell’s remark: “To hell or to Coleraine.”

66 Jack Kavanagh, ‘National Army Fatalities of the Irish Civil War’ https://www.ucc.ie/en/theirishrevolution/irish-civil-war-fatalities-project/research-findings/national-army-fatalities-1922-23/

67 Andy Bielenberg & John Dorney, ‘Death and killing in the Irish Civil War’ https://www.ucc.ie/en/theirishrevolution/irish-civil-war-fatalities-project/research-findings/

68 Ibid.

Leave a comment