Estimated reading time: 25 minutes.

Introduction

There were a number of groups reporting in detail on events during the Pogrom.

The City Commissioner of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), John Gelston, sent daily summaries of “Occurrences in Belfast” to his superior, the Divisional Commissioner, Charles Wickham. One of the most notable features about these reports is that the police were extremely diligent about recording not just the religion of the victims – RC for Roman Catholic, P for Protestant – but also the religious or political profile of the area in which an attack occurred and also the area from which it was made.

The main weakness of the “Occurrences” is that they focussed almost exclusively on incidents involving firearms, whether those were political/sectarian attacks or armed robberies; however, other forms of violence were not usually reported.

Belfast was well-served with newspapers. The three unionist titles – the Belfast News-Letter, Northern Whig and Belfast Telegraph – tended to repeat verbatim the police “Occurrences” reports, which obviously doubled up as press releases. In part, this may reflect constraints imposed by the realities of the conflict: most of the violence happened in Catholic or mixed areas, where reporters from those papers may not have been warmly received. The nationalist Irish News faced fewer such obstacles.

In the spring of 1922, as the violence escalated, a Belfast Catholic Protection Committee (BCPC) was established. Its patron was the Catholic Bishop of Down and Connor, Joseph MacRory, and its chairman was one of his most trusted parish priests, Fr Bernard Laverty of St Patrick’s in Donegall Street. However, this was not simply a clerical body, tapping into the network of Catholic priests in the city – the Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, David McGuinness, claimed that “we set up” the Committee: “The County Secretary of the Hibernians, Felix [sic – James] Kennedy was also on the Committee. Dr McSparran was by way of being an honorary member … the real work was performed by our Intelligence staff and all the information collated by the Compan[ies], Battalions and Brigade was tabulated here.”1

In order to highlight the plight of Belfast Catholics at this time, the BCPC began issuing weekly reports on events but soon escalated to daily ones. Sent in the first instance to Michael Collins, these reports form the core of many files maintained by the Provisional Government and later the North East Boundary Bureau. Like the RIC “Occurrences”, the BCPC reports were even-handed in listing the killing and wounding of Protestants as well as Catholics, but with a much more extensive range of sources than the police, they were able to provide additional detailed accounts of other attacks on Catholics beyond those that involved shootings.

Finally, before the BCPC was established, Collins had already despatched a special investigator to Belfast in early 1922 to provide him with information on what was happening: his fellow-Corkman and brother-in-law, Patrick O’Driscoll. Thus, the files of the Provisional Government contain material supplied by both the BCPC and by O’Driscoll.

April 1922 was deliberately picked for this analysis as the violence in Belfast actually diminished that month: 70 people were killed during March but “only” 34 in April. April 1922 also came immediately after the signing of the second Craig-Collins Pact on 30 March; that agreement, negotiated on a tripartite basis between London, Belfast and Dublin, had opened with a triumphant statement, “Peace is today declared.”

The reality two weeks later was very different.

14 April

Three men were killed on the Crumlin Road before most people in Belfast had even had their breakfast.

At 5:30am, Matthew Carmichael, a 45-year-old Protestant baker was passing the Mater Hospital on a cart with another man named Daniel McGrath when they were held up by three or four men and taken down nearby Bedeque Street. The Provisional Government report claimed that when they were asked their religion, McGrath produced a C Special identity card, but Carmichael hesitated and so was assumed to be a Catholic and then shot by Protestants; this version of events is pitifully dubious, as out of 62 people named Daniel McGrath on the whole island in the 1911 Census, only two were not Catholic. In any event, McGrath was spared and Carmichael was shot dead.2

Just 45 minutes later, most likely in retaliation for the killing of Carmichael, Daniel Beatty, a Catholic aged 26 from Ardoyne, had just passed Ewart’s Mill on the Crumlin Road when he was shot four times at the corner of Geoffrey Street, which the RIC noted was a “unionist area”. He died in hospital that evening.3

Also at 6:15am, another Protestant baker was shot dead, this time at the corner of the Crumlin Road and Tasmania Street – John Sloan was 50 years old and was killed while returning to his home in Harrison Street in the Shankill from working the night shift in Mercer’s Bakery in York Street.4

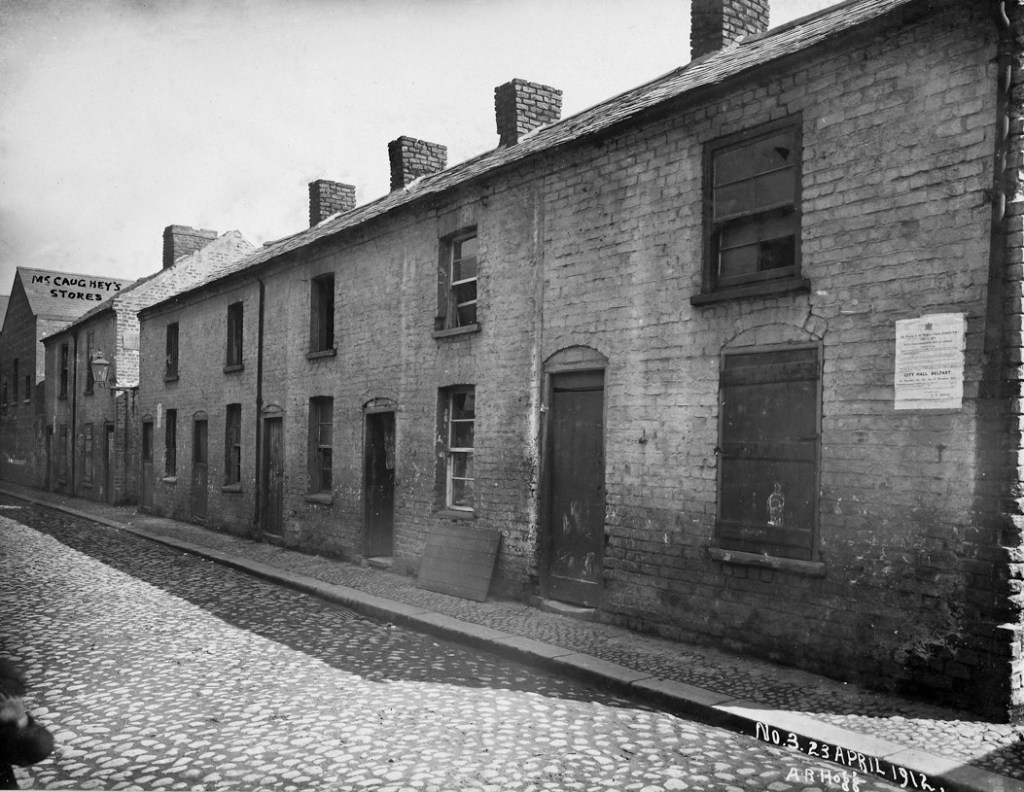

Corner of Crumlin Road and Tasmania Street, where John Sloan was killed on 14 April

Around the same time in west Belfast, “shots were exchanged between rival parties in Cupar Street area and in the fields adjoining Springfield Road. No casualties reported.”5

The rest of the day was quiet until the violence resumed in the evening.

At 8:10pm, a bomb was thrown into the grounds of St Matthew’s Catholic church on the Newtownards Road but no-one was injured and there was no damage done. An hour later, “two men entered the house of Edward Cooper, RC, window cleaner, 8 Albertbridge Road, and pushed his little daughter into a back room. They asked for Cooper who was out. They said they would shoot him.”6

Just after 9pm, “a young man came to the house of Phillip Grogan, RC, 21 years, 40 Valentine Street, and fired a revolver shot at him which struck him in the thigh.” This was stated by the police to be a “mixed area” near North Queen Street.7

At 9:40pm, three revolver shots were heard in Ardoyne, followed ten minutes later by four or five rifle shots fired from Flax Street. A report to the Provisional Government noted “Congregation fired at on leaving Holy Cross Catholic church” – this may have been the same incident. There were no casualties. A short time later, at 10:15pm, a police Lancia armoured car was fired at in Ardilea Street in the majority-Catholic Marrowbone, or ‘Bone, area; when the police returned fire, “extensive fire was opened and several bullets struck the car. No person injured.”8

About 10pm, some shots were fired from Argyle Street on the edge of the Shankill towards Kashmir Road in Clonard; again, nobody was hit.9

At 11:30pm, a number of men entered the cleaning shed of the Midland Railway station on the York Road and shot dead an engine-driver, Thomas Gillen, a 63-year-old Catholic. His killing prompted a resolution being passed by the trade union of which he was a member, “calling on the various railway companies and local authorities to provide adequate protection for members of the union while in discharge of their duty.”10

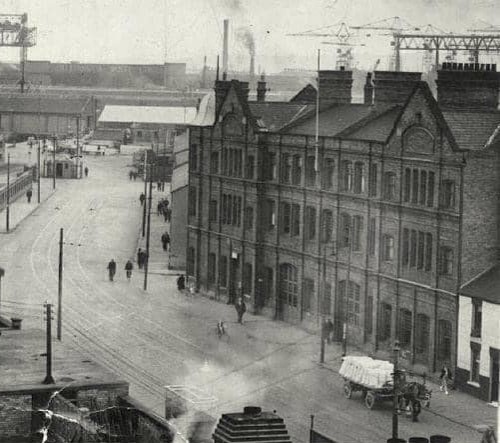

Midland Railway station, York Road, where train-driver Thomas Gillen was killed on 14 April (© Belfast Local History Magazine, Facebook)

15 April

This day was mainly notable for a string of armed robberies – the RIC reported no fewer than twelve such incidents that day. There is no way to know the identities or motives of the perpetrators – whether they were members of one of the combatant groups raising funds to buy weapons or food for men on the run, or simply criminals taking advantage of the fact that guns were plentiful in Belfast.

In contrast, in what was an unmistakably sectarian attack, the Catholic curate of St Matthew’s, Fr Burns, was fired at by a group of five men as he was going from the presbytery to the parochial hall, but he was not hit.11

Immigrants were not safe. The RIC said that at 8:45pm, two men entered the ice cream shop of David Borza on Duncairn Gardens and told him he had 48 hours to live; the Italian had made the mistake of opening a shop in what the police described as a “unionist area.”12

An hour later, Special Constable George Smartt was on plainclothes duty at the Shore Road tram depot on the north of the city when “he was held up by four young men who asked him his religion. He pushed them away. They then fired three shots at him but missed. He replied by firing two shots. The men then ran away. The Constable does not know if any of the men were wounded.”13

Shore Road tram depot, where Special Constable George Smartt was attacked on 15 April (© Belfast Local History Magazine, Facebook)

16 April

This was Easter Sunday and the city was quiet for almost the entire day.

However, at 7pm, five men tried to break in the front door of a pub in Ship Street in Sailortown owned by a Catholic man, James McAuley. He stuck his head out of an upstairs window and shouted for help – “One of the raiders produced a revolver and threatened to shoot him.” The attackers fled when police arrived on the scene.14

Five shots were fired in the ‘Bone area around 10:40pm, by whom was not stated, but no casualties were reported.15

17 April

After the Easter Sunday lull, violence resumed early on the bank holiday the next day. At 9:35am, St Matthew’s came under bomb attack again while mass was in progress, but like the attack three days earlier, no damage was done.16

The worst of the violence happened in north Belfast.

In the morning, the final of the Junior Shield football competition was played at the Solitude ground of Cliftonville. At 12:30pm, a crowd returning from the match began firing revolvers into the ‘Bone which drew shots in response. Two Lancias were despatched and patrolled the area for a couple of hours; firing continued until about 2:30pm, during which a Protestant woman named Sissie Wilson was wounded in the eye while cleaning the windows of her Oldpark Road home.17

At 3pm, two Specials on duty at the junction of Alliance Avenue and the Cliftonville Road were shot at from the direction of Ardoyne. They saw one man firing from behind a gate post and returned fire; a Lancia arrived and opened fire on some men running away, “but apparently without effect.”18

Meanwhile, shooting had resumed around the ‘Bone from 4:15pm. More Lancias were sent in and a local resident, Annie McAuley of Glenpark Street, was fatally wounded – her mother subsequently testified at the inquest into her death that while sitting in the kitchen at the back of the house, she had been hit by a burst of machinegun fire that came through the front window from one of the Lancias: “Here the girl’s mother produced the skirt her daughter had been wearing. It was completely riddled by bullets.”19

The police report made no mention of the fact that the fire brigade was called out twice that night to deal with houses which had been set on fire in Antigua Street in the ‘Bone. The first call came at 8:50pm and fire engines from the Shankill and Ardoyne Stations spent an hour bringing the blaze under control; the firemen had only been back in their stations for an hour when they were called back to the same street, where houses on the opposite side had been set on fire. Fifty Catholic families were left homeless.20

Houses in Antigua Street, burned out on 17 April

The Provisional Government report said that:

“… the loyalist mob from Ewart’s Row invaded Antigua Street and proceeded to loot it. After taking what was worth removing from the houses, the mob set fire to the houses. The refugees from these houses fled across the brick fields in the direction of Ardoyne district and when crossing these fields with whatever they could snatch from their houses they were fired on from a Lancia car stationed on the Oldpark Road at a point which commands these fields.”21

Among those listed as wounded during the intense fighting in the area was a man named James Cassidy. He was a member of the IRA and was wounded in the left eye: “We were quite close – it was an automatic that put me out so you can realise how close we were.”22

At 9pm, a clerical student, Arthur McKechnie, was wounded while walking in the grounds of the Ardoyne Passionist Monastery.23

Elsewhere, at 2:30pm, “while a funeral was passing along the Falls Road towards Milltown Cemetery three shots were fired from the unionist area of Conway Street. No person injured. The military were on duty at the time near the place but could not see who fired.”24

Pictured later in Free State Army uniform, IRA Volunteer James Cassidy lost an eye when wounded in the Marrowbone on 17 April (© Jim McDermott)

At 4:40pm, three shots were fired in Lisbon Street in Ballymacarrett; police were on duty nearby but could not establish where the shots were fired from; no-one was injured. Then, just after 6 o’clock, a Catholic named Hugh Dornan, aged 32, was fired at from Swift Street, a unionist street off the Woodstock Road, and wounded in the thigh.25

18 April

In a dawn raid in Disraeli Street in the Shankill, police arrested ten men who they found in possession of two Lee Enfield rifles and 87 rounds of ammunition, “together with some property looted from public houses.”26

Just after 7am in Ballymacarrett, shots were fired from Protestant Beechfield Street towards Catholic Thompson Street and a 67-year-old Catholic, James Greer, was wounded in the thigh. “Military were on the scene and with the assistance of the police carried out searches. Three men were arrested.”27

The Provisional Government noted that the presbytery of the Sacred Heart church in the Marrowbone was attacked with bombs and rifles. Sniping then continued in and around the ‘Bone for most of the day, in the course of which several people were wounded: a 14-year-old Protestant boy named John Hyland and a Protestant man named Daniel Lannigan, both of whom lived off the Crumlin Road, one Catholic man named John McMahon who lived in the ‘Bone itself and another, Thomas Murray, who lived in Ardoyne.28

The police report omitted the fatal shootings of James Fearon and James Smith, two other Catholic residents of the area. Fearon, aged 56, lived in Glenpark Street and was shot dead at about 8pm while returning home from work.29

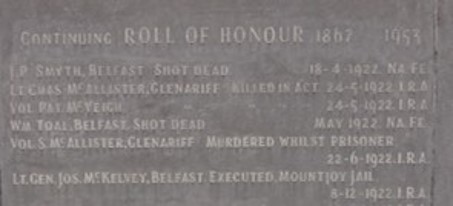

Smith was 14 years old and lived in Mayfair Street; evidence at his inquest indicated that he was shot in the head while standing at his front door, the shot being fired from the direction of Ballynure Street on the opposite side of the Oldpark Road. Although no Military Service Pensions file for him has yet been released, he was almost certainly a member of Na Fianna – the Roll of Honour on the republican County Antrim Memorial in Milltown Cemetery notes that J.P. Smyth of the Belfast Fianna was shot dead on 18 April 1922.30

Republican County Antrim Memorial, Milltown Cemetery; the first name inscribed on this section is that of J.P. Smyth, killed on 18 April

Also wounded in the Marrowbone during the day was Captain Pepworth, an Intelligence Officer with the Norfolk Regiment of the British Army. He was not the only casualty from that regiment: “At about 4:30pm, a military patrol of the Norfolk Regt shot a sniper dead in the Marrowbone area and got possession of his rifle. He was at the junction of Ewart’s Row and Antigua Street. His name is William Johnston, P, 24 years, Louisa Street. He was after shooting at and wounding Private Grant of the Norfolk Regt at the time.” Johnston was a B Special – at the inquest into his death, his widow provided a very different narrative, claiming the military had asked for volunteers to help locate snipers and that he had simply been hit in the general firing.31

Within hours of giving birth, a Catholic woman in the ‘Bone was evicted from her home by loyalists. The BCPC reported that,

“Mrs McKnight, 58 Glenview Street, mother of nine children, was confined at 6:30am and at 12 o’clock she was forced to leave by the mob before the baby was six hours old. Four weeks ago, a bomb was thrown into her bedroom by loyalists but fortunately did not explode. Mrs McKnight is the mother of nine children, seven of whom are still living.”32

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Oldpark Road, “Mrs McGlade was driven from her house 37 Ballymoney St by the Orange mob. A ‘loyalist’ family immediately went into possession of her house. Mrs McGlade is a widow with five children and was driven from her home in Ballymacarrett in the Pogrom of 1920.”33

More homes were burned in the ‘Bone, this time in Saunderson Street, and a spirit grocery was looted. Police arrested eighteen people for these attacks.34

Houses in Saunderson Street, burned out on 18 April (© UCD, Desmond Fitzgerald Collection, P80/PH/151)

In the west of the city,

“Between 6 and 7 o’clock … Specials were sent out on duty on the Broadway-Falls Road. These were armed and fired into the surrounding Catholic streets; when the military came on the scene the Specials told them the fire had come from Catholic quarters. Several houses were searched without results. This conduct was duplicated at Grosvenor Road.”35

The killing of Agnes McLarnon was absent from the police report for the day. A 30-year-old Catholic woman from Arran Street in Ballymacarrett, she was fatally wounded by “a crowd” who fired shots at her as she walked along the Crumlin Road.36

19 April

On this day, Ballymacarrett saw ferocious violence.

“Fire was opened by A Specials this morning at 6am from Woodstock Rd (loyalist) into Thompson St (RC), from Albertbridge Rd (loyalist) down Lisbon St.” In response to these attacks, shots were fired from Thompson Street towards the Woodstock Road at 6:30am – a 16-year-old Protestant boy, John Scott, was killed at the corner of George’s Street.37

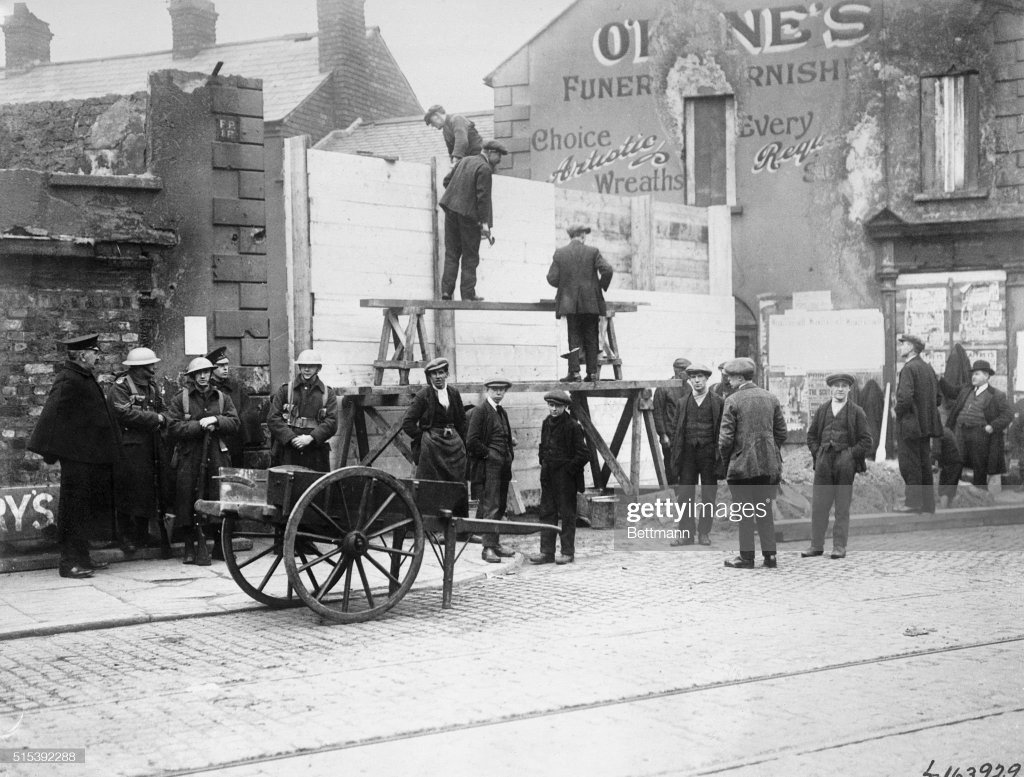

Peace lines erected on the Newtownards Road in March, like this one at the junction with Seaforde Street, may instead have channelled violence in April towards the Albertbridge Road part of Ballymacarrett

All afternoon, there was continual sniping around Thompson, Beechfield and Madrid Streets; two Catholics were wounded, Francis Barnwell in Moore Street and J. Fox in Thompson Street.. At 4:15pm, Special Constable Conn was in plain clothes passing along Madrid Street when he was fired on from the unionist side of the Albertbridge Road but escaped injury. Military and police could not locate the sniper.38

Around the same time, a number of men went to the home of Mrs Corr, a Catholic woman living in Mount Street off the Woodstock Road – when she opened the door, they fired at her but she got off lightly, only being wounded in the hand.39

A Catholic spirit grocer named Patrick McGoldrick was not so lucky. At 6pm, he was shot dead by two men in his shop at the corner of Madrid Street and Prim Street. Sniping continued until about 9pm, particularly back and forth across the Albertbridge Road between Short Strand and the Ravenhill Road and between Woodstock Street and the Woodstock Road. At 9:45pm, a bomb was thrown in unionist Fraser Street and Lilly Harvey was wounded by splinters.40

C1 Specials on the Albertbridge Road

The BCPC summarised the day: “A, B and C Specials running amok. Military have withdrawn leaving Catholic inhabitants to the mercy of the Orange ruffians and their comrades the Specials.”41

So intense was the violence in this area that the police report could not provide details of all the incidents, but had to settle for a summary of the casualties – another seven Catholics suffered gunshot wounds during the day. One of them was fatally wounded. He was mistakenly named as Francis Holden of Kilmood Street in the police report but his actual surname was Hobbs; he had been shot in Thompson Street as he went for a haircut and a shave – an eyewitness who had been accompanying him said there had been three men with rifles kneeling at the corner of Lisbon Street; another witness said the men who fired had been wearing armlets. In place of a uniform, C Specials were issued with Special Constabulary armlets.42

Two Catholic women, Rose Duggan and her neighbour Mary Ann Berry, were killed at teatime. Their deaths were noted in the police report for the day, although not the circumstances – these emerged at the subsequent inquest. Mrs Duggan’s husband said that his wife was preparing the tea for the children and Mary Ann Berry was standing at the door of the kitchen:

“As witness came downstairs he saw the muzzle of rifle protruding through a window at the back of Thompson Street. He told the other occupants of the house to watch out, and just then a shot was fired, and on going into the scullery he saw the two women lying on the floor bleeding profusely. He could not say who fired the shot, but he knew it came from a window in Thompson Street.”43

The same shot killed both women.

There were other attempted killings in the area, which were accompanied by house-burnings and evictions. Around the corner from Thompson Street,

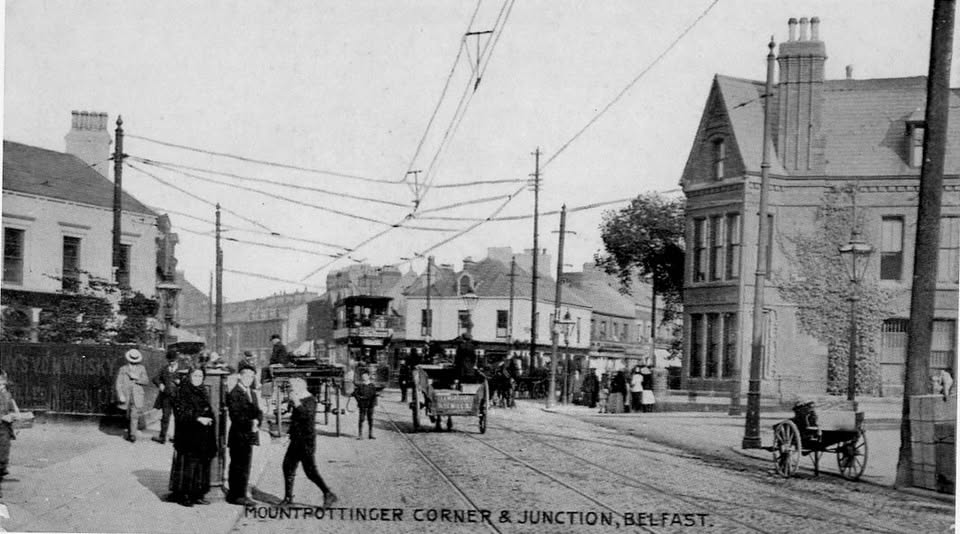

“John Raymond, 3 Altcar St, states that the loyalist mob armed with fifteen rifles and revolvers came to his house to burn it. Seven shots were fired through the window at him. Eight houses were burned in the street by the mob who were protected by the machine gun fire of a Lancia car stationed at Madrid St. Altcar St is opposite Mt Pottinger Barracks and the houses are only 100 yards distant from the barrack.”44

Not far away,

“A loyalist mob came to the door of Bernard O’Neill, 6 Moore St, Ravenhill Rd area. Mr O’Neill with wife and three children managed to escape into an entry at the rear of the house and concealed themselves there in a recess. The mob broke through the door and came into the entry shouting ‘Where the hell are they?’ This mob were armed with rifles and bayonets pointing to the fact that they were C Specials.”45

The rest of the city did not go unscathed that day. The BCPC gave a detailed account of how police stood around casually watching loyalist snipers in action in Sailortown:

“…three men spreadeagled across Whitla St towards Garmoyle St. During the time they were in operation there was one regular RIC pointman, two B Specials at Clarke’s public house, one A Special at Whitla St and Duncrue St, one C Special at fire brigade station and two B Specials at J. McAuleys corner of Ship St. None of these Specials made any attempt to interfere with the gunmen. A Lancia car of Specials drove through the area and made no search, though the crowds still gathered round the corners, but when they arrived at Pilot St corner they held up and searched a few dock labourers who were standing at the corner.”46

Whitla Street fire station, where Specials watched loyalist snipers in action on 19 April (© Northern Ireland Historical Photographic Society, Facebook)

Shortly after 4pm, two Catholic girls, Mary Frances Keenan aged 11 and Christina Toal aged 5, were wounded by a sniper while playing in Marine Street in the same area. The police noted that “five shots were fired from corner of Earl Lane and Marine Street, unionist area.” The elder of the two girls died a few hours later. According to the BCPC, “An A Special in uniform was standing with this man and an eyewitness saw the Special handing his rifle to the man who fired the shot.”47

20 April

At 5:30am, a regular RIC Constable and three A Specials were going along the Shankill Road when “four or five shots were fired from Brookmount Street, unionist area. The police searched around the place, but did not find anything.”48

Violence resumed in Ballymacarrett at daybreak. At about 7am, a Protestant man, James Johnston, was fatally wounded by a sniper while on his way to work in Anderson’s Felt Works on Short Strand. An hour and a half later, James Grieve, a Catholic, was shot and wounded in the stomach in his home in Hamilton Place off the Ravenhill Road.49

Junction of Mountpottinger Road, Albertbridge Road and Castlereagh Street (© Belfast Local History Magazine, Facebook)

The area was then quiet until the afternoon when, at 4pm, two C Specials, Special Constables William Galbraith and Albert Geyler, were wounded in Lisbon Street. The Provisional Government report for the day stated that they were “wounded in attack on Catholic quarter of East End.” Sniping then resumed around the Albertbridge Road – a 32-year-old Protestant named Raphael Rankin and a 20-year-old Catholic named Daniel Diamond were wounded; Diamond died half an hour after being admitted to hospital.50

At 6:10pm, a Protestant woman, Jennie Steenson, was wounded in crossfire between rival snipers in Beechfield Street. Twenty minutes later, Special Constable David Logue was shot in the arm, but his wound was self-inflicted – he accidentally discharged his revolver while in Mountpottinger RIC Barracks.51

At 6:45pm, a bomb was thrown at a Lancia at the junction of Thompson Street and Woodstock Street; it exploded under the car but caused no further damage, although “Sergt Curtis, who was in charge, is suffering from shell shock.” As no nationalists other than the IRA had access to bombs, this bomb can be assumed to have been thrown by the IRA.52

By the same token, the “man in civilian attire [who] came out in the middle of Thompson Street with a machine gun and, kneeling down, fired a round of shots towards Beechfield Street” can also be assumed to have been an IRA member. In this incident, a 14-year-old Protestant boy, James Greer – who, coincidentally, shared the same name as the Catholic man wounded two days earlier – was killed.53

In the course of the fighting, an IRA Volunteer, John Walker was killed. His mother later applied for a gratuity under the Army Pensions legislation; a report in the file states that “He was on outpost duty on the 20.4.’22 in the Short Strand district on which date the area was ‘shot up’ by C1 Specials. In replying to the attacking fire he was wounded in the throat, the bullet passing through the base of the skull killing him instantly.”54

Once again, the local RIC were so overwhelmed by the number of incidents in Ballymacarrett that they could do no more than catalogue the wounded – they listed two women and three other men; unusually, all were Protestants and the police noted that, “Some of the above casualties were believed to be wounded by military fire in reply to snipers.”55

Catholics living at the city end of the Ravenhill Road continued to be vulnerable in their homes. Mrs Farrelly of Empress Buildings left to do a message, leaving her seven children in the house. Shortly afterwards, five men knocked at the door – her 13-year-old son Vincent answered it and was asked his name and if the family were Catholics. He tried to close the door but one of the men blocked it with his foot and called to the others, “He is over 10 years,” implying that this was sufficiently old for him to be shot. The boy managed to get the door closed, so he and the other children ran out the back and sought shelter in a neighbour’s house until their mother returned.56

Mrs McAllister, a 70-year-old woman living at nearby 3 Hamilton Place, had to escape out the back when a loyalist mob broke open her front door; she returned to her home the next day, accompanied by military, “but all her belongings worth taking were gone.” At 11pm, the Lenaghan home at number 9 in the same street was also broken into and the family ordered to get out.57

Across the city, a 55-year old Protestant carter named Andrew McCartney was fatally wounded by a sniper at 2:15pm while leading a horse to a forge in Little York Street. “The shot was fired by a sniper posted at Garston Street and Little York Street, 300 yards away, unionist area. No shooting took place in this area up till this hour.”58

Little York Street, where Andrew McCartney was killed on 20 April (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Hogg Collection)

21 April

In the early morning, sniping resumed in Ballymacarrett, both around the Albertbridge Road and also towards the northern end of the district, on the Newtownards Road, Foundry Street and Clonallen Street. A B Special Sergeant, Charles Quinn, was wounded in the leg on the Ravenhill Road. “Military and police were on duty at the time and suppressed the outbreak and carried out searches.”59

At 3:45pm, a patrol of B Specials found the body of a Protestant man, Thomas Best, who had been shot in an entry between Ballycastle Street and Ballymena Street off the Oldpark Road. Beyond noting that this was a “unionist area,” the police had no additional information regarding the circumstances of the killing.60

There was another brief outbreak of sniping in Short Strand at 7:45pm, “to which military armoured car replied with machine gun fire. No casualties reported.” Firing resumed from 9:30pm to 11pm in Short Strand and Bridge End and once again, the military returned fire. A man named Graham who lived in the Salvation Army Hostel was wounded in the groin.61

The burnings and evictions continued: “The house of Ellen Smith, a Catholic widow with seven children, 9 Altcar St, was entered by an Orange mob who sprinkled petrol on the contents of the house and set it on fire. The house was completely gutted.”62

At 9:30 that night, in Delaware Street off the Ravenhill Road, “…three men came to the door. Miss Kerr asked who they were. The men said police she at once went back to the kitchen. Two shots were fired at her through the panel of the door none of which hit her.”63

The police report for the day stated briefly that in the New Lodge area at 9:20pm, British troops and Specials began shooting at each other when a military patrol at the corner of Lepper Street and Stratheden Street fired a shot: “B Special Constables in vicinity replied to the fire and a number of shots were fired by both sides. No casualties reported.”64

Specials and British military fired shots at each other in the New Lodge on 21 April

However, the BCPC provided a more extensive and distinctly different account of this incident:

“A resident in the New Lodge area states that the mob opened fire into Annadale St (mixed locality) and from Edlingham St (loyalist) Specials fired into New Lodge Rd. Military came from Victoria Barracks and fired upon the Specials and advanced up to corner of Edlingham St. He saw the Specials fraternise with the soldiers giving them cigarettes etc. After half an hour of this ‘peace making’ three of the soldiers got down on their stomach and opened fire into Catholic houses of New Lodge Rd and continued firing for almost an hour.”65

Shortly afterwards, and further north, “At 9:45pm, two Special Constables on duty crossing the vacant ground between Limestone Road and Mountcollyer Street were fired at. There were three shots fired in their direction, believed to be from behind a hoarding round Thompson’s Brickworks.”66

That night, shaken by the events of the previous seven days, the BCPC sent a despairing telegram to British cabinet ministers Winston Churchill and Austen Chamberlain. Even allowing for the element of hyperbole that was typical of public discourse in the 1920s, they were obviously petrified by what was happening:

“Belfast Catholics being gradually, but certainly, exterminated by murder, assault, and starvation; their homes burned; streets swept by snipers; life unbearable. Military forces inactive. Special police hostile. Northern Government either culpable or inefficient. Your Government saved the Armenians and the Bulgarians. Belfast Catholics getting worse treatment. Last two days here appalling.”67

Summary

Previous blog posts have looked at the nature of killings during the Pogrom and who was responsible. The most striking aspect of this examination of the minute detail of a single week in Belfast is how early the violence began each day. The nightly curfew was in place until 6am but the city frequently woke to the sound of gunfire: of the twenty people killed over the course of these seven days, five were killed before 7:30 in the morning, as both sides targeted people on their way to work or returning home from having finished a night shift.

This week saw almost the entire spectrum of violence: there were targeted sectarian killings of each side by the other; four women and an 11-year-old girl were killed, all Catholic, compared to fifteen men and boys. Neither youth nor old age offered any protection: a newborn baby was evicted with its mother, a 10-year-old boy was deemed old enough to shoot, while a 70-year-old woman was shot at in her home.

Much – though not all – of the violence was instigated by the Special Constabulary and loyalist paramilitaries. Not all of their violence was directed at Catholics: in both the Marrowbone and the New Lodge, Specials and the military ended up firing at each other as the Specials reacted with fury to being thwarted by British troops intent on preserving rather than shattering the peace. In the Marrowbone, this led to British soldiers killing a Special Constable who had wounded one of their comrades.

The IRA and its Fianna auxiliary attempted desperately to stem the tide of the attacks but to little avail: eleven Catholic civilians were killed, as opposed to six Protestants. Although the BCPC were clearly exaggerating when they talked of Catholics being “exterminated,” they were correct in highlighting the disproportionate extent to which Catholics were targeted. While it would be easy to speculate what the Catholic death-toll might have been if the IRA had not been there to provide some level of defence to nationalist areas, the critical point is that this defence was largely ineffective, owing to the huge disparity in numbers and armaments. However, contrary to what has been asserted by others, a member of each of those organisations was killed in action during this period, as well as one IRA Volunteer being severely wounded: providing defence carried deadly risks.

While house burnings and forced evictions had been a feature of the early stages of the Pogrom in late 1920 and again in July 1921, they increased in scale during the spring of 1922, eventually creating a flood of thousands of Catholic refugees fleeing south in the summer of that year. In this particular week, two whole streets were burned out in the Marrowbone as well as a significant portion of Altcar Street in Ballymacarrett. Also during this time, isolated and hence more exposed Catholics living on the “wrong” side of the Albertbridge Road, near the main arterial roads in the east of the city, became subjected to increasing intimidation, often accompanied by arson and attempted killings.

The worst of the violence in this week was concentrated in Ballymacarrett and the Marrowbone, although there were also killings on the Crumlin Road and in Sailortown, as well as one off York Street. That is not to say the rest of Belfast was quiet, as Specials shot up Broadway and the Grosvenor Road, while there were sporadic outbreaks elsewhere; however, what those areas experienced was a relatively low hum of violence compared to the shrieking intensity of that in the worst-affected areas.

Other areas would get their turn in the months that followed this week in April.

References

1 David McGuinness statement, Military Archives (MA), Bureau of Military History, WS417.

2 Occurrences in Belfast, 14 April 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A; Report for 14 April 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/8.

3 Occurrences in Belfast, 14 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

4 Ibid. The police report mistakenly gave James as Sloan’s first name.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid; Report for 14 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/6.

9 Occurrences in Belfast, 14 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

10 Ibid; Northern Whig, 21 April 1922.

11 Report for 15 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/6.

12 Occurrences in Belfast, 15 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

13 Ibid. The report gives his name as Artt, but there was nobody with that surname in the 1911 Census; however, there were two individuals named George Smartt, one living in Belfast and one in a rural area in Antrim.

14 Occurrences in Belfast, 16 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

15 Ibid.

16 Occurrences in Belfast, 17 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid; Belfast News-Letter, 2 June 1922.

20 Belfast News-Letter, 18 April 1922; Report for 18 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/6.

21 Report for 17 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/8.

22 Interview with Advisory Committee, 9 November 1937, MA, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), James Cassidy, MSP34REF10852.

23 Occurrences in Belfast, 17 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Occurrences in Belfast, 18 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

27 Ibid.

28 Report for 18 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/6; Occurrences in Belfast, 18 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

29 Northern Whig, 15 July 1922.

30 Belfast News-Letter, 2 June 1922.

31 Occurrences in Belfast, 18 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A; Northern Whig, 2 June 1922.

32 Report for 18 April 1922, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Art Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and Belfast Catholic Protection Committee (BCPC), Ms 8,457/12.

33 Ibid.

34 Occurrences in Belfast, 18 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

35 Report for 18 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/8.

36 Northern Whig, 21 June 1922.

37 Report for 19 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12; Occurrences in Belfast, 19 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

38 Occurrences in Belfast, 19 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

41 Report for 19 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

42 Occurrences in Belfast, 19 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A; Belfast News-Letter, 1 June 1922.

43 Belfast News-Letter, 1 June 1922.

44 Report for 19 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Occurrences in Belfast, 19 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A; Belfast News-Letter, 1 June 1922; Report for 19 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

48 Occurrences in Belfast, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid; Report for 20 April 1922, NAI, Atrocities in Northern Ireland, NEBB/1/1/6.

51 Occurrences in Belfast, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

52 Ibid.

53 Belfast News-Letter, 3 June 1922; Occurrences in Belfast, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

54 Director of Intelligence to Adjutant General, 16 May 1925, MA, MSPC, John Walker, 1D446.

55 Occurrences in Belfast, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

56 Report for 20 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

57 Ibid.

58 Occurrences in Belfast, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

59 Occurrences in Belfast, 21 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

62 Report for 21 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

63 Ibid.

64 Occurrences in Belfast, 21 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

65 Report for 21 April 1922, NLI, Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and BCPC, Ms 8,457/12.

66 Occurrences in Belfast, 21 April 1922, PRONI, Reports by RIC on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, HA/5/151A.

66 Belfast News-Letter, 22 April 1922.

Leave a comment