Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

After the 1921 General Election

Despite the election pact between the Nationalist Party and Sinn Féin, some of Joe Devlin’s supporters remained hostile to republicanism. In early May, a Mrs Smyth from Ashmore Street in west Belfast wrote to the authorities about “The following extremest,” a list of almost thirty names and addresses and in some cases, occupations: “There only one way to deal with these fellows. Come and arrest them and keep them in prison or the shooting will still continue. These men are out for trouble…I wish you could bring all these men to some intern camp [sic].” Ten of the names are either identical or close matches for those of IRA members which can be found in the files of the Military Service Pensions Collection.1

She complained, “Every Nationalist house in west Belfast the Sinn Feiners sit up all night painting the doors and windows of Nationalist[s in] Sinn Fein colours. We don’t want that.” But, referring to the killing of the two Duffin brothers in Clonard by a police “murder gang” in response to the IRA’s killing of two Auxiliaries in central Belfast, she congratulated the authorities: “However, at the same time I believe you got the right man … for the murder of the two Cadets.”2

Even a British Army officer noted, “Mrs Smyth’s letter is interesting in confirming the existence of ill feeling between the Nationalists and Sinn Feiners.”3

Sectarian violence in Belfast continued after the election – as Éamon Phoenix stated, “… the parliamentary activities of Devlin and his party were irrelevant to the bloody struggle which was taking place in Ireland between Sinn Fein and the British authorities.”4

On 12 June, in a retaliation for the IRA’s killing of Constable James Glover, who they had identified as being a member of the “murder gang,” two members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), Malachy Halfpenny and William Kerr, were abducted from their north Belfast homes by groups of Auxiliaries and members of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”). Halfpenny was shot dead outside Ardoyne Fire Station, while Kerr’s body was discovered off the Springfield Road the next morning.5

Malachy Halfpenny & William Kerr, Hibernians abducted and killed by a police “murder gang” in June 1921

In early July, Sinn Féin established beyond doubt that they were now the dominant voice in nationalism when a Truce was negotiated between the IRA and the British Army. Roger McCorley, the IRA’s Belfast Brigade commander, later claimed that the Hibernians had a hostile response to the Truce:

“An element of the Nationalists, under the control of the Hibernians, started to loot the unionist business premises in the Falls Road area … It was obvious that this was due to pique at the fact that our people were now accepted by the British as the official representatives of the Irish people. On several occasions during the day our men had to turn out and fire on this mob. They fired over their heads but later on in the evening I gave instructions that if the mob gave any further trouble they were to fire into it. We also sent our patrols with orders to arrest the ring-leaders of this group and bring them to Brigade headquarters. This was done and we ordered several of the ring-leaders to leave the city within twenty-four hours, otherwise they would be shot at sight. This action ended the Hibernian attempt to break the Truce.”6

However, there is evidence that a greater state of détente existed between some Hibernians and republicans than McCorley was later prepared to acknowledge. In August 1921, John Harkin, a Nationalist Party alderman on Belfast Corporation and also a member of the AOH’s Belfast County Board, wrote to the Director of Intelligence of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, Frank Crumney, offering to share an unlikely source of arms and ammunition:

“…it is possible to source 3 Webleys and 150 rounds of ammunition per week, at a cost of £5 per weapon and 50 rounds of ammunition. Additional ammunition can be secured in quantities to be arranged … I bargained but of course have to be careful as the stuff is coming from the Specials’ Depot at Newtownards.”7

This also demonstrates that, a year after the outbreak of the Pogrom, the Hibernians were still actively engaged in procuring weapons.

At the end of that month, rioting erupted around North Queen Street and York Street, with fourteen people killed. As a result, on 9 September, police and military officers invited political representatives from both sides to a meeting in Henry Street Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Barracks, with a view to arranging a local ceasefire. Eoin O’Duffy, the IRA’s Truce Liaison Officer for Ulster, and thus its overall commander in the province, does not appear to have been at the meeting but Harkin, as the alderman for the area, was – indications that the IRA did not have a monopoly on the use of arms by nationalists and that the RIC viewed Harkin as a useful conduit through which to deal with other armed nationalists.

Henry Street RIC Barracks, where talks were held to arrange a local truce in the North Queen Street area

In the event, the meeting broke up in acrimony, with Harkin telling the press: “The Catholics who attended Friday’s conference demonstrated the fact that if the Orange gunmen were kept in subjection then there need be no fear of disturbances; but a prominent Orange leader of the crowd stated that ‘he could not be responsible for imported gunmen’ and the conference thus terminated.”8

In late September, Harkin was a member of a delegation from Belfast which travelled to Dublin to meet Éamonn de Valera and the Dáil cabinet. Claiming to represent 100,000 citizens of Belfast, the group comprised an interesting cross-section of anti-partitionist councillors. Harkin was accompanied by his Nationalist Party colleague on Belfast Corporation, James McKiernan of the Cromac ward; James Baird, a Belfast Labour councillor, one of the “rotten Prods” driven from their jobs in the shipyards in July 1920 and prominent in the Expelled Workers Relief Fund; and three Sinn Féin councillors – Harkin’s fellow-councillor in Victoria, Joseph Cosgrove, as well as Dermot Barnes and Denis McCullough. The group presented a lengthy declaration which began: “We appeal to An Dail to refuse to recognise or consider any scheme of Government which would partition Belfast and the Six Counties of the North-East from the Government self-determined by the will of the big majority of the Irish people.”9

The makeup of this delegation gives credence to A.C. Hepburn’s assertion that “the Devlinite influence, at least in so far as hostility to Sinn Féin was concerned, was predominantly a Falls phenomenon.” The hostility on the IRA side was certainly mutual, with Tom McNally later telling Ernie O’Malley, “The Hibernians were of no use. Indeed, they were a menace through their weakness.”10

But in November 1921, Sinn Féin’s Seán MacEntee, defeated by Devlin in the Belfast West election earlier that year, wrote to de Valera to convey information that he had received from Harkin regarding a new initiative of the AOH’s National Secretary to overcome this supposed “uselessness”:

“Mr J.D. Nugent, about 3 weeks ago, made a tour of those N.E. Ulster Districts, including Belfast, where Hibernianism has a hold, in order to organise a new armed force among the Hibernians to be known as the Hibernian Knights. The ostensible purpose of this organisation, which is to be armed, and which is being formed on a strictly sectarian basis, is to defend the Catholics against Orange terrorism but my informant states that Mr Nugent, in his organising speeches spoke also of the aggressive attitude taken up by Sinn Fein towards Hibernians in certain districts.”11

The AOH planned to establish an armed wing, to be known as the Hibernian Knights

In the autumn of 1921, as Sinn Féin began the negotiations with the British government that would lead to the Treaty, Devlin was sidelined. De Valera felt that “’The majority party [Sinn Féin] is strong enough of itself to give the necessary lead. The Nationalist [Party] minority can support the policy and leadership of the majority in all matters that are of common interest.’”12

The AOH’s governing Board of Erin (BOE) did not have its usual quarterly meeting in September 1921, as it waited to see what the Treaty negotiations would produce. However, when it met on 6 December 1921, its secretary, Nugent, observed that “the hostility of the Republican Party against our Organisation has been even more marked during the last few months than ever previously.” He highlighted a series of arson attacks on, and thefts from, Hibernian halls – although it was notable that all of these incidents had occurred in border counties and none in Belfast; it may be that, for all the vituperation expressed by McCorley and McNally several decades later, the shared experience of Hibernians and republicans in the sectarian maelstrom of Belfast enforced a level of pragmatic co-operation like that shown by Harkin.13

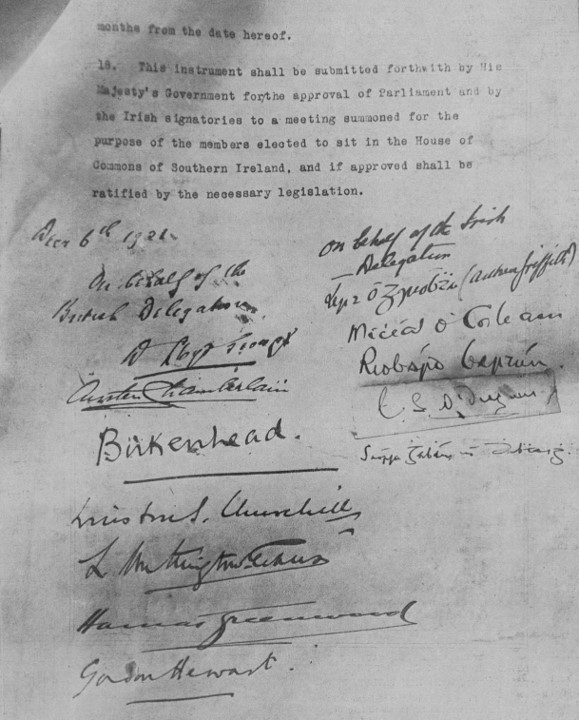

After the Treaty

That meeting of the BOE took place on the day that the terms of the Treaty were announced. Naturally, the AOH would be expected to have a view about such a seismic development but as Devlin was not present, they could not come to an agreed position without his input, so they decided to postpone the discussion until the following day:

“A general discussion arose as to whether it would be desirable to make any public pronouncement regarding the terms embodied in the Treaty recently signed, and as there was a difference of opinion as to the wisdom of such a course, action was deferred until the following day when the national president [Devlin] hoped to be able to attend.”14

The AOH sat on the fence regarding the Treaty

The postponed discussion succeeded only in devising a more elaborate fudge, with the AOH opting to sit firmly on the fence for at least several months:

“After a lengthy discussion on the question of a public pronouncement it was eventually agreed that no public statement should be issued for the present, but that a conference of all county officers be convened for some day towards the end of January with the view of discussing the future policy of the order, and if possible arriving at some definite scheme for submission to the next Convention.”15

At Westminster, Devlin continued to rail ineffectively against the impact of the Pogrom, telling Parliament on 16 February 1922:

“For over 18 months the people I represent in this House have been treated as outlaws … about 5,000 of them are walking about the streets without work to do, and have been walking about for nearly 18 months with their families dependent upon them. They have been left there with all these wrongs rankling in them, with this canker of wrong eating at their very hearts, and never has there been an attempt to conciliate them or to treat them well.”16

Later that month, Harkin made an appeal for nationalist co-operation across party political lines to the Freeman’s Journal:

“‘The present intensified condition of affairs in Belfast has been carefully and elaborately organised by the pogromists in their attempts to compel the Catholic minority into recognition of the Six County parliament by an appeal to that administration for protection’…Special Constabulary, the Alderman explained, had Belfast in their grip and the Catholics had every reason to realise their presence. So long as this force, he emphasised, was in existence, the lives of Catholics and their property would be in jeopardy … To obtain united action he suggested the holding of a conference of leading and representative Catholic citizens for the purpose of providing ground upon which the Sinn Fein and Hibernian organisations could act.”17

However, some on the republican side were firmly against such co-operation. If Devlin had been sidelined during the Treaty negotiations, he was even more firmly out of the picture in the spring of 1922, as Michael Collins came to be seen as the main champion of northern nationalists. Some wanted Devlin’s exclusion to be absolute: on 3 March, the O/C of the IRA’s 4th Northern Division, Frank Aiken, advised Collins, “in your future dealings with Ulster you should not recognise Joe Devlin or his clique … There can be no vigorous or harmonious policy on our part inside Ulster if his people occupy any position in our circle.”18

Frank Aiken urged Michael Collins to exclude Devlin and his followers

Devlinites and the Craig-Collins Pact

But unknown to Aiken, Collins had a variety of channels of communication going north, not all of which depended on Sinn Féin or the IRA and some of which involved Devlin’s followers.

In late February 1922, a Provisional Government statement said:

“On Tuesday (22nd inst) a Catholic merchant in Belfast was approached by a prominent police officer and informed that a large percentage of the RIC would offer themselves for Service under the Six-County Administration provided they had support from prominent Catholics and that the government are prepared to enrol a certain number of Catholics (preferably ex-soldiers or AOH who are not IRA men or members of the SF organisation). These Catholics are to be formed into a special police force, for duty in Catholic districts.”19

Nugent was quick to distance the AOH from this development:

“Permit me to say (1) that no officer, and, so far as I can ascertain, no member of the Ancient Order was approached by any person with the suggestion that Hibernians should join the northern, or any police force, and (2) that no communication on the subject, official or otherwise, has been received by any division of the organisation in Belfast or elsewhere … The Catholic merchant did not consult or communicate with any member of the AOH on the subject, and our organisation had absolutely nothing, directly or indirectly, to do with the matter.”20

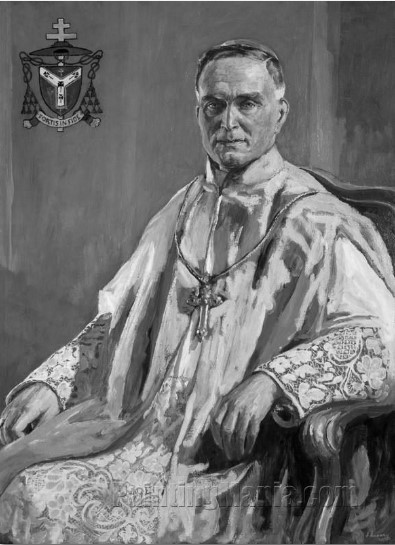

Nugent claimed that the “Belfast Catholic merchant” had relayed the police proposal to the Bishop of Down & Connor, Joseph MacRory, who then advised him to communicate with the Provisional Government.21

Although not named in any of the public statements, the “merchant” in question could have been either of two men who worked closely together: Raymond Burke, who had inherited his father’s extensive shipping company based in Corporation Street and who also owned a haulage company in Frederick Street, and Hugh Dougal, owner of another haulage firm.

The involvement of these two prominent Devlin supporters illustrates the extent to which the MP’s once-cohesive political machine was fracturing under the impact of its new-found irrelevance. While Harkin sought co-operation with Sinn Féin against the unionist regime, Burke and Dougal sought accommodation with that regime – recognition of it in return for protection of the minority.

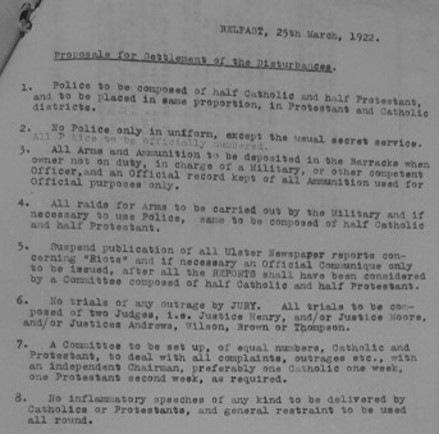

On 25 March, they met James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, to present a plan for restoring peace in Belfast:

- That police in Belfast should be composed of equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants and used in those proportions in both Catholic and Protestant areas

- All police except “the usual secret service” (i.e. detectives) to wear uniforms with official numbers

- All police arms and ammunition to be stored in barracks, under the control of either a military or senior police officer, when not in use by a policeman on duty

- All arms raids in Belfast to be carried out by the military; if police had to be used, then with equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants

- Replacement of newspaper reports concerning “riots” with official communiques

- Jury trials for “outrages” to be replaced by trials composed of two judges

- A committee of equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants “to deal with all complaints, outrages, etc;” chairmanship of the committee to be rotated on a weekly basis between Catholic and Protestant nominees

- “No inflammatory speeches of any kind to be delivered by Catholics or Protestants and general restraint to be used all round.”22

The peace plan proposed by Burke and Dougal (© PRONI, Disturbances in Belfast, CAB/6/37; image reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records

Three further points were added by Burke and Dougal the following day, but confusingly, the composite of all eleven points was back-dated to 25 March:

- “Disband Specials and organize a proper police force as described hereinbefore, and the Catholics will guarantee peace in their own districts.”

- “A committee of three to be set up, with Father Convery, or other clergyman which may be appointed, to recommend recruits for the regular police force, which recommendation to be final.”

- A proposal that “all men are allowed to return to their employment, without religious distinction of any kind whatsoever. No interference in any district with anyone on account of their religion.”23

The Burke-Dougal proposals formed the core of the second Craig-Collins Pact, signed in London five days later after negotiations overseen by the British Colonial Secretary, Winson Churchill. A heavily-annotated version of their plan is in the files of the Provisional Government in Dublin – the “Catholic merchant” anonymity they had been given in February was maintained and the Dublin version is titled “Proposals for settlement of disturbances made by certain Roman Catholic leaders in Belfast.” This terminology suggests that the Dublin version is a document which Craig shared with Collins during the discussions in London.24

The second Craig-Collins Pact aimed to reform policing in Belfast

In the final agreement, some of the Burke-Dougal proposals were amended:

- The stipulation regarding equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants in the Belfast police would now apply only to Specials operating in mixed areas; however, apart from “special arrangements” being made for Catholics or Protestants living in other districts, all other Specials were to be withdrawn to their homes and their arms handed in

- The Catholic advisory committee mentioned in point 10 of the original version was now to assist in the recruitment of Catholic Specials, rather than regular Catholic policemen

- Arms searches were to be carried out by police of equally-mixed religions, with the military only assisting if required

- Instead of the reinstatement of expelled workers, relief works which would offer them alternative employment were to be funded by the British government25

However, the other proposals were incorporated more or less unchanged. To those were added clauses relating to a cessation of IRA activity in the north, “the return to their homes of persons who have been expelled,” the release of political prisoners, and a rather woolly commitment to hold future discussions to explore “whether means can be devised to secure the unity of Ireland” and if none could, whether the border could be determined without recourse to the Boundary Commission specified in the Treaty.26

Devlin himself was not at the meetings in London but constitutional nationalists were now more central to events than at any time since the 1921 election.

While the terms of the Pact began to be implemented, Dougal had not given up on the suggestion originally made in February: “Dougal hoped to enlist members of the Hibernians in the proposed mixed police force and played a leading role in trying to quell the disturbances in the nationalist Markets district where the USC had been involved in a number of incidents.” Following meetings in April with the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates, and the local RIC District Inspector, “arrangements were made for the enlistment of local men to patrol the district … [but] they were in turn attacked by Sinn Fein as ‘accommodating Catholics.’”27

Having heard from a deputation regarding IRA and Sinn Féin opposition to the RIC oath of allegiance which Catholic recruits to the Specials would be required to swear, Collins nominated his representatives to the Police Advisory Committee on 25 April. These were: Bishop MacRory and two Belfast parish priests, two leading Sinn Féin figures, Dr Henry Russell MacNabb and Frank McArdle, Alderman Harkin and several Devlinite businessmen; the intended foxes in the henhouse were Crumney, the IRA’s divisional Director of Intelligence, and Daniel Dempsey, a member of the intelligence staff of its Belfast Brigade.28

Bishop Joseph MacRory, nominated by Collins to sit on the Police Advisory Committee

The policing committee made little headway. At its first meeting, Crumney unsurprisingly spent much of the time trying to establish the exact strength of the Specials. On the day for which the second meeting was scheduled, Crumney and Dempsey were arrested and subsequently interned – fearing the same fate, MacNabb and McArdle promptly went on the run; at the meeting itself, RIC Divisional Commissioner Charles Wickham and City Commissioner John Gelston were adamant that Belfast Catholics could not be recruited as A Specials to serve in Belfast as RIC regulations forbade whole-time policemen serving in their home counties. By the time of the third meeting on 7 June, Harkin was no longer attending and Fr Murray, parish priest of St Mary’s, furiously pointed out that he could hardly encourage Catholics to join the Specials when Specials had shot up his presbytery just a week earlier.29

The Pact finally collapsed amid a welter of recriminations: Craig rejected Collins’ demands for a public inquiry into the Arnon Street killings; he also refused to countenance the release of 170 IRA prisoners on a list submitted by Collins. For his part, far from instructing the IRA to cease activity in the north, Collins was actively engaged in providing arms to it so that it could increase the scale of its activities. Craig also pointed to Collins’ failure to prevent the anti-Treaty IRA in the south from putting in place a renewed Belfast boycott aimed at goods and services of northern origin.30

However, the most immediate cause of the Pact’s failure was the response of its most implacable opponents – the Specials and loyalist paramilitaries. In the first three months of 1922, 78 Catholics were killed in Belfast; far from the Pact ushering in a period of peace, in the three months after its signing, 86 more Catholics were killed.

Attempts to encourage Belfast Catholics to join the Specials collapsed (© National Museum of Northern Ireland)

Bringing Devlin back into the fold

With the disintegration of the Craig-Collins Pact, Burke, supported by Devlin, embarked on a new initiative. On 2 June, he met Churchill and presented:

“… proposals that the police force in Belfast should be 50/50 Catholic and Protestant (as the old RIC had been) that there should be an appropriate proportion of Catholic judges on a Criminal Court of Appeal, that Catholic education should not be interfered with, that a ‘Catholic’ seat for Belfast in the Westminster Parliament should be assured for three years, that the cases of all internees should be heard by a balanced panel, that all houses destroyed in the troubles should be rebuilt at government expense, that the Dublin and Belfast governments should agree to a formal co-operation for a three-year period, and that all members of the Ulster Parliament should take their seats immediately.”31

The last point would obviously require abandonment of the abstentionist position agreed by Devlin and de Valera in their 1921 pre-election pact. June 1922 was not a good month for de Valera when it came to pacts: two weeks later, Collins would break the pact negotiated between the pro- and anti-Treaty factions of Sinn Féin relating to the impending elections for the Third Dáil.

Burke then wrote to Craig, conveying the details of his discussion with Churchill: “… he advised Mr Churchill that the first steps he should take were to insist that Mr Collins and Mr Devlin should recognise the northern government.” He urged the holding of a four-way conference involving Collins, Devlin, Craig and Churchill, “to arrive at a settlement of the Belfast question.”32

Devlin’s supporters tried to secure his involvement in new talks

On 13 June, Burke met with the northern Cabinet Secretary, Wilfrid Spender, who reported to Craig that, “He asked me to write to you at once expressing his view that although a meeting between yourself, Collins and Devlin would be beneficial, any steps taken by you which recognised Collins’ position in Northern Ireland would be very much the reverse.” Spender agreed that “we ought to refuse any representations made through the southern Provisional Government.” However, Burke subsequently protested to Spender that any meeting would have to involve representatives of all parties, including Collins.33

Burke and Douglas were also central to the fact-finding mission of Edmund Macnaghten, a northern Protestant sent by Collins at the end of July to take soundings of the views of northern business and unionist political leaders. Macnaghten met Burke and Dougal and through them, also met James Kennedy, the Belfast County President of the AOH, and Timothy McCarthy, the editor of the Irish News, as well as several Catholic business owners. They also introduced him to Spender, Dawson Bates and John Andrews, Minister of Labour. The hands of Burke and Dougal can clearly be seen in MacNaghten’s report, which said that those he had talked to had expressed, “their most earnest desire that the Catholic gentlemen in the Six Counties who have been elected members of the Northern Parliament should abandon their policy of abstention;” it also reiterated Burke’s suggestion of a meeting involving Craig, Collins and Devlin.34

In the event, nothing came of these attempts to restore Devlin’s relevance.

Hibernians under attack

While these political developments were taking place, Hibernians in Belfast were equally subject to the general wave of attacks being mounted on nationalists.

Hibernians were interned as well as republicans. James McStravick, from Stanfield Street in the Market, was an ex-soldier with fifteen years’ service in the Royal Irish Rifles. He was arrested on 23 May, the day after his son Simon, a member of the IRA, was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment for possession of a revolver and ammunition. The secretary of AOH Division 114, the branch to which McStravick senior belonged, wrote to Dawson Bates: “… we can vouch that he has never been connected with any illegal organisation but on the contrary has been an uncompromising opponent of Sinn Fein in all the local elections…it is within our knowledge that there have been frequent disagreements between Mr McStravick and his son over politics.”35

However, the police insisted that they had information – dubiously, from “a person whom the police suspected was implicated in crimes of an ordinary character, including larceny, hold-ups &c, and for which he was arrested by the IRA” – that McStravick had acted as a guard in the Republican Police jail in St Mary’s Hall. He remained interned until the following December.36

On the night of 17 June, Specials in the Market gave a very pointed response to Dougal’s efforts to enrol Hibernians from the area in the USC:

“During curfew on this (Saturday) night the Hibernian Hall, Cromac St, was raided by Specials … seats were ripped up and some of the regalia destroyed…Floors were lifted up and a life-size picture of Mr Joseph Devlin MP (oil painting) which had been mutilated at a previous raid on the Hall about a fortnight ago was torn into pieces. On the wooden back of the picture a particularly obscene expression was written.”37

While this raid was in progress, the Specials also looted a pub, two doors away in the same street, owned by the defeated Nationalist candidate in the 1921 election, Bernard McCoy: “The Specials raided for two hours … Two bottles of brandy, a bottle of whiskey and two five-shilling pieces which were valued as keepsakes by Mrs McCoy were missing after the raid.”38

Hibernian halls elsewhere in the city were also raided. A Specials’ raid on St Mary’s Hall in February had captured Harkin’s letter to Crumney, offering to supply revolvers and ammunition; the police were now trying to seize the weapons they knew the Hibernians possessed.

Hibernian Halls in Belfast were raided by police searching for arms

In mid-July, in the course of a raid on the house of Thomas McCrory in Massarene Street in the Lower Falls, a number of books were found giving names of members of a division. Naturally convinced that they had just scored a significant intelligence coup against the IRA, the excited police arrested McCrory. On 30 July, the premises of four AOH divisions in Berry Street and King Street were raided. The following day, accompanied by Burke, the AOH’s Kennedy met a senior civil servant in the Ministry of Home Affairs to stress that the organisation “would not countenance preparation for the commission of crime or outrage on the part of its members” and that their divisions were entirely unconnected with those of the IRA: “if any papers were found relating to these Divisions, the police might not suspect that they related to some sinister organisation.”39

While the police were actively trying to find the guns that the Hibernians had in Belfast, at a more senior level, the Hibernians now wanted nothing more to do with guns.

The enthusiasm for armed defence shown by Nugent when initiating the Hibernian Knights the previous November had waned considerably – as he told the June meeting of the BOE, he was exasperated by continual requests for arms and ammunition:

“I cannot appreciate the mentality of the men who appear to think they have only to write to us and their demands in that respect will be met. It would appear as if many of them thought we had an ammunition factory at our disposal. During the past three or four years we sent huge quantities of material all over the North East corner where the fight has been fiercest. We were never tendered anything in payment from any source. Up to one thousand pounds of the cost was paid by the late Mr Redmond, but the Order had to pay for the balance. The difficulties are so great now that I have decided to have nothing more to do in matters of this kind: if there is a necessity for these articles the County Board concerned should raise the necessary funds and make arrangements regarding purchase; they must shoulder their own responsibility.”40

If Nugent had reached the end of his tether regarding weapons, Devlin would soon reach the end of his tenure as the Westminster MP for west Belfast. A British General Election was held on 15 November 1922 but the reduction in the number of northern MPs at Westminster under the Government of Ireland Act, coupled with a fresh round of boundary revisions which this entailed, meant that Devlin had no prospect of retaining the seat he had won in 1918 – the capture of his former citadel by a unionist was inevitable.

In the event, the Unionist Party’s Robert Lynn was the only candidate nominated by any party, so he was returned unopposed. Instead, Devlin stood as an Independent candidate in the constituency of Liverpool Exchange, adjoining that of his Irish Parliamentary Party colleague T.P O’Connor, but he failed to get elected.

Devlin did retain his West Belfast seat in the Northern Ireland General Election of 1925. Having pledged in advance of polling that if elected, he would take his seat in the Parliament of Northern Ireland, he did so at the end of April 1925; “only after the Boundary Commission ended the border nationalists’ hopes of speedy incorporation in the Irish Free State was Devlin able to assert leadership of northern nationalism as a whole on the basis of attendance at the northern parliament.”41

The aftermath of the Pogrom provided more grubby experiences for some of his prominent followers in Belfast.

Burke remained in correspondence with Craig, but primarily for an ulterior motive. Prior to his death in March 1922, Burke’s father had held the post of Deputy Lieutenant of Belfast, a largely symbolic role within British royal officialdom. Burke attempted – without success – to secure the now-vacant position for his brother.42

In May 1923, by now no longer an alderman, Harkin appeared in court accused of fraud, having written several cheques which had then bounced. At the request of his victims, the charges were dropped.43

Summary and conclusions

In 1928, the artist John Lavery painted a portrait of Devlin. The background is intriguing: Lavery chose – obviously with Devlin’s approval – to use the republican tricolour as a backdrop, not the green-and-gold colours that had traditionally been associated with the Irish Parliamentary Party and the Hibernians. By then, the tricolour had been adopted as the flag of the Free State – but the people who Devlin represented were firmly excluded from that state. Given that Devlin declined to take his seat in the First Dáil and also turned down an offer to stand in a Dublin constituency in the August 1923 General Election, the painting is a puzzling commentary on the trajectory of his political career.44

John Lavery’s portrait of Joe Devlin

The British parliament at Westminster and the establishment of a single Home Rule equivalent in Dublin had been the focus of his energy for most of that career. But the Government of Ireland Act and its creation of two parliaments in Ireland, north and south, had imposed partition, his single worst dread. The Parliament of Northern Ireland took shape after the 1921 election, while the second Dáil Éireann was its de facto southern counterpart – Devlin abstained from both. By 1922, still a Westminster MP, the consummate parliamentarian was standing on the wrong battleground.

The negotiations which led to the Treaty and the signing of that document relegated the one-time central figure to a mere bystander as his political opponents on either side of the Irish Sea made decisions into which he had no input. The aftermath of the Treaty further shifted the political dynamic away from his only forum, the British House of Commons, to the cabinet rooms in Belfast, Dublin and London, leaving Devlin an impotent observer.

The best efforts of Burke and Dougal, two of his key middle-class supporters in Belfast, to restore his significance ended in failure – for Devlin, the political tide had gone out: he was a seashell left behind on the beach.

His keenest listeners had once been the west Belfast working-class, but since the outbreak of the Pogrom, they had begun listening more to republican voices. However, the idea that the IRA were alone in using rifles and revolvers to fight off Orange mobs and Specials, while the Hibernians did nothing more than impotently throw paving stones can now be seen as completely misplaced.

The senior leadership of the Belfast IRA had clear political motives for disparaging the role of the Hibernians during the Pogrom. That cadre had come to prominence between 1916 and 1920, a period when Hibernianism was still by far the dominant ideology within Belfast nationalism; many of them harboured bitter memories of the – literally – bruising 1918 General Election campaign, when Sinn Féin election meetings on the Falls Road were broken up by hostile crowds of Devlinite female millworkers. When former officers such as McCorley and McNally came to relate their memories to Ernie O’Malley and the Bureau of Military History decades later, it was almost inevitable that they would deliberately paint their political competitors in a negative light – it suited them to distort the narrative.

Just as Unionists tended to attribute all nationalist violence to “Sinn Fein,” regardless of its actual source, it is also possible that republicans used “Hibernians” as a catchall term of opprobrium to encompass both the AOH and the Irish National Volunteers (INV). While those two undoubtedly had largely overlapping memberships, they were distinct organisations. McNally’s grudging reference to “some of the ex-soldiers” suggests that at least an element of the IRA leadership understood the difference.

In the same way that there was a plethora of armed loyalist groups – the UVF, Ulster Imperial Guards, Crawford’s Tigers and Ulster Protestant Association – the IRA were not the only nationalists with guns. There is evidence that the Redmondite INV was revived in both Derry and Belfast during the summer of 1920; whether members subsequently defected to the more prominent IRA can only be a subject for speculation.

There is more proof when it comes to the armed activities of the AOH. It is now clear that senior Hibernian leaders organised shipments of weapons to Belfast and on one occasion, Nugent even brought the weapons in person. The organisation’s Ulster Catholic Defence Fund was not set up to dispense legal aid or moral support, but to fund the purchase of arms. The AOH also had access to pre-Great War weapons that had belonged to the INV, such as the cache of rifles intended for its Belfast members but stolen by the IRA.

Harkin probably best epitomises the actual role played by Hibernians and the reborn INV. An ex-soldier too young to have been in the pre-war INV, he was secretary of the Irish National Veterans’ Association and also a member of the AOH’s Belfast County Board. Within weeks of the outbreak of the Pogrom, he had organised a picket to protect nationalists in the North Queen Street area; although he claimed the picket was unarmed, one of its members was convicted of using revolvers. As late as August 1921, he was still locating potential black-market sources of arms and ammunition and, strikingly, was willing to share those with the IRA.

In that, he diverged radically from the traditional Hibernian antipathy to republicanism but he brought the same approach to bear in his political role as a Nationalist Party alderman on Belfast Corporation, constantly urging cross-party unity among nationalists. However, in this, he was simply following the example set by Devlin in his pact with de Valera for the 1921 election.

But the most drastic break with the old touchstones of Nationalist Party politics was that spearheaded by Burke and Dougal. While the very idea of co-operation with unionism would have been anathema to pre-war Hibernians, for these well-to-do Catholics, sectarian violence was bad for business – a point also repeatedly stressed to the unionist government by a succession of trade associations and civic society groups in early 1922.45

To Burke and Dougal, co-existence was preferable – provided it was peaceful. But crucially, they had willing listeners in both Belfast and Dublin and their input can clearly be seen in the second Craig-Collins Pact which marked the zenith of their influence. However, the conciliatory ambitions of that agreement in terms of policing reforms, naively proclaimed as “Peace has today been declared” and implausibly aimed at encouraging Catholics to join the Specials, were quickly thwarted as loyalist violence continued.

References

1 Mrs Smyth, no addressee [Sir Ernest Clark?], 9 May 1921, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Names and addresses of alleged Sinn Feiners in Belfast, FIN/18/1/152.

2 Ibid.

3 Lieutenant [illegible] to Sir Ernest Clark, 6 June 1921, ibid.

4 Éamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland, 1890-1940 (Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994), pp63-64.

5 Courts of inquiry in lieu of inquest, Malachy Halfpenny & William Kerr, The National Archives (UK), WO 35/151A/14 & WO 35/153A/47; available online at https://search.findmypast.ie/search-ireland-records-in-military-service-and-conflict

6 Roger McCorley statement, Military Archives, Bureau of Military History, WS0389.

7 John Harkin to Frank [Crumney], 26 August 1921, PRONI, Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, HA/32/1/130.

8 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 17 September 1921.

9 Freeman’s Journal, 29 September 1921.

10 A.C. Hepburn, Catholic Belfast and Nationalist Ireland in the Era of Joe Devlin, 1871-1934 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008), p212; Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmaid Ó Tuama (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2018), p108.

11 Seán MacEntee to Éamon de Valera, 5 November 1921, UCD Archive, Richard Mulcahy Papers, Correspondence with Brigade Commandants, P7/A/29.

12 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, p229.

13 Secretary’s report, 6 December 1921, National Archives of Ireland, Board of Erin (BOE) Minute Books 1906-1925, [microfilm] BR LOUTH 13 2/324.

14 Minutes of quarterly meeting of Board of Erin, 6 December 1921, ibid.

15 Minutes of [resumed] quarterly meeting of Board of Erin, 7 December 1921, ibid.

16 Nadia Dobrianska, ‘Anti-Catholic Pogrom, IRA aggression against Northern Ireland, or the perennial Irish religious war: contested meanings of the intercommunal violence in Belfast, January-June 1922,’ paper delivered at Navigating War and Violence in Twentieth Century Ireland conference, Dublin City University, 4 April 2025.

17 Freemans Journal, 20 February 1922.

18 Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins (London, Arrow Books, 1991), p343.

19 Freemans Journal, 25 February 1922.

20 J.D. Nugent to Irish News, 9 March 1922.

21 Ibid.

22 Proposals for settlement of the disturbances, 25 March 1922, PRONI, CAB/6/37 Disturbances in Belfast, CAB/6/37.

23 Ibid.

24 Proposals for settlement of the disturbances made by certain Roman Catholic leaders in Belfast, 25 March 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

25 Heads of Agreement between the Provisional Government and the Government of Northern Ireland, 30 March 1922, ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, pp214-215.

28 Minutes of meeting between deputation representing the Catholics of Belfast and Messrs Collins, Griffith and Cosgrave, 5 April 1922 & Michael Collins to James Craig, 25 April 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

29 Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, p222; Minutes of Meeting 7 June 1922 & Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, 10 June 1922, PRONI, Formation of Roman Catholic Recruiting Committee to encourage Roman Catholics to join RUC, HA/32/1/142.

30 (Inquiry) Michael Collins to James Craig & James Craig to Michael Collins, both 5 April 1922; (prisoners) Michael Collins to James Craig, 11 April 1922 & James Craig to Michael Collins, 15 April 1922; NAI, D/Taoiseach, Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

31 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, p239.

32 Particulars given by Mr Raymond Burke of his interview with Mr Churchill, n.d., PRONI, Correspondence with R.A. Burke on matters affecting community relations, CAB/6/13.

33 Cabinet Secretary to Prime Minister, 14 June 1922 & Raymond Burke to Cabinet Secretary, 15 June 1922, ibid.

34 Report of Captain E. L. Macnaghten, 7 August 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Captain E.L. Macnaghten: reports on North-East Ulster, TSCH/3/S8998.

35 P.J. Doyle to Minister of Home Affairs, 19 July 1922, PRONI, McStravick, James, Stanfield St, Belfast, HA/5/1494.

36 District Inspector R.R. Heggart to Inspector General, 2 September 1922, ibid.

37 Belfast summary, 17 June 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland: outrages, January-October 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

38 Ibid.

39 Minute sheet (unknown initials), 20 July 1922 & Henry Toppin to Colonel J.M. Haldane, Criminal Investigation Department, 1 August 1922, PRONI, Raids on Ancient Order of Hibernians’ premises at Berry St and King Street, Belfast, HA/32/1/251.

40 Secretary’s report, 8 June 1922, NAI, BOE Minute Books 1906-1925, BR LOUTH 13 2/324.

41 James Loughlin, ‘Devlin, Joseph,’ Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/devlin-joseph-a2557

42 Raymond Burke to Prime Minister, 12 & 18 August 1922, PRONI, Correspondence with R.A. Burke on matters affecting community relations, CAB/6/13.

43 Belfast News-Letter, 19 May 1923.

44 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, p249.

45 See for example correspondence from Belfast Chamber of Commerce, Belfast & District Chamber of Trade, Belfast & North of Ireland Grocers’ Association, and others to Minister of Home Affairs, various dates 1922, PRONI, Proposals for restoration of peace in Belfast, HA/32/1/182.

Leave a comment