Given the abundance of archival material held by Military Archives and other institutions, it is unsurprising that much of the historical writing about the Pogrom from a nationalist perspective has concentrated on the IRA and republicanism more generally. But when the Pogrom began, republicans were a minority among Belfast nationalists – and the IRA were not the only ones with guns.

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes

Joseph Devlin

The key figure in Belfast and northern nationalism was Joseph Devlin, popularly known as “Wee Joe.” Although he was from west Belfast, he was initially elected as an Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) MP for North Kilkenny in 1902, but from 1906 onwards, he was the MP for Belfast West.

Part of his public appeal was that he was as concerned about the labour and social conditions of his constituents from the Shankill Road as those from the Falls Road: “I do not believe in class war…[but] if the intervention of the state should be necessary to compel justice for the workers, then I believe it is the duty of the state to intervene.”1

Devlin had two significant power bases within the IPP. Since 1904, he had been General Secretary of the United Irish League (UIL), a support organisation for the party; a year later, he became Grand Master of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH).

“In essence, Devlin built his early career on routing [Bishop] Henry’s Catholic Association, taking control of the Healyite Irish News in the process. Devlin’s platform oratory not only earned him the nickname ‘Pocket Demosthenes’ but also, with its fusion of militant popular nationalism, democratic shibboleths and working-class welfarism, virtually guaranteed IPP dominance over nationalist Belfast for a political generation.”2

In contrast to republicans, for whom the traditional enemy had always been Britain, Tim Wilson has said that:

“To the IPP/Hibernians, their principal opponents remained the Protestant/unionist community. Ulster Catholics who supported the IPP were prepared to accept a ‘Home Rule’ Irish state that would remain subordinate to a wider federalised United Kingdom, but which would have the advantage of protecting them from local Protestant/unionist domination.”3

In the campaign for the 1918 General Election, a partial pact between the IPP and Sinn Féin was brokered by Cardinal Michael Logue to cover eight northern constituencies in which it was feared that splitting the nationalist vote in a first-past-the-post contest might allow the election of a unionist candidate.

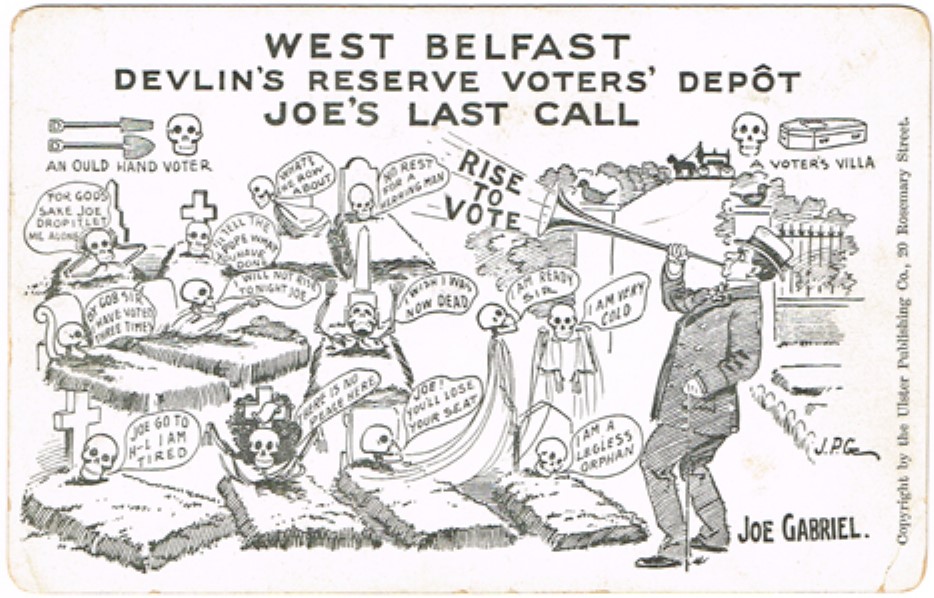

A satirical unionist postcard commenting on Joe Devlin’s ability to get the vote out

However, in the re-drawn Belfast Falls constituency, with much of its Shankill component excised into a new Belfast Woodvale constituency, there was no such risk. Here, there was a straightforward intra-nationalist contest between the IPP’s Devlin and Sinn Féin’s Éamon de Valera. Despite the latter’s credentials as a surviving commander of the 1916 Easter Rising, Devlin won comfortably with a majority of more than two-to-one: 8,488 votes against de Valera’s 3,425.

The pact meant that four IPP candidates, including Devlin, were returned for six-county constituencies as well as three from Sinn Féin; however, in two other constituencies not covered by the pact, Sinn Féin out-polled the IPP in South Tyrone and almost matched it in Londonderry (county) South. These were portents of what was to come.

The prospect of partition had been on the political agenda since before the Great War, but as yet, Sinn Féin had no strategy for how to avert the threat, other than an all-Ireland platform of abstention from the UK parliament in Westminster. In that context, as Éamon Phoenix noted:

“…it was ironic that, in their dread of partition, a substantial section of northern nationalists had entrusted their fate to a new generation of politicians in whose scheme of things partition seemed to become more and more relegated to the realm of metaphysics.”4

Across Ireland, a landslide saw Sinn Féin sweep aside the IPP, winning 73 seats and leaving the IPP with a rump of just seven MPs – as well as the four seats in the six counties, IPP seats were retained in East Donegal and Waterford, and T.P. O’Connor was returned as an IPP MP for a largely Irish constituency in Liverpool.

All successful candidates from across Ireland were invited to take their seats at the inaugural meeting of a new republican parliamentary assembly, Dáil Éireann, in January 1919. Like the unionist leader Edward Carson, Devlin did not respond to the invitation.

The Ancient Order of Hibernians

The AOH had its roots in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Catholic agrarian societies such as the Defenders and the Ribbonmen. It was a fraternal, oath-bound organisation, “devoted to the idea of a Catholic Ireland, one where the Catholic Church and its priests were respected and venerated, and all the heretical forces of Freemasonry and Orangeism repulsed.”5

The structure of the AOH was based on local branches, known as divisions, grouped under district, county and provincial boards. Its governing body was the Board of Erin (BOE): “The BOE was…overwhelmingly successful in Ireland and Britain with Irish Party MP Joe Devlin as President and John Dillon Nugent, who minuted the board’s meetings and directed the organisation’s day-to-day operations, the national secretary.”6

At the turn of the twentieth century, the primary activities of the AOH were political and social; in 1912, it took on an additional benevolent role when it became an approved society under the terms of the new National Insurance Act – in the event of a member who paid weekly contributions becoming ill, the AOH would cover their medical costs and pay weekly allowances as long as they remained ill.

As regards politics,

“From the outset the paper [the Hibernian Journal] claimed that the Order was a national body, a part of the National Organisation or movement yes, but not its leader… And anyway, according to Devlin, it was and had always been their policy to loyally back any national movement which commanded the support of the majority of the Irish people. The Journal never tired of printing compelling reasons to support the National Organisation’s masthead, the Irish Parliamentary Party.”7

The AOH also played an important non-political role in members’ everyday lives:

“Hibernian social life had three main aspects: entertainment, organisation and teaching…For most Hibernians it meant participating in a demonstration, showing up at a meeting and catching a concert…Hibernian clubs and halls were the lynchpins for all three strategies, providing a platform for dances, meetings, and lectures.”8

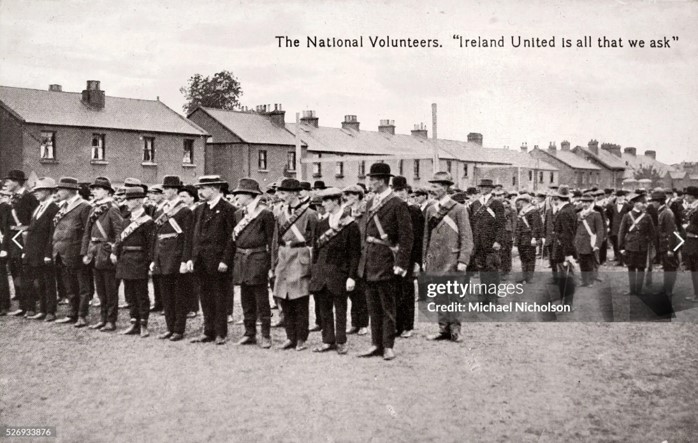

Uniformed Hibernians in Glenavy, Co. Antrim

The highlight of the Hibernians’ calendar was 15 August, when they held their annual Lady’s Day parades, preceded by bonfires:

“As far as ceremonial went the resemblances between the Orange Order and the Board of Erin brotherhood were striking, except that green replaced orange, its spectral near-neighbour on sashes, banners and flags…the twelfth of July that celebrated each year the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne had its Hibernian counterpart in the fifteenth of August, the feast of the Assumption of Our Lady bodily into heaven, thereby indicating that the AOH was not exactly open to all applicants.”9

Given these similarities, it was probably no surprise that the trade union leader Jim Larkin described the AOH as the “Ancient Order of Catholic Orangemen.”10

The social life of the AOH also had other, darker dimensions, as Wilson has observed: “…the Hibernians in Ulster enjoyed a (carefully cultivated) reputation as ‘hard men’…Their rallies had a reputation for serious drinking and recreational violence.”11

An incident in 1912 highlighted this side of the AOH. On 29 June, a Presbyterian Sunday School outing of 500 children to Castledawson in Derry was returning to the train station when they encountered 300 Hibernians coming from the station as they returned from a rally in Maghera:

“…there were no party cries from the children and the only things they had on display were a few banners bearing scriptural texts – and one Union Jack. The last item was enough to provoke a riot because one of the Hibernians, a man called Craig, rushed across to try and seize it. He was caught and pushed back by one of the small number of police accompanying the two parades. This was the signal for waves of AOH members to pour into the children punching, kicking and throwing stones and trying to get their hands on the banners. News of the affray reached Castledawson very quickly and soon crowds of Protestant men were streaming to the spot engaging the Hibernians with sticks and pitchforks.”12

That Hibernian riot had repercussions in Belfast three days later:

“…a serious melee broke out at the Belfast shipyard of Messrs Workman, Clark & Co, several men having to be hospitalised. According to the Belfast News-Letter, a riveter, two of whose children had been injured at Castledawson, got into an altercation with a Roman Catholic workman. The Irish Independent reported how groups of Protestant workmen then marched round the yard’s departments, ordering their Catholic colleagues to leave. A large number did, those declining to do so being roughly treated.”13

In parliament, Devlin denied that the Hibernians had attacked the children and instead claimed that the Hibernians had been attacked by Orangemen. This came as little surprise to some observers: “As the president of the AOH, Devlin was undoubtedly the bete noire of contemporary non-sectarian nationalists. The Belfast MP did not necessarily seek to save the Order from ‘the morass of sectarianism’ so much as harness this element.”14

According to the Hibernian Journal, the organisation’s in-house magazine, available only to members, the AOH had a membership of 58,911 in Ireland in April 1913; 40% of these were in Ulster. Perhaps surprisingly, within Ulster, Belfast was not the main centre of Hibernian strength – there were only 2,005 AOH members in the city, compared to 5,210 in Donegal. Membership fell off during the Great War, due to a combination of factors: the Home Rule Act was now on the statute book, while the Easter Rising had created a new pole of attraction, leading AOH members to defect to Sinn Féin. By September 1917, national Hibernian membership had dropped to 36,264, while Ulster now accounted for 46% of the total; Belfast bucked the trend of decline, with AOH membership in the city remaining steady at 2,026.15

Police estimates for the membership of nationalist organisations were often hilariously inaccurate; however, those for Belfast in June 1920, although wildly inflated, do point to the UIL and AOH as being the dominant strands within nationalism in the city: while Sinn Féin only had 980 members in nine clubs, the UIL had 6,035 members in ten branches and the AOH supposedly had 8,000 in 25 divisions.16

Illustrating the wide gulf between police beliefs and reality, the AOH’s own membership figure for Belfast at this time was actually 2,671.17

But more importantly than numbers, in relation to the AOH, as Wilson observes: “What that rank and file thought and said tended to be noticeably more hard-line than the conciliatory pronouncements of Joe Devlin and his IPP/Hibernian lieutenants.”18

The outbreak of the Pogrom

Sectarian violence erupted in Derry in late June 1920 – in the course of a week, twenty people were killed there. The AOH’s Nugent gave an exaggerated report of the organisation’s impact on these events to a meeting of the BOE in early September:

“The members of the Board will recollect that in 1912 and 1913, we purchased a large quantity of ammunition, riffles [sic], pistols and machine guns. Two of the latter were sent to Belfast and two to Derry at the time. As soon as I heard of the trouble in Derry I tried to get in touch with Ald. Doherty, our local representative, but [having] sent several wires and letters I could get no reply indicating that ‘the lines of communication were cut off.’ Subsequently I got in touch with Mr G. Doyle, Strabane, and arranged that the machine guns should be brought to Derry where they were in action on the Sunday night and Monday morning. A report appeared in the ‘Irish Times’ and other papers suggesting that the Catholic side must have employed machine guns. The result, however, was that on the Monday evening the white flag was hoisted by the Protestant side and mercy sought. Some forty or fifty riffles which were stowed away in the Hibernian Hall were taken out in broad day light and so frightened were the other side that their collapse immediately followed.”19

The reality was more prosaic: far from the UVF being machinegunned into submission, peace was restored when British military reinforcements were sent into the city, martial law was declared and a conciliation committee was established by a Sinn Féin councillor acting alongside some of his Unionist Party counterparts.20

Far from the Hibernians forcing the UVF to seek “mercy,” British troops restored order in Derry in 1920 (© Derry of the Past Facebook group)

One unheralded outcome of the violence was that the then-moribund Irish National Volunteers (INV) were revived in Derry. On the outbreak of the Great War, the Irish Volunteers had split over the issue of joining the British Army – the majority followed the calls of IPP leader John Redmond, echoed by Devlin, to enlist, becoming known thereafter as the INV. After the Derry rioting, Nugent said, “The Sinn Feiners endeavoured to organise their Volunteer force and Bro. Doherty at once took the matter in hands and re-established the Irish National Volunteers, on the first night enrolling 50 ex-soldiers.”21

An obvious implication of this is that if the INV were restarted in Derry, then it is very likely that the same thing happened in Belfast, where Catholics were in a minority of the population, thus more vulnerable, and the AOH was more numerous than in Derry.

Nearly all accounts of the initial outbreak of violence in Belfast on 21 July 1920 reference Séamus McKenna, then a junior officer in the IRA: “The pogrom broke out in Belfast in July 1920 and at the beginning the Volunteers were ordered not to take any part in what was regarded at that time as fratricidal strife.”22

However, the IRA may not have been as uninvolved as McKenna believed. A newspaper report suggests that they were in action as early as the day after the initial outbreak: “Irish Volunteers patrolled the Falls Road and urged nationalists to keep away from the areas in which trouble was raging.” Seán McConville was a member of the IRA and he described how, “The pogrom rapidly spread all over the city. Our Company was detailed for work guarding Clonard Monastery.”23

A mob loots a shop in Clonard in July 1920 (Illustrated London News, 31 July 1920)

One of the Catholics killed in Clonard on the day after the shipyard expulsions was a member of the IRA: Joseph Giles, killed in Bombay Street on 22 July. John McCartney, who was shot dead in nearby Kashmir Road on the same day, was named as an IRA fatality almost two decades afterwards, although contemporary accounts of his funeral suggest that his loyalties may actually have lain elsewhere:24

“The cortege was extremely large and representative and included prominent Belfast Nationalists and members of the Belfast Corporation, a notable feature also being the presence of the Irish National Veterans’ Association members, who (under the direction of Alderman John Harkin and Mr Frank Harkin) marched in processional order. The hearse, which was drawn by deceased’s friends and the general public, was followed by the coffin, which was carried to the graveside on the shoulders of the Veterans and general mourners…The guard of honour was in charge of Mr W[illia]m Skeffington (Irish National Volunteers).”25

This account of McCartney’s funeral confirms that the INV were re-established in Belfast as well as in Derry. As many of the members of the Irish National Veterans’ Association would have been in the INV before the Great War, there were clear overlaps between the two bodies. A senior IRA officer later alluded to them also being involved in armed conflict in Belfast – Tom McNally, Quartermaster of the 3rd Northern Division, told Ernie O’Malley that ”We had to rely on the Irish Volunteers and on some of the ex-soldiers.”26

Irish National Volunteers in Dublin in 1919; the organisation was revived in Derry and Belfast in 1920

John Harkin was a dynamic rising star of the Nationalist Party in Belfast. Although he lived in Ardmoulin Street, off Divis Street, he had been elected to Belfast Corporation in January 1920 for the Victoria ward, which at the time straddled both banks of the River Lagan, taking in parts of Ballymacarrett in the east of the city as well as North Queen Street and the docks on the other side; by virtue of topping the poll, he had been awarded the honorific of alderman. Harkin had been in the army for three years during the Great War, serving with the 7th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in the 16th (Irish) Division. Even though he was only aged 21, he was already president of the John Redmond branch of the UIL in Clonard and a member of the Belfast County Board of the AOH. He was also secretary of the INVA – in December 1920, he was one of a delegation from various ex-servicemen’s associations which met the Lord Mayor of Belfast to discuss veterans’ welfare and pension rights; ironically, the delegation also included Robert Boyd of the Ulster Ex-Servicemen’s Association, who some months later would initiate the founding of the loyalist Imperial Guards.27

In response to the July violence, Nugent said in his “Secretary’s Letter” column in the following month’s Hibernian Journal that, “In view of the savage onslaught on Catholics in Belfast and N.E. Ulster generally, and the calling out of Carson’s Volunteers, it may become necessary for our Order, at any moment, to establish a Brigade for the defence of the lives and property of Catholics in N.E. Ulster.”28

In September, the AOH launched an Ulster Catholic Defence Fund via the Hibernian Journal. This was separate to the Expelled Workers’ Relief Fund established by trade unionists and Belfast Labour party activists, with support from Devlin and the Catholic Bishop of Down & Connor, Joseph MacRory. That was a very public fund, for which AOH divisions ran fundraising concerts and collected subscriptions.

The name of the AOH’s unconnected internal fund clearly suggests that its objective was to provide more than just charity, so it may represent an early step in bringing Nugent’s “Brigade” idea to fruition – as the weekly “Hibernianism” column in the Irish News darkly noted, “There are ways and means of teaching the pogromists a lesson. Let us all avail of these.” By October, the Defence Fund had already raised £582, or more than £22,000 in today’s terms.29

After a lull, rioting and killings returned to Belfast in the aftermath of the IRA’s killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn on 22 August. Nugent once more sprang into action:

“On Monday week last [30 August 1920] I proceeded to Belfast bringing with me a number of pistols and ammunition, and the following day Mr Bergin and Mr Whelan made the same journey taking a further large supply. One day after the Hibernians and Catholic party were thus armed in Belfast the fighting ceased.”30

While Nugent was once more over-emphasising the AOH’s impact, it appears that while the IRA was initially hesitant to become embroiled in “the usual fratricidal strife,” the AOH were busy filling the vacuum on the nationalist side.

Further evidence of early armed Hibernian or INV involvement can be seen in the report of a court martial held on 10 September. Thomas Duffy was accused of using two revolvers to shoot at loyalists in Great Georges Street, off North Queen Street, on 30 August, the day of Nugent’s arms delivery.

Duffy pleaded not guilty, naturally insisting that he had not been armed, while Harkin appeared as a witness for the defence:

John Dillon Nugent, Secretary of the AOH: personally brought guns to Belfast for use by Hibernians (© National Library of Ireland)

“In response to the appeal of the Lord Mayor of Belfast witness organised a civilian picket to help to maintain order, and on the 30th August the accused was one of this picket. The patrol was allotted certain duties, one section attending to the storage of furniture of persons who were evicted…Witness posted the accused at this work shortly after eight and saw him regularly about every fifteen minutes until he was relieved about 9.30pm…The accused had no arms.”31

Great Georges Street (© National Museum of Northen Ireland, Welch Collection)

Despite this evidence, Duffy was found guilty on the arms charge and sentenced to twelve months’ hard labour. Although Harkin’s attempt to provide an alibi failed miserably, this shows that the Hibernians, the INV, or both were organising resistance in nationalist areas, in addition to the IRA; the assertion in court that it was unarmed resistance is most charitably described as dubious.

Nor was Duffy’s an isolated case: research conducted for a previous blog post on firearms offences established that from July to December 1920, of eleven nationalists of any hue convicted for possession of weapons or attempted murder, only four were identified either at the time or subsequently (through nominal rolls or applications for Military Service Pensions) as being members of the IRA. The corollary is that the majority must have been affiliated to the Hibernians and/or INV.

Wilson is therefore correct when he says, “Indeed, it seems fairly clear that probably the majority of the Catholic rioters in Belfast were Hibernians, and not Sinn Feiners, despite what their loyalist opponents repeatedly alleged.”32

He goes on to state:

“The Ancient Order of Hibernians Ulster primarily stood for communal defence by deterrence. Hibernians attempted to mobilize the Catholic community in a mimetic politics of confrontation to match those of the Orange Order. It was, therefore, entirely to be expected that, when serious intercommunal rioting broke out in Derry and Belfast during the summer of 1920, it was largely the Hibernians who took the lead from the Catholic side.”33

The Hibernians also provided other forms of support: “In September 1920 the National Club [an AOH-owned premises in Berry Street in the city centre] was vacated to provide temporary accommodation for some of the thousands of Catholics driven out of their homes.” Other Hibernian Halls were also used to house refugees.34

If the Hibernians had taken the lead as Wilson suggests, that left the IRA in a position of trying to catch up during the autumn – this included the acquisition of arms. Roger McCorley, later O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, described how this included stealing weapons destined for the Hibernians:

The AOH National Club in Berry Street was used to house Catholics driven from their homes

“On the outbreak of the pogrom we had got information through our Intelligence that a Catholic clergyman outside Belfast had sixty Martini-Enfield rifles which had been the property of the old National Volunteers who were no longer in existence. He had sent information into Belfast to the Hibernian element that he had these arms and he asked them to call out and collect them for use in the defence of the nationalist areas. The information from our Intelligence Department was such that we were able to call out at the appropriate time and collect these arms ourselves. The clergyman instructed our man, he being under the impression that we were of the Hibernian element, that under no circumstances were these arms to get into the hands of the IRA. Our people assured him that they would make sure no one would get control of the arms other than themselves.”35

A reference provided for a Military Service Pension application suggests that this coup was achieved by Ben Donegan, an IRA Intelligence Officer and Harkin’s neighbour in Ardmoulin Street – Harkin lived at number 7, Donegan at number 12.36

Martini-Enfield rifles destined for the Hibernians in Belfast were stolen by the IRA (© Swedish Army Museum)

At Westminster, Devlin was a fierce critic of British government policy in Ireland. On 9 September, the British cabinet acceded to unionist urgings and decided to proceed with the formation of a Special Constabulary, for which recruitment began on 22 October. Devlin bitterly attacked the plan in Westminster three days later:

“The Chief Secretary is going to arm pogromists to murder Catholics…The Protestants are to be armed, for we would not touch your special constabulary with a forty-foot pole. The pogrom is to be made less difficult. Instead of paving stones and sticks, they are to be given rifles.”37

In the aftermath of an IRA attack on a British bread-lorry in Dublin on 20 September 1920, an IRA Volunteer, Kevin Barry, had been captured and sentenced to death. Perhaps surprisingly, Devlin spoke directly to the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, appealing for clemency for the young republican; according to A.C. Hepburn, both Lloyd George and the British Lord Chief Justice were inclined to grant a reprieve, but the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Hamar Greenwood, insisted that the execution should go ahead. Barry was hanged on 1 November.38

Devlin’s last stand against partition

In the period preceding the final passage of the Home Rule Bill in 1914, there had been discussions about the possibility of the legislation only being applied to the southern part of Ireland. However, as Martin O’Donoghue has highlighted, the AOH’s head-in-the-sand approach to the issue even applied to its own private publication: “Exclusion of Ulster counties was the dog that did not bark in the Hibernian Journal between 1912 and 1914.”39

After the Easter Rising, the British government returned to the Irish question and Lloyd George drew up a plan for implementing Home Rule that incorporated exclusion, but on a typically ambiguous basis: “Speaking to Redmond and Carson separately, George persuaded the former to accept, in principle, a Home Rule scheme based upon the exclusion of the six counties, with partition merely temporary. Carson, meantime, was assured of the scheme’s permanency.”40

Devlin was instrumental in securing a vote in favour of the proposal at a conference held in St Mary’s Hall in Belfast in June 1916, attended by nationalist MPs, councillors, clergy and delegates from the UIL, AOH and Irish National Foresters. Temporary exclusion of six counties was felt to be a price worth paying if it meant the final delivery of Home Rule.

The Government of Ireland Bill was the output of a British cabinet committee set up in late 1919 in a final attempt to introduce Home Rule. “By early November, the Belfast Nationalist MP had absolutely no doubt that the administration’s Bill would entail partition.”41

He wrote to Bishop Patrick O’Donnell of Raphoe on 13 February 1920:

“This will mean the worst form of partition and, of course, permanent partition…we Catholics and Nationalists could not, under any circumstances, consent to be placed under the domination of a parliament so skilfully established as to make it impossible for us to be ever other than a permanent minority, with all the sufferings and tyranny of the present day continued, only in a worse form.”42

The Government of Ireland Bill was introduced at Westminster in early 1920 (Illustrated London News, 10 April 1920)

The key provision of the Bill was the establishment of separate Parliaments of Northern and Southern Ireland, based in Belfast and Dublin respectively. Northern Ireland would consist of six counties – Antrim, Armagh, Down, Londonderry, Fermanagh and Tyrone – rather than the nine counties of historical Ulster; unionists had argued for the exclusion of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan. The imperial parliament at Westminster would retain control over defence, finance, foreign affairs and international trade, but in other matters, the two entities would be self-governing. Both would continue to send MPs to Westminster, although in reduced numbers.

While Devlin and the remaining IPP MPs boycotted the initial stages of the Bill’s passage through parliament, there was a split within nationalism in the north: “a large section of opinion in the western parts of the six counties was prepared to accept a partition based upon the exclusion of the four counties with unionist majorities.”43

Devlin dropped his boycott to furiously oppose the passage of the Bill with his usual oratorical flair, describing it as “conceived in Bedlam,” “ridiculous” and “fantastic,” adding: “They have created, for the first time in history, two Irelands. Providence arranged the geography of Ireland, and the Right Honourable Gentleman [Lloyd George] has changed it.”44

When it came to the final reading of the Bill on 11 November 1920, he saw the arithmetic that would apply and was appalled at the lack of protection for minority rights in the legislation:

T.P. O’Connor: said partition would “make this tragic servitude of a people complete”

“Will the House believe that we are almost 100,000 Catholics in a population of 400,000 (in Belfast)? It is a story of weeping women, hungry children, homeless in England, houseless in Ireland. If that is what they get when they have not their Parliament, what may we expect when they have that weapon, with wealth and power strongly entrenched? What will we get when they are armed with Britain’s rifles, when they have cast round them the imperial garb, what mercy, what pity, much less justice or liberty will be conceded to us then?”45

His parliamentary colleague T.P. O’Connor provided a grim forecast of the prospects for nationalists in the new polity:

“They are to have courts of law which will be manned by their political enemies, they are to have cabinet ministers who are to be drawn from their political opponents. Finally, and to make this tragic servitude of a people complete, they will have their political enemies armed, disguised as policemen, but really the armed forces of their political enemies.”46

With the Pogrom then almost five months old, Devlin referenced it when he had his final fling against the Bill on 16 December 1920:

“If, under your own imperial control, they can hunt innocent men from their employment for no crime but that of their religion or their politics, if they can burn down houses without protest under your imperial regime…what is the vision of the future to be for these people under the regime of the malefactors who are preparing these outrages upon the poor people I have ventured to describe…”47

Having been passed by both Houses of Parliament, the Government of Ireland Act was signed into law by King George V the day before Christmas Eve 1920.

The 1921 General Election

The first step towards implementing the Act was to hold elections in both jurisdictions – they were scheduled for 24 May 1921. In the north, the IPP became known as the Nationalist Party, but the fact that the Act had made partition an established fact meant that the party began the electoral campaign in a debilitated and demoralised state. This became apparent as the process of selecting candidates at local conventions began:

“For Devlin, who before 1914 had presided over one of the most efficient political machines in Europe, these conventions proved a bitter sight. At one in Tyrone over which he presided arrangements had been made for 400 delegates, but only about 40 turned up – ‘mostly old men…It was tremendously disappointing.’”48

Encouraged by Bishop MacRory, Devlin and de Valera agreed a pre-election pact between the Nationalist Party and Sinn Féin: each would field an agreed maximum of twenty-one candidates, each would encourage its supporters to transfer second preference votes to the other and both parties would refuse to take their seats in the new parliament.

Joe Devlin (L) and Éamon de Valera (R) agreed a pact for the 1921 General Election

However, the Nationalist Party, through lack of funds and manpower, struggled to field candidates – while Sinn Féin had twenty, it only had twelve. Devlin stood in both Belfast West and Antrim and was also selected to stand in Armagh but, conscious of the negative image that would be portrayed if he stood in so many constituencies, he prevailed on the AOH’s Nugent to go forward instead. Harkin’s brother Frank stood in Belfast North, while elsewhere, five of the Nationalist Party’s candidates were publicans and one was a barrister and a former editor of the Irish News.49

Devlin made a bold prediction at a final rally the day before polling: “They have attacked my citadel in west Belfast. I will storm their stronghold in Antrim.” Polling day itself was marked by violence – Alderman Harkin was dragged from a car and beaten up by a hostile crowd at the junction of the Newtownards Road and Pitt Street.50

The results showed that while Devlin did secure a seat in Antrim, his citadel actually came very close to being conquered: the majority of 5,063 that he had secured over de Valera in Belfast Falls in 1918 shrank to just 1,708 against the joint challenge of Sinn Féin’s candidates, Denis McCullough, the leader of the Belfast Irish Volunteers who mobilised in Dungannon for the 1916 Easter Rising, and Seán MacEntee. Results in constituencies elsewhere in the city that were unwinnable for any kind of nationalist illustrated the extent to which Sinn Féin had eclipsed Devlin’s party: in Belfast East, the Nationalist Party’s T.J. Campbell only got 40% of the combined total of Nationalist and Sinn Féin votes; in Belfast South, the Nationalist Bernard McCoy got 38%; while in Belfast North, Frank Harkin trailed Sinn Féin’s Michael Carolan by 32% to 68%.51

Devlin’s Belfast West was the only constituency in which a Nationalist Party candidate topped the poll. Nugent was elected in Armagh but with less than half the combined votes of Michael Collins and his running mate, Frank Aiken. That pattern was repeated in Londonderry, Down and most starkly in the cockpit of Fermanagh & Tyrone, where three Sinn Féin candidates were elected as opposed to one Nationalist, with the five Sinn Féin men securing 19,964 more votes than their two Nationalist rivals. In total, although each party won six seats, Sinn Féin received 104,417 votes to the Nationalist Party’s 60,577.52

Nugent was understandably bitter in the aftermath, deploying a convoluted application of mathematics when addressing a meeting in Armagh on 19 June:

“The allegation might be made that the election was fought, to secure a verdict for a Republic. Let them examine the result. The Unionists secured a total poll of 25,715 [in Armagh]. These were cast against a Republic. Undoubtedly the votes cast by the Nationalists, were likewise anti-Republic; thus, the total anti-Republic votes polled in the county amounted to 32,573, while the inclusive Republican vote was 13,917, showing a majority in the county against a Republic of 18,618. What, then, was the election fought for? If it was not against partition, nor to secure a verdict for a Republic, nor even yet to keep out the Nationalist candidate – what then was the object of the contest?”53

In contrast to Nugent’s feeble denial of reality, Phoenix painted an accurate picture of the new political landscape:

“Only in west Belfast did constitutionalism survive as a credible force, but even there its appeal was largely to the Catholic business class and older generation, devotees of the much-loved Joe Devlin…But like their mentor Devlin, they avoided any criticism of the movement whose spokesmen were now publicly acknowledged as the accredited representatives of Irish nationalism.”54

Part 2 of this post will review events between the election and the end of the Pogrom

References

1 A.C. Hepburn, Catholic Belfast and Nationalist Ireland in the Era of Joe Devlin, 1871-1934 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008), p203.

2 Fergal McCluskey, ‘“Make way for the Molly Maguires!” The Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Irish Parliamentary Party, 1902-14’ in History Ireland, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January/February 2012), pp32-36.

3 Tim Wilson, Frontiers of Violence: Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918-1922 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010), p125.

4 Éamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland, 1890-1940 (Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994), p56.

5 Daniel McCurdy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians in Ulster’, (PhD thesis, Ulster University, 2019), p264.

6 Martin O’Donoghue, ‘Faith and fatherland? The Ancient Order of Hibernians, northern nationalism and the partition of Ireland’ in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 46, No. 169 (May 2022), pp77–100.

7 McCurdy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians in Ulster’, pp25-26.

8 Ibid, p259.

9 Seán McMahon, Wee Joe: The Life of Joseph Devlin (Belfast, Brehon Press, 2011), p99.

10 Ibid, p99.

11 Wilson, Frontiers of Violence, p127.

12 Michael Foy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians: an Irish political-religious pressure group 1884–1975’ (MA thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast, 1976), p125.

13 McCurdy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians in Ulster’, p204.

14 Ibid, p198.

16 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, p212. It should be noted that the numbers in the police reports were slavishly copied from one month’s report to the next; for example, identical figures were still being used in the report for May 1921, during which the General Election was held: City Commissioner for Belfast, Monthly Confidential Report for May 1921, 1 June 1921, The National Archive (UK), CO 904/115.

17 Secretary’s report, 9 June 1920, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), Board of Erin (BOE) Minute Books 1906-1925, [microfilm] BR LOUTH 13 2/324. I am very grateful to Martin O’Donoghue for his invaluable advice on how to access this material.

18 Wilson, Frontiers of Violence, p127.

19 Secretary’s report, 7 September 1920, NAI, BOE Minute Books 1906-1925, BR LOUTH 13 2/324.

20 Adrian Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2018), p100.

21 Secretary’s report, 7 September 1920, NAI, BOE Minute Books 1906-1925, BR LOUTH 13 2/324.

22 Séamus McKenna statement, Military Archives (MA), Bureau of Military History (BMH), WS1016.

23 Freeman’s Journal, 23 July 1920; Seán McConville statement, MA, BMH, WS0495.

24 (Giles) Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001), n37 p283; (McCartney) David Matthews, MA, Military Service Pensions Collection, MSP34REF60258. No Military Service Pensions applications by relatives of either Giles or McCartney have yet been released.

25 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 31 July 1920.

26 Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmaid Ó Tuama (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2018), p108.

27 Belfast News-Letter, 19 January 1920; Seán MacEntee to Éamon de Valera, 5 November 1921, UCD Archive, Mulcahy Papers, Correspondence with Brigade Commandants, P7/A/29; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 1 January 1921.

28 Hibernian Journal, August 1920.

29 Ibid, October 1920; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 18 September 1920.

30 Secretary’s report, 7 September 1920, NAI, BOE Minute Books 1906-1925, BR LOUTH 13 2/324.

31 Northern Whig, 13 September 1920.

32 Wilson, Frontiers of Violence, p128.

33 Ibid, p128.

34 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, p217; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 4 September 1920.

35 Roger McCorley statement, MA, BMH, WS0389.

36 Benedict Donegan file, MA, Military Service Pensions Collection, 24SP12787; Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Donegan, Benedict, Ardmullan St [sic], Belfast, HA/5/2319.

36 McMahon, Wee Joe, p186.

37 Hepburn, Catholic Belfast, pp221-222.

38 O’Donoghue, ‘Faith and fatherland?’

39 McCurdy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians in Ulster’, p233.

40 Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, p71.

41 Ibid, p76.

42 Ibid, p78.

43 Ibid, p79.

44 Ibid, p96.

45 Ibid, p103.

46 Ibid, p102.

47 Foy, ‘The Ancient Order of Hibernians’, p151.

48 Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, p123.

49 Irish News, 23 May 1921; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 28 May 1921.

50 http://www.election.demon.co.uk/stormont/stormont.html; Belfast News-Letter & Northern Whig, 27-30 May 1921.

51 Ibid.

52 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 25 June 1921.

53 Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, pp142-3.

Leave a comment