Estimated reading time: 25 minutes

Introduction

The files of the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) have many accounts of the wounds and illnesses suffered by members of the IRA and Cumann na mBan as a result of their republican activities. However, for them, as well as the police and military against whom they were fighting, the risk of being killed or wounded was an occupational hazard which they chose to accept. No such choice was offered to the 415 non-combatants who were killed during the Pogrom.

Although some people were charged with murder and appeared in court, nobody was ever convicted for the killing of any of those 415 people.

Only a small handful of people were charged with the attempted murder of someone during the Pogrom. Their intended victims told the courts what they had gone through – their testimony thus represents an opportunity to tell the stories of people who were shot but survived.

For the purposes of this post, court cases involving policemen who were targeted and the MSPC files of republican casualties have deliberately been excluded; instead, the focus is on ordinary people who were simply going about their everyday lives when someone else tried to kill them.

Sarah Bannon

On 29 March 1921, Sarah Bannon was in her home at 3 New Lodge Road, near its junction with North Queen Street and facing Vere Street on the opposite side of the street; hearing gunshots, she went into the front room to bring two of her children out of the room – she looked out the window:

“I saw a young man shooting. He had a shooting affair in his hand. When I looked through the window first I saw nobody. I then saw a man coming out of a door and he fired up Vere Street in the direction of my house. Something struck my mouth and I remember no more.”1

Sarah Bannon’s daughter Lizzie was standing beside her when she was hit – she said the man who fired the shot stepped out of a doorway in Vere Street with a lamp lit above it; other eyewitnesses who lived in Vere Street identified that man as being Thomas Saunders who lived in number 34. However, other residents of that street told the court that Saunders was not the man who had fired the shot; two other witnesses said they had been with Saunders in a bookies near Dock Street, on the far side of York Street, at the time of the shooting.2

He was acquitted.

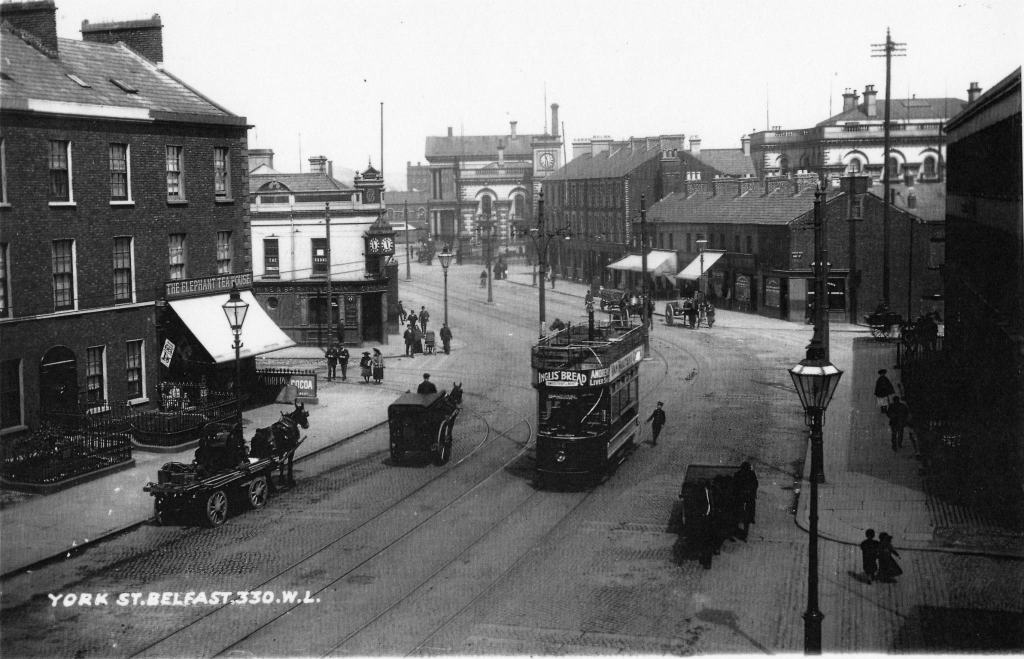

North Queen Street (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Welch Collection)

Patrick McGurnaghan

One of the Vere Street eyewitnesses who said they had seen Saunders with a revolver was Patrick McGurnaghan – that may have been the reason why he was subsequently targeted eight months later.

On the afternoon of 24 November 1921,

“When I came near my own door I saw the prisoner standing near the corner of Dale Street. He was wearing a blue vest and a blue pair of trousers. He had no coat or cap. He had a rifle in his hands. He was about 25 or 30 yards from me. He bent down and fired a shot. The rifle was pointed towards North Queen Street which was towards me. I felt a stinging pain and discovered that I had been shot. The bullet entered below my right breast and passed out the back.”3

The boy recognised James Galbraith, who also lived in Vere Street, as the man who had shot him. McGurnaghan’s sister lived next door – she said the wounded boy staggered into her house, she looked down the street and saw Galbraith kneeling with a rifle. Minnie Parks, another neighbour, had identified Saunders as being the gunman in the previous incident; she also said she had seen Galbraith with the rifle and had shouted at him, “All right Galbraith, you’ll not get away with that.”4

Alibis for Galbraith were provided by various members of the Imperial Guards, who said that he was part of a detachment that had marched in the funeral cortege of another Imperial Guard who had been killed.5

He was found not guilty.

John McArdle

Foundry Street in Ballymacarrett, with a predominantly Catholic end nearer to the Newtownards Road and a mainly Protestant end towards the nearby railway line, was a constant scene of tensions and violent clashes.

John McArdle did not actually give evidence of being shot – when the case came to be heard, he was still in hospital; instead, his mother told the court: “He was wearing the boot produced which has now a hole on either side of the ankle.”6

Boys gathering stones to use as ammunition (© Corbis)

Patrick Magee said that a group of boys had been playing football in O’Kane’s Lane off Foundry Street – he was the intended victim:

“The ball went out into Foundry Street and two or three of us went after it. We saw stones coming down. The other side maybe thought we were running out to make a charge. Some of my crowd replied. I saw the prisoner running from the direction of Clonallon Street to the railway gate. He then ran to the cottages across the road. He suddenly put his right hand upon his left wrist and fired two shots. I ‘duked’ and then heard three more shots. The shots were fired in my direction. I saw the flash of the shots and the smoke both. The prisoner ran away and I later heard that McArdle had been shot.”7

Although the shots were fired at Magee, he was not the one hit. Jane McArdle told the court: “My son Francis was standing outside the door of my house 36 Foundry Street when I heard him shouting ‘I’m shot! I’m shot!’”8

John Smyth was tried for the attempted murder of the boy. Smyth’s mother said he had been at home sick all day. A neighbour also said she had seen him in the house shortly after the shooting.9

He was found not guilty.

Bridget McCormick

Just over two months later and significantly, a month before Smyth appeared in court for the attempted killing of McArdle, there was another shooting which may have been linked to the first incident – it also happened outside McArdle’s house. On the afternoon of 26 June 1921, 16-year-old Bridget McCormick was standing at the door of that house – she outlined the scene that unfolded in almost slow-motion terms:

“I was standing at the hall of 36 Foundry Street with another girl when I saw two men come from the direction of Harland Street. One was dressed in a grey suit and the other in navy blue. The man in the grey suit crossed the street to the lamppost and he gave a signal to the one in blue. I heard the report of shots from the boy in navy blue. I saw a revolver in his hand. I knew him. He was the prisoner. I have known him since the riots last July. I was struck by a bullet on the arm and on the neck and was stunned and frightened.”10

She described her state of shock after being shot:

“I do not know whether other shots were afterwards fired as my mind was not too clear…Nellie Doyle and Cassie McArdle and Kathleen Carson were with me at the door. The sergeant came to me about five minutes afterwards, we were then in the house. I knew the prisoner’s name. I never thought of telling him the name. I was that much excited I did not want my mother to know for she was just out of an illness.”11

The wounded girl was obviously petrified of potential further consequences – her friend, 13-year-old Nellie Doyle, told the court that when the policeman arrived, “I did not tell him Mawhinney’s name…Bridget McCormick told me not to tell the name.”12

However, a couple of days later, Bridget identified John Mawhinney as the one who had shot her. On this occasion, the man accused was found guilty but as he was only aged 17, he was sentenced to three years in Borstal.13

Adam Young

On the night of 25 June 1921, Adam Young was standing at the door of his house in Isabella Street near North Queen Street. He described how John Nolan came out of his house in Moffet Street, which faced Young’s:

“He pulled a revolver out of his hip pocket and fired one shot at me. He was about four to five yards from me. I got hold of him and struggled with him to take the revolver off him. A man named Michael O’Neill then came down and snatched the revolver off the prisoner and ran up the street.”14

According to Young, Nolan had been pursuing a dedicated, if ineffective, vendetta against him for some time:

“Nolan presented a revolver at me in Little George’s Street about ten days prior to this occurrence…I did not go to the police on that occasion…That was the fifth occasion he presented a revolver at me, he did it first in August last in Isabella Street where I live. In about three days he presented a revolver through my window at me. I went to Henry Street Barracks and saw District Inspector Gerrity about it. The hole is still in the window…The third time was in Little George’s Street at about a quarter past ten in the month of September. I was going home and he fired at me. I did not go to the police. He stepped round the corner and fired in my direction. The fourth occasion I have already described it was on a Saturday night I was about 15 or 20 yards from him.”15

Young’s mother said she had seen Nolan sitting on a chair in his own doorway with a revolver; strangely, she did not even attempt to close her own front door, despite the fact that, “On the night the King was here [22 June 1921] he held out a revolver to me and said ‘How would you like that?’ …I did not complain to the police when Nolan presented the revolver at me.”16

Despite alibi evidence offered on Nolan’s behalf by neighbours and both the son and daughter of O’Neill, Young was probably relieved when Nolan was convicted and sentenced to six months’ hard labour.17

John Bryson

Nineteen-year-old John Bryson lived in Nelson Street in Sailortown and worked in the shipyard as a heater boy. On the morning of 14 July 1921, there was a sound of an explosion nearby , so he went looking for his younger brother:

“When I got as far as the corner of Dock Street and Nelson Street I stopped to look round for my brother. While I was standing there I saw Francis Ferron along with four other persons who I do not know, they were at the foot of Dock Street, in Garmoyle Street. They all had revolvers in their hands and they were firing. I saw Ferron separate from the others and go over towards the bonded stores at the foot of Dock Street. I saw him plainly, he was on the same side of the street as me. I saw him lift his hand and point his revolver in my direction. He fired and I felt something strike me on the right hip. I fell to the ground and fainted. I remember nothing until I was in the hospital. I have no doubt that it was the defendant who shot me.”18

The reason why Bryson was so sure about his attacker’s identity was that Ferron lived in the house opposite his. He had had a lucky escape: “I had a half crown in my hip pocket and I believe the bullet struck the coin. I paid my tram fare with the half crown when coming from the hospital.”19

Nelson Street, where John Bryson and Francis Ferron lived opposite each other

Ferron’s mother said he was in the house at the time of the explosion: “She heard Mrs Bryson shouting across the street that her (witness’s) Fenian son would be gone for that night.” A neighbour testified that she had seen Ferron at home when the explosion occurred.20

He was found not guilty.

Jane Theresa O’Reilly

At 8:20 on the morning of 31 August 1921, Jane Theresa O’Reilly, aged 16, was going to her place of work in Little York Street; she was accompanied part of the way by her mother – they parted at the corner of Great Patrick Street, with her mother watching her as she went.

The teenager recalled:

“I heard a shot being fired. I put out my hand to lift my shawl and I then heard a second shot and I felt myself being struck on the left arm. My arm dropped and became damaged. I ran a short distance and fell to the ground. At the time I heard the shots I saw Henry Murdock standing at the corner of Maguire’s Church in Little York Street. He had a long thing like a rifle pointed towards me and I saw a blaze from it at the time I was struck on the arm. I also saw another man named Oliver White at Reagan’s corner in Great George’s Street, he had a rifle in his hand.”21

She said she had known both men for two years, as they lived near her. Her mother said that she “heard three shots and immediately heard my daughter give a loud scream and saw her run a short distance towards Great Patrick Street where she fell.”22

(L) Jane Theresa O’Reilly (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 10 September 1921); (R) Little York Street, where she was shot (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Hogg Collection)

Murdock and White were charged with the attempted murder of the girl. A neighbour said she had seen Murdock in his own house at the time in question and a friend said Murdock had stayed at home all day with his wife who was sick. White’s foreman said he had been at work from 7:45am until 6 o’clock in the evening.23

Both men were acquitted.

John Walsh

On the afternoon of 2 September 1921, John Walsh, aged 15, was walking down Wall Street in Carrick Hill:

“Something struck me on the jaw causing a wound. I heard revolver shots fired and saw a crowd standing at the corner of Cavour Street and Wall Street. I went and had the wound dressed by Dr McNabb. I saw the prisoner in the crowd I have mentioned with a black revolver in his hand.”24

Shortly before being shot, he had seen his attacker, who had previously lived on the same street as him, nearby: “I had seen Topping at the top of Unity Street about ten minutes before I was hit. He had the black revolver in his hand. He shook the revolver in the air and shouted something which I did not hear.”25

Two neighbours said they saw James Topping fire the shot; a third neighbour, Emma Bradley, ran to bring her child in from the street and claimed that Topping had shouted, “Where are the IRA, send out the gunmen.”26

In court, Dora Davis, a shopkeeper in Hanover Street where Topping was now living, testified that he had been in her shop at the time of the shooting; her evidence was corroborated by another resident of Hanover Street.27

Topping was found not guilty.

Daniel McCambridge

It was well-known in Belfast that the licenced trade was dominated by Catholics – this made owners and barmen potential targets in the eyes of would-be sectarian killers. Beginning in late November 1921, a series of Catholics working in the trade were shot dead: on 21 November, James Hagan was killed in the bar in which he worked in Station Street in Ballymacarrett; the following night, Patrick Malone was killed in his spirit grocery on the Beersbridge Road, also in Ballymacarrett, while on the same night in the north of the city, Patrick Connolly was killed in his spirit grocery in Duncairn Gardens; two days later, John Kelly was killed in his spirit grocery on the Crumlin Road.28

A spirit grocery, looted and burned in the initial outbreak of violence (Illustrated London News, 4 September 1920)

The case of Daniel McCambridge is particularly noteworthy because when Charles Stewart was charged with his attempted murder, members of the IRA appeared in court as witnesses for both the prosecution and the defence.

On Christmas Eve 1921, McCambridge was working as a barman in Kirkpatrick’s spirit grocery in Herbert Street in Ardoyne. The premises were closed but at around 9:30pm, there was a knock on the door and four men entered.

Three of the men ordered a round of ports, then another round; but when they ordered a third round, McCambridge refused to serve them and instead opened the door to let them out:

“One of them pulled out a revolver and said, ‘You f—-r we have you now.’ I went outside. I heard them coming after me. I ran down the street and a shot was fired after me. I wasn’t hurt. I looked round when I was running down the street and prisoner was first of three people who were following me. He was the man who had the revolver.”29

Charles Stewart was arrested by Constable Michael Furlong of Leopold Street Barracks, one of the nationalist policemen who, in March 1922, provided a statement about the activities of District Inspector John Nixon to a Free State investigator.30

Stewart was identified in the barracks as McCambridge’s attacker by the fourth man who had entered the bar, William McCorry. Given that the IRA had a policy of not recognising British courts, McCorry’s initial response when cross-examined by Stewart’s barrister was one not often heard from prosecution witnesses in Belfast courtrooms: “I am a member of the Irish Republican Army.” He said he did not know the other three men, but ran out after them and managed to catch Stewart by the coat before he fired the shot at McCambridge.31

When the case came to trial, evidence for the defence was provided by Joseph Murray, who did not announce to the court that he was the commander of the 3rd Battalion of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade and thus McCorry’s commanding officer; he simply stated that, “he had known the prisoner for eighteen months, and had he been at the spirit grocery on the night in question he would have recognised him.” Stewart was found not guilty, largely on the strength of an alibi provided by Martha Burgess, who said they had been at a cinema together from 7:30pm until 11 o’clock.32

Despite his startling admission in court, McCorry was not arrested and interned until November 1922. Neither he nor Murray mentioned the incident or their conflicting roles in it in their applications for Military Service Pensions.33

Patrick McMahon

Like McCambridge, Patrick McMahon also worked in a spirit grocery, but it was one that he owned at 215 York Street. At 6:40pm on 24 November, he was held up and robbed by two armed men. About ten minutes later, he closed the front door of the premises:

“I then went to close the side door. I heard a footstep outside. I opened the door and looked out. I saw a man with a revolver standing just outside the door. He did not say anything. He fired three shots at me. There are two glass panels in the door. Three shots came through the door. I stooped down and the shots went over my head. When I went to push the door to, the prisoner fired the shots through the glass. I had a good view of the man. The gas was lit in the kitchen and the light flashed in his face when I opened the door.”34

York Street (© National Library of Ireland, Lawrence Collection)

David Duncan was charged with the attempted murder of McMahon, but he was subsequently charged with the murder of James McIvor, another spirit grocer in nearby Little Patrick Street who was killed the morning after the attack on McMahon. The trial for the second, more serious charge, was heard first.

Duncan was identified by two eyewitnesses as being the man who had killed McIvor, but their character was questioned both by both Duncan’s defence barrister and the trial judge in his summing up. Duncan was described as being an adjutant in the Ulster Imperial Guards, a loyalist paramilitary organisation, although “Constable W.J. Robb deposed to the prisoner calling men of the Imperial Guards to protect a house occupied by a Roman Catholic.” Several witnesses provided alibi evidence on Duncan’s behalf. Having considered the evidence for all of eight minutes, the jury found Duncan not guilty.35

After this verdict was returned, a nolle prosequi was entered in relation to the attempted murder of McMahon – the charges were dropped.

John and Michael McMahon

Almost exactly four months after the attempted killing of McMahon, two of his nephews had narrow escapes in the single most notorious incident of the entire conflict. But John and Michael McMahon very likely had to contend with survivors’ guilt in the aftermath of the attack on their family home on the night of 23/24 March 1922, in which their father Owen, their four brothers and the family lodger Edward McKinney were all killed.

The facts of the McMahon family killings are well-known. While John afterwards spoke to reporters from his hospital bed, both he and Michael also made statements to police who arrived to investigate the attack.

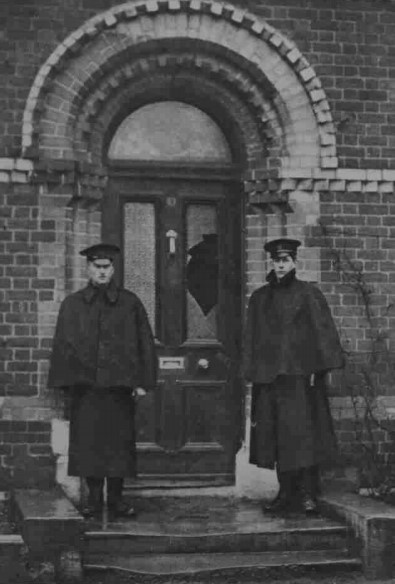

Police guarding the McMahon family home the morning after the attack (Illustrated London News, 1 April 1922)

John described the carnage to the police:

“[Spelling and punctuation as per original document] I was sleeping in the room on the second floor with Gerard and Michael, I heard the sound of glass breaking. and I got up and looked down stairs. I saw a weak light on the ground floor outside the dining room door. My mother and father were coming down the stairs at this time and a stranger in mufti came up and said ‘Get down below’ he asked ‘Is there anybody in the top rooms’ He went up and brought down Bernard and Eddie McKinney from the top room. We all came down undressed. There was a man in police uniform at the drawing room door, I spoke to him and said I had a brother undergoing an operation He said ‘It is allright it is onlya raid’ I went down to the dining room and finally there was collected in that room MY father. Bernard (26). Frank (24).Patrick 22) Myself. Gerard. 15 years, Michael 12 years. and Edward McKinney.

Ther was a man there with a dust coat a trench coat with a belt on it. he said ‘Do you boys say prayers’. He shot straight before him at my father. Another man who was in uniform shot in my direction I ducked my head and was shot in the neck I fell on the floor under the floor under the table and lay there.

There were two or three shots more fired and then they went out. I thought one filled his revolver but I am not sure.

Inside the door on the left lay Frank. in the centre of the hearth rug were my father, Eddie McKinney and Gerard, Bernard lay near me. I waited till they went and then got up and took a drop of brandy and went upstairs. There were 5 men in all in the attack. The one with the dust coat seemed to be the leader. he was clean shaven. well made, about 30-35 years. There was a much taller man in uniform who did the shooting, he was the only one in uniform I saw shooting. He had dark complexion. and was about 6 feet. One had an English accent.”36

John McMahon, pictured in hospital after being shot (Freemans Journal, 28 March 1922)

Although press reports said that the three females in the house – Eliza McMahon, her daughter Lillie and niece Catherine Downey – were all held in an upstairs room, Michael told the police that his mother had also come downstairs:

“[Spelling and punctuation as per original document] I was in bed with John and Gerard on 23.24. 3.22. on third floor. I heard the glass breaking in the door and then I saw my father standing at our door, a man came into my room and ordered us down stairs. we were dressed in our night dress the man said ‘Come on. Come on’. When i w3nt down stairs I went into the dining room I saw three men o the stairs in the dark they had policemans coats on them. We were all collectd in the dining room, my father. Bernard, John, Patrick. Frank, Gerard. Eddie McKinney and myself. My mother was coming downstairs and man in the fawn coat said ‘go you back to your bed’. My mother said ‘I am going to go on down too’ She then entered the drawing room The man in the fawn coat said when we were collected ‘Did you ever say your prayers’

He then fired, When I saw him lift his revolver I fell under the table and began to moan and pretend to be shot. There was a number of other shots but I dont know who fired them, the result was that all the others were killed or wounded. I saw John lying near me.”37

Eliza McMahon also made a statement to the police:

“[Spelling and punctuation as per original document] I heard a breaking of glass and I thought it was a bomb

My husband and I got up and ran downstairs from the third floor. I met a man on the stairs, he was in police uniform he had a revolver in his hand and he ordered me to return to my bed. The other occupants of the house were coming out of their rooms with other men in uniform bringing them out saying ‘get downstairs’ ‘come on’ ‘Come on’. I said ‘What do you want with them’ my husband said they are only raiding the house

I said ‘What are you going to do with them’ the man replied ‘Go back’ ‘Go back’ I went into the drawing room and raised the window I heard the shots in the dining room where my husband and family had been brought I opened the window and shouted ‘Murder’ ‘Murder’ I saw two fellows clearing off into Bruces Demesne I saw 4. or 5 men in uniform and another who wore a trench coat in the house.”38

John and Michael’s cousin, Mary Downey, had been staying in the house; she gave the police a description of the killers’ leader:

“[Spelling and punctuation as per original document] I was in bed in a room on the first floor landing with Lillie, I was awakened by a light flashing in my eyes. I saw a man dressed in a light trench coat with belt and light coloured cap He had a round soft looking face and very black eyes, he was about 5 ft 9 in in height. He did not speak but left the room I got up, he was talking to my aunt on the landing, at thes ame time I saw three men going up the next flight of stairs they wore black waterproof coats the same as worn by the police and policeman’s caps. I went back into the bedroom and I heard perwons coming down the stairs, I heard my uncles voice saying ‘What are you going to do’. and a voice replied ‘GEt on Down’. The next thing I heard a number of shots about 12 in number.”39

The Royal Irish Constabulary City Commissioner, John Gelston, asked the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates, to convene a coroner’s inquest without a jury, as “Owing to the disturbed state of the city, jurymen are placed in a difficult position in dealing with such cases.” Bates prohibited the holding of an inquest and instead, acting under the recently-passed Special Powers Act, directed the City Coroner to hold an inquiry. This was not held until 11 August – the verdict returned in all cases was that each of the victims “came to his death from gunshot wounds…wilfully inflicted by some member or members of an unlawful assembly.” As the Belfast newspapers were on strike at the time, these verdicts were not reported in the press.40

No-one was ever charged with the McMahon family killings or the attempted killings of John and Michael. However, in Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles (reviewed here), Edward Burke has identified David Duncan, previously charged with the attempted murder of Patrick McMahon, as being the most likely suspect for the man in the trench coat who led the attack on the McMahon family home.41

William Watson

In the spring and summer of 1922, Catholics living in relative isolation in parts of east Belfast off the Ravenhill, Woodstock and Castlereagh Roads, who had until then largely escaped the worst of the sectarian violence in the city, began to be attacked by loyalists. Three men were killed, while families were evicted and their possessions burned.42

William Watson was a Presbyterian, originally from Scotland. His wife Rachel was a Catholic and their three daughters and two sons were all raised as Catholics – it may have been the latter fact that led to the family being targeted.43

Bloomfield Road, off Beersbridge Road. The Watson family lived in Bramcote Street, a side-street to the right just beyond the tram in the distance (© Old Belfast Facebook Group)

On the evening of 10 July, Watson answered a knock at the front door of the family home in Bramcote Street, near the Beersbridge Road:

“I opened the door slightly. At once there were two revolvers pointed at me. I endeavoured to push the door shut against the men but they were too powerful for me. Then they got in on top of me. There were two men. They each had a revolver and said they came to search the house. I told them that there was no person in the house or words to that effect. And that they were not going to get in.”44

Alarmed that his family was suddenly in mortal danger, Watson began a desperate hand-to-hand struggle with the intruders:

“I caught the wrists that held the revolvers and twisted them round and held them. The men struggled with me and tried to push me inside the house. I held on to their wrists. They pushed me to the foot of the stairs. I got up on the second step and still held the revolvers up. One of them managed to turn the revolver around to my left shoulder. He fired and the bullet grazed my skin. It went right through my clothes. We continued struggling until there was another shot fired which struck the roof. By this time I had managed to get the hold of the revolvers by the breech and still kept them turned from me. I managed to push the two men out to the front gate. I got them on the outside of the gate. I was inside.”45

Rachel Watson saw her husband battling with the men and ran from the back door, screaming for help. At that point, Watson’s neighbour, Henry Little, having heard the commotion, came to his assistance:

“The man whom I was holding with my right hand got free and the man I was holding with my left told him to brain me. The man who had got free fired at me point blank. The bullet missed me. I heard a man fall behind me and I saw the blood oozing between my leg. I subsequently ascertained that the man who was shot was Henry Little. The man I was holding must have got away because I have no recollection of what occurred after the shot was fired.”46

The following morning, at an identity parade held in Strandtown police barracks, Watson picked out Thomas Bowers as resembling the man who had fired the shot that killed Little. His wife said Bowers was one of the men with whom she had been her husband struggling and that he was the man she had seen running away with a revolver when she returned to the house a few minutes later: “I had no hesitation in pointing him out.”47

However, when the case came to trial, neither of the Watsons would swear definitively that Bowers was one of the two men who had been at their home. Presented with this sliver of doubt, the judge said, “It would only be a waste of public time to go further with the case. He directed the jury to find a verdict of not guilty.”48

Summary

A number of common features can be seen in the stories of these thirteen survivors.

The first is that some of the incidents were linked to earlier ones: the fact that Patrick McGurnaghan gave evidence in the trial of the man accused of shooting Sarah Bannon; the fact that the shootings of Francis McArdle and Bridget McCormick happened outside the same house, before the trial for the first shooting began; the very obvious connection between the attempted killing of Patrick McMahon and the actual killing of his brother and nephews.

These cases show a common urge to either intimidate witnesses from testifying or to punish those who had already done so – clearly attempts to deter potential witnesses in future trials.

The young age of many of those shot is also notable – several were still in their teens. On one hand, this – and the fact that three of these survivors were female – demonstrates the extent to which lethal violence was directed at non-combatants. But it also begs a question: where were the adult survivors who constituted the vast majority of those wounded? For some reason, the teenagers seem to have been less cowed in terms of coming forward to provide evidence.

Most of the attacks – apart from the McMahon family killings – took place in areas like Ballymacarrett and North Queen Street-York Street, where sectarian boundaries were often scrambled, sometimes consisting of no more than Catholics and Protestants living at opposite ends of the same street; John Bryson and Francis Ferron even lived directly across the street from each other.

This involvement of close neighbours increased the chances of an intended victim recognising the person shooting at them as being someone they had frequently passed in the street.

But despite the apparent strong foundation for such eyewitness testimony, often supported by that of other neighbours from the same street – and even allowing for their testimony being clouded by bitter, long-standing sectarian animosities – it is striking how often the word of eyewitnesses was trumped by alibi evidence, with the latter usually being sufficient to secure an acquittal. Neither the court nor newspaper records offer any indications of how rigorously those alibis were challenged at trial – if at all.

But almost invariably, more weight was attached to the alibi than to the recollection of the person who said they knew who was shooting at them. What that meant was that only two of these cases led to the would-be killer being found guilty and given a custodial sentence.

In the remainder, the intended victims, having recovered from their wounds and shown the courage to identify their would-be killers in court, were left to carry on with their lives as best they could in such a highly-charged context, knowing that the person who tried to kill them was still at large.

References

1 Deposition of Sarah Bannon, 2 August 1921, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Thomas Saunders – shooting at Sarah Bannon, BELF/1/1/2/67/19.

2 Belfast News-Letter, 27 February 1922.

3 Deposition of Patrick McGurnaghan, 19 January 1922, PRONI, James Galbraith – shooting at Patrick McCunningham [sic], BELF/1/1/2/67/21.

4 Depositions of Mary McGurnaghan & Minnie Parks, 6 December 1921, ibid; Deposition of Minnie Parks, 9 August 1921, PRONI, Thomas Saunders – shooting at Sarah Bannon, BELF/1/1/2/67/19.

5 Belfast Telegraph, 21 February 1922; Intelligence Officer, Fianna Belfast to Intelligence Officer, Belfast Brigade, IRA, 17 March 1922, PRONI, Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, HA/32/1/130.

6 Deposition of Jane McArdle, 8 April 1921, PRONI, BELF/1/1/2/65/9 John Smith – shooting at Francis McArdle.

7 Deposition of Patrick Magee, 8 April 1921, ibid.

8 Deposition of Jane McArdle, 8 April 1921, ibid.

9 Belfast News-Letter, 29 July 1921. The court records give his surname as Smith but he signed his bail recognizance form as Smyth, the spelling also used in the newspaper reports.

10 Deposition of Bridget McCormack, 30 June 1921, PRONI, John Mawhinney – shooting at Bridget McCormack, BELF/1/1/2/65/11. The court records give her surname as McCormack but she signed her deposition as McCormick, which was the actual family name.

11 Ibid.

12 Deposition of Nellie Doyle, 30 June 1921, ibid.

13 Deposition of Bridget McCormack, 30 June 1921, ibid; Witness, 5 August 1921.

14 Deposition of Adam Young, 7 July 1921, PRONI, John Nolan – shooting at Adam Young, BELF/1/1/2/65/13.

15 Ibid.

16 Deposition of Agnes Young, 7 July 1921, ibid.

17 Belfast News-Letter, 30 July & 1 August 1921.

18 Information form of John Bryson, 14 July 1921, PRONI, Francis Ferran [sic] – shooting at John Bryson, BELF/1/1/2/66/10.

19 Ibid.

20 Belfast News-Letter, 13 December 1921.

21 Information form of Jane Theresa O’Reilly, 28 September 1921, PRONI, Oliver White and Henry Murdock – shooting at James and Theresa [sic – Jane Theresa] O’Reilly, BELF/1/12/67/22.

22 Information form of Susanna O’Reilly, 28 September 1921, ibid.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 16 February 1922.

24 Deposition of John Walsh, 9 September 1921, PRONI, James Topping – shooting at John Walsh, BELF/1/1/2/66/13.

25 Ibid.

26 Depositions of Victor Morrissey, 9 September 1921, and of William Doran & Emma Bradley, both 20 September 1921, ibid.

27 Northern Whig, 9 December 1921.

28 For details of inquest reports relating to these killings, see (Hagan) Belfast News-Letter, 12 January 1922, (Malone, Connolly & Kelly) Belfast News-Letter, 7 January 1922.

29 Deposition of Daniel McCambridge, 31 January 1922, PRONI, Charles Stewart – shooting at Daniel McCambridge, BELF/1/1/2/67/20.

30 Deposition of Constable Michael Furlong, ibid; Statement of Constable Furlong, Leopold Street Barracks, 22 March 1922, National Archives of Ireland, D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland outrages, TSCH/3/S11195.

31 Depositions of William McCorry, 24 & 31 January 1922, PRONI, Charles Stewart – shooting at Daniel McCambridge, BELF/1/1/2/67/20.

32 Northern Whig, 24 February 1922.

33 Military Archives, Military Service Pensions Collection, MSP34REF59068 William McCorry & 24SP12713 Joseph Murray.

34 Deposition of Patrick McMahon, 5 January 1922, PRONI, David Duncan – shooting at Patrick McMahon and murdering James McIvor, BELF/1/1/2/67/8.

35 Depositions of Bernard Monaghan, 17 January 1922 & Daniel Loughran, 27 January 1922, ibid; Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 4 March 1922.

36 Statement of John McMahon, 24 March 1922, PRONI, Murder of Owen McMahon and family, and Edward McKinney, HA/5/193.

37 Statement of Michael McMahon, 24 March 1922, ibid.

38 Statement of Eliza McMahon, 24 March 1922, ibid.

39 Statement of Mary Catherine Downey, 24 March 1922, ibid. Contradicting the press reports that all three females in the house had been gathered together, both she and her cousin Lillie confirmed that they were left in the bedroom where they had been sleeping – see Statement of Lillie McMahon, 24 March 1922, ibid.

40 City Commissioner to Minister of Home Affairs, 10 April 1922; Ministerial Orders, 12 April 1922; Copy of verdicts, Inquest on the McMahon Family, Coroner’s Court, n.d., ibid.

41 Edward Burke, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles, (Newbridge, Irish Academic Press, 2024).

42 See, for example, entries dated 19, 20, 21, 22 & 28 April and 3, 5 & 9 May 1922 in National Library of Ireland, Art Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee, Ms 8,457/12. The three men killed were James Rice (Ravenscroft Avenue, 14 February), Charles McMullan (Sherwood Street, 15 February) and William Millar (Willowfield Street, 21 June).

43 https://nationalarchives.ie/collections/search-the-census/view-pdf/?doc=nai002198878

44 Deposition of Henry Watson, 12 July 1922, PRONI, Thomas Bowers – murder of Henry Little and shooting at William Watson, BELF/1/1/2/69/7.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Depositions of Henry & Rachel Watson, 12 July 1922, ibid.

48 Belfast News-Letter, 25 November 1922.

Leave a comment