The first part of this post reviewed the activities of the revived UVF and of the newly-formed Ulster Brotherhood, or “Crawford’s Tigers,” and Ulster Imperial Guards. This part looks at the Cromwell Clubs and the Ulster Protestant Association.

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes

The Cromwell Clubs

Among the fifteen witness statements given by Belfast republican veterans to the Bureau of Military History, there was not a single mention of “Cromwell Clubs.” Nor does the phrase figure among the Military Service Pensions Collection files released to date of members of the Belfast IRA, Cumann na mBan and Fianna. They could reasonably be expected to have known who they were fighting against.

The very existence of the Cromwell Clubs is extremely questionable and hinges on a single report by a Nationalist Party alderman on Belfast Corporation, John Harkin, who shared his information with both Sinn Féin and the IRA.

Harkin’s handwritten memo was forwarded by the Belfast-born TD, Seán MacEntee, to Éamon de Valera: “Formed as Auxiliary to Unionist Clubs. Operations directed from Old Town Hall…A minimum of 50 men and 5 officers to each ‘Cromwell’… Sergt McCartney (RIC [Royal Irish Constabulary]) Musgrave St Barracks appears to be the principal organiser.”1

Claiming that military intelligence had supplied the group with lists of prominent republicans and Catholic citizens and businesses, Harkin went on to describe its aims, as outlined by Sergeant McCartney at a meeting in Brougham Street Unionist Club off York Street:

“The shootings of prominent republicans and Catholic citizens, burnings of business premises, ambushing and shootings in crowded city streets. Midnight raids on country houses and the establishment of a reign of terror ordered by these Clubs in the ‘Six County’ area and the subjection of those who are refusing to recognise the ‘Ulster’ Parliament.”2

Along with his memo, Harkin also shared clippings from the Belfast Telegraph with MacEntee, which included a photo of what he described as a parade of the “North East Club.” However, Harkin was incorrect, as the photo was of a parade of the Ulster Imperial Guards.

Frank Crummey, the Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, had clearly also seen Harkin’s memo. Crummey sent a report, essentially paraphrasing Harkin’s, to Michael Collins, adding that his information was that the group had been in existence for about a month.3

This would roughly coincide with the foundation of the Imperial Guards, whose establishment had first been mooted at the end of the previous July. However, the Imperial Guards had their head office at 5 Bedford Street, which would rule them out as being the group to which Harkin was referring. In addition, as seen in part 1 of this post, their leading officers were ex-servicemen, not serving policemen.4

The references to the Old Town Hall in Victoria Street, the address at which both the Ulster Unionist Council and the UVF were based, as well as being where Fred Crawford held organising meetings for his “Crawford’s Tigers” group, would seem to indicate that “Cromwell Clubs” was a garbled reference to the Tigers. IRA intelligence on loyalist paramilitaries was never perfect.

The Order of Buffaloes

On the broader theme of loyalist paramilitaries named after animals, at times IRA intelligence could be laughably misinformed.

In 1924, the former Intelligence Officer of the Belfast Brigade, David McGuinness, by then serving in the Defence Forces in the south, noted in a report that, “The Order of Buffaloes, like the Protestant Defence Association, is composed principally of ‘A’ and ‘B’ Class Specials and can be used by them to support them when needed (vide part played by Buffaloes in Belfast during Pogrom).”5

In reality, this group was the Belfast chapter of an English charitable society established in the 1820s, revelling in the full title, the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes. It was founded by stage hands and other technicians working in theatres.6

The Belfast branch held their first church parade on 18 December 1921, when “close to 1,000 of the brethren assembled at the City Hall and, headed by the Willowfield Brass and Nelson Flute Bands, marched to the Trinity College Mission, Shankill Road.” This was the diametric opposite of the usual direction of travel for political or paramilitary parades, which marched to, not from, City Hall.7

The main activity of the Buffaloes was not sectarian violence, but fund-raising for their mission fund: they were benevolent rather than malevolent. In April 1922, “A most successful and enjoyable social and ball took place in the Cafe Royal, Wellington Place, when a large and representative attendance of the members of the Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes…sat down to an excellent knife-and-fork tea.”8

The Ulster Protestant Association: Shankill Road

While the Order of Buffaloes was harmless, the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA) was anything but.

According to Austen Morgan, “an organisation of this name was in evidence from the autumn [of 1920], with branches in Ormeau, Shankill Road, York Street and Ballymacarrett. It was set up, according to later police intelligence, ‘following on the disturbances which…began in the city.’”9

It was initially based in the shipyards: “The UPA was reported on 19 August as having suggested vetting committees in each shop, the idea being to maintain loyalist integrity among the workforce.” In these can be seen the genesis of the “vigilance committees” which mushroomed in the immediate aftermath of the workplace expulsions.10

By the second half of 1922, District Inspector (DI) Reginald Spears of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) E District in east Belfast believed that “The Ballymacarrett branch of the UPA is the only active branch in the city.”11

In this, he was mistaken.

John Williamson, a dock labourer from Fortingale Street in the lower Shankill, was perhaps not the brightest crayon in the box. With previous convictions for stabbing a policeman and rioting, he was awaiting trial on charges of unlawful possession of two rifles when, according to an RUC report, he killed two children in a bomb attack on their family home in Brown Street, off Millfield, on 31 March 1922. The family’s surname may have led the killers to believe that they were attacking Catholics, but Joseph and Francis Donnelly, aged 12 and 2 respectively, were members of a Church of Ireland family.12

Brown Street, where the Protestant Donnelly children were killed in a bomb attack on their home (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Hogg Collection)

Having previously stabbed a police constable was no barrier to Williamson enrolling as a C1 Special. This in turn allowed him to escape conviction on the firearms charge – he claimed that the C1s were told they could keep a rifle and revolver at home for personal protection. However, he was arrested again in November 1922, having intimidated his neighbours: “his co-religionists in the locality where he resided were delighted when they heard he was interned.”13

While interned, Williamson appeared before the Advisory Committee which evaluated applications for release. He somehow thought that it would help his cause when he told them: “The UPA exists to protect property…I was an organiser of the branch. All the members of the UPA are gunmen. I was a gunman and I suppose the police thought they were in danger. All the members of the UPA had arms which were given out by the UPA.”14

Even the notorious DI John Nixon, whose C District covered the Shankill, felt that “in the interest of peace it was well to have him out of the way.” Williamson reacted badly to his appeal being rejected – he assaulted a prison warder, and was sentenced to four months’ hard labour.15

He was eventually released in June 1923 but quickly returned to form and threatened to shoot two police constables the following month. While awaiting trial on this charge, he offered to emigrate to Canada – the authorities felt no urge to stand in his way.16

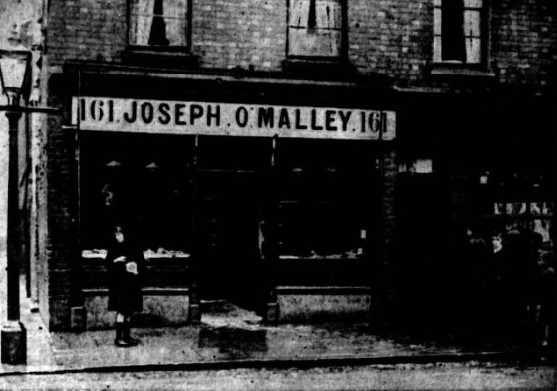

The police suspected that Williamson’s accomplice in the killing of the Donnelly children was George Scott, a shipyard worker from Downing Street, also in the Shankill. They also believed that Scott had shot two barmen on the Oldpark Road and “was the principal ring leader of a gang of ruffians who burned and wrecked many public houses and spirit groceries in the Shankill Road area.”17

B Specials: George Scott was a member who was suspected by the police of involvement in the killing of the Donnelly children (© Police Museum, Belfast)

Scott was one of three uniformed B Specials arrested on firearms charges at 2:15am on 13 August 1922 on the Grosvenor Road, two hours after they had come off duty – police heard shooting from Distillery Street and when they went to investigate, there was no-one around other than the three Specials. Scott was dismissed from the force the following day and interned in October. In November, all three Specials pleaded guilty to having the weapons for unlawful purposes – Herbert Armstrong and David Brown were bound over to keep the peace, but Scott was returned to internment, where he remained until June 1923.18

Although not explicitly named, the Shankill Road UPA were also very likely to have been the “loyalists from the Shankill Road” who volunteered their dubious services further afield in Belfast. At Christmas 1921, a group of Catholic refugees evicted from their homes in Ballymacarrett began squatting in buildings in May Street in the Market. The manager of the properties appealed to the police to evict them, but they had no legal basis for doing so without a court order which had to be applied for by the estate agent in question. He was unwilling to adopt that approach and instead explored other options: “Shortly after forcible possession was taken a force of 200 loyalists offered to clear these premises.” The Ministry of Home Affairs pointed out that if he took up their offer, then in the almost inevitable event of violence ensuing, the property manager would be equally guilty of unlawful assembly and riot. The refugees remained in the May Street properties until 1924.19

The UPA: Ballymacarrett

While DI Spears was wrong to think that the Ballymacarrett branch of the UPA was the only active one, it was the one against which the police had the most success – he was instrumental in bringing an end to the group’s activities.

He got his first break when he recruited a new informer: “In March 1922, a member of the UPA who had been detailed to commit certain outrages, declined to do so. Instead he conveyed to the Home Office certain information as to the location of arms and ammunition.”20

The Ballymacarrett UPA met in the upstairs room of a pub near St Patrick’s church on the Newtownards Road (© National Museum of Northern Ireland, Green Collection)

Acting on this information, DI Spears led a raid by police and military on a disused stable at 20 Clonallon Street on 26 March, where they found six rifles, ammunition and a variety of other military equipment. William Fitzsimons, who lived at number 18 and whose yard had a hole allowing access to number 20, William Gregg who lived next door to Fitzsimons, and Robert Waddell who lived across the street were arrested. However, when their case was tried in court, they received a bizarre acquittal: “The jury returned with a verdict that prisoners ‘were guilty of knowing the stuff was there, but not guilty of having it under their control.’”21

DI Spears was already familiar with Gregg – the previous autumn, he had prosecuted him for the attempted murder of James Sharpe on 24 September 1921. Sharpe said Gregg had fired two revolver shots at him in Saul Street near the Newtownards Road, wounding him in the thigh; Sharpe’s sister, who lived in that street, claimed she heard Gregg shouting “We’ve got one of them!” as he ran off towards the Newtownards Road. However, Gregg insisted he had been in work at the time of the shooting and was acquitted.22

DI Spears had more success the morning after the Clonallon Street raid when he searched the home of Robert Simpson on Beersbridge Road and found ammunition in his coat pocket and more in a packet which Simpson’s mother attempted to throw in the coal hole – Simpson was sentenced to 11 months’ hard labour. According to DI Spears, “He threatened to murder me for arresting him.”23

This was a significant breakthrough, as Simpson was the chairman of the Ballymacarrett UPA. His mother lodged a petition seeking clemency from the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates; as an indication of the political support which the UPA enjoyed, her petition was signed by the Lord Mayor of Belfast and no fewer than nine Unionist Party MPs. But after a civil service memo indicated that “[the] prisoner has shot no less than fourteen persons since the beginning of the disturbances,” Bates rejected the petition.24

Reacting to the rebuff, Robert Craig, Simpson’s replacement as chairman of the Ballymacarrett UPA, wrote to Bates, threatening to “have a mass meeting of the four branches and to form together and to march to Stormont Castle headed by two bands and to state the case of Robert Simpson.” Stormont Castle was the residence of James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, so this was a pointed threat. However, the planned demonstration did not materialise; all that happened was that Robert Craig announced his new standing within the UPA.25

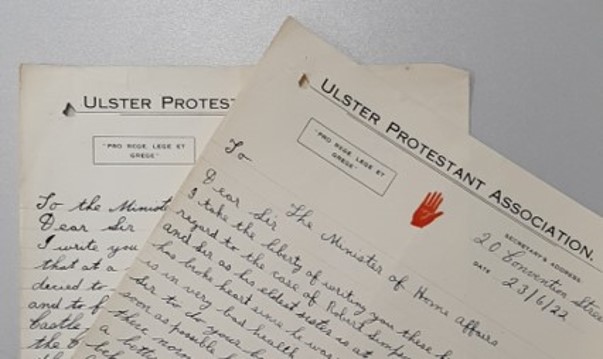

The UPA threatened to march on James Craig’s home if their chairman was not released (© PRONI, Internment of Robert Simpson, Beersbridge Road, Belfast, HA/5/962B; image reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

A month before his sentence was due to expire, Simpson was described as “The most dangerous gunman and murderer in Ballymacarrett” by DI Spears, who stressed that “it is essential that this miscreant be interned.”26

Five months after being interned, Simpson remained an intransigent bigot, telling the Advisory Committee, “I may have used the gun but I always did it for the benefit of Ulster…I shall always hate Roman Catholics.” He was interned until April 1924.27

Simpson may have been DI Spears’ first UPA scalp, but he was determined to have more. However, it was not until the autumn of 1922 that he began making more inroads into the UPA. Two killings in particular prompted renewed determination on the part of the RUC to break the back of the UPA.

On 1 September, a Catholic postman, George Higgins, was shot dead while making his rounds on the Musgrave Channel Road near the shipyards. He was a government employee killed while going about his official duties: this may explain why that same evening, police notices were posted, announcing a £1,000 reward for anyone offering evidence that led to Higgins’ killers being convicted. Incidentally, this was the same amount offered for information that would lead to the conviction of the McMahon family’s killers.

Police notice offering a reward for information leading to the conviction of those who killed George Higgins (© PRONI, Shooting dead of George Higgins, HA/5/26; image reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

Just over a month later, on 5 October, Mary Sherlock left her home in Vulcan Street and went to buy food for her family’s dinner. As she was leaving the Maypole Dairy on the Newtownards Road, a group of men walked up behind her and one of them shot her in the head, killing her instantly.28

That night, the RUC arrested two of the Ballymacarrett UPA, Frederick Pollock and Joseph Arthurs, as well as Alex Robinson from Sailortown – all three were interned on 16 October.

Pollock, his father and one of his brothers were C1 Specials; another brother was an A Special. Despite that, the police believed that Pollock “Was the man who shot dead Samuel Hayes and wounded Thomas Culbert, a Protestant ‘C’ Special in the Britannic Bar on 5th August last, in an endeavour to murder two Roman Catholics…There will be no peace in the locality as long as he is left at large.”29

The RUC also wanted to intern his brother Archibald who they suspected of having been among the group that killed Mary Sherlock, but he fled to England. George Callow, believed to have killed Edward Brennan on the Albertbridge Road on 17 December 1921, was another C1 Special and Ballymacarrett UPA member earmarked for internment but he also evaded capture.30

C1 Specials on the Albertbridge Road; George Callow was a C1 Special who lived on that road and was earmarked for internment

As detailed in a previous blog post, Joseph Arthurs had been tried but acquitted of the shooting and wounding of two British soldiers on the Newtownards Road on 3 June. Despite that verdict, the police believed he was “probably the worst gunman on the Newtownards Road… Was acquitted of this offence owing to the weight of evidence. No doubt he was the right man.”31

Shortly after being interned, Arthurs claimed to have seen the light: “The prison has done me one good turn gentlemen as I have seen my way to God.” On 10 November, he, Pollock and Robinson were deported to England, being barred from returning to Northern Ireland for two years. However, Arthurs came back to Belfast around Christmas only to be re-arrested & once more deported to Liverpool. Returning to Belfast again in April, he fled back to England before the police could recapture him. DI Spears remained unconvinced of Arthurs’ conversion to a more Christian way of life, describing him as “nothing less than a criminal maniac…Arthurs is the lowest type of degenerate human being and quite unsafe to be abroad in any society.”32

Shortly after these initial arrests, DI Spears’ informer “stated that he had been badly treated by the club, and his life threatened…[and] that he would give the police information that would put a stop to further bloodshed.” He gave details of three UPA arms dumps which were raided that evening: at the first, in Solway Street, the rifles had already been moved elsewhere, but at the others, in Susan Street and Pitt Street, the RUC found two rifles, 17 bombs, some rockets and 2,000 rounds of rifle ammunition.33

The aftermath of a loyalist bomb attack in Thompson Street in Ballymacarrett on 18 March 1922: two Catholic women, Annie Mullan and Rose McGreevy, were killed as they slept (Illustrated London News, 25 March 1922)

On 26 October, DI Spears led a police raid on one of the UPA’s regular Thursday meetings in the upstairs room of Hastings’ pub on the Newtownards Road. There were 38 men present out of the total membership of 150; the meeting was being chaired by Robert Craig – he had brought with him the UPA’s books and documents, which DI Spears seized. He had no difficulty in deciphering the “cryptic language” used in them:

“…a revolver was referred to as a ‘dog,’ a rifle as a ‘stick,’ a murder, shooting or bombing as ‘a bit of work,’ etc. When a member was mentioned as having received a ‘grant,’ the issue to him of a firearm was indicated. When a person was visited by an armed gang for purposes of intimidation, it was stated that ‘a deputation waited on so and so.’”34

Ten days after the raid, the Ballymacarrett UPA was effectively decapitated by the arrest and internment of some of its leadership and most active members.

The most prominent of these was the chairman, Robert Craig. DI Spears described him as “the brains of the club,” although he pointed out that Craig was careful not to participate directly in UPA killings, instead directing its operations from a safe distance: “Arranges for the transfer, handing out and taking up of arms. Arranges the various murders and shootings and tells off the various gangs for the work.”35

While there were tensions arising from the rivalry between the UVF and the Imperial Guards, there was clearly no such animosity between the UPA and the Imperial Guards – Craig’s brothers Thomas and William were members of the East Battalion of the Imperial Guards. Both were also members of the C1 Specials, one a sergeant and the other a quartermaster. The latter was one of the C1s entrusted with guarding the remaining weapons from the Larne gunrunning stored at the UVF arms dump in Tamar Street – instead, he “helps him [Robert Craig] in secreting the arms.”36

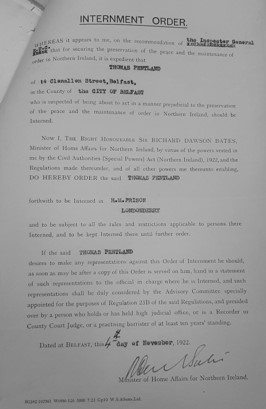

The Ballymacarrett UPA’s vice-chairman, Thomas Pentland, was also interned. While many of the UPA’s members had previous convictions for crimes such as larceny, breaking and entering, being drunk and disorderly, assault and rioting, Pentland’s criminal record stood out in one respect – when aged 15, he had been charged with “having unlawful carnal knowledge of a girl under 13.” However, he was acquitted of this statutory rape.37

More recently, he had been tried for the killing of IRA member Murtagh McAstocker on the Newtownards Road on 24 September 1921. Despite the testimony of three eyewitnesses, Pentland was also acquitted on that occasion.38

Internment order of Thomas Pentland (© PRONI, Pentland, Thomas, Clonallen St, Belfast, HA/5/2221; image reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

Pentland lived three doors up from the Clonallon Street arms dump, but the police had been unable to connect him with that seizure. According to DI Spears, apart from the killing of McAstocker, Pentland made one other notable contribution to the Ballymacarrett UPA, which reveals a particularly sadistic streak:

“He introduced disciplinary measures into the club, and constructed a flogging horse and cat-o’-nine-tails. The flogging horse consisted of a wooden pole supported horizontally by two metal uprights about 3 feet high. Offenders against the rules of the club were brought in, if they were not at the meeting, by armed members told off for the purpose and tried summarily by a nominated jury of the members. On conviction, they were stretched naked across the horse, their arms and legs being fastened to the floor with thongs and were then flogged with the cat, which consisted of a short wooden handle and leather thongs about a foot long.”39

Also arrested and interned at the same time as Craig and Pentland was Robert Waddell, who had been acquitted in relation to the Clonallon Street arms find. According to DI Spears, “At no time was he one of the ‘intelligentsia’ of the club but he was always to the fore in action – shooting and murder.” A fourth UPA member arrested was George Gray, described as “Another of the principal gunmen of the club, as well as being a noted thief and highway robber.” He was identified as being one of a group of UPA members interrupted when preparing to launch a bomb attack on the police in retaliation for the arrests of Pollock and Arthurs.40

The arrests and internment of two more UPA members followed on 18 November – Frederick Brereton and John Darley, both from Dunvegan Street off the Ravenhill Road. The RUC suspected them of being the ringleaders of a group of UPA who had been sniping across the Lagan into the majority-nationalist Market area on the opposite bank of the river; they recovered one of the rifles used in the attacks. Brereton admitted he had been a UPA member but said “I never went out with any shooting parties” – implying that there were others who did. Darley had been spotted by police who intercepted a group of armed men about to launch an attack in Moore Street near the Albert Bridge on 8 September but who had escaped after wounding a policeman.41

There was one other UPA member who DI Spears was keen to capture: he had identified William Morrow as the man who had pulled the trigger when Mary Sherlock was killed. After the raid on the UPA meeting, Morrow fled to Liverpool, where he joined the army. But while he was home on leave in Belfast in January 1923, DI Spears got word that he was going about with a revolver threatening people – on 13 January, the policeman led a raid on Morrow’s home and discovered the revolver and ammunition: “we arrested him after his making a desperate resistance.” On 24 February, Morrow was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment under the Firearms Act.42

The UPA: York Street

Ten days after the internment of Alex Robinson from Andrew Street, near York Street, and just four days after the internment of George Scott from the Shankill, Annie Armstrong, the mother of one of the Specials arrested on the Grosvenor Road at the same time as Scott, wrote to Bates to convey a message from the UPA: “I have received an assurance from the boys of Shankill, Newtownards and York St districts, that there will not be a shot fired, or a bomb thrown, or any other act of intimidation if Scott and Robinson are released.”43

The UPA was clearly rattled by the recent arrests, but her message fell on deaf ears. Another leading UPA figure had already suffered the same fate.

Although he lived in Geoffrey Street in the Shankill, most of William Nesbitt’s UPA activities appear to have taken place elsewhere, as he was “strongly suspected of being a leader of gunmen in the York Street area.” His criminal record included larceny, breaking and entering, indecent behaviour and no fewer than six arrests by the Belfast police for desertion from the Royal Irish Rifles during the Great War.44

A police report outlined their suspicions:

“He delights in taking the lives of Roman Catholics…Suspected of being accountable for the deaths of at least 20 Catholics before his arrest.

On the 17th September 1922 suspected of shooting a man at the junction of Gt Georges St and York St and after doing so walked in company with another man named Alex Robinson…and shot dead James McCloskey, at same time wounding a lad of 15 years.

Suspected of shooting Paddy Lambe a publican in York St in February 1922, and after shooting him helped put him into the ambulance.

Concealed himself in the timber yard a few doors from Henry St barracks about 8am one morning and shot a worker dead.”45

The man shot dead on 17 September was Thomas Costello; Paddy Lambe died from the gunshot wound inflicted on him on 13 February; the worker killed in Henry Street was John Connolly, a Catholic killed on 20 May in retaliation for the IRA’s killing of three Protestant workers in a cooperage in nearby Little Patrick Street the previous day.

Nesbitt had been convicted for possession of a revolver on 19 March, shortly after a shooting in York Street: “I was a C Special but was discharged owing to my bad record.”46

Alex “Buck Alec” Robinson, William Nesbitt’s accomplice in the killing of James McCloskey

He was interned in Derry Gaol on 15 October and inadvertently confirmed his membership of the UPA shortly afterwards when he requested a transfer to Larne Workhouse internment camp to be with his “four ‘comrades’ [who] also wish to go there. They are Robinson, Pollock, Arthurs and Murphy alias Shields.” In a later petition for his release, he complained that of eleven UPA members originally interned, “there is only two of us left in Derry prison.” Both requests were denied.47

By January 1923, still interned in Derry and desperate to ingratiate himself with the authorities, he tried to turn informer:

“The person thrown the bomb in North Queen Street on the night of 29th August 1922 their was a reward out for the person [who]ever could give information who thrown this bomb at a lot of children in North Queen Street I know this man personal his name is McArthur I do not know his sir-name but any who he could be got any time in his house he lives Byron Street of Old Park Road he is well known by the police…Because there was £500 reward out for the person that thrown the bomb so I hope I will get my release soon as possible and to keep my name secret not let it be known to any body.”48

His offer was not accepted.

William Nesbitt told police who had been responsible for the bomb attack on this North Queen Street shop in which eight people were wounded (Belfast Telegraph, 30 August 1922)

In July 1923, a loyalist supporter, coincidentally also named Annie Armstrong, wrote to the Bates, urging Nesbitt’s release. Bates decided to allow him to emigrate to Australia and contacted the Australian High Commissioner in London to see if this could be facilitated. The High Commissioner, perhaps mindful of his country’s reputation as having been largely colonised by convicts in its early years, declined: “…my government have recently issued to this office a strict injunction to exercise great care to prevent the migration of persons who have a blemished record to Australia…Desirable people of good character from Ulster are, of course, welcome to Australia.”49

On 30 August, during another appearance before the Advisory Committee, Nesbitt tried the informer route to freedom again:

“‘I remember Sergt. Bruin being shot. I was on remand in prison at the time. I know who did it. I know it was a man named Glover. I don’t know if any one else was in it. Glover lives in York Road somewhere. If I am left here I will cut my throat.’”50

Unfortunately for Nesbitt, Sergeant Bruin had been killed in April while Glover had been tried for armed robbery two months before that, found guilty and, following a flogging, was now serving a three-year prison sentence. In addition, the police had previously identified Robert Craig from Nile Street off York Street as their chief suspect for the killing of Sergeant Bruin, as well as that of Cecilia Kearns in her York Street shop on 20 May.51

After threatening warders in Derry Gaol that they would be added to a “list” he was compiling for when he got out, Nesbitt resumed writing to Bates, begging to be released. His internment order was finally revoked in May 1924. In July 1935, following renewed sectarian violence in Belfast, he was arrested and once more recommended for internment.52

Summary and conclusions

All the groups of armed loyalists enjoyed political backing from the Unionist Party.

While this was most explicit and pronounced in the case of the UVF, even groups that were at a further remove from the Old Town Hall, such as the Imperial Guards and UPA, could count on the encouragement of hardline Unionist MPs such as William Twadell, William Coote, William Grant and other elected officials, who were keen to be identified as supporters, whether this meant marching in their parades or advocating for the release of interned members.

In one instance, the ties were even familial – Grant was the uncle of the UPA’s Alex Robinson. Grant had also been the adjutant of Crawford’s Tigers until he was elected as an MP. When the son of interned Ballymacarrett UPA chairman Robert Craig died in April 1923, the funeral expenses were paid by Herbert Dixon, Unionist Party Chief Whip and MP for Belfast East.53

It is no surprise that many of the individuals identified as members of the Imperial Guards or UPA were also members of the B or C classes of the Special Constabulary. After all, the Unionist government explicitly sought to strengthen its control over the various loyalist paramilitary groups by incorporating them en masse into the new C1 class of the remobilised Specials after November 1921. In relation to the UVF and Crawford’s Tigers, this seems to have gone largely according to plan.

However, while the government viewed membership of the Specials as an alternative to paramilitary activity, members of the Imperial Guards and UPA clearly saw it in terms of as-well-as, rather than instead-of. To their intended and actual Catholic victims, whether or not their attackers were wearing a C1 armband at the time of the attack was very likely a moot point.

Beyond John Harkin’s report, the Cromwell Clubs do not appear to have had any actual existence as a separate loyalist force. There are no references to them in either the recollections or pension applications of Belfast republican veterans, nor do they appear in the files of the police or the Northern Ireland government. While they have often been mentioned in nationalist accounts in recent decades, this seems to have been on the basis of repeated assertions stemming from Harkin’s misapprehension, rather than any other archival evidence. There were plenty of actual monsters for Belfast Catholics to contend with at the time – there is no need to invent additional bogeymen.

The Tigers were probably the smallest of the four actual paramilitary organisations. Crawford planned for an initial membership of 200 and by his own account, stopped recruiting once he reached this figure in May 1921. They do not appear to have been particularly active.

The revival of the UVF proceeded in fits and starts, first from its initial revival in July 1920 until the formation of the Specials several months later, then resumed between July and November 1921. In terms of numbers, it seems to have reached a maximum of 2,000 members before it was folded into the C1 Specials. Crawford assumed command of the organisation after June 1921 but surprisingly, considering that he was otherwise an enthusiastic diarist, he provides no account of its activities after that point. Although there were upsurges in sectarian violence in west Belfast around the time of the Truce and in North Queen Street-York Street in late August 1921, the UVF was not the only armed loyalist group in either area, so should not be assumed to have been the key participant in those outbreaks.

The Imperial Guards were definitely the most numerous loyalist paramilitary formation and also the least publicity-shy, placing recruitment advertisements in the unionist press and mobilising thousands for their initial church parades in November 1921. Even allowing for a certain element of boastful exaggeration, their claimed membership of 21,000 in the middle of that month clearly dwarfed those of the other groups.54

Although they were organised in battalions across the entire city and two members were killed on the Newtownards Road, most of what is known about their activities relate to north Belfast. As noted in relation to one company of their North East Battalion in part 1 of this post, those activities included armed robbery, intimidation, arson, the shooting of hostile witnesses, sectarian killings and the killing of a British soldier. But with the exception of the British Army fatality, none of these activities were unique to the Imperial Guards.

If the single defining characteristic of the Imperial Guards was their common record of service in the British Army during the Great War, the members of the UPA had other commonalities: Frederick Pollock and Robert Wadell, who lived two doors apart in Lord Street in Ballymacarrett, were a Queen’s Island heater boy and labourer respectively; Frederick Brereton and John Darley lived in numbers 25 and 26 Dunvegan Street and both worked in the crane department in Belfast Harbour. More strikingly, UPA members from its various branches shared lengthy criminal records: Alex Robinson’s internment file bluntly stated that his occupation was “corner boy.”55

The Ballymacarrett branch of the UPA had a membership of 150 according to the records seized by DI Spears. The fleeting reference to 200 “loyalists from the Shankill Road” in relation to the May Street squatters seems to suggest this was the membership of that branch. Assuming a similar figure for York Street and even a mere 50 for the Ormeau Road branch, the UPA therefore had an estimated total membership of roughly 600.

However, what they lacked in numbers, they made up for in terms of lethal violence. As noted in The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom, York Street-North Queen Street and Ballymacarrett were the two areas with the highest numbers of Catholics killed, at 53 and 36 respectively. These killings were not all the work of the UPA, as the Imperial Guards and Specials were also partly responsible – all three operated in both areas. But on a per-capita basis of killings per member, the intensity of the violence meted out by the UPA certainly exceeded that of the Imperial Guards. In addition, the UPA’s use of a flogging horse to punish its own members distinguish it as having a particularly pathological bent.

However, its violence was not primarily directed at the IRA, against whom the loyalists in and out of uniform were supposedly defending Ulster: only two of the 35 IRA and Fianna fatalities in Belfast occurred in York Street-North Queen Street, while only three were in Ballymacarrett. The other 84 Catholics killed in these two areas were civilians, among them 27 women and girls – those were the people targeted by loyalist paramilitaries.

Robert Simpson clearly spoke for the wider UPA membership when he trenchantly declared the real motivation for his actions: “I shall always hate Roman Catholics.”

References

1 Seán MacEntee to Éamon de Valera, 5 November 1921, UCD Archives, Richard Mulcahy Papers, Correspondence with Brigade Commandants 17-23 November 1921, P7/A/29.

2 Ibid.

3 Intelligence Officer, 3rd Northern Division to Michael Collins, n.d., Military Archives, Michael Collins Papers, Correspondence between Intelligence Officer 3 Northern Division & Intelligence Staff, GHQ, CP/05/02/23.

4 Belfast News-Letter, 1 August & 17 November 1921.

5 Colonel-Commandant David McGuinness, Special Constabulary (B Class), n.d. [early 1924], National Archive of Ireland, North East Boundary Bureau, Northern Ireland minorities, NEBB/1/1/12.

6 https://www.raobgle.org.uk/#About-Us

7 Belfast News-Letter, 19 December 1921.

8 Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 22 April 1922.

9 Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p270.

10 Ibid, p271.

11 District Inspector (DI) R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 29 October 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A.

12 Head Constable J. Wilkin to Detective Branch, RUC, 7 October 1922, PRONI, Williamson, John, Fortingale St, Belfast, HA/5/2210; Belfast News-Letter, 1 April 1922; https://nationalarchives.ie/collections/search-the-census/view-pdf/?doc=nai001455976.

13 City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 25 November 1922, PRONI, Williamson, John, Fortingale St, Belfast, HA/5/2210.

14 Notes of appearance before Advisory Committee, 30 November 1922, ibid.

15 DI John Nixon to City Commissioner, RUC, 5 March 1923, ibid.

16 Head Constable Major Osmonde to Adjutant, 1st West Belfast Battalion, C1 Special Constabulary, 21 August 1923, ibid.

17 Particulars of persons arrested, 23 October 1922 & City Commissioner to Inspector General, RUC, 29 October 1922, PRONI, Scott, George, Downing St, Belfast, HA/5/2205.

18 List of persons recommended for internment, n.d., ibid; Belfast News-Letter, 22 August & 29 November 1922.

19 S.E. Thompson to Minister of Home Affairs, 2 February 1922 & A.P. Magill to S.E. Thompson, 10 February 1922, PRONI, Forcible entry and possession of houses in May Street, Belfast, HA/5/876; S.E. Thompson to Minister of Home Affairs, 8 September 1922, PRONI, Forcible possession of property in May Street, CAB/9/B/41/1.

20 DI R.R. Spears to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 February 1923, PRONI, Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), report on activities, CAB/6/92.

21 Northern Whig, 28 April 1922.

22 Depositions of James Sharpe, Jane Doherty & Head Constable Phillip Gunn, 14 October 1921, PRONI, William Gregg – shooting at James Sharpe, BELF/1/1/2/66/14.

23 DI R.R. Spears to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 February 1923, PRONI, UPA, report on activities, CAB/6/92.

24 Jane Simpson to Minister of Home Affairs, 3 May 1922 & A.P. Magill minute, 7 June 1922, PRONI, Internment of Robert Simpson, Beersbridge Road, Belfast, HA/5/962B.

25 Robert Craig to Minister of Home Affairs, 10 July 1922, ibid.

26 DI R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 6 December 1922, ibid.

27 Notes of appearance before Advisory Committee, 6 June 1923, ibid.

28 Belfast News-Letter, 6 October 1922.

29 Archibald Pollock (Senior) to Minister of Home Affairs, 5 November 1922 & Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Pollock, Frederick, Lord St, Belfast, HA/5/2193.

30 (Pollock) DI R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 29 October 1922 & (Callow) Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A.

31 Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Arthurs, Joseph, Wolff St, Belfast, HA/5/2194.

32 Joseph Arthurs to Minister of Home Affairs, 19 October 1922 & DI R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 13 April 1923, ibid.

33 DI R.R. Spears to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 February 1923, PRONI, UPA, report on activities, CAB/6/92.

34 Ibid.

35 DI R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 29 October 1922, PRONI, Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A.

36 Robert Craig (Senior) to Minister of Home Affairs, 27 June 1923 & Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Craig, Robert, Convention St, Belfast, HA/5/2223.

37 Persons recommended for internment, n.d., Pentland, Thomas, Clonallen St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/2221.

38 Depositions of John Duggan, Edith Kane & Ellen McGlone, all 1 November 1921, PRONI, Thomas Pentland – murder of Murtagh McAstocker, BELF/1/1/2/66/5.

39 DI R.R. Spears to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 February 1923, PRONI, UPA, report on activities, CAB/6/92.

40 DI R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, RUC, 20 November 1922, PRONI, Waddell, Robert, Lord St, Belfast, HA/5/2220; Persons recommended for internment, n.d., Gray, George, Foundry St, Belfast, HA/5/2222.

41 Notes of appearance before Advisory Committee, 12 December 1922, PRONI, Brereton, Frederick, Dunvegan St, Belfast, HA/5/2248; Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Darley, John, Dunvegan St, Belfast, HA/5/2249.

42 DI R.R. Spears to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 February 1923, PRONI, UPA, report on activities, CAB/6/92; Belfast News-Letter, 24 February 1923.

43 Annie Armstrong to Minister of Home Affairs, 26 October 1922, PRONI, Robinson, Alexander, Andrew St, Belfast, HA/5/2192. This Annie Armstrong owned and lived above a pub on Peter’s Hill at the bottom of the Shankill Road.

44 Persons recommended for internment, n.d., & DI R.R. Heggart to City Commissioner, RUC, 28 October 1922, PRONI, Internee, William John Nesbitt, 47 Geoffrey St, Belfast, HA/32/1/390.

45 W.J. Nesbitt, 26 years, 47 Geoffrey St, Belfast, n.d., PRONI, Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A.

46 Notes of appearance before Advisory Committee, n.d, PRONI, Internee, William John Nesbitt, 47 Geoffrey St, Belfast, HA/32/1/390.

47 E.W. Shewell to Henry Toppin, 4 November 1922 & William Nesbitt to Minister of Home Affairs, 26 November 1922, ibid.

48 William Nesbitt to Minister of Home Affairs, 24 January 1923, ibid. Nesbitt’s note is transcribed exactly as he wrote it.

49 Annie Armstrong to Minister of Home Affairs, 31 July 1923 & High Commissioner for Australia to Minister of Home Affairs, 24 August 1923, ibid. This Annie Armstrong lived in Balmoral; her handwriting was distinctively different from that of the woman of the same name who owned the pub on Peter’s Hill.

50 Henry Toppin to Inspector General, RUC, 5 September 1923, ibid.

51 Inspector General, RUC, to Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, 25 September 1923, ibid; Persons recommended for internment, n.d., PRONI, Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A. This Robert Craig from Nile Street appears to be unrelated to the Robert Craig from Ballymacarrett.

52 Minute sheet, 2 July 1935, PRONI, Internee, William John Nesbitt, 47 Geoffrey St, Belfast, HA/32/1/390.

53 Frederick Crawford, History of the Formation of the Ulster Brotherhood, 14 June 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/12/1; Robert Craig to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 May 1923, PRONI, Craig, Robert, Convention St, Belfast, HA/5/2223.

54 Belfast News-Letter, 17 November 1921.

55 Particulars of persons arrested under Regulation 23 of Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act, 6 October 1922, PRONI, Robinson, Alexander, Andrew St, Belfast, HA/5/2192.

Leave a comment