In The Factory of Grievances, Patrick Buckland wrote that when confronting the threat posed by the IRA, leading unionists were quite prepared to ignore legal boundaries: “the policy of recruiting extreme gangs was symptomatic of what Spender [Wilfrid Spender, Cabinet Secretary to the Government of Northern Ireland] complained was a widely held view at the Ministry of Home Affairs – ‘that the law does not matter when dealing with suspected treasonable criminals.’”1

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes

The revival of the Ulster Volunteer Force

The relationship between James Craig’s Unionist Party and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was identical to that between Sinn Féin and the IRA at the time: the Unionist Party was the political wing and the UVF was the armed wing. The Belfast Street Directory of 1918 helpfully noted that the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) and UVF were both based in the Old Town Hall in Victoria Street. Further illustrating the symbiotic connection between the two, Richard Dawson Bates was listed as the secretary of both organisations.2

The Old Town Hall in Victoria Street, the shared headquarters of the Unionist Party and the UVF

The UVF had been kept going on a skeleton basis during the Great War, as large numbers of its men were serving with the British Army. However, on 1 May 1919, its General Officer Commanding, Lieutenant General George Richardson, announced that its remaining members were being stood down: “(1) Existing conditions call for the demobilisation of the Ulster Volunteers. (2) The Force was organised, to protect the interests of the province of Ulster, at a time when trouble threatened.”3

In late May 1920, as the republican struggle for independence grew both in momentum and proximity to the north, the UUC began making behind-the-scenes preparations to revive the UVF:

“Some eight weeks ago I got D.[Dawson] Bates to call together the leaders of the UU Council and to formulate a policy, as the rank and file thought they were going to be left to look after themselves. The outcome of this meeting was to ginger up the Unionist Clubs and to enrol for the UVF.”4

Shortly after Edward Carson’s speech on the Twelfth in 1920, at which he threatened the British government, “We will re-organise, as we feel bound to do in our own defence, throughout the province the Ulster Volunteer Force,” the UUC went public and announced that Lieutenant Colonel Wilfrid Spender had been appointed as the UVF’s new commander: “All loyalists should report to their battalions.” Confusingly, when Spender was interviewed, “He added that there was no urgency to report.”5

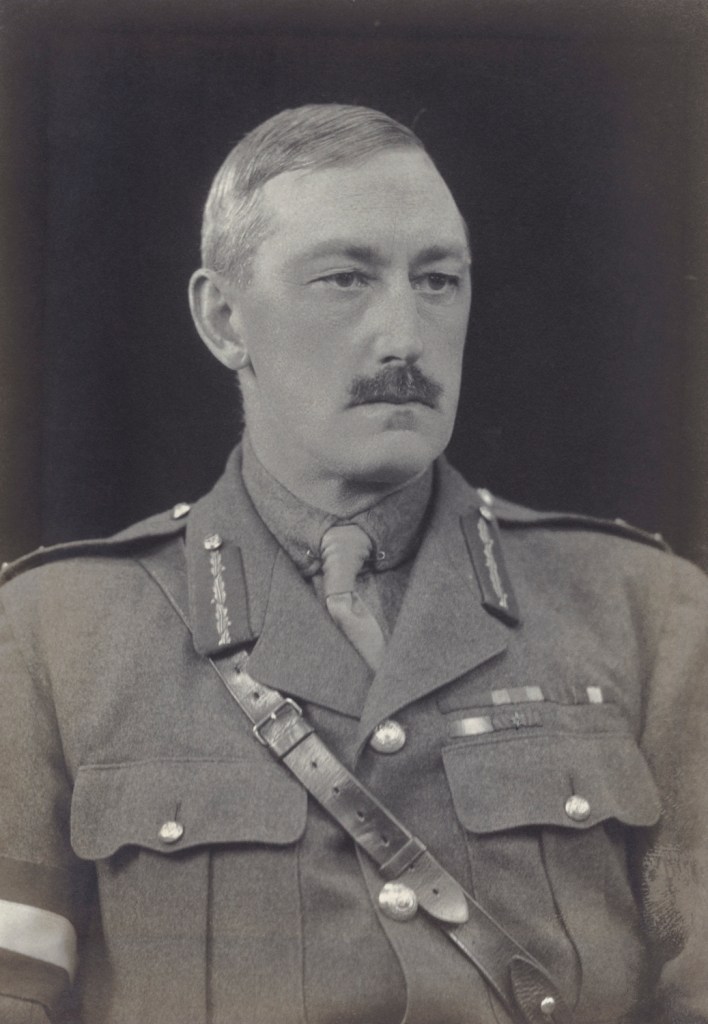

Wilfrid Spender was the first commander of the revived UVF

This lackadaisical attitude on the part of its new commander may explain why the revival itself was lacklustre:

“While the original 20 UVF battalions in Belfast had been revived, they seem to have contained little more than 100 men each, meaning that they were under-strength companies in military terms. Spender himself was concerned about the organisation in Co. Antrim and South Belfast and also noted that, ‘In the doubtful districts the people will watch to see how things pan out before committing themselves.’”6

The rebirth of the UVF was largely superseded by the decision of the British government on 9 September 1920 to establish a Special Constabulary, only later known as the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”). This new force had certain advantages in terms of attractiveness compared to the UVF, most notably the fact that A and B Specials would be paid either full-time wages or part-time allowances respectively.

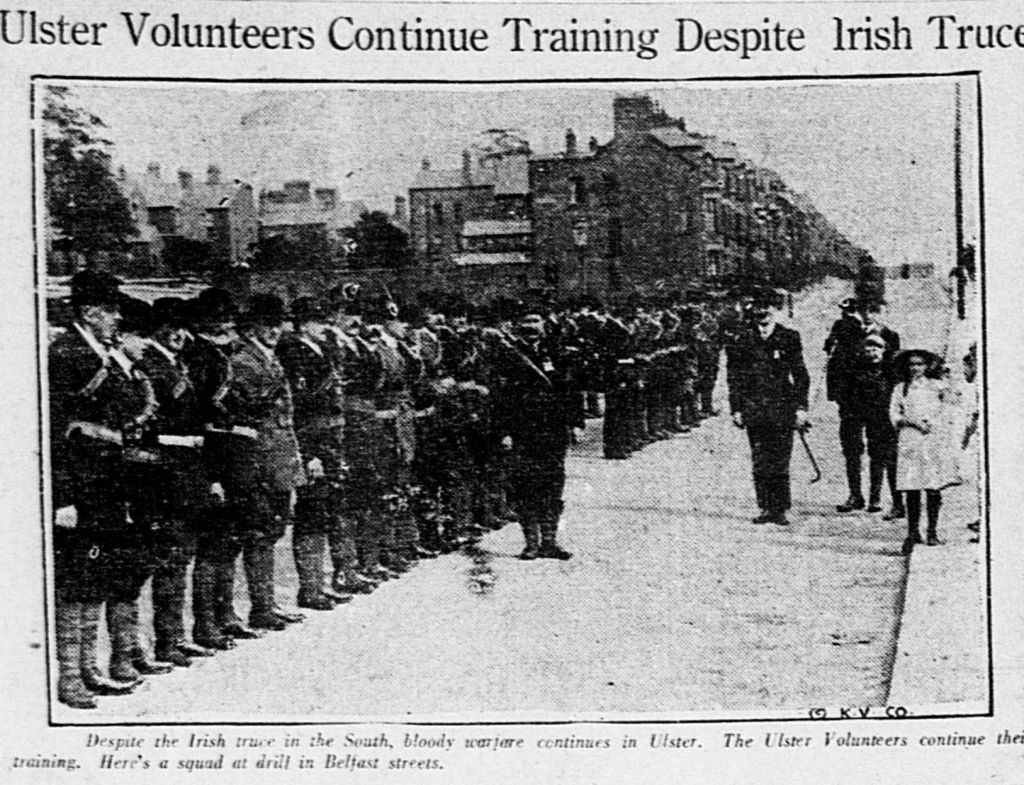

However, the Truce of July 1921, under the terms of which the B Specials were demobilised, injected fresh impetus into the UVF revival.

The revival of the UVF received new impetus from the demobilisation of the B Specials under the terms of the Truce (Colombian Evening Missourian, 15 September 1921)

The British Army was uneasy about this development. At a meeting with the northern Prime Minister, James Craig, on 20 October 1921, the General Officer Commanding, Ireland, General Neville Macready, said that “he was somewhat concerned with the news that the UVF was being reorganised.” Craig told him this was happening because loyalists were worried about the prospect of a renewed IRA campaign in the north while the authorities did nothing to avert it.7

Fred Crawford had been the architect of the UVF’s 1914 gunrunning operation, in which 25,000 rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition were landed at Larne, Bangor and Donaghadee. After Spender was appointed as cabinet secretary to the northern government in June 1921, he was replaced as UVF commander by Crawford. In October, Crawford approached Craig:

“I put it to the premier that if something were not done our people would get out of hand, that there would be hell let loose and the devil to pay…what I feared more than the enemy was our breaking out because our people were so exasperated that it was almost impossible to keep them in hand…It is better to have the old UVF pulled together with its traditions and discipline than have irresponsible individuals enlisting a lot of scallywags who will only be a menace and a danger to our cause.8

He was particularly concerned at the prospect of new groups forming which might be less than amenable to direction by the Unionist Party establishment: “I also pointed out that there were a number of societies springing up with rash and irresponsible leaders and that their ranks were being filled up with some good men but mostly composed of those who are either on the make or out for loot.”9

Craig’s government had similar concerns. Its solution, once the British government confirmed that policing and security powers would be handed over on 22 November 1921, was to try to bring the various loyalists paramilitaries inside the USC tent, in the hope that discipline and control could be maintained.

Crawford was relieved:

“Yesterday [14 November 1921] I called a meeting of the old military commanders of the UVF to discuss the formation of a new ‘C’ force…the northern government have expressed a wish to get them all into one force to be called the ‘C’ Force, which will be a striking force properly organised. Spender is specially interested and responsible for getting detail of the new ‘C’ force.”10

C1 Specials in Chichester Street: Craig’s government planned to absorb loyalist paramilitaries into the new force

Many – but not all – of the arms and ammunition imported by the UVF were placed under the control of the authorities during the Great War. These weapons were stored under military guard at a warehouse in Tamar Street in east Belfast and the bolts were removed to make them unusable. Curiously, all concerned seemed to have regarded them as still being the property of the UVF.

When it seemed possible that there would be insufficient rifles for the remobilised B Specials, Spender approached Crawford about the feasibility of handing over the Tamar Street arms dump for use by the Specials. Crawford agreed and began testing the rifles and ammunition.11

In mid-November, Major General Archibald Cameron, the British Army’s General Officer Commanding, Ulster, gave permission for the rifle bolts to be re-fitted, but in the event, service rifles for the B Specials were supplied by the British government and the UVF weapons remained in Tamar Street.12

After the decision at the end of November 1921 to proceed with the formation of the new C1 Specials, the UVF seems to have been completely subsumed into the new body and Crawford himself became District Commandant of the B Specials in South Belfast.

The attempts to revive the UVF after 1920 do not appear to have been more than sporadic:

“…it is noticeable that the UVF never had a formal disbandment or even Home Guard style stand down at any stage; possibly so that attention would not be drawn to the extent to which the formation of 1920-22 was such a pale shadow of that of 1913-14.”13

The Ulster Brotherhood: “Crawford’s Tigers”

Crawford’s involvement in the Larne gunrunning suggests that he had a conspiratorial nature. The UVF was not the only such iron that he had in the fire.

He felt that the republican insurgency deserved a blunt response: “There is only one way to deal with the campaign of murder that the rebels are pursuing and that is, where the murder of a policeman or other official takes place, the leading rebel in the district ought to be shot or done away with.”14

After the IRA’s killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn in August 1920, Crawford approached John Gelston, the Belfast City Commissioner of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), telling him:

“…the only way to save Ulster from Sinn Fein crime generally was to allow some prominent citizen to get together a lot of civilians and get them into an organised body, with permission to carry arms at all times. They would mix with the crowd and no one would know who they were, but in case of an outrage taking place they would be on the spot and use their weapons to shoot assassins.”15

Gelston agreed with the sentiment but felt that the British authorities in Dublin Castle would not approve.

When the IRA began killing policemen regularly in Belfast in the spring of 1921, Crawford contacted the RIC’s Divisional Commissioner, Charles Wickham, setting out his plan once more:

“Two hundred to five hundred men to be armed and to frequent, in ordinary civilian clothes, all places where trouble was to be anticipated. They ought to go about in twos and threes, threes preferably, not necessarily together, but within twenty or thirty yards of each other.

The organisation should be as follows:

Head, to be some person well known for his pluck and determination to all the rank and file, so that they would fully trust and obey him.”16

Crawford clearly felt his own pluck and determination were sufficiently well-known for him to fill this role himself. He envisaged a cellular structure, bound by an oath of secrecy:

“The rank and file to be composed of a leader of each nine men. In other words, three squads of three men, one to be leader, and two others.

As this organisation is to be kept as secret as possible, so as to be of effective use, the rank and file outside of their own immediate squad should not be told who else was in the force. The squad leaders need not necessarily know each other. In fact the fewer of all ranks that know each other, the better…All these men will be put under a solemn oath not to divulge anything to an unauthorised person. This oath will be quite independent to the Oath of Allegiance, and if possible more binding.”17

He wanted to report directly to General Harry Tudor, the Chief of Police for Ireland, but otherwise, to have a carte blanche: “The Head of this force will only be responsible to the Chief of Police for the orders and discipline of the force, and he must be so trusted to properly use his judgment that he will have a very free hand so far as his policy is concerned.”18

Fred Crawford founded a paramilitary group which bore his name

By now, attitudes in Dublin towards extra-legal methods had softened. When Tudor visited Belfast, Crawford met him – Tudor wanted to know how soon he could assemble the force, to be known officially as the “Detective Reserve.” Crawford began recruiting:

“On May 14 I called the first meeting to inaugurate the founding of the ‘Ulster Brotherhood’ in the Old Town Hall at 3.00pm…It was an essential point that each member had to own either of following weapons and 100 rounds of ammunition: Webley or other .45 revolver, Martini Henry rifle, or short Winchester rifle USA Cavalry pattern.”19

At a subsequent meeting a week later, 200 more volunteers turned up; by mid-June, five meetings had been held: “…now we have the society fairly started and on its legs. Already the members are called Crawford’s Toughs or Tigers.”20

The oath which Crawford administered to his Tigers is a masterpiece of paranoia, violent intent and promises of lethal retribution in the event of betrayal. It begins with a lengthy requirement for secrecy and silence:

‘I, …., in the sight of God, and I value my ultimate eternal Salvation, do hereby voluntarily and without outside pressure or persuasion of any sort solemnly vow and promise that I will never mention to any person or persons, or write, delineate legibly, intelligibly, anything that can or may be read or interpreted, making known thereby that I belong to his Brotherhood, and I vow and promise that I shall never divulge anything whatever relative to this Brotherhood, except to those duly authorised by my superiors to receive this information. I do further vow and promise that I will not divulge by any means the names of any of the members of this Brotherhood, more especially the Head and his Adjutant.”21

It then moves on to promise very public vengeance against republicans:

“The sole object of my joining this Brotherhood is to uphold the Protestant religion, to retain an open bible, and to establish full freedom religiously and politically for all, and to destroy and wipe out from Ulster by every means in my power the foul Sinn Fein conspiracy of murder, assassination, and outrage, which at present is so rampant throughout all the rest of Ireland.”22

The oath concludes by returning to the theme of secrecy, with catastrophic punishments for anyone found to be in breach of the Tigers’ code:

“Should I wilfully break or violate this oath, either whilst a member of the Brotherhood, or at any time after I may have resigned, or be removed from same, or the Brotherhood has ceased to exist, I shall be guilty of perjury of the vilest and grossest kind, and shall thereby bring upon myself the penalty of being shot through my treacherous and unworthy heart by any member of the Brotherhood, or punished in such other way the brethren may think fit.”23

The Tigers were deployed on at least one occasion, in June 1921, although that turned out to be uneventful: “20 men were detailed for duty on 22nd inst., no arrests were made, several suspects were held up and searched. Arms, ammunition etc, etc, will be returned complete on Monday next.”24

The Truce situation, with the enforced absence of the B Specials, was irksome to Crawford’s men: “My Tigers are very difficult just now to keep in hand. In fact, except the Government (Ulster) gets some force up to meet the present emergency there will be trouble that they will not be able to cope with.”25

Like the UVF, Crawford’s group appear to have been absorbed into the C1 Specials, as the last mention of them in his diary came at the end of November: “Called and saw Wickham today. Had a chat with him about the new ‘C’ force and asked him about the Tigers.”26

The Ulster Imperial Guards

The Ulster Imperial Guards had their roots in the Ulster Ex-Servicemen’s Association (UESA), which was a breakaway from a UK-wide organisation, the Comrades of the Great War. Like other such groups, it was primarily concerned with lobbying on behalf of veterans, particularly in relation to securing employment for former soldiers and medical care for those who had been wounded or disabled.

The UESA was formed in 1919 and wrote to Carson in November of that year, inviting him to become their president and claiming that “Our members are all loyal Ulster men and 95% are Orangemen.” According to Austen Morgan, Carson consulted Bates, who didn’t attempt to hide his class prejudice when he replied that “The UESA was small, and had, in its leadership, few people of ‘standing.’”27

Already president of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA), Carson became vice-president of the UESA. Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh has noted that correspondence between the two groups and Carson “clearly suggests that both groups wanted to discuss matters better left to personal and private conversation rather than the written record…the UESA argued that ‘if I had a private interview with you, I could explain more in person than in writing.’”28

Just over a month before the start of the Pogrom, “On 18 June 1920, the UESA sent Carson a telegram, pledging by ‘all means in our power to restore law and order in Ulster.’”29

Both they and the UULA were heavily involved in the initial shipyard expulsions. That socialists and trade unionists, the so-called “rotten Prods,” were a particular focus of their anger was clear from the speech made by a prominent UESA leader at the founding of a new branch in Lisburn: “Mr Robert Boyd, organising secretary, gave a detailed account of the aims and objects of the Association. Their aim was to bind all Protestant loyal ex-service men together. They drew the line at red flaggers, Bolsheviks, and extreme socialists.”30

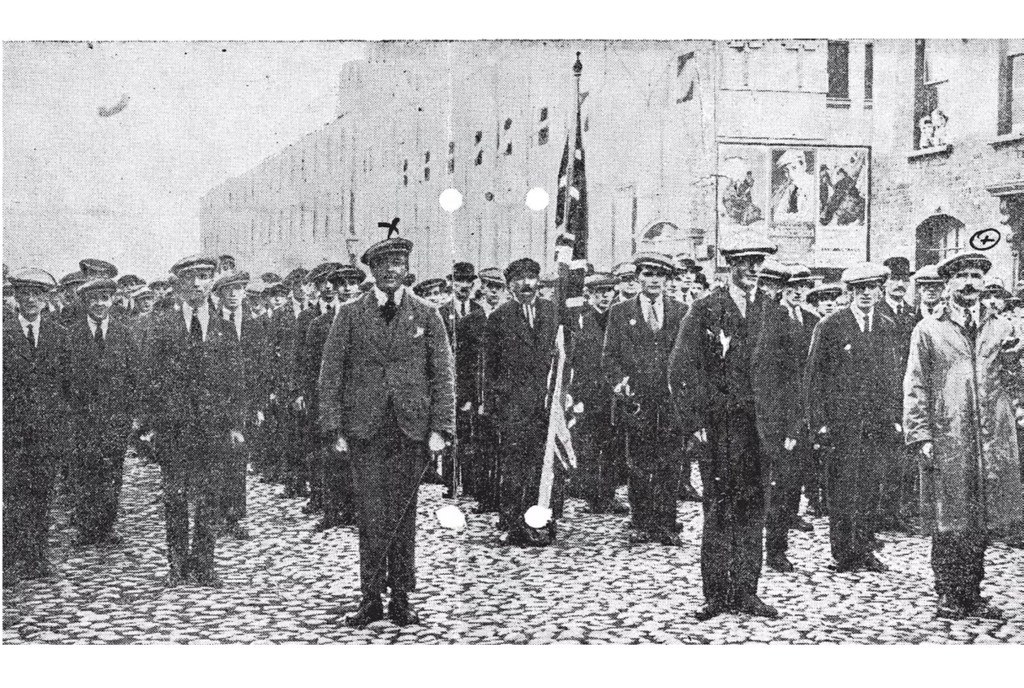

By the spring of 1921, Boyd noted in a report that the UESA had grown to a membership of 8,000. The extreme right-wing nature of the organisation was further evidenced when, acting alongside the proto-fascist British Empire Union, Boyd organised a march of shipyard workers to the Ulster Hall on 17 May 1921, occupying the hall and thereby preventing an election meeting for Belfast Labour Party candidates from proceeding as planned.31

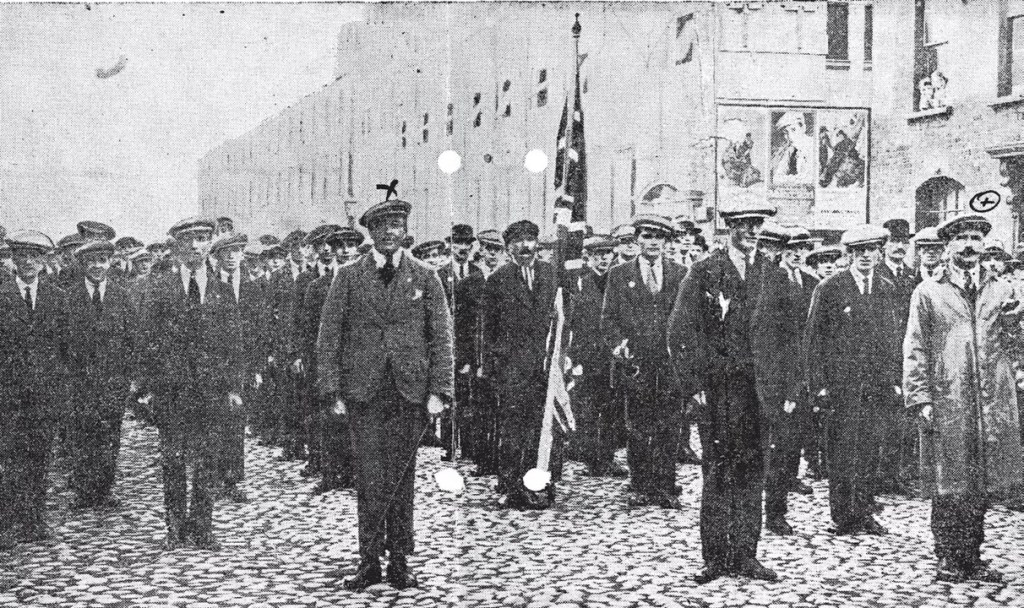

Shipyard workers on a march organised by UESA and the British Empire Union to prevent a Belfast Labour Party election meeting from going ahead

The formation of the Imperial Guards as a paramilitary wing of the UESA was first advocated by Boyd at a meeting of the UESA steering committee meeting on 28 July 1921, just over a fortnight after the start of the Truce which demobilised the B Specials, when he said that:

“…in his opinion the time had come not for words but for action, and he advocated immediate action in transforming the Association into a Territorial Force, under the direct control of competent military officers. This could be done at once. Men of the calibre of the Ulster Ex-Servicemen’s Association would be a distinct acquisition to any government, and they could be relied upon to uphold the laws and constitutions of the province. They were trained and had discipline. By their love of country they had helped to save the Empire. Every country had its Territorial Force. Why not Ulster?”32

News that Boyd’s proposal had been accepted and was being acted on soon reached the Northern Ireland government – at the end of August 1921, a cabinet meeting noted that “A private meeting has been summoned by certain individuals for the purpose of organising a defence force of loyalists.”33

Recruitment into the Imperial Guards continued during the autumn and on 29 October, its North East Battalion held a parade on the York Road. Further illustrating the shared working-class background of the UULA, UESA and Imperial Guards, a UULA councillor, James Turkington, was pictured at the centre of a group of Imperial Guards officers on that occasion and at the head of the parade itself.

Imperial Guards parade on York Road (© Belfast Telegraph, 1 November 1921. Reproduced by kind permission of UCD Archives, Richard Mulcahy Papers, P7/A/29).

Two weeks later, on Sunday 13 November, the Imperial Guards, by now organised into seven geographically-based battalions in Belfast, staged an initial show of force when they held a series of church parades across the city.

These parades were enthusiastically reported by the unionist press the following day, listing the commandants of the different battalions as being Major Gerald Ewart (North), Captain Clapton (North East), Captain Mayes (South), W.J. Steele (East), Major P.B. Lewis (West) and J. Wright (Ligoniel); the commandant of the South West Battalion was not named. In addition, various lower-ranking Imperial Guards officers were also named.34

The Imperial Guards could also boast of significant political support: three Unionist MPs, including William Twadell and William Coote, marched at the head of the West Battalion parade, as well as two Justices of the Peace; a fourth MP sent his apologies as he was unwell, while a fifth MP attended the church service.35

The emergence of the Imperial Guards was not universally welcomed within unionism – two days after the church parades, Crawford noted in his diary that there was particular tension between the Imperial Guards and the UVF: “The Ex-Service Men’s Association started to enrol men as a defence force and now call themselves the Ulster Imperial Guard. There has been more or less jealousy with them because of the UVF, which is being reorganised.”36

The northern government decided to include the Imperial Guards among the paramilitary groups which it aimed to co-opt into the new C1 Specials. Crawford acted quickly to put this decision into effect:

“At my request Captain Dixon [Herbert Dixon, Chief Whip of the Unionist Party] has called a meeting for next Thursday of the leading citizens who took part in raising the UVF, to meet the Battalion Commanders, also the representatives of the Ulster Imperial Guard, with a view to discussing the best methods of inaugurating the ‘C’ Force. It will be a difficult problem for us to solve as there are so many conflicting interests at stake.”37

In the event, the Imperial Guards showed their disdain for their UVF rivals by simply ignoring the invitation, as a crestfallen Crawford was forced to note: “This meeting took place but was not much use as Dixon had no definite proposals to put before the meeting, and, besides, the representatives of the Imperial Guard did not turn up.”38

Not alone was the UVF resentful at the emergence of such a formidable loyalist competitor, but according to Timothy Bowman, the British Army was positively alarmed: “General Cameron believed that the Ulster Imperial Guards posed a severe political threat to the Northern Ireland government, noting [on 9 January 1922], ‘Boyd is a regular kind of Bolshevist’ who had threatened that his men would take control of the USC.”39

They did not even have to do this clandestinely – instead, the City Commandant of the Specials went to them looking for recruits:

Major General Archibald Cameron was alarmed at the emergence of the Imperial Guards

”At the meeting, Colonel Goodwin stressed his manpower shortages in the Special Constabulary and his wish to absorb the Imperial Guards. The Imps agreed to help…In March 1922, the Belfast Imps, among them the city’s most dangerous paramilitaries, were recruited en masse as ‘C1’ special constables.”40

A C1 Specials’ “Order of Battle & Location List” from late 1922 illustrates the extent to which Imperial Guards succeeded in securing leading officer roles in the USC.

Captain Sam Waring, named in press reports of the November 1921 mobilisation as one of the leading officers in the North Battalion, was Adjutant of the 1st North Belfast District of the C1s. Lieutenant R. McCord, commander of the Imperial Guards’ D Company in the same battalion, also commanded No. 6 Platoon, C Company of the 1st North Belfast C1s. Similarly, Lieutenant Joseph Cunningham, named as an officer in the Imperial Guards’ West Battalion, also commanded No. 2 Platoon, A Company of the 1st West Belfast C1s. John Kelly was another company commander in the Imperial Guards’ North Battalion – Edward Burke says he was also an officer in the C1s.41

Not was the Imperial Guards’ infiltration limited to the C1 Specials. Major Gerald Ewart led the North Battalion of the Imperial Guards; he was also a District Commandant in the B Specials. He had personal reasons for loathing nationalists: according to Crawford, District Inspector Swanzy had been walking between Ewart and his father when the IRA killed Swanzy. Elsewhere, IRA intelligence believed that Captain Mayes of the South Battalion was also a B Special.42

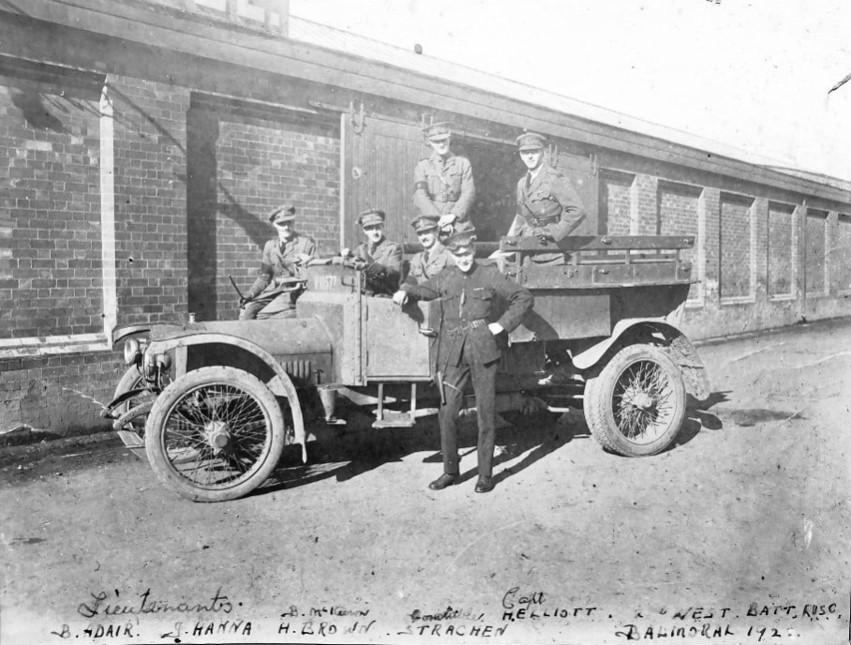

Officers of the 2nd West Belfast Battalion, C1 Specials; several Imperial Guards officers were also officers in the C1 Specials

At one point, as well as providing the C1 Specials with manpower, it appeared that, due to a Northern Ireland government shortage of rifles, the Imperial Guards might also have to supply the C1s with weapons, so the Ministry of Home Affairs made arrangements to that effect. However, that potential embarrassment was averted in March 1922:

“The fact that the Tamar Street arms were now available made it unnecessary to rely on the Imperial Guards for the supply of arms for that C2 [sic] force; in view of the changed situation in this respect it was determined that the previous agreement should be varied in accordance with the Field Marshal’s recommendations.”43

As regards the activities of the Imperial Guards, the ripples outward from a single, relatively minor, armed robbery provide a snapshot of one company in the organisation and what its members did.

At the start of May 1922, a newspaper report mentioned the dropping of charges against a number of men alleged to have been involved in an armed robbery the previous autumn:

“A nolle prosequi was entered by the Crown…in the case of Joseph Gault, Joseph McKee, William Fannon, H[erbert]. Phillips, and George Elliott, charged with having entered with arms the licensed premises of Patrick Connolly, 100, Duncairn Gardens, on the 7th October…on the want of evidence through death.”44

The death in question was that of the principal eyewitness against the men: Patrick Connolly was killed in his spirit grocery in Duncairn Gardens on 21 November 1921, six weeks after the original robbery.

As regards the defendants, Gault, from Earl Street between North Queen Street and Corporation Street, was included on a list of Imperial Guards supplied by the Fianna to the IRA’s Belfast Brigade Intelligence Officer.45

McKee, from North Ann Street in Sailortown, was identified by the IRA as being both an Imperial Guard and a B Special. So was Joseph Clarke of Nelson Street. The Fianna listed Barnsley Sloan from North Thomas Street as being an Imperial Guard and the IRA further identified him as an A Special.46

An Orange arch in Nelson Street, where Imperial Guards intimidated Josehine Moan and her children from their home, then burned it (© National Museums Northern Ireland)

All three – McKee, Clarke and Sloan – appeared in court, charged with of intimidating a Catholic woman, Josephine Moan, and her children from their home at 149 Nelson Street, then burning it. At teatime on 2 January 1922, three men carrying rifles climbed over her back wall. She recognised all of the attackers: McKee “lives in the house opposite my back door;” “I was reared along with Joseph Clarke,” a neighbour who lived across the street at number 116; Sloan was also a neighbour from a couple of streets away. When McKee shouted, “Get out of the house, it’s time you were out of that,” Sloan argued, “Don’t let them out, burn them.” Clarke, who was also carrying a tin of petrol, threatened to “blow her brains out if she did not,” so she and her aunt grabbed the children and ran. Accompanied by police, she returned later that evening to find “the house had been set fire to and a great deal of damage had been done.”47

Herbert Phillips, who lived off Great Georges Street, was also an Imperial Guard. He did not survive to go on trial for the Duncairn Gardens robbery – he was killed in Molyneaux Street, close to where he lived, on 22 November 1921. His funeral was held two days later.

James Galbraith of 5 Vere Street was also listed by the Fianna as an Imperial Guard. He was charged with the attempted murder of a Catholic neighbour, a boy named Patrick McGurnaghan who lived at number 63 on the same street on 24 November, the day of Phillips’ funeral.

The boy told the court:

“When I came near my own door I saw the prisoner standing near the corner of Dale Street. He was wearing a blue vest and a blue pair of trousers. He had no coat or cap. He had a rifle in his hands. He was about 25 or 30 yards from me. He bent down and fired a shot…I felt a stinging pain and discovered that I had been shot. The bullet entered below my right breast and passed out the back.”48

His sister saw him being shot and ran to his aid, as did a neighbour from across the street, Minnie Parkes, who shouted “All right Galbraith, you’ll not get away with that.”49

Apart from McGurnaghan being a Catholic, Galbraith may have had an additional reason for targeting that boy in particular. Four months earlier, the lad had given evidence in the trial of another Vere Street loyalist, Thomas Saunders, who was charged with firing shots across North Queen Street into the New Lodge Road the previous March – a Catholic woman, Sarah Bannon, who had been standing in the front room of her home, was wounded in the mouth.50

When Galbraith came to be tried for shooting the boy, an alibi was provided by his Imperial Guards company commander, James McMichael, who said that Galbraith was part of the detachment under his command that had marched in Phillips’ funeral cortege. Sloan and another Imperial Guard, George Harper from Sussex Street (also named in the Fianna document), provided similar alibis, saying that they had marched alongside Galbraith.51

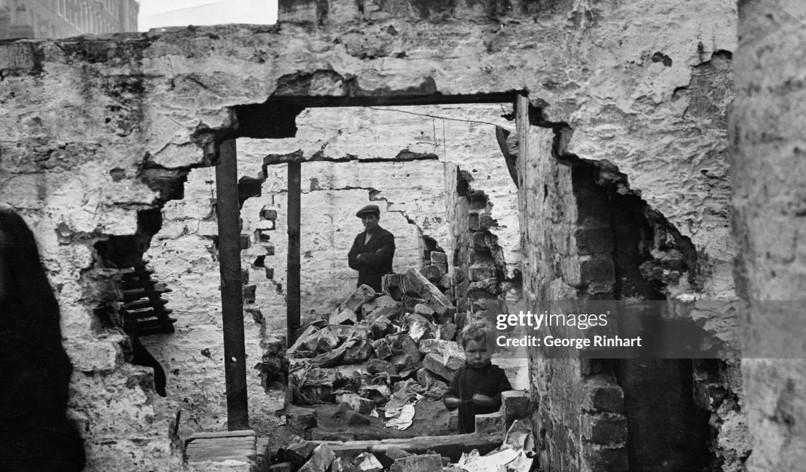

Back yards of houses in Vere Street tunnelled through by residents so that they could move about without being seen by snipers

Harper also had no compunctions about silencing witnesses. Catherine Kearney, another Vere Street Catholic, had given evidence against a friend of his in a court case in March 1921, after which Harper was “in the habit of threatening me.”52

On the night of 14 August, according to her mother, Harper come to their front door, “the worse for drink,” threatening that “he would come in either before curfew or after it and that he would neither use hands nor feet on her but would give her the contents of what was in his pocket.”53

She sent for her daughter, who later said:

“I was going home at about 10.25pm. I saw defendant in Dale Street which is off the street where I live. He was holding a revolver in his right hand. Some person shouted ‘There’s Kitty Kearney’ and immediately defendant fired at me. I stood in a doorway and heard a number of shots. I remained there till the police came upon the scene.”54

But on this occasion, Harper was found not guilty.

He was almost certainly the George Harper of Sussex Street who was reported as having accidentally shot himself in the hand two months later, while handling a revolver in Mountcollyer Street near Tiger’s Bay, also in north Belfast. Although he was treated in the Royal Victoria Hospital for his wound, there were no subsequent reports in either police files or the press as to why he had been handling a revolver.55

Far more seriously, Harper was believed by the Norfolk Regiment to have killed one of its soldiers, Private Ernest Barnes, in Sussex Street on 2 January 1922. Citing documents compiled by the regiment’s intelligence officers, Burke has described the incident:

“Later intelligence indicated that Private Barnes was now the target of the Imps’ most feared sniper, Jordy Harper, a veteran of the First World War. Harper’s first shot missed; Barnes’ corporal raised his rifle and replied. Jordy Harper then cooly advanced through the fog towards the soldiers, firing twice before disappearing down nearby Dale Street – one of these rounds fatally wounded Barnes in the chest.”56

The killing of Private Barnes was in revenge for British troops having shot dead an Imperial Guard, Alexander Turtle, in Sailortown earlier that day.

Apart from Phillips and Turtle, three other Imperial Guards, very likely also members of McMichael’s company, were killed in or near North Queen Street: Andrew James (in Earl Street on 21 November 1921), Ben Lundy (in North Queen Street on 13 February 1922) and Herbert Hazzard (in Isabella Street on 8 March 1922). Like Turtle, Lundy and Hazzard were killed by British troops.57

Following Hazzard’s death, the 1st Battalion of the Imperial Guards placed a notice in the Belfast Telegraph, asking all members to attend the funeral. As the cortege neared Carnmoney Cemetery in Whiteabbey, north of the city, it diverted from the originally-planned route. Accounts of what ensued differed.58

According to the unionist Belfast Telegraph, a woman shouted, “Up the rebels” and rifle shots were fired from a nearby railway track. However, a police report stated that a Reverend Cochrane who had been accompanying the funeral “cannot say that the funeral was fired on by nationalists.”59

The nationalist Irish News carried a more detailed report on the events. Groups of armed men, who had formed a vanguard and rearguard for the funeral proper, broke away and at gunpoint, demanded that residents draw their blinds as a sign of respect. A Protestant butcher named Fleming was fired at, a bomb was thrown into one house, while others were wrecked by intruders; Emmet Hall, a nationalist venue, was smashed up and set on fire.60

As the funeral passed, Hugh McAnaney, a Catholic carter, got down off his cart and removed his cap. He was within sight of his home and his wife watched in horror as he started to remount his cart but then jumped down and tried to escape a group of men who fired at him. A Protestant woman tried in vain to save him but his attackers shot him on the ground. His stepdaughter came running and he asked her to get him a drink of water: “One of the murder gang, hearing the poor fellow’s request for a drink, turned back and said, ‘I’ll give him a drink,’ and, pulling out a revolver, shot the wounded man through the head, killing him instantly.”61

The police said that the Protestant woman had given them a description of one of those who had shot the victim : “It is believed he belongs to the York Road quarter Belfast where the police are making all possible enquiries.” They also took a statement from an Imperial Guard who inadvertently corroborated the Irish News’ version of events: “Charles McKinnon – in charge of 1st Batt. Ulster Imperial Guards…says he blew a whistle and ordered the men to rejoin the funeral.”62

McAnaney’s killers were never caught.

In the warrens of cramped terraced houses off North Queen Street and in Sailortown, with their mottled religious makeup, grudges were nursed and sectarian hatred festered. This single unit of the Imperial Guards was involved in armed robbery, intimidation, arson, attempting to shoot hostile witnesses, attempted and actual sectarian killings, the killing of a British soldier and, in turn, were themselves killed by British soldiers.

For these veterans of the Great War, it was all a far cry from the heroic attempt to capture the Schwaben Redoubt on the first morning of the Battle of the Somme.

Part 2 of this post will examine the Cromwell Clubs and the Ulster Protestant Association.

References

1 Patrick Buckland, The Factory of Grievances: Devolved Government in Northern Ireland 1921-39 (Dublin, Gill and Macmillan, 1979), p217.

2 Belfast Street Directory, 1918, https://www.lennonwylie.co.uk/tuvcomplete1918.htm

3 Timothy Bowman, Carson’s Army: The Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910-22 (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2012), p183.

4 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 27 July 1920, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Private papers of Colonel F.H. Crawford (Crawford Papers), D640/11/1.

5 Belfast News-Letter, 13 & 24 July 1920.

6 Bowman, Carson’s Army, pp192-193.

7 Conference at Cabin Hill, Knock, 20 October 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

8 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 27 October 1921, PRONI, Crawford papers, D640/11/1.

9 Ibid.

10 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 15 November 1921, ibid.

11 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 14 November 1921, ibid.

12 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 15 November 1921, ibid.

13 Bowman, Carson’s Army, p201.

14 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 27 September 1920, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/11/1.

15 Frederick Crawford, History of the Formation of the Ulster Brotherhood, 14 June 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/12/1.

16 Frederick Crawford to Divisional Commissioner, RIC, 26 April 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/4/2.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Frederick Crawford, History of the Formation of the Ulster Brotherhood, 14 June 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/12/1.

20 Ibid.

21 Oath of The Tigers secret society, n.d., PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/15/2.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 H. Wright, Assistant Adjutant, to Frederick Crawford, 23 June 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/12/8.

25 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 15 November 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/11/1.

26 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 29 November 1921, ibid.

27 Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p263.

28 Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, ‘The Belfast Pogrom and the Interminable Irish Question’ in Studi irlandesi A Journal of Irish Studies, Volume 12, June 2022, pp171-193.

29 Ibid.

30 Northern Whig, 14 March 1921.

31 Belfast News-Letter, 1 April 1921; Morgan, Labour and Partition, p263.

32 Belfast News-Letter, 1 August 1921.

33 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 31 August 1921, PRONI, CAB/4/17.

34 Belfast News-Letter, Northern Whig & Belfast Telegraph, 14 November 1921.

35 Ibid.

36 Frederick Crawford diary entry, 15 November 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/11/1.

37 Frederick Crawford, Notes regarding proposed formation of “C” force from UVF, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/9.

38 Ibid.

39 Bowman, Carson’s Army, p200.

40 Edward Burke, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2024), p58.

41 Belfast Telegraph & Northern Whig, 14 November 1921; Order of Battle & Location List, C1 Special Constabulary, n.d., [1922], Military and police, general correspondence file, October 1922 – December 1922, PRONI, CAB/6/31; Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p58.

42 (Ewart) Captured IRA document, n.d., PRONI, Internment of Henry Crofton, HA/5/961A; Frederick Crawford diary entry, 11 September 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D640/11/1; (Mayes) List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes, July 1922, in List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th 1922, Military Archives (MA), Historical Section Collection (HSC), HS/A/0988/15.

43 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 27 March 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/37.

44 Northern Whig, 4 May 1922.

45 Intelligence Officer, Fianna Belfast to Intelligence Officer, Belfast Brigade, IRA, 17 March 1922, PRONI, Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, HA/32/1/130.

46 List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes, July 1922, in List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th 1922, MA, HSC, HS/A/0988/15.

47 Information forms of Josephine Moan & Mathilda Bohan, 7 January 1922, PRONI, Barnsley Sloan, Joseph Clarke and Joseph McKee – intimidation of Josephine Moan, BELF/1/1/2/68/9.

48 Deposition of Patrick McGurnaghan, 19 January 1922, PRONI, James Galbraith – shooting at Patrick McCunningham [sic], BELF/1/1/2/67/21.

49 Deposition of Minnie Parkes, 19 January 1922, ibid.

50 Deposition of Patrick McGurnaghan, 11 August 1921, PRONI, Thomas Saunders – shooting at Sarah Bannon, BELF/1/1/2/67/19.

51 Belfast Telegraph, 21 February 1922; Intelligence Officer, Fianna Belfast to Intelligence Officer, Belfast Brigade, IRA, 17 March 1922, PRONI, Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, HA/32/1/130.

52 Information form of Catherine Kearney, 25 August 1921, PRONI, George Harper – shooting at Catherine Kearney, BELF/1/1/2/66/11.

53 Deposition of Catherine Kearney (Senior), 5 September 1921, ibid.

54 Deposition of Catherine Kearney, 5 September 1921, ibid.

55 Belfast News-Letter, 31 October 1921.

56 Burke, Ghosts of a Family, pp63-64.

57 (Turtle) Statement of Lance Corporal R. Turner, Courts of Inquiry in Lieu of Inquests, Civilians – Alexander Turtle, Belfast, The National Archives, UK, WO/35/160/27, see https://search.findmypast.ie/record?id=IRE%2FWO35%2F160%2F00574&parentid=IRE%2FEAS%2FRIS%2F013266; (James) Belfast News-Letter, 25 November 1921 & 5 January 1922; (Lundy) Northern Whig, 17 February 1922 & Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p65; (Hazzard) Belfast News-Letter, 13 March & 5 April 1922. Two more Imperial Guards, David Cunningham and Walter Pritchard, were killed in Ballymacarrett on 22 November and 17 December 1921 respectively – for reports of Imperial Guards presences at their funerals, see Northern Whig, 28 December 1921 and Belfast News-Letter, 21 December 1921. Robert Beattie, killed in Ardoyne on 13 May 1922, was also identified as an Imperial Guard – see Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p178.

58 Belfast Telegraph, 10 March 1922.

59 Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 18 March 1922; District Inspector J. Dudgeon to Divisional Commissioner, RIC, 25 March 1922, PRONI, Rioting at funeral and looting of public house at Whitehouse, HA/5/176.

60 Irish Weekly and Ulster Examiner, 18 March 1922.

61 Ibid; this account was repeated when McAnaney’s widow lodged a claim for compensation – see Belfast News-Letter, 19 October 1922.

62 District Inspector J. Dudgeon to Divisional Commissioner, RIC, 25 March 1922, PRONI, Rioting at funeral and looting of public house at Whitehouse, HA/5/176.

Leave a comment