Acknowledgements

This is a project I have had in mind for a number of years but have only recently found time to complete. I should begin by acknowledging a number of inspirations.

The publication of the incredible Atlas of the Irish Revolution in 2017 first gave me the idea that the events of 1920-1922 in Belfast deserved a treatment like this.1

When the original “Dead of the Belfast Pogrom” article was published on The Irish Story in October 2020, a Twitter user named Stephen O’Neill used the accompanying database to create a map in Google Maps; he encountered some of the same problems I have described below.

In September 2024, the Military Service Pensions Archive created a Map of Six-County women applicants on their blog: this finally persuaded me to actually try to use Google Maps for this project.

Finally, and perhaps less obviously, the historian Tom Hartley has written a fantastic series of books on Belfast’s cemeteries, titled The History of Belfast, Written in Stone: these provide brief biographical details on a selection of the thousands of people buried in each cemetery.2

Creating the map

I would have preferred to use a 1920s map of Belfast as the basis for the project, such as the Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Historical Fifth Edition (1919-1963), which is available on the website of the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. However, I lack the computer skills to add markers to that map which, in any case, is under copyright. Instead, I have used the map of modern Belfast available in Google Maps. This created a number of challenges.

A combination of the Luftwaffe Blitz of 1941, successive rounds of urban redevelopment and the building of a motorway network have left many parts of Belfast unrecognisable compared to how they appeared in the 1920s.

Carrick Hill is a case in point. In April 1941, German bombs fell on Unity Street and Trinity Street. In 1968, the southern part of the area was completely flattened and redeveloped as the optimistically-named Unity Flats and the name “Carrick Hill” passed out of contemporary usage. In 1983, the Westlink motorway was extended to the north of Unity Flats, in the process obliterating Hanover, Dagmar, Cavour, Broadbent and Hartley Streets, all of which had previously had majority-unionist populations. Unity Flats was in turn demolished but was not replaced by the current housing until 2009, after which “Carrick Hill” returned to the lexicon. Although some of the area’s 1920s street names were revived, the modern equivalents don’t always follow the same path or even the same direction as the originals. Crucially, the Old Lodge Road, which formed a natural western boundary to the area in the 1920s, simply no longer exists.

In such cases – others include the Lower Falls and the entire area between North Queen Street and Corporation Street – I have used the Ordnance Survey 1919-1953 map as a guide to establish approximate locations for where vanished streets would be today if they still stood.

However, at the opposite extreme, zooming in on Google Maps allows individual house numbers to be identified: this means pin-point positioning of some markers is possible. For example, I have assumed that the 26 Bramcote Street in east Belfast on Google Maps is the same 26 Bramcote Street in which a Protestant man named Harry Little lived until 1922: he was killed outside his house on 11 July while trying to prevent the eviction of some of his Catholic neighbours.

In between these two extremes, where people were killed on a particular street but the inquest report did not specify exactly where on that street, I have simply spaced the markers evenly apart.

Using the map

At the top right-hand corner of the map is an icon showing the four corners of a rectangle: if you click on that icon, a full-size version of the map will open in a new tab. You can then zoom in or out, or move from left to right.

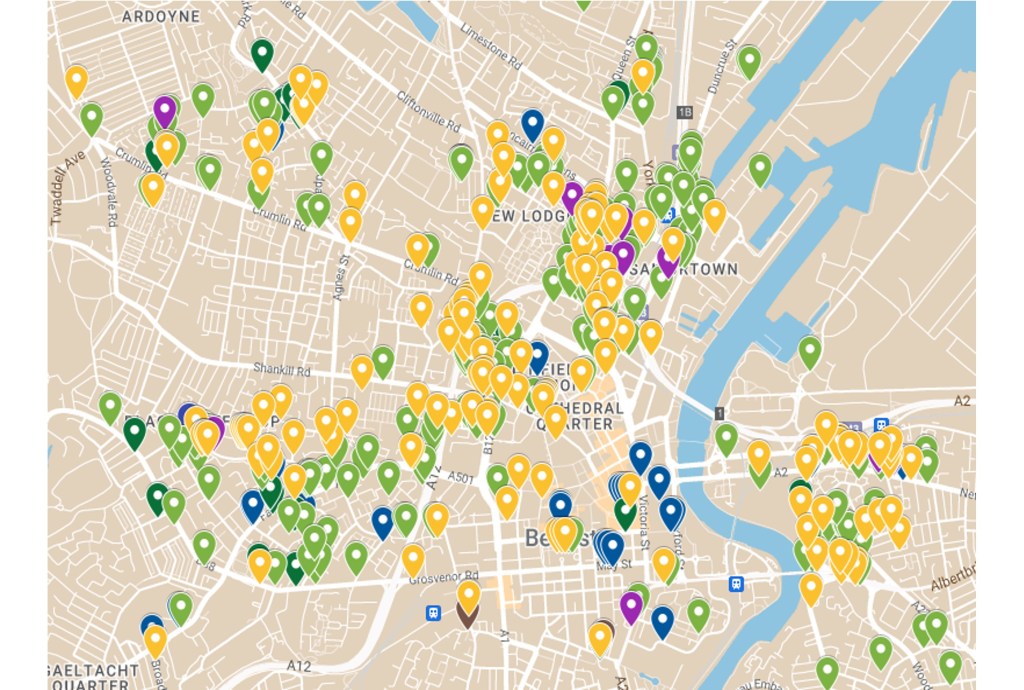

All those killed have been given colour-coded markers:

- Navy blue for members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), Royal Ulster Constabulary and Ulster Special Constabulary; this includes Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, who were members of the RIC3

- Brown for soldiers in the British Army

- Dark green for members of the republican combatant organisations, the IRA and Na Fianna Éireann; no members of Cumann na mBan were killed in Belfast

- Light green for non-combatant Catholic civilians

- Purple for members of loyalist combatant organisations: the UVF, Ulster Imperial Guards or Ulster Protestant Association

- Light orange for non-combatant Protestant civilians

Clicking on any marker will bring up a brief description of the individual in the left-hand panel. This shows the person’s name and the date on which they were killed. It also includes the organisation they belonged to, if any, and the circumstances in which they were killed e.g. during rioting, at close range, at the hands of a sniper, etc. The location at which they were killed is given as precisely as possible.

Where it can be established with a reasonable degree of confidence who, or which group, was responsible for a killing, this is stated. In many cases where the IRA carried out killings, the individuals involved either told the Bureau of Military History about it or they mentioned it in their application for a Military Service Pension.

In the case of killings by the police “murder gang,” IRA intelligence named the individual RIC members who they thought were responsible; these are listed as “IRA suspected…” Similarly, the police believed they knew the individuals responsible for some of the killings carried out by loyalists; these are also specified.

However, although some people were suspected of, and even charged with, particular killings, not a single person was convicted for any of the killings in Belfast in this period.

Where available, the inquest reports in the newspapers for each killing have been revisited. The relevant dates of these reports are also shown in the left-hand panel, using the following abbreviations: Belfast News-Letter (BNL), Belfast Telegraph (BT), Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner (IW&UE), Northern Whig (NW).

Some killings were not investigated by the City Coroner, but by military courts of inquiry; the verdicts of those courts were not always reported in the press. For these, the War Office file number is given; the original reports can be found in the Military Service & Conflict in Ireland section of findmypast.ie.

Finally, where a Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) file for an individual has been released, the file number is also shown, even if, as was particularly the case with a number of civilians, their relatives’ applications were unsuccessful.

Alternatively, if you click on a name in the left-hand panel, that person’s marker will appear in the centre of the map with a white disc around it, so you can see the location at which they were killed; all the above information relating to that person will also appear in the left-hand panel.

In conclusion, one of my abiding concerns throughout my research into the Belfast Pogrom has been to tell the individual stories of as many as possible of the people who died as a result of the political and sectarian violence. The vast majority were never remembered by anyone except their relatives and descendants: I call them “the people you never heard of.” Hopefully, this project will act as a memorial to them.

The blog post The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom – updated has been revised to reflect the additional research done for this project.

References

1 John Crowley, Donal Ó’Drisceoil & Mike Murphy (eds), Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork, Cork University Press, 2017).

2 Tom Hartley, Belfast City Cemetery (Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 2014); Milltown Cemetery (Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 2014); Balmoral Cemetery (Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 2019); More Stories from the Belfast City Cemetery (Maghaberry, BMF Business Services, 2024)

3 Although Harbour Constables were armed, they were not combatants in the normal sense. Two Harbour Constables were killed, one Catholic and one Protestant: they have been counted as civilians.

Leave a comment