Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

Control of the British Army

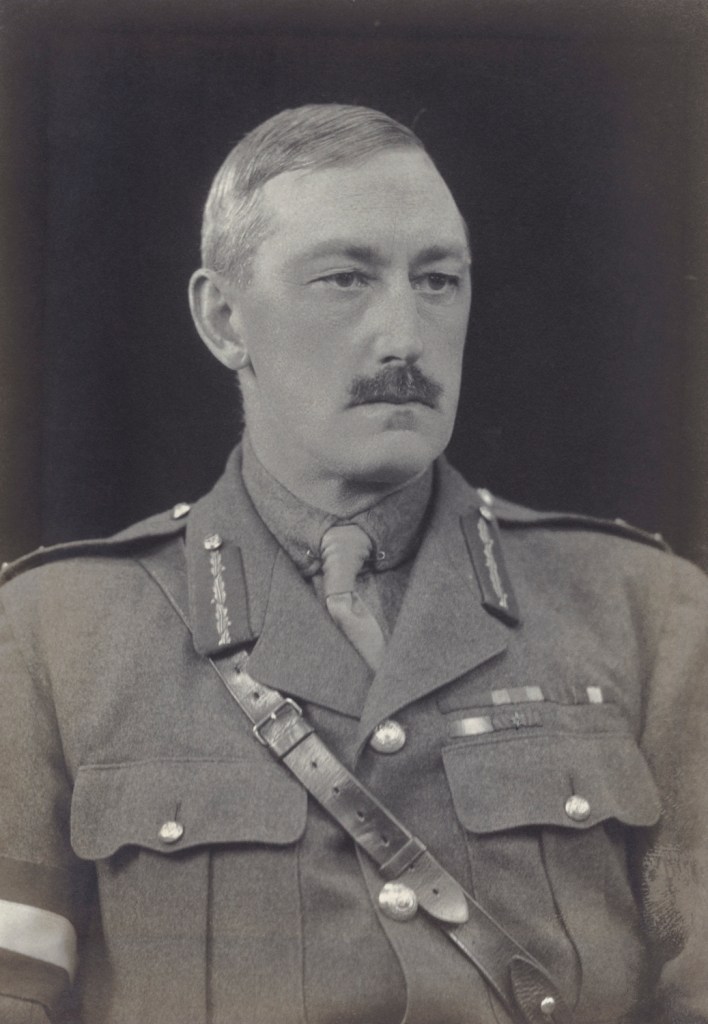

While British troops were being shot at on the streets, their overall commander, Major General Archibald Cameron, was dodging bullets in the background. He was the General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ulster District and his battle was against the Unionist government and revolved around control of the military.

In January 1922, around the same time that the general had identified “Protestant hooligans” as the biggest problem on the ground, the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates had highlighted the British Army’s freedom of action as a serious political problem for the Unionist government:

“…the military authorities can act entirely independently of the Northern Government, and so far as regards certain operations, have control over the police forces. This results in dual control. The troops and the RIC [Royal Irish Constabulary] are responsible alone to the Imperial Government while the Specials are responsible to the Northern Government.”1

The issue was that the drastic provisions of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act (ROIA) could only be exercised by the Competent Military Authority; when they did so, the police were automatically placed under their jurisdiction. Bates was planning to remedy this: “a bill is being drafted to enable the police authorities to use similar powers without having to fall back on the military authorities.” But it would take time to get the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Bill passed by the Northern Ireland Parliament.2

British soldiers searching for arms in Union St; only the military had the legal authority to use the provisions of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act

On 15 February, Bates wrote to the general to “urge upon you the necessity of supplying in full such troops as the police authorities require [emphasis added], particularly at the fixed points indicated.” Cameron replied that his brigade commander in Belfast “must retain independence of judgement as regards the best means of employing the troops.”3

A couple of days later, Bates tried a new approach, saying that mill-owners along the Falls Road were nervous after fixed military posts had been replaced by moving patrols, “leaving intervals when no military were in sight;” he warned that fresh outbreaks of violence during such intervals might leave the owners no choice but to shut the mills entirely, throwing people out of work. Cameron stood firm: “Troops will not be detailed to provide definite protection for individual persons or individual businesses.” Pointing out that there were now five battalions of troops in Belfast, he added, “There is no actual rioting going on in Belfast nor is there any organised resistance to the civil power. The troops are being employed on what is practically police duty.”4

At the beginning of March, Bates dragged the Divisional Commissioner of the RIC, Charles Wickham, into the fray. Wickham provided Bates with a report suggesting an escalation:

“I recommend that application be made to London for a direct instruction to be given to the military authorities that the troops are to be placed on duty on the streets in Belfast up to the numbers required by the police, and that they are to be retained on this duty so long as the police consider it necessary.”5

Wickham’s report included a barely-veiled threat: the alternative to the police issuing instructions to the military was to recruit an extra 1,000 members for the A Class of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) in country areas and draft them into Belfast, although “This force, owing to short training and the unavoidable party feeling, will not be as effective as military.” In other words, if Cameron wouldn’t put his troops at the disposal of the government, then the government would inflict more half-trained, sectarian, rural Specials on Belfast.6

Cameron refused to take the bait and dared Bates to bring the matter to London:

Major General Archibald Cameron, General Officer Commanding, Ulster District (© National Portrait Gallery, UK)

“I am not prepared to employ troops in the manner in which the Divisional Commissioner suggests nor to recommend such employment, and I cannot imagine the Imperial Government would consent to a manner of employing troops so inconsistent with regulations laying down the duties of troops in aid of the civil power.”7

His bluff called, Bates responded by simply asking for more troops to be sent into the city.8

RIC City Commissioner J.F. Gelston was the next to weigh in. Three policemen were killed by the IRA on the Falls Road over the course of three days in early March, as a result of which “Police work is at a standstill in this area. If they appear on the street they run the risk of being shot. The area…is practically in the hands of the IRA…Police work can only be carried out in Lancia armoured cars.” As well as twelve new fixed military posts and ten new patrol routes, he also wanted troops to take part in searches as directed by the local police District Inspector.9

When Wickham relayed this request, Cameron was unmoved: “The manner in which troops will be employed will be entirely at the discretion of the military commander and not at the discretion of the City Commissioner. This has been fully dealt with before…I cannot understand why it should only be possible for them to go about in Lancias.” The inference being that if his men could patrol on foot in groups, then why couldn’t the police?10

RIC City Commissioner J.F. Gelson claimed it was only possible for his men to patrol in Lancia armoured cars (Belfast Telegraph, 14 March 1922)

Bates made a speech to the Northern Ireland Parliament on 15 March in which he stated, “It was disgraceful to think that troops could not be brought out until citizens were shot down by the skilled members of the IRA…They had passed the stage of regulations for the use of troops.” After Cameron took exception to the criticism and complained to the northern Prime Minister, James Craig, Bates rapidly back-pedalled: “What I intended to convey, and which I hoped I had done, was that as far as you are concerned you had done everything possible to help us…May I again say how deeply I regret that you should have had any other impression than what I intended.”11

The general accepted the apology and pointed out “You cannot subdue disorder merely by defensive measures and scattering troops and police all over the place to reassure people.” He concluded with a subtle threat of his own: “I leave for England tonight to see Secretary of State for War.” That ended this particular battle.12

But while Cameron had sole access to the enhanced powers of the ROIA and was not answerable to Craig’s government, he lacked manpower. Although his men were drawn from a variety of regiments, these were not full regiments but a single battalion from each and even those battalions were under-strength. The area of operations of the 15th Infantry Brigade included Belfast, but in mid-March, its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Potter, was only putting an average of 521 men a day onto the streets.13

The British Army in Belfast were vastly outnumbered by the Special Constabulary – and everybody was aware of that.

British troops in west Belfast

The Norfolk Regiment were not the only British soldiers in Belfast to be attacked by loyalists.

Officers and men of 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders at their billet in Mackie’s Foundry on the Springfield Road (© PRONI, D3964/H/28; image used by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI)

The 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders was stationed in west Belfast. On 8 March, the same day that the Norfolk Regiment were being shot at by Specials in Carrick Hill, the Seaforths’ commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel H.F. Baillie, wrote to 15th Infantry Brigade:

“I wish to put forward a strong complaint against the attitude of a large number amongst the Special Constables, whose conduct in the past has not only been doubtful, but, in many cases, clearly obstructive, and which has made the work of our military patrols in maintaining order increasingly difficult.”14

He was no doubt angry after the shooting of one of his men two days earlier – they had repelled an attempted invasion of Clonard from the Shankill, in the course of which, a bomb was thrown from Canmore St at the edge of the Shankill into Cupar St, but caused no casualties. As loyalists fired back at the military, a Private Shepherd of the Seaforths was shot and wounded in the head.15

Baillie cited two other incidents on the same day: one of his officers had arrested a man named Robert Armstrong, but Armstrong turned out to be a station commandant of the Specials and so was released despite there being “very strong prima facie evidence against him of committing a serious crime.”16

That evening, a patrol of Seaforths on Cupar St saw three men loitering at the corner of Lawnbrook Avenue; the men attempted to run off but were caught and on John McLenaghan, they found a loaded revolver and a B Specials hat under his coat; he had no permit for the gun and was arrested.17

Soldiers of the Essex Regiment in Cork; after the Treaty, they were redeployed to west Belfast (© Imperial War Museum)

During the War of Independence, the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment had been based in Cork, where they were badly mauled by Tom Barry’s flying column of the IRA’s 3rd Cork Brigade. After the Treaty, they were transferred to the north as part of the general evacuation of British troops from the south, but as Cameron told Craig, even their own Commanding Officer (CO) doubted whether they could be neutral in Belfast, given what they had been through in Cork:

“The Essex Regiment has recently come up from Co. Cork, where their casualties numbered 60, including five officers murdered. The CO told me when the battalion first came up that their indignation was so great that it would be difficult for them to be impartial between the two sides. It is already being accused of being pro Sinn [Fein].”18

Two reports written by the same officer on the same day illustrate this.

On 26 March, Captain J.M. Dacre of the Essex Regiment reported threats made by Specials against his men:

“Two of the chief offenders in this respect have been (1) Special Constable Dremner of College Square, No. 11 Police Barracks and (2) Special Constable Thompson of No. 11 College Square Barracks, the latter having caused a great disturbance and in front of a large crowd openly denounced the NCO as a marked man. This same NCO has also been warned by Special Constables in uniform, on duty, that he had better look out for himself as he is a marked man.”19

Later that evening, Dacre went to investigate the shooting of a Catholic shopkeeper at the junction of Albert St and Quadrant St in the Lower Falls. At the time, there were a number of streets between Albert St and the bottom of the Grosvenor Road (adjacent to the present-day police station), the population of which was 85% Protestant; IRA intelligence reported that eight men from Elizabeth St alone were members of the Specials.20

During a follow-up search in nearby Selina St, Dacre found a Martini Henry .303 rifle in the possession of B Special Sergeant J. Armstrong; the local RIC District Inspector confirmed that “the man had no right whatever to have a rifle in his house, that the rifle we had found was not of service pattern and asked me to detain him;” Armstrong was arrested.21

Just then, further firing erupted further up Albert St in the vicinity of Raglan St; in a foreshadowing of events almost 50 years later, Dacre reported:

“…the trouble began, and the deaths and wounded originated through the cars of Special Constables firing indiscriminately upon crowds down side streets, from the main streets as they passed by…in fact women were handing out cigarettes to the troops and imploring them to protect their homes from ‘the murderers.’”22

Afterwards, as his men made their way back to their billet, Specials opened fire on them:

“On the return to Roden Street Barracks, one of our patrols were fired on by three men from corporation yard off Willow Street and they returned fire, with what result is not known. The NCO in charge has since reported to me that some Special Constables had met the patrol with a large number of civilians, and had accused him of firing upon them, and wounding one of their number, a Special Constable, adding ‘You Essex are a damned nuisance and we will get our own back before long.’”23

But Dacre’s misery for that day was not yet complete – more bad news arrived while his report was still being typed so with a frustrated howl, he departed from the conventional reserved formality of military reports by concluding: “I have, since writing the above report, been informed over the phone that the Divisional Commissioner, RIC has ordered the release of Sergeant Armstrong, B Specials RIC, on what grounds I have no idea.”24

British soldiers continued trying to rein in loyalists: on 5 April, republican intelligence reported that “Military officer at Conway Street stops and orders two cages of Specials off Falls Road.” Three days later, a group of Catholic boys playing football near the Springfield dam were fired at: “A unionist named Roberrt Laird was caught by a squad of Seaforth Highlanders who rushed on the scene. Revolver with ten rounds of ammunition found on him.”25

The 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment were also drafted into west Belfast. On 14 May, the Provisional Government in Dublin received a report that “A soldier of Cheshire Regt walking down Townsend St was shot at from Shankill Road end of Townsend St (Protestant area). Bullet grazed his coat. Taken for safety into Catholic house.”26

Just under three weeks later, on 2 June, soldiers from the same regiment on duty at Brickfield Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Barracks, at the junction of the Falls Road and Dover St, thought they had come under fire from the direction of the Shankill; they returned fire. Thirty-eight Protestant residents of Dover St signed a joint letter to Bates, complaining that the soldiers had been drunk: “We think it an outrage that the sons of Ulster come home from fighting Prussian militarism to suffer the ravages of British militarism…use your influence in having the soldiers replaced from this locality and replaced by Specials as we think the soldiers are our enemies.”27

British troops in east Belfast

The night after the Norfolk Regiment’s Private Barnes was killed by a loyalist in north Belfast, that incident was almost replicated in east Belfast.

British soldiers at the junction of the Newtownards Road and Seaforde St (The Graphic, 1 October 1921)

On the night of 3 January, a detachment of the Royal Artillery Mounted Rifles had just relieved Somerset Light Infantry manning a permanent military post outside St Matthew’s church on the Newtownards Road. They heard the noise of a bomb exploding and shooting coming from further in towards the river, from Foundry St, and were moving to investigate when they were fired at by a group of men standing at the corner of Fraser St, behind them to their right. According to Lieutenant S.J. Livingstone-Leasmouth, the first shot:

“…was followed by a second shot from the same group, aimed straight at my party. This shot passed between a sergeant and myself, who were standing about 5 feet apart. The group began to break up immediately this second shot was fired and my party returned the fire simultaneously. About five men were seen to fall. There were no civilians in the vicinity at whom the group could have been firing. They could only have aimed at us.”28

A loyalist named Alexander McCrea was killed when the military returned fire. Nothing is known of his affiliations – he may have been a member of the Ulster Imperial Guards or the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), an east Belfast paramilitary group; he may also have been a member of the C1 Specials. But just like the Imperial Guard Alexander Turtle in Sailortown the previous day, he attempted to kill a British soldier only to end up being killed by one.

On 19 April, a report by the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee stated, “Military in Ballymacarrett area forced to retire from fire of the Orange mob.” In their absence, that day alone, four Catholics and two Protestants were killed in the area; three more died the following day – a member of the IRA and two more Catholic civilians.29

Some weeks later, Cameron complained to Craig of an incident in the same area in which “an officer of the same regiment [Somerset Light Infantry] was knocked down and assaulted by a Protestant crowd; being of exceptional physique and activity he managed to regain his feet and wound one of his assailants, or he might have been murdered.”30

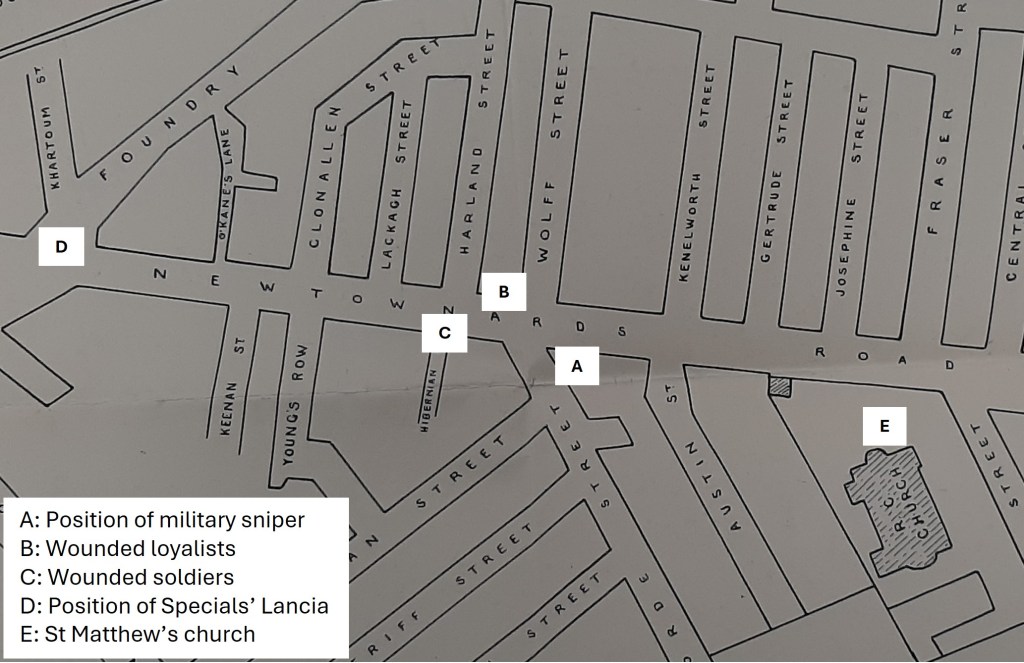

On 3 June, another clash took place on the Newtownards Road which escalated all the way to London.

The area of the Lower Newtownards Road around Seaforde St (map © PRONI, BELF/1/1/2/68/7; reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI; legend added)

A sniper from the Somersets, stationed in a derelict house, saw Daniel Bruce emerge from Harland St with a rifle and fire a shot down nationalist Seaforde St; the sniper shot and wounded Bruce and when Bruce’s companion, Samuel Millar, picked up the rifle, the sniper also shot and wounded him.31

Hearing the shooting, a sergeant and three privates from the Somersets came to investigate. As they neared Seaforde St, a large group of loyalists emerged from Wolff St, one of whom was carrying a revolver – he shot and wounded Sergeant George Mitchell and Private Henry Burrows; Burrows was hit in the back and arm, so the shots were not intended to incapacitate, but to kill. The loyalists then set upon and beat both the wounded and the unwounded Somersets, stealing three men’s rifles.32

Meanwhile, a Specials Lancia armoured car which had been stationed at the bottom of Foundry St also drove up. Believing the sniper’s shots to have been fired by nationalists, they followed what was evidently their normal practice and raked Seaforde St with machinegun fire. They then reversed back along the Newtownards Road, passing within twenty yards of the wounded soldiers, who they assumed were being aided by friendly and anxious unionists rather than being attacked by hostile and angry loyalists. They said they thought the soldiers were wounded by shots from the nationalist O’Kane’s Lane, so they also machinegunned that street for good measure.33

When news of the afternoon’s events reached Winston Churchill, chairman of the UK cabinet’s Irish Committee, he was livid and demanded that Craig “make an example of the Special Constabulary in the armoured car.”34

No such action was taken. An investigation by the RUC’s District Inspector R.R. Hegarty concluded that the Specials had made a genuine mistake. The two wounded loyalists, Bruce and Millar, were not charged, on the basis that the only evidence against them was that of the soldier who had shot them; this was somehow viewed as insufficient.35

The only person who faced any consequences from these shootings was Joseph Arthurs. He was identified by Private Francis Marks, who had been stationed in the grounds of St Matthew’s church, as having been the man who emerged from Wolff St with a revolver to shoot the Somersets’ sergeant and private. Arthurs was charged with the attempted murder of the two soldiers but despite the eyewitness identification by Private Marks, was found not guilty. However, the RUC viewed him as “probably the worst gunman on the Newtownards Road” and regardless of his acquittal, continued to believe in his guilt: “No doubt he was the right man.” He was interned in October.36

Summary and conclusions

The unionist regime in Northern Ireland is often portrayed as an invincible, omnipotent monolith – but for most of the first year in which Craig’s government was in office, it was very far from that. The British Army’s misfortune was that it found itself at the point of convergence between several factors which weakened that government’s ability to control and manage the security response to the IRA.

The first of these was the brittle nature of the ties between the government and some of its supporters.

The Belfast General Strike of 1919 had provided a chilling warning to political unionism that its working-class followers could exercise their agency in other directions that were less to its liking. It remained apprehensive of losing their allegiance and even in 1921 and 1922, jumped nervously any time mutterings of discontent or grievance arose from the Shankill, Old Lodge Road or York St.

In his speech on the Twelfth in 1920, Edward Carson had warned the British government that “if, having offered you our help, you are yourself unable to protect us from the machinations of Sinn Fein, and you won’t take our help; well, then, we tell you we will take the matter into our own hands.” The Pogrom that followed showed the alacrity with which loyalists could take matters into their own hands.37

The formation of the Special Constabulary thus served a dual purpose. It provided a means for political unionism to maintain the loyalty of its working-class base and, by channelling their energies in a sectarian direction, gave it a more dependable means of combatting the nationalist enemy within than the RIC, which it viewed with distrust. The fact that the Specials went about their task using methods which even Craig conceded were “unorthodox” was not an issue.

But by demobilising the B Specials, the Truce let the loyalist genie back out of the bottle, creating space for the remobilisation of the UVF and the growth of newer groups like the Imperial Guards and the UPA; by November 1921, loyalist agency was firmly on the march again. Craig and Bates sought to recapture the multiplying genies in a new bottle marked “C1 Specials,” but that formation would need time to be trained – however perfunctorily – and armed. In the meantime, the intended recruits had already established their independence of action and were already armed.

The second problem for the Unionist government was that the British Army took its orders from London, not Belfast.

The Truce left Craig and Bates beholden to the military, who had no intention of behaving like Specials in khaki, as unionists in and out of government expected them to do. The Specials’ purpose was to suppress the IRA; the British Army’s purpose was to suppress disorder, regardless of the source of that disorder.

But it also had the sole ability to exercise the provisions of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act. It took several months of mounting unionist frustration at the military’s unwillingness to deploy those provisions at their behest, rather than as the Competent Military Authority saw fit, before Craig and Bates decided to embark on the journey towards the Special Powers Act. After April 1922, they finally had the repressive legal arsenal they had jealously craved and so had less need of the military – the Specials could exercise the provisions of the new Act as Bates ordered.

The full remobilisation of the B Specials after 22 November 1921 emboldened loyalists, but the signing of the Treaty just over a fortnight later, complete with its Boundary Commission clause, renewed their feelings of apprehension: to them, it looked like a surrender to republicans. Their resulting distrust of the British government extended to the British Army.

It was these resurgent, armed, yet fearful and resentful loyalists that Cameron identified as the main threat to order in early 1922. The military’s dogged determination to maintain strict impartiality and, if need be, stand between loyalists and their intended Catholic victims was seen as a provocation by the B Specials, C1 Specials, Imperial Guards and UPA. In those circumstances, armed conflict between the military and loyalists was inevitable.

The Norfolk Regiment was certainly on the frontline of that conflict, both around York St and in Carrick Hill. But the fact that similar attacks were also made on soldiers from the Seaforth Highlanders, Essex Regiment, Cheshire Regiment, Royal Artillery Mounted Rifles and Somerset Light Infantry in other parts of the city suggests that it was the role played by the British Army in general, rather than the local presence of a particular regiment of that army, that prompted loyalist violence against them.

By the end of May 1922, the Unionist government’s British Army mini-crisis had passed.

The military policy of impartiality was simply no longer relevant as they were outnumbered and easily bypassed by the various official and unofficial loyalist forces who were, by then, on the rampage. Political unionism very definitely approved of those forces’ direction of travel, so all was well again within the unionist family.

The passing of the Special Powers Act meant that the Specials now had draconian legal powers to augment their cruder extra-legal inclinations.

For all of Roger McCorley’s protestations that “As far as we could help it we didn’t attack the British,” an unintended consequence of the IRA’s Northern Offensive was that it suddenly drew the British Army’s focus to the border and its main priority then became securing Northern Ireland against the prospect of invasion from the south. That meant that after the Battle of Pettigo and Belleek, the military were viewed in a much more benign light by unionism.

It also left Belfast’s Catholics to fend for themselves.

References

1 Minister of Home Affairs to Cabinet Secretary, 9 January 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Disturbances in Belfast, CAB/6/37.

2 Ibid.

3 Minister of Home Affairs to General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ulster District, 15 February 1922 & GOC, Ulster District to Minister of Home Affairs, 16 February 1922, PRONI, Military aid to civil authorities in Northern Ireland, HA/32/1/260.

4 Minister of Home Affairs to GOC, Ulster District, 18 February 1922 & GOC, Ulster District to Minister of Home Affairs, 20 February 1922, ibid.

5 Divisional Commissioner to Minister of Home Affairs, 5 March 1922, ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 GOC, Ulster District to Minister of Home Affairs, 7 March 1922, ibid.

8 Minister of Home Affairs to GOC, Ulster District, 10 March 1922, ibid.

9 City Commissioner to Divisional Commissioner, 16 March 1922, ibid.

10 GOC, Ulster District to Divisional Commissioner, 17 March 1922, ibid.

11 Belfast News-Letter, 16 March 1922; GOC, Ulster District to Prime Minister, 20 March 1922 & Minister of Home Affairs to GOC, Ulster District, 28 March 1922, PRONI, Military aid to civil authorities in Northern Ireland, HA/32/1/260.

12 GOC, Ulster District to Minister of Home Affairs, 29 March 1922, ibid.

13 Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Potter to his mother, 19 March 1922, Princeton University Library Special Collections, Herbert Cecil Potter papers.

14 Officer Commanding (OC), 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders to HQ 15th Infantry Brigade, 8 March 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

15 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 11 March 1922.

16 Captain D.B. Aitken to OC A Company, 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, 7 March 1922 & Colonel-Commandant Commanding, 15th Infantry Brigade to HQ Ulster District, 28 March 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

17 2/Lieutenant G.P. Murray to OC A Company, 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, 7 March 1922, ibid.

18 GOC, Ulster District to Prime Minister, 28 March 1922, ibid.

19 Captain J.M. Sacre to Major R.N. Thompson, 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment, 26 March 1922 (first report), ibid.

20 https://census.nationalarchives.ie/search/; List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes, July 1922, in List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th 1922, Military Archives, Historical Section Collection, HS/A/0988/15.

21 Captain J.M. Sacre to Major R.N. Thompson, 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment, 26 March 1922 (second report), PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Reports for 5 & 8 April 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland outrages Jan-Oct 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

26 Report for 14 May 1922, ibid.

27 Samuel Parkes et al to Minister of Home Affairs, 3 June 1922, PRONI, Residents of Dover St, Belfast: letter complaining of the conduct of the military, HA/5/968.

28 Statement of Lieutenant S.J. Livingstone-Leasmouth, Courts of Inquiry in Lieu of Inquests, Civilians – Alexander McCrae, Belfast, The National Archives (UK), WO/35/154/31; available at https://search.findmypast.ie/record/browse?id=ire%2fwo35%2f154%2f00234

29 Report for 19 April 1922, National Library of Ireland, Art Ó Briain Papers, Correspondence between C.B. Dutton and the Belfast Catholic Protection Committee, Ms 8,457-12.

30 GOC, Ulster District to Prime Minister, 6 June 1922, PRONI, Friction between military forces and Ulster Special Constabulary, CAB/6/43.

31 Statement of evidence in the case of wounded gunmen Daniel Bruce and Samuel Millar, 28 June 1922, PRONI, File relating to the wounding of Daniel Bruce and Samuel Millar by a military sniper, HA/5/255.

32 Depositions of Sergeant George Mitchell & Private Henry Burrows, both 27 June 1922, PRONI, Joseph Arthurs – shooting at George Mitchell and Henry Burrows, soldiers of the 1st Battalion Somerset Regiment, BELF/1/1/2/68/7; District Inspector R.R. Spears to City Commissioner, 6 June 1922, PRONI, Complaints by military against police for refusing to come to their assistance at Foundry St, Belfast, HA/5/972.

33 Statement of Special Constable John Faris, 6 June 1922, PRONI, File relating to the wounding of Daniel Bruce and Samuel Millar by a military sniper, HA/5/255.

34 Secretary of State for Colonies to Prime Minister, Northern Ireland, 6 June 1922, PRONI, Friction between military forces and Ulster Special Constabulary, CAB/6/43.

35 District Inspector R.R. Hegarty to City Commissioner, 12 June 1922, PRONI, Complaints by military against police for refusing to come to their assistance at Foundry St, Belfast, HA/5/972; City Commissioner to Inspector General, 25 July 1922, PRONI, File relating to the wounding of Daniel Bruce and Samuel Millar by a military sniper, HA/5/255.

36 Deposition of Private Francis Marks, 27 June 1922, PRONI, Joseph Arthurs – shooting at George Mitchell and Henry Burrows, soldiers of the 1st Battalion Somerset Regiment, BELF/1/1/2/68/7; PRONI, Arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289A.

37 Belfast News-Letter, 13 July 1920.

Leave a comment