Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

Introduction

In his statement to the Bureau of Military History, the commander of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, Roger McCorley, noted that during the period when the Truce was supposed to be in effect, “…a new factor made its appearance. This was a hostility between the British military, especially the rank and file, and the Special Constabulary and on several occasions British troops opened fire on ‘B’ class Specials who were attacking the nationalist areas.”1

McCorley attributed the hostility to British soldiers’ jealousy of the higher rates of pay enjoyed by the A Class of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC or “Specials”); he even claimed that on one occasion, when an IRA unit were planning to attack a Specials’ supply lorry, the sergeant in charge of a nearby military patrol told them, “We are moving off now and you can do what you like with the ———.”2

When discussing the May 1922 Northern Offensive with Ernie O’Malley, McCorley made a very curious statement: “As far as we could help it we didn’t attack the British.”3

Although he explained the animosity between British troops and the Specials as being related to pay grievances, McCorley was being disingenuous: the IRA leadership in Belfast were well aware of the real reasons for the tensions. In February 1922, the Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, Frank Crummey, told Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy that “Information has been received that an attempt is to be made by Orange gunmen to a shoot a soldier of Norfolk Regiment as a reprisal for Hugh French a ‘B’ Special shot by military.”4

The British Army in Belfast

The role played by the British Army in Belfast was very different to the one it played elsewhere in Ireland. In other areas, it acted alongside the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in directly combatting the IRA, with parts of the country placed under martial law, but in Belfast, its primary function was to act as an “aid to the civil authorities” in suppressing disorder. In practice, this meant that when rioting or shooting broke out which the police were unable to control, they would request assistance from the military.

At a senior level, the British Army had a dismissive view of the police, both the RIC and the Specials. Belfast lay in the area of operations of the 15th Infantry Brigade – in 1922, its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Potter, wrote in a letter,

“Between ourselves the police are perfectly useless…The fact of the matter is that no-one in the north of Ireland is fit to be a policeman…the result of all this is that there is an incessant shout from the population for soldiers to be put on the streets. That is not our job…If a man is murdered or a till robbed in London, you do not call out the Brigade of Guards.”5

Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin have noted that:

“It is clear that in Belfast the military did not generally distinguish between contending groups of rioters or curfew breakers on political lines: they would fire impartially on crowds failing to disperse, or on curfew breakers or on anyone who failed to halt when ordered to do so, or in response to fire aimed at them.”6

British troops facing both directions in York St, scene of some of the worst violence

In short, British troops suppressed disorder by doing what they had been trained to do – they shot whoever they felt needed to be shot at the time.

Owing to the illness of his predecessor, Lieutenant Colonel George Carter-Campbell, Potter had assumed command of 15th Infantry Brigade at the start of January 1922; within weeks of arriving, he had concluded: “I think the Sinners look upon us as their defence against extermination for the Orangemen would blot them out entirely one of these days if seriously provoked.”7

Over the course of the Pogrom, British troops killed 54 people in Belfast. When those figures are broken down, it is easy to see why the British Army was less than loved by some of the city’s unionist population.

Thirty-four of those killed by the military, or 63%, were unionists: twenty-eight Protestant civilians, three members of the Specials and three other loyalist combatants. This contrasted with a figure of nineteen nationalists, or 35% of the total – sixteen Catholic civilians and three members of the IRA. The final killing by a soldier was of another soldier in a “friendly fire” incident.

The 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment was definitely responsible for twenty-one of the British Army killings; it was also very likely responsible for a further six, largely based on which units are known to have been in action in particular areas at particular times. Fifteen other killings were spread across nine different regiments and the specific regiment responsible was not identified at the inquests into the remaining twelve killings. This meant that the Norfolk Regiment alone was responsible for half of all British Army killings; in addition, 74% or just under three-quarters of the people it killed were unionists. It is therefore little wonder that, as Tim Wilson has concluded,

“In attempting to implement a relatively even-handed policy of suppressing sniping from whichever side seemed to offer the most urgent threat at the time, the Norfolks fundamentally offended popular loyalist perceptions of where the responsibility for the conflict lay. The Norfolks refused to project the guilt unilaterally onto the Catholic areas. In doing so, and in opposing Protestant communal defenders, they challenged the basic loyalist understanding of the conflict in which they found themselves.”8

This sowed the seeds for considerable animosity to be directed by unionists at the Norfolk Regiment in particular.

Losing the Specials

While McCorley dated the breakdown in relations between loyalists and the British Army to the signing of the Truce in July 1921, the Truce was not the cause of the problem – rather, the Truce threw into sharp relief a deeper political issue already facing the Unionist government.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 provided for the establishment of separate Parliaments and Governments of Northern and Southern Ireland, which would be responsible for maintaining law and order in their respective areas. The northern parliament had its inaugural meeting on 7 June and James Craig became Prime Minister of its first government. But it was a government without a police force.

There was a major stumbling block in the way of it having one: on 23 June, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Hamar Greenwood, said that “it would not be possible to transfer the police to the Northern Government until their transfer had been arranged for the southern area.”9

The problem was that there was no corresponding Government of Southern Ireland to which policing powers could be transferred. Although a general election had been held in the south on 24 May, returning 124 Sinn Féin and 4 Unionist candidates unopposed, Sinn Féin treated this as an election for the second Dáil Éireann. The Unionist MPs did in fact meet for a state opening of the Parliament of Southern Ireland on 28 June: they simply elected a speaker and then adjourned indefinitely.

The RIC in Northern Ireland, including the Specials, therefore continued to report to the Chief of Police of the British administration in Dublin Castle, General Hugh Tudor. Unionists distrusted the rank and file of the RIC – according to the Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates,

“During the disturbances in the South of Ireland large numbers of the better type of man were drafted to the south and men who could not be trusted or who were inefficient were sent into Belfast. Over 50 per cent of the force in the city are Roman Catholics, mainly from the South, and many of them are known to be related to Sinn Fein.”10

The Specials, almost exclusively drawn from the local unionist population, were far more preferable to Craig’s government. But the arrival of the Truce robbed Craig and Bates of their Specials.

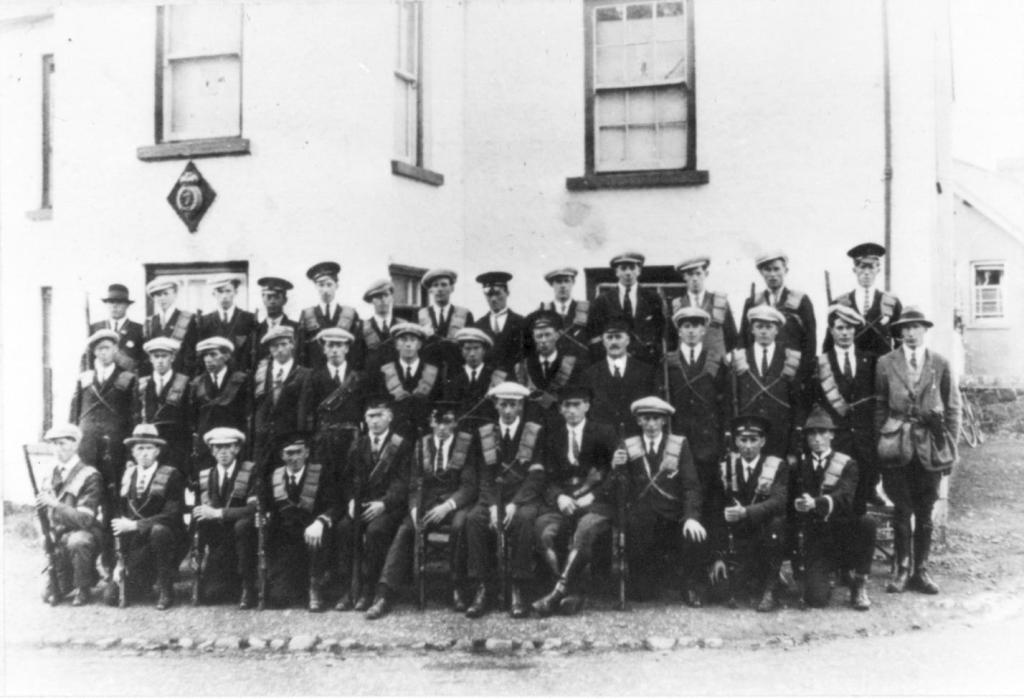

B Specials in Rasharkin, Co. Antrim; the B Specials were demobilised under the Truce

On 10 July, Tudor informed the RIC Divisional Commissioner in Northern Ireland, Charles Wickham, about the Truce – Wickham instructed his subordinates accordingly: “From midday 11th all police action to be confined to civil duties – to be unarmed except in emergency and then only by power of County Inspector. No men off duty to leave their barracks armed. From same hour, all Class ‘B’ patrols are suspended.”11

The A Specials would continue to operate alongside the regular RIC but subject to the same constraints. The reason why the B Specials were singled out for demobilisation may lie in the fact that, according to historian Edward Burke, “British officials arrived at an uncomfortable conclusion: the police, specifically the ‘B’ Class of the Special Constabulary, were instigating rather than suppressing sectarian violence.”12

In Belfast, the Truce was stillborn: an IRA ambush on an RIC patrol in Raglan St on the night of 9/10 July, in which a police constable was killed, prompted intense rioting in west Belfast, with attacks by loyalists and Specials on nationalists along the Falls Road. “Almost immediately after the outbreak of rioting, [RIC City] Commissioner Gelston requisitioned troops, but Carter-Campbell refused to intervene, reckoning that the civil authorities should be able to handle the situation.”13

The British Army felt hamstrung by the Truce; its General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ireland, General Neville Macready, told Bates: “…my instructions [to] Col Commandant 15th Brigade are that so far as troops are concerned they will be guided by the spirit of the agreement entered into for the cessation of hostilities.” In practice, this meant that all military and police raids would cease, military operations would be restricted to supporting the police in their civil duties and curfew restrictions would be lifted.14

Lieutenant Colonel George Carter-Campbell, was instructed to “be guided by the spirit of” the Truce

Craig argued with Greenwood that the Truce had been conceived in response to the situation in the south, but that the north was unique and demanded unique measures – in particular, the remobilisation of the Specials:

“I think it probable that the authorities in Dublin have failed to realise that the situation in Ulster is different from that obtaining in the rest of Ireland, and requires a different form of treatment. There is a general feeling of uneasiness among certain sections here, caused by the putting out of action of the Special Constabulary.”15

Intense sectarian violence flared up again around York St and in Carrick Hill at the end of August, with twenty-two people being killed in just three days. O’Duffy had recently arrived to become the Truce Liaison Officer for Ulster – he ordered the IRA to provide a robust response to the latest attacks, leading to unionist accusations that IRA reinforcements had been drafted in from outside Belfast. Unionists also wanted strong action by the British government: “Three measures were demanded: a significant display of military force; the calling out of the Special Constabulary; and the full use by the Crown forces of their powers under the ROIA [Restoration of Order in Ireland Act], in particular the powers of isolated search, arrest and internment.”16

In response to the outbreak, the Northern Ireland Government met three times in 24 hours over 31 August – 1 September. At the first meeting on the morning of 31 August, Gelston was “more inclined to think that men from other localities in Belfast with rifles had been concentrated in the disturbed area,” rather than extra IRA being sent into the city from elsewhere. Carter-Campbell remained confident that he had enough troops to manage the situation.17

The second cabinet meeting that evening was joined by the Assistant Under-Secretary for Ireland, Alfred Cope, and by Tudor. Cope said the ROIA remained in force and could be used, but in relation to the Specials, he was adamant: “Mr Cope emphatically stated that the Special Constabulary could not be considered as available for duty in the Catholic quarters of Belfast and he was prepared to put this in writing. To draft the Special Constabulary into the disturbed area would be equivalent to putting petrol on the fire.” Instead, Carter-Campbell promised to send another battalion of troops into Belfast.18

Before the reconvened meeting the following morning, Cope met the Catholic Bishop of Down & Connor, Joseph McCrory, and the Unionist MP for North Belfast, William Grant. He heard that their respective followers were equally “terror-stricken” and begging for protection: “Both sides seemed to be in a state of insecurity and both sides were shooting…As regards the power of internment, Mr Cope suggested that both sides would have to be interned as both sides were shooting.” After this unsubtle warning, unionists quickly stopped clamouring for internment.19

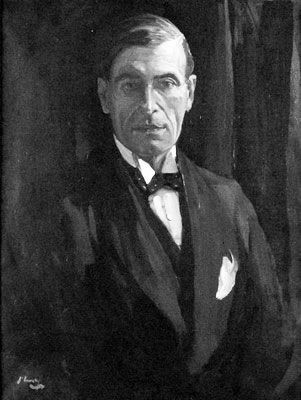

Alfred Cope: remobilising the B Specials “would be equivalent to putting petrol on the fire.”

In the following weeks, Bates and Craig came under pressure from their grassroots supporters. Grant “introduced” a delegation to them at meetings on 7 and 12 September respectively: it consisted of two former army captains, accompanied by “Comrade Turner” and “Comrade Blair.” These men “offered the services of upwards of 300 ex-servicemen from Workman and Clark’s [shipyard] for the purpose, as they stated, of defending their homes.” Craig thanked them for the offer but cautioned against “an inclination to be what he might describe as ‘ultra loyal.’” Instead, he suggested they form “watch committees” which could alert the police and troops of any fresh outbreaks of violence, as well as restraining the urge to retaliate.20

Carter-Campbell was determined that such committees would not be a back door for remobilising the B Specials. He was only prepared to tolerate them if they were not self-appointed but selected by police District Inspectors, would not operate during curfew hours, would not be armed and would operate only in their own areas and “only to control those of their own political and religious views.”21

Feeling vulnerable in the absence of the Specials, unionists started becoming more critical of the British Army.

Later that month, two separate complaints about the conduct of the military landed on Carter-Campbell’s desk. On 13 September, Bates relayed a complaint by David Fee, a B Specials commandant in west Belfast; Fee said that three days previously, a corporal and other soldiers had smashed in the front doors of six families living in Malvern St off the Shankill Road, struck residents and even threatened to “knock the brains out of an invalid girl in bed.” In one particularly unfortunate turn of phrase, a man claimed to have been called an “Irish swine” by a soldier – the resident’s name was William Ireland. Four days later, Fred Crawford claimed that drunk soldiers from the Norfolk Regiment had abused unionists living in Trafalgar St in Sailortown, shouting “Up the rebels” and “We won’t leave an Orange bastard about York Street.” Crawford also claimed that a young man had been bayonetted at his own front door for no reason.22

Nelson St in Sailortown; unionists in nearby Trafalgar St claimed that Norfolk Regiment soldiers had abused them

Carter-Campbell became ill, so in his place, Lieutenant Colonel A.H. Yatman conducted the enquiry into the Malvern St incident; he found “the claims of the inhabitants to be greatly exaggerated.” A full military court of enquiry was scheduled to investigate the Trafalgar St accusations; Bates was invited to attend, along with any witnesses who could substantiate the allegations – he declined. After the court of enquiry had met, identical letters were sent to Bates and Crawford, telling them “I am satisfied that the troops carried out their difficult duties in a satisfactory manner, and that the complaints made against them are unfounded.”23

Meanwhile, Craig continued to advocate for the remobilisation of the B Specials and in late September won a partial, though hugely significant, concession by Dublin Castle. Tudor informed Wickham that:

“…the Government will not oppose the calling out of B Specials in Belfast district alone, provided that their employment is restricted to the protection of Protestant areas, and prevention of outbreaks of rowdy elements of the Protestant side, and that the patrolling of Catholic areas continues to be entrusted solely to the military and regular RIC.”24

However, any impulse towards jubilation in unionist circles was tempered by a parallel telegram from Greenwood: “It must be understood that in such areas as are under military control the Specials will be under the military for all tactical purposes.” Carter-Campbell promptly notified Wickham that he would take over control of both the regular police and Specials in Belfast from 30 September.25

With the B Specials now partly remobilised, Craig’s focus shifted towards their numbers – he tried to persuade Macready that a recruitment drive was necessary to replace the natural wastage that had occurred during the Truce; he concluded with a remarkable piece of understatement: “The Special Constabulary are sometimes a little unorthodox in their methods but are extremely trustworthy and fear nothing.”26

The two met in Belfast on 20 October, with Macready taking the opportunity to introduce Craig to the British Army’s new GOC, Ulster District, Major General Archibald Cameron.

The main focus of the meeting was the potential for a breakdown in the Treaty negotiations in London: all were agreed that this would lead to a resumption of IRA activities, which in turn would require the imposition of martial law across the whole of Ireland. Craig argued that enforcement of martial law in Northern Ireland should be led by the Specials, particularly the A Specials, who were “of a more military character.” Macready voiced concerns about the re-emergence of the UVF but Craig pointed out that this was the British government’s fault as it had suspended recruitment to the B Specials; however, “he thought there would be no difficulty in this matter if time were given by the authorities to enable all well disposed respectable individuals to serve the Crown in some way.”27

Craig felt the A Specials were “of a more military character”

Restoring the Specials

November 1921 proved to be a pivotal month.

On 7 November, Craig, accompanied by his Cabinet Secretary, Wilfrid Spender, travelled to London to meet the Secretary of State for War, Laming Worthington-Evans, who was a member of the British delegation to the Treaty negotiations, and the supreme commander of the British Army, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshall Henry Wilson.

Their shared assumption was that the Treaty talks would break down; the meeting decided that in this event:

- Martial law would not be applicable in Northern Ireland

- Craig’s government would be responsible for maintaining law and order in the north

- Apart from those guarding IRA internees at Ballykinlar Camp, all British troops would be withdrawn from Northern Ireland three days after the breakdown but would “hold the boundary outside Ulster getting into touch with the local Ulster force on the boundary.”

- “The Government of Northern Ireland undertook to raise all the necessary forces for general protection within its own boundaries. These would take the form of Special Constabulary.”28

Two days later on 9 November, the British government decided to go ahead with the transfer of responsibility for law and order to Craig’s government and he was advised that this would take effect from 22 November.29

However, on the same day, Wickham jumped the gun somewhat and began putting into effect the decisions made in London two days earlier. He issued a secret circular to all County Inspectors of the RIC and all County Commandants of the USC:

“Owing to the number of reports which have been received as to the growth of unauthorised loyalist defence forces, the Government have under consideration the desirability of obtaining the services of the best elements of these organisations.

They have decided that the scheme most likely to meet the situation would be to enrol all who volunteer and are considered suitable into Class ‘C’ and to form them into regular military units [emphasis added].”30

The “unauthorised loyalist defence forces” which Wickham had in mind were the UVF, which had been re-organising since September, and the newly-formed Ulster Imperial Guards. But it was the wording of the circular that created a furore.

A copy fell into the hands of the IRA and on 19 November, it was published in Sinn Féin’s Irish Bulletin and immediately picked up by the London press.31

RIC Divisional Commissioner Charles Wickham issued a controversial circular

Four days later on 23 November, Craig, who was in London to meet the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was confronted over the circular and wrote a hasty note to Bates:

“My attention has been drawn to the terms of Colonel Wickham’s circular of Nov. 9th in regard to the recruiting for Class C Special Constabulary in the event of the Truce being terminated which I approved and for their formation into regular military units. The police having now been transferred to the Government of Northern Ireland recruits may be taken in as police but not into any military force or organisation…circular must be withdrawn.”32

The vehemence with which the matter was drawn to Craig’s attention is illustrated by the fact that his note to Bates was written on 10 Downing St headed notepaper, suggesting that Lloyd George forced Craig to write it there and then.

However, at a meeting the following Saturday, 26 November, attended by Craig, Bates, Spender, Cameron and Wickham, it was decided that “The various Special Constabulary forces are to be brought up to establishment; this entails enrolling at once about 700 ‘A’ Specials and 5000 ‘B’ Specials. Recruiting for ‘C’ Specials to be undertaken at once.”33

Recruiting for the C1 Specials began in late November 1921

The same meeting also planted the first seed for what was to become the Special Powers Act: “The Minister of Home Affairs undertook to consider whether any legislation was required to take the place of the Restoration of Order Act in Northern Ireland.”34

In the event, of course, the Treaty negotiations did not break down but that did not affect the wheels that had already been put in motion: on the very day that the Treaty was signed, UVF Headquarters advised all local units: “I am instructed by the OC [Officer Commanding] Headquarters UVF to inform you that as a new ‘C’ force of Special Constabulary is being organised by the Northern Government that all members should be recommended to join this force.”35

Craig’s climbdown in London had lasted all of three days – he had got back his B Specials and now he was going to have his C1 Specials.

The Norfolk Regiment and loyalists around York St

Within days of the start of 1922, Major General Cameron had pinpointed the source of the main threat to peace in Belfast:

“In my opinion the disturbances are due to unauthorised hooliganism and the IRA officials are not to blame and any action which brought them officially into the field against Crown forces would be most undesirable from every point of view…not only must the Special Constabulary be impartial but tactically the Protestant hooligan should be the first objective.”36

His assessment was undoubtedly coloured by a startling new development just a few days earlier.

Throughout the entire period of the Pogrom, only three British soldiers were killed in Belfast. The first was Private James Jamison of the 1st Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles): on 31 August 1920, he inadvertently walked across a comrade’s line of fire as troops confronted loyalist rioters off Sandy Row. The second was Private Ernest Barnes of the Norfolk Regiment: he was killed on 2 January 1922 – by a loyalist.37

Earlier that afternoon, Lance Corporal Reggie Turner of the same regiment had been leading a patrol in Sailortown in north Belfast. There had been intermittent sniping throughout the afternoon and the patrol was trying to locate the snipers:

“I very nearly got shot by four men who repeatedly fired at me. The deceased fired at me but missed and I returned the fire and hit him…I fired from Garmoyle St and hit the man at the corner of North Ann St. He had a rifle and was about fifteen yards away from me. After firing I saw the man fall to the ground. I saw his comrade pick his rifle up, he aimed at me with the intention of firing and I ran straight across the road into cover behind the corner of Trafalgar St.”38

The man who Corporal Turner shot and killed, Alexander Turtle, was a member of the Imperial Guards – within hours, they had taken revenge.

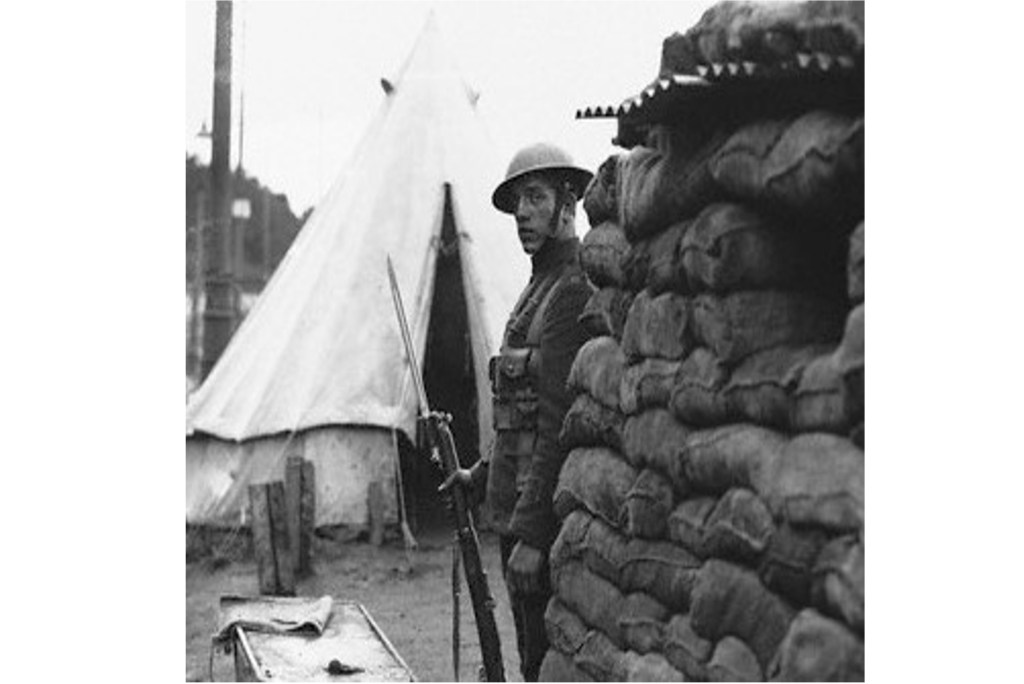

A British military post at the corner of Henry St, one street away from where Private Barnes was killed

Private Barnes was on duty at the junction of North Queen St and Sussex St, a few hundred metres from where Turtle had been killed. According to Burke,

“Later intelligence indicated that Private Barnes was now the target of the Imps’ most feared sniper, Jordy Harper, a veteran of the First World War. Harper’s first shot missed; Barnes’ corporal raised his rifle and replied. Jordy Harper then cooly advanced through the fog towards the soldiers, firing twice before disappearing down nearby Dale Street – one of these rounds fatally wounded Barnes in the chest.”39

The Imperial Guards were particularly active in north Belfast. Two more of their members were killed by British troops in the weeks after Turtle’s death. On 13 February, Ben Lundy was killed in Hardinge St in the New Lodge – according to Burke, “Loyalists blamed the Norfolks for the death;” Lundy was noted as being an Imperial Guard in the newspaper report of his funeral.40

There was little doubt as to who killed Herbert Hassard (also known as Hazzard) in Isabella St off York St on 8 March: an eyewitness told the inquest that he had seen a corporal – from an unspecified unit, but very likely the Norfolk Regiment – fire the fatal shot. The 1st Battalion of the Imperial Guards placed a notice in the Deaths column of the Belfast Telegraph, asking all members to attend the funeral of “our dear comrade.” One of the Norfolks’ Intelligence Officers reported that, “’The Orange mob in York St say they will have 6 Norfolk soldiers for Hassard.’”41

The funeral of Herbert Hassard, an Imperial Guard shot dead by British troops (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 18 March 1922)

But Hassard may also have been involved in attacks against the military. An intelligence document compiled by the Belfast IRA noted that an ex-Special called “Stanley Hassan” had been “Connected with shooting of soldier in Sussex St;” the document does not name the soldier who was shot, so it may have been referring to Private Barnes or to a different incident altogether. There was nobody named Stanley Hassan in the 1911 Census, but the similarity between the two surnames suggests that while the IRA’s intelligence in this case was flawed, Hassard had reaped what he had sown.42

Armed loyalists had imagined that the young, inexperienced post-war recruits to the British Army stationed in Belfast in 1922 would be unable to stand between them and the intended victims of their sectarian attacks; Fred Crawford, commandant of the South Belfast B Specials, described meeting two A Specials – one of them, an ex-serviceman wearing his medals, complained about British troops “interfering” with them:

“You know, Sir, he said, some day we will run across the military and if we do we will eat them up. Most of us have been in the late war and the military are only schoolboys and would be nowhere with us. This is quite true; they are only boy scouts in most of the regiments we have here.”43

Those loyalists were taken aback when the “boy scouts” proved more than capable of fighting them off and perfectly willing to shoot them if needed.

The Norfolk Regiment and Specials in Carrick Hill

On the afternoon of 6 March, a Norfolk Regiment soldier was at the corner of Stanhope St and Wall St in Carrick Hill, when “Suddenly I heard rifle fire from the direction of Denmark St. I at once took cover as the bullets were coming down Wall St…I saw a police Lancia car at the junction of Denmark and Wall Streets and the fire was coming from the car.”44

The Lancia moved off but half an hour later, it was back again. An armoured car of the Worcestershire Regiment came to investigate and the crew commander reported that “as I drove past it the police left the car and men in civilian clothes were behind the rifles in the kneeling position looking through the loopholes.” The men in civilian clothes may have been Specials or they may have been other loyalist combatants being transported in a police armoured car.45

Later the same day, a corporal in the Norfolk Regiment caught a Special shooting at soldiers: “I saw a Special in the act of firing up Lime St [sic – Stanhope St] towards the military post at the junction of Lime St and Wall St. I also saw four empty cartridge cases on the road which the Special picked up. I asked him if he knew that he was firing towards troops, and he told me he was aware of that fact but he was after a sniper up Lime St.”46

The following afternoon, in the same area, soldiers from the regiment shot dead two Protestant men and wounded two others in Hanover St during rioting; in response, enraged loyalists threw a bomb at the Norfolks, wounding four of them.47

There was no respite for the Norfolks: the next day, one of their patrols in Hanover St was fired at by a mixed crowd of Specials and civilians from the Old Lodge Road – a corporal in the patrol reported that the crowd urged the Specials to “’Wipe out the Norfolks.’” A private in the same patrol accosted one of the Specials, who responded, “’If you fellows don’t look out we will knock the Norfolks out of the town altogether.’ One of the Specials then threatened to shoot me at the first chance he got.”48

British soldiers at a barricade

Three hours later, an officer of the Norfolk Regiment visited a military post on Wall St that came under fire, also from the direction of the Old Lodge Road, while he was there:

“Privates Slaughter and Miller saw a Special Constable come out and fire at them. They retired into a house, and in all about 20 shots were fired up this street. The range was about 80 yards and the police had been informed of the disposition of the troops in this area. I shouted down the street to cease fire and two Special police came out with rifles in their hands.”49

These incidents drew an angry response from Lieutenant Colonel Francis Day, the Norfolks’ commanding officer, who reported to 15th Infantry Brigade, “DI [District Inspector] Nixon promised me early in this week that orders would be given to the ‘Specials’ not to fire into this area at all, as I had previously drawn his attention to the fact that the Specials had been firing on the troops.”50

The protest lodged with DI Nixon had no effect. A few weeks later, a Lieutenant Leywood of the Norfolk Regiment was wounded by firing from the direction of Broadbent St on the unionist side of the Old Lodge Road – according to a Provisional Government report, “while on the ground he was heard to say, ‘I know who did this – it was Nixon and his gang.’”51

Protestant civilians continued to voice criticisms of the military. On 7 March, the secretary of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association, A.W. Hungerford, wrote to Craig:

“I have it on very good authority that a patrol of the Norfolks came out of that area [Carrick Hill] and fired on a crowd of people who were waiting at the tram stop at Carlisle Circus. No doubt you are aware of the bitter feeling that exists amongst our people in regard to the Norfolk Regiment and this last act of theirs has greatly incensed our people, and I fear from the remarks which I have heard that a collision between our people and the Norfolks is inevitable.”52

Nationalists were well aware of loyalist hostility towards the Norfolk Regiment. The Irish News even published a satirical article on the subject:

“It concerned his Majesty’s Norfolk Regiment: it was to the effect that all the soldiers in the regiment are Roman Catholics and that all the officers and non-commissioned officers are Jesuits in disguise … The proposition can be demonstrated with the mathematical precision of an Euclidean formula: (1) The Duke of Norfolk is notoriously a Roman Catholic. (2) He is called the Duke of Norfolk because all Norfolk County belongs to him. (3) The R.C. Duke of Norfolk tolerates no one on his property but R.C.s. (4) Soldiers of the Norfolk Regiment come from Norfolk: therefore they are Roman Catholics.”53

In April, there was further shooting between the Norfolk Regiment and Specials, this time near the Marrowbone in north Belfast, which was also within DI Nixon’s area of responsibility. Troops stepped in to prevent loyalists burning more nationalists’ houses the day after most of Antigua St was burnt out – in the ensuing gun battle, a Captain Papworth and Private Grant of the Norfolks were shot and wounded; soldiers then killed Special Constable William Johnston, “who the military claimed had fired on Grant.”54

The day after Antigua St was burnt out, troops from the Norfolk Regiment killed a Special Constable who they believed had shot and wounded one of their fellow-soldiers

A few days later, on 21 April, the scene was almost repeated, but this time without casualties: “Specials fire into Catholic houses in New Lodge Road. Soldiers who came on the scene opened fire on Specials.”55

The antagonism of unionists to the Norfolk Regiment continued to fester. In May, Bates, well-tuned to discontent among his supporters, even proposed to the Northern Ireland cabinet that the regiment be removed from Belfast altogether, although on this occasion he was rebuffed:

“The Minister of Home Affairs stated that there had again been trouble between the Norfolk Regiment and members of the Special Constabulary and considered that the time had arrived when a change was necessary. General Solly-Flood said that he had already discussed the matter with General Cameron who was of opinion that it would be a great mistake to make such a move at the present time. General Solly-Flood said that he was in complete agreement.”56

As late as August 1922, soldiers of the Norfolk Regiment were still being targeted by loyalists. Gelston, by now City Commissioner of the new Royal Ulster Constabulary, noted in a report that on 27 August, “Private of Norfolk Regt fired at & wounded in Boundary St. Prot[estant] area.” Newspaper reports said that Private George Dean had been “walking” at the time, implying that he was off-duty, when he was shot by two men; if he had been wearing his uniform, that may have made him a target.57

The Norfolk Regiment was finally transferred to England on 12 September. It is probably safe to say that they and loyalist Belfast were glad to see the back of each other.58

Part 2 of this article will look at the experiences of soldiers from other regiments of the British Army in west and east Belfast.

References

1 Military Archives, Bureau of Military History, Roger McCorley statement, WS389.

2 Ibid.

3 Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir, Diarmuid Ó Tuama (eds) The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2018), p103

4 Intelligence Officer, 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 22 February 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland outrages, TSCH/3/S11195. Alan Parkinson says that French was killed by a police bullet – see Belfast’s Unholy War (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2004), p226.

5 Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Potter to his mother, 19 March 1922, Princeton University Library Special Collections (PULSC), Herbert Cecil Potter papers. I am hugely grateful to Ed Burke for sharing this resource with me.

6 Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (London, Yale University Press, 2020), p19.

7 Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Potter to his mother, 5 February 1922, PULSC, Herbert Cecil Potter papers.

8 Tim Wilson, ‘“The most terrible assassination that has yet stained the name of Belfast”: the McMahon Murders in Context’, in Irish Historical Studies, Volume 37 Issue 145 (May 2010), p83-106.

9 Minutes of meeting, 23 June 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

10 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), p13-14.

11 Telegram from Divisional Commissioner to all County Inspectors, 10 July 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

12 Edward Burke, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles (Newbridge, Merrion Press, 2024), p47.

13 Patrick Buckland, The Factory of Grievances: Devolved Government in Northern Ireland 1921-39, (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 1979), p188.

14 Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, 16 July 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A; His Majesty’s Stationery Office, Arrangements concerning the cessation of active operations in Ireland, n.d., in PRONI, Instructions to police on observation of truce effective from 11 July 1921, HA/32/1/5.

15 Prime Minister, Northern Ireland to Chief Secretary, Irish Office, 24 August 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

16 Buckland, The Factory of Grievances, p187. The effectiveness of the redeployment strategy adopted by O’Duffy on this occasion may have contributed to the formation of a full-time IRA City Guard in February 1922, which could be used as a reserve to be despatched around the city to bolster local units wherever violence became particularly intense.

17 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 31 August 1921, PRONI, CAB/4/17.

18 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 6pm 31 August 1921, ibid.

19 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 11am 1 September 1921, ibid.

20 Minutes of meetings with deputation, 7 & 12 September 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

21 Colonel Commandant, 15th Infantry Brigade to Prime Minister, 17 September 1921, ibid.

22 David Fee to Minister of Home Affairs, 13 September 1921 & Fred Crawford to Minister of Home Affairs, 17 September 1921, PRONI, Norfolk Regiment: Malvern Street, Belfast, incident, HA/20/A/1/4.

23 Lieutenant Colonel A.H. Yatman to Minister of Home Affairs, 5 October 1921, ibid; General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ulster District to Minister of Home Affairs, 28 October 1921, ibid; GOC, Ulster District to Fred Crawford, 27 October 1921, PRONI, Crawford Papers, D1700/5/4/64.

24 Chief of Police to Divisional Commissioner, 26 September 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence March 1921 – November 1921, CAB/6/27A.

25 Telegram from Chief Secretary, Irish Office, 26 September 1921 & Colonel Commandant, 15th Infantry Brigade to Divisional Commissioner, 28 September 1921, ibid.

26 Draft memorandum, 17 October 1921, ibid.

27 Conference at Cabin Hill, Knock, 20 October 1921, ibid.

28 Precis of interview, War Office, 7 November 1922, ibid.

29 Under-Secretary, Irish Office to Prime Minister, Northern Ireland, 9 November 1921, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence November 1921 – December 1921, CAB/6/27B.

30 Captured RIC memo, 9 November 1921, University College Dublin Archive, Richard Mulcahy Papers, P7/A/29.

31 Daily News (London), 19 November 1921.

32 Prime Minister to Minister of Home Affairs, undated [but 23 November 1921], PRONI, CAB/6/27B Military and police, general correspondence November 1921 – December 1921.

33 Notes of meeting, 26 November 1921, ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Adjutant, UVF [no addressee], 6 December 1921, ibid.

36 GOC, Ulster District to Cabinet Secretary, 5 January 1922, PRONI, Disturbances in Belfast, CAB/6/37.

37 Belfast News-Letter, 3 September 1920. The third military fatality was Lieutenant Edward Bruce of the Seaforth Highlanders, who was killed on 10 March 1922 in Alfred St in the Market; the circumstances of his killing were unclear and disputed – see https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2023/07/22/who-was-responsible-for-the-killings/.

38 Statement of Lance Corporal R. Turner, Courts of Inquiry in Lieu of Inquests, Civilians – Alexander Turtle, Belfast, The National Archives (UK), WO/35/160/27; available at https://search.findmypast.ie/record?id=IRE%2FWO35%2F160%2F00574&parentid=IRE%2FEAS%2FRIS%2F013266

39 Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p63-64.

40 Ibid, p65; Northern Whig, 17 February 1922.

41 Belfast News-Letter, 5 April 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 10 March 1922; Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p68. There was nobody called Herbert Hazzard in the 1911 Census, but there was a 14-year-old boy named Herbert Hassard living in Island Folly near Lisburn, Co. Antrim; newspaper reports on the killing and inquest, and the death notice inserted by the Imperial Guards all spelled his surname “Hazzard.”

42 List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes, July 1922, in List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th 1922, MA, Historical Section Collection, HS/A/0988/15.

43 Fred Crawford diary entry, 13 June 1922, PRONI, Private papers of Colonel F.H. Crawford, D640.

44 Statement by Bandsman H. Hogarth, 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, 8 March 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

45 Statement by Corporal F.G. Cox, 4th Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment, 8 March 1922, ibid.

46 Statement by Lance Corporal G.M. Sutterfield, 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, 8 March 1922, ibid. Lime St and Stanhope St directly faced each other on either side of the Old Lodge Road so the corporal may have thought that Stanhope St was a continuation of Lime St.

47 Northern Whig, 8 March 1922.

48 Corporal W. Knell & Private A. Long to Adjutant, 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, 8 March 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

49 Lieutenant E. Richardson to Commanding Officer, C Company, 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, 8 March 1922, ibid.

50 Officer Commanding, 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment to 15th Infantry Brigade, 9 March 1922, ibid.

51 Report for 9 April 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland outrages Jan-Oct 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

52 Secretary, Ulster Unionist Labour Association to Prime Minister, 7 March 1922, PRONI, Disturbances in Belfast, CAB/6/37.

53 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 18 March 1922.

54 Burke, Ghosts of a Family, p99; Belfast News-Letter, 19 April 1922.

55 Report for 21 April 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach, Northern Ireland outrages Jan-Oct 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

56 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 23 May 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/44.

57 City Commissioner to Inspector General, 25 September 1922, PRONI Military and police, general correspondence September 1922 – December 1922, CAB/6/31.

58 Belfast News-Letter, 13 September 1922.

Leave a comment