Part 1 of this post examined the plans and schemes devised by Major General Arthur Solly-Flood, Military Adviser to the Unionist Government of Northern Ireland, during his first few months in the role. Here, his most contentious proposal is discussed: the abolition of the B Specials.

Estimated reading time: 40 minutes

Financial constraints

On 19 July 1922, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Robert Horne, wrote to the Unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, with what would prove to be bad news for his Military Adviser, Major General Solly-Flood: the maximum amount the Treasury was prepared to provide towards the costs of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) for the financial year April 1922 – March 1923 was £2.85m. This was far short of the estimate of £3.6m compiled by the northern Ministry of Home Affairs two months earlier when Solly-Flood unveiled his initial proposals for re-organising the Specials. But Craig felt he had secured as much as Westminster was prepared to concede and wrote grovellingly to Horne “to express my thanks for the generous manner in which you have acceded to my requests.”1

As a result, by late July, there was pressure to economise on the scale of policing. Solly-Flood told a meeting of Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) County Inspectors that:

“The Colonial Secretary…appeared very much exercised at the lines on which the Ulster Constabulary was organised…there would be a shout to draw in our horns and he knew they would all visualise that we could not go on at the same rate we were doing for ever and that, when the time came, they must effect big economies.”2

However, he was adamant that he “intended to preach the gospel that the time was not ripe or anything like ripe to carry out drastic reductions in the Special Constabulary.” Instead, he planned to reduce the Specials’ clothing allowance and instead issue them with government clothing and pay them a patrol allowance.3

But such piecemeal measures were never going to have the required financial impact: a cabinet meeting on 27 July decided that at most, Solly-Flood’s proposals would only save £0.5m, only half of what was required to bring spending within the limits that the UK Treasury would cover.4

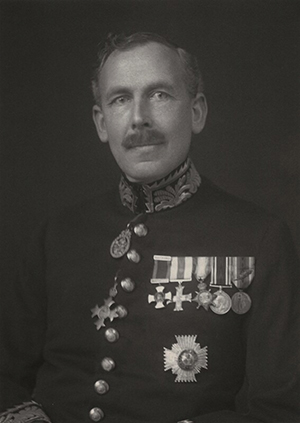

Military Adviser Major General Arthur Solly-Flood resisted making cuts to expenditure on the Specials

Craig and his Minister of Education, Lord Londonderry, shared a dim view of Solly-Flood’s fiscal delusions. Craig wrote, “It is somewhat ungracious of Solly-Flood to take the attitude he does, and confirms my opinion that the one thing he does not understand is finance in any shape or form.” The minister concurred: “What he does not appreciate is the stringency of the money question, and thinks that you are able to draw from the British Government the sums we require, not realising that the British Government has no money to give away.”5

At its meeting on 9 August, the government decided to take action far more dramatic than the token gestures offered by Solly-Flood: from October, the pay of full-time A Specials would be cut by almost a third, from 10/- to 7/- a day and the B Specials’ annual payment would be halved from £10 to £5. Most significantly, the number of full-time men, between regular RUC and A Specials combined, would be reduced to 6,000 by the end of 1922; this represented a massive reduction, particularly in the number of A Specials, of whom there had been 8,226 in July.6

At the same meeting, the cabinet also began to ease Solly-Flood out of his role, deciding that “…the Military Adviser and the Inspector General RUC were requested carefully to review the whole situation from time to time with a view to establishing whatever additional Special Constabulary may be considered necessary on the basis required by the Inspector General RUC.”7

Solly-Flood felt insulted, pointing out that “The corollary to such a decision is that the policy to be adopted rests with the Inspector General RUC.” He was absolutely right – Charles Wickham, the Inspector General, was now in charge of the Specials again.8

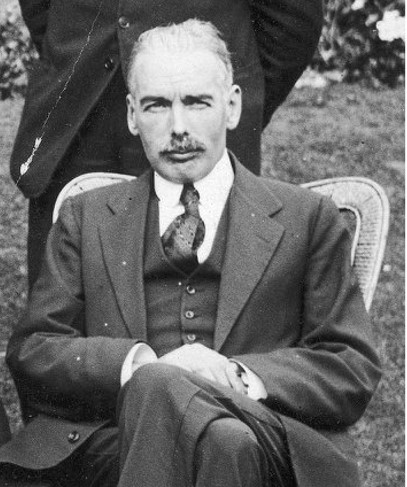

Responsibility for the Special Constabulary was returned to RUC Inspector General Charles Wickham

In high dudgeon, Solly-Flood washed his hands of what he felt was turning into a cut-price Special Constabulary and tendered a partial resignation:

“In view of the fact that it is clearly brought out by the decisions that the paramount importance in the opinion of the Cabinet at the present time are, firstly economy and secondly that the IG RUC would eventually assume command, I have expedited the latter event and delegated to him the control of the whole of the Constabulary so that the Special Constabulary may be re-organised on the basis which in his opinion is most desirable…

I now beg to request that I may definitely be relieved of the control of the Constabulary and of the responsibility for the maintenance of law and order in Northern Ireland and be permitted to revert to the duties allocated to me…namely, those of Military Adviser to the northern government.”9

Craig subsequently attempted to soften the blow, writing a personal letter to Solly-Flood while they were both on holidays, “Perhaps as the IG has to carry on it might be as well to let him feel the full weight early as late, and you, as our Military Adviser, can give him the advantage of your ripe experience and technical knowledge.”10

However, Solly-Flood responded to this olive branch by lashing out at those around him: “The rift within the [illegible] is firstly, Dawson Bates’s inability to keep in view the ultimate situation, and secondly Wickham’s complacency. I have found the latter thro’out far too pleased with himself, his ideas and his methods.” But in an exceptionally rare moment of self-reflection, he then went on: “However to be continually crying wolf becomes tiresome to oneself and to one’s hearers.”11

Eventually, at a cabinet meeting in mid-September, Craig informed his colleagues that a compromise had been reached:

“The Prime Minister stated that he had received from the Military Adviser his resignation from the command of the Constabulary forces, owing to the fact that his recommendations for the future constitution of these forces could not be approved by the Cabinet owing to the question of funds…The Military Adviser would draw up a scheme for the constitution of the Special Constabulary for the next financial year, which would be submitted to the cabinet.”12

An enemy within: an IRA spy

Solly-Flood’s already creaking credibility was severely damaged when it emerged in late August that one of his staff had been an IRA spy.

Pat Stapleton had been an officer in the Royal Irish Rifles during the Great War; after the war, he secured work as a clerk in Victoria Barracks, the British Army’s headquarters in Belfast. He began to pass information to the IRA, taking files from the barracks, handing them over to be copied overnight by David McGuinness, Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, and replacing the files the next day.13

In the summer of 1922, Stapleton was transferred:

“He (our contact) took up duty as Confidential Clerk to Major General Solly-Flood at Waring Street Headquarters. The same procedure was carried out here as at Victoria Barracks and when a suitable occasion presented itself the files were abstracted, brought to us to be copied and returned the following morning.”14

However, the pressure of living this double-life was taking its toll on Stapleton, so on 19 August, he stole one last batch of files, gave them to the IRA and took the next train to Dublin.

Samuel Watt, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, investigated and was critical of the fact that the news of Stapleton going missing was initially kept from the RUC, allowing the trail to grow cold: “I cannot help pointing out that it is most unfortunate that the inquiries following his disappearance, in the first instance, were made by the CID [Criminal Investigation Department] alone. The fact was not reported to the permanent police for five days.” However, Solly-Flood’s staff assured Watt that “the files missing were not of a highly secret nature…not much public damage had been done.”15

As late as October, Solly-Flood was still attempting to put a brave face on the matter, insisting, “Definite information is however to hand that up to the 6th October none of the documents he is alleged to have taken have reached Beggars Bush GHQ.”16

But Solly-Flood was either bluffing or lying. In fact, Séamus Woods, O/C of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, brought the files to Dublin personally the morning after Stapleton stole them.17

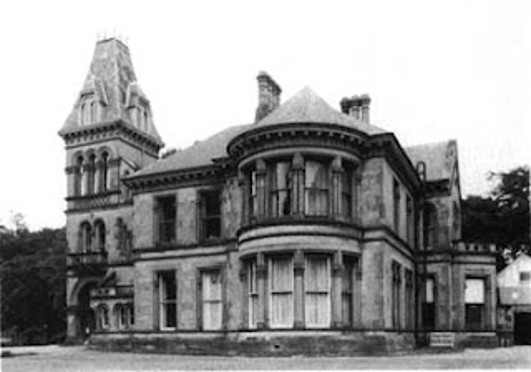

RUC Headquarters, Waring St, where Solly-Flood’s office was located and from which an IRA spy stole files

They are now part of the Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents collection in the Military Archives. They further illustrate the efforts of Solly-Flood’s office to downplay and cover up the extent of the affair: they told the Ministry of Home Affairs that fourteen files were missing, but Woods brought sixteen files to Dublin. It would appear that Solly-Flood’s office conveniently forgot to tell anyone about two others.18

The first was titled “Establishments (Provisional) C1 Division” – this set out Solly-Flood’s updated and detailed plans for the organisation, manpower and equipment of the C1 Specials. Of all the stolen files, this was probably the most valuable to the IRA, as it told them exactly what to expect from one of their key opponents.19

The other was simply called “Navy.” At the end of March, the anti-Treaty IRA had seized a large quantity of arms and ammunition from a Royal Navy vessel, the RFA Upnor, in Cork Harbour. Accordingly, Solly-Flood started developing plans for the maritime defence of Northern Ireland, only for the Royal Navy to haughtily insist that this was their responsibility and that they had the matter in hand. Solly-Flood was reduced to suggesting that the Government of Northern Ireland buy a second-hand steam-powered boat from a man named Samuel Gray so that Specials could patrol Lough Neagh.20

The northern IRA had not previously shown any capability for amphibious warfare and while the Free State Army did mount seaborne landings in Cork and Kerry in August, Lough Neagh, being completely landlocked, did not offer the same strategic possibilities. In the event, Gray was left to find a customer elsewhere and Solly-Flood girded his loins to deal with the next attack.

Achilles heel: the Criminal Investigation Department

On his appointment in April, Solly-Flood had been given cabinet approval for his plan to establish a “Secret Service” – this took shape as the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). Paul McMahon, author of British Spies & Irish Rebels, quotes a British military intelligence report which reflects a glowing opinion of the CID, possibly because of who was in charge of it:

“This organisation was composed almost entirely of men with military experience…The results of their advent were almost instantaneous. Liaison which before had been difficult was now a matter of routine; co-operation was made almost as perfect as possible; and in a very few weeks the power of the IRA was broken…”21

The CID reported directly to Solly-Flood. It was initially led by Lieutenant Colonel Maldwyn Haldane, who had previously been on the staff of Colonel Ormonde de l’Epée Winter, the Director of Intelligence for the Royal Irish Constabulary throughout Ireland, based in Dublin Castle. Haldane’s supporters no doubt highlighted his experience of intelligence operations in a counter-insurgency; his critics may well have pointed out that those had not been intelligence operations in a successful counter-insurgency.

Lieutenant Colonel Maldwyn Haldane, the first head of the CID (© National Library of Ireland)

As the CID had been his creation, Solly-Flood was prone to exaggerating its impact: “The number of seditious and dangerous documents revealing the plans of Sinn Fein, which have been captured, have been almost unlimited. The captures…have been largely due to the activities of the Criminal Investigation Department.” Another document referenced the capture of Desmond Crean, who was a mid-ranking IRA Intelligence Officer – Solly-Flood promoted him to “O/C Belfast Brigade.”22

He wanted the CID to take the lead in suppressing the IRA, with the military and police merely playing supporting roles in terms of intelligence and raiding:

“It was decided there would only be one collecting and collating authority for information via the CID. That the military and RUC should inform the CID with regard to any information they have obtained. That the CID should be the sole authority for organising raids, that the police with or without the help of the military should carry them out in their entirety.”23

He even proposed putting the CID in charge of the internees on the Argenta, but when the Cabinet Secretary, Wilfrid Spender, heard of this notion, he witheringly remarked to Craig: “I think that in view of the fact that one of his own staff proved to be a spy, it is a little rash for him to suggest that the CID is competent to take over the staffing of the ship.”24

The admiration of military intelligence and Solly-Flood for the CID was not universally shared. The CID had a bad name even beyond those directly concerned with security matters – John M. Andrews, Minister of Labour, told Craig: “There is also very general criticism as to…the class of men which he [Solly-Flood] is recruiting, arming and giving passes to for Secret Service work.”25

Danesfort House

Danesfort House, where the CID was based, already had a seedy reputation as a result of orgies that Solly-Flood’s staff were rumoured to host there. That reputation was only compounded by the CID’s recruitment of common criminals as informers. Just after midnight on 17 August, Frederick Edwards, accompanied by “a bookmaker’s clerk and two barmaids,” demanded rooms in a hotel in Royal Avenue; when the hall porter refused to let them in, Edwards pulled a gun on him. Just before 2am, a police patrol arrested them outside another hotel in York St where they were trying to get admission. At the police barracks, Edwards produced “identification papers showing that he was attached to CID Danesfort.” He was subsequently released from custody without charge and “dealt with from a disciplinary point of view.”26

He was not the only criminal arrested by the RUC to use a CID identity pass as a literal get-out-of-jail card: George Shaw, James McGrath and Edward Dowling were others who did so over the course of July and August.27

The most egregious such case was probably that of Robert Craig, chairman of the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), a loyalist paramilitary group active in east Belfast which was suspected by the police to have carried out the killings of a number of Catholics and even to have killed a Special Constable who intervened to stop them killing two men. Robert Craig was taken on by Haldane as early as 17 June, as he had a “strong recommendation” from the Ministry of Home Affairs. Even his CID handler complained: “Neither he or his friend Smith ever gave us any good information which we were led to believe they could furnish…We have had nothing but trouble with these two men since they were engaged.” With the protection afforded by his relationship with the CID, Robert Craig was allowed to continue his UPA activities, only eventually being interned the following November.28

The CID’s failings were used by both the civil service and senior political figures as an avenue of attack to undermine Solly-Flood’s position. The Ministry of Finance complained: “Experience has shown that the value of information or other results obtained from the expenditure of Secret Service bears no relation to the amount of money expended…The employment of regular agents brings a flow of useless information furnished to justify the continuance of payment.”29

Spender wrote to Craig, highlighting the “present deplorable friction existing between them [the CID] and the RUC.” But his main concern was not so much the undesirables working for the CID, but its lack of results: “All I know is that inside Ulster we are getting far more reliable and detailed information through the RUC and Special Constabulary than the CID are collecting through other sources.”30

The Minister of Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates agreed, telling Craig,

“I have not the least confidence in it. The blunders of which they have been guilty, and the employment of men of the criminal class in such a way as to cloak the latter with authority, have brought the CID in a most unfortunate way before the public…I cannot agree that they have contributed to the recent diminution of crime.”31

The three threats to Solly-Flood’s position were all of his own making. He stubbornly refused to accept that his plans for the Specials had to be created within financial constraints that were imposed from London. Although he did not personally offer Stapleton a job, the revelation that he had employed an agent of the northern government’s deadliest enemy became an enduring embarrassment. The CID was entirely his conception so he stood or fell with it, but for all his lauding of its efforts and attempts to give it a more prominent role, the grandees of unionism felt it was employing criminal reprobates for little or no reward in terms of intelligence.

By the early autumn of 1922, Solly-Flood was like a wounded wildebeest and the hyenas in the Unionist government were circling.

Keeping the crisis alive

Despite relinquishing his formal responsibility for maintaining law and order, Solly-Flood still had a vested interest in Northern Ireland remaining under threat: if the crisis which the Unionist government had faced in the first half of 1922 diminished, then the need for tens of thousands of C1 Specials might not be so apparent and the government’s need for a Military Adviser might also be questioned.

In mid-August, he began trying to demonstrate that the danger posed by the IRA was still real: he wrote to the Ministry of Home Affairs, giving anecdotal evidence from letters intercepted passing to and from northern IRA men in the south, including one sent to a Volunteer Cewsealey of “6th Northern Division” (sic) in the Curragh, “I hear some people say the Belfast boys are getting sent home again.” Patrick Kane, an IRA member from Ballymacarrett who had returned to Belfast, was interrogated and said: “I am a member of the Free State Army…I belong to the 3rd Northern Division…Yes the 3rd Northern Division are controlled by GHQ Dublin…We are under Michael Collins.”32

Solly-Flood also claimed that a John Duffy, formerly Captain of D Company, 1st Battalion, Belfast Brigade, had recently returned from the Curragh, as he had been “promoted to Commandant and is chosen as the leader of the Northern Division to operate in Ulster.” Only in Solly-Flood’s world would be a company captain suddenly be elevated to command a division.33

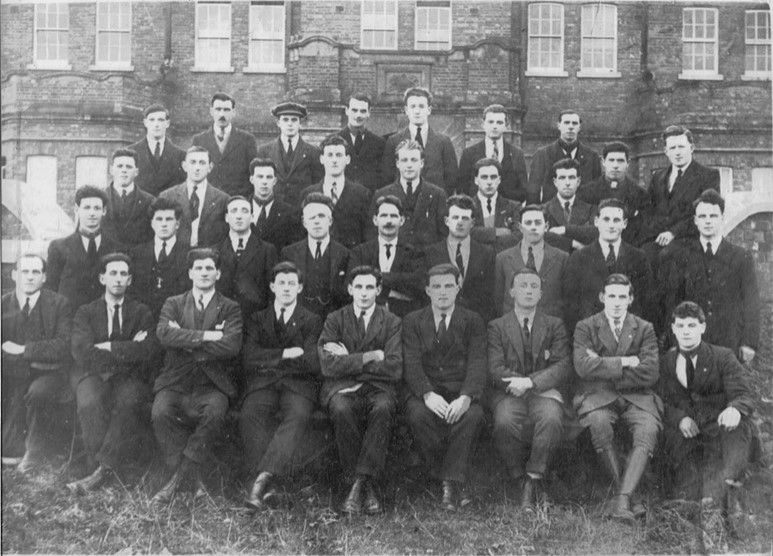

Members of the IRA’s Antrim Brigade in training at the Curragh, Co. Kildare

He went on to issue a dire warning:

“There would appear to be very little doubt that a movement is afoot to pester the northern government of Ireland and so get them to order the release of many of the internees on the ‘Argenta’, as many of them are very valuable officers and members of the IR [Irish Republican] movement.

When they have gained this point the officering of the NEW FORCE will be quickly completed, and operations will begin in earnest. The men are being trained in the various camps just over the border and returning to their homes to await the ‘call to arms.’”34

The following month, Solly-Flood wrote directly to Craig’s secretary, stating that the same John Duffy mentioned above was now back in Belfast, but this time having returned from Omeath in county Louth rather than from the Curragh, and was now “promoted to Comdt Belfast Brigade.” An anonymous civil servant noted in the margin, “This is the CID counterattack on RUC!”35

He also claimed that the IRA’s arson campaign of the previous May-June was about to be resumed: “A very reliable agent in close touch with Sinn Fein circles in Belfast and district reports:- ‘Dated 11th Sept. 1922 Burning of premises may be expected to commence again very shortly.’”36

The British Army decided to withdraw troops from the streets of Belfast as the city was peaceful

Solly-Flood’s efforts to fan the flames of crisis were not helped by a proposal made by Major General Archibald Cameron, General Officer Commanding of the British Army’s Ulster District on 16 August, the same day that Solly-Flood began his doom-mongering. Cameron actually felt that Belfast was now so peaceful that his troops could be withdrawn to barracks:

“In view of the fact that the city of Belfast has been quiet for the past six weeks the commander of the 15th Infantry Brigade proposes from August 21st to take all troops employed on permanent patrols and posts off the streets. He will however leave in each troublesome area a piquet…It appears to me that the time has now arrived when the troops should cease to do police duty in Belfast, and should only be called out in cases of disorder with which the police are unable to deal.”37

Wickham requested that military patrols be continued in five particular streets but apart from that, he and his officers had no issues with the general’s proposal.38

But almost three weeks later, Solly-Flood shoved his oar in, although this intervention was to backfire disastrously on him.

He complained to Spender that the government should have sought his advice before responding to the general. Spender, quite reasonably, pointed out that Solly-Flood had been away on holidays at the time. But there was a sting in the tail: Spender also said that from now on, any communications to Solly-Flood would only come from the Ministry of Home Affairs, rather than the Military Adviser being automatically copied on memos sent by Spender. In effect, Solly-Flood was being shut off from having direct access to Craig or the cabinet. Spender concluded acidly, “This suggestion has the approval of the Minister of Home Affairs.”39

However, Solly-Flood did not let the matter rest.

He despatched two of his staff to inspect some of the military posts in question and then wrote to General Cameron, patronisingly telling him that they were satisfied with the dispositions they found and that he agreed with the general’s decision to withdraw his men to barracks. If Cameron replied, his response is not recorded; he may have been tempted to file Solly-Flood’s memo in the bin.40

Craig had advised Solly-Flood to let Wickham “feel the full weight” – he responded by piling the weight on with enthusiasm. He began trying to undermine Wickham and the RUC City Commissioner for Belfast, J.F. Gelston, writing to Craig’s secretary on an almost-daily basis, criticising the actions of the RUC. Typical of this carping litany was:

“It appears the police no longer carry out the plan recently so successful of cordoning and turning an area inside out, early curfewing, etc where outrages occur…I advise the government to instruct the police authorities to take immediate and drastic steps as above – half measures are futile and are treated with contempt.”41

The following day, he complained that “no less than fifteen useless searches were made, these unproductive half-measures have a deplorable public effect.” None of this was likely to endear him to Wickham or Gelston.42

Most disastrously for himself, Solly-Flood wrote to Spender, complaining that “The Prime Minister’s most recent ruling as regards the channel of communication was for me to correspond direct with him or the Secretary to the Cabinet, sending a copy to the Ministry of Home Affairs.”43

Solly-Flood attempted to undermine RUC City Commissioner J.F. Gelston

The only effect of this was to draw forth a new ruling from Craig – at the end of the month, Spender replied to Solly-Flood, no doubt gleefully:

“1. On the question of the re-organisation scheme of the Constabulary Forces, the Prime Minister will be glad if the Military Adviser will correspond with this office.

2. In regard to all other matters, the Military Adviser should correspond with the Ministry of Home Affairs, but in matters of urgency and importance the Prime Minister would be glad if copies would be directed to this office.”44

Abolishing the B Specials

The government had tasked Solly-Flood with devising a plan for the Specials for the following financial year. In advance of him unveiling his proposals, Craig attempted to give him some friendly advice:

“May I again appeal to you on three points:

(1) Do let us make the best of that personnel which lies to our hand.

(2) Balance most cautiously the interests, financial and otherwise, of the country districts as opposed to the city of Belfast and other large urban centres.

(3) Wickham and the RUC should be helped in every way in our power, bearing in mind the great differences between regular police and those forces of a military character temporarily required in an emergency.”45

The following day, Solly-Flood wrote to Craig, enclosing his plans for a new Territorial Special Constabulary. He not only blithely disregarded Craig’s advice but also attempted to overturn the government’s decision at the start of August.

Instead of the existing categories of A, B, C and C1 Specials, there would be three divisions of Territorial Specials, each consisting of 10,000 men – a Northern, covering Tyrone, Derry and Antrim; a Southern, covering Fermanagh, Armagh and Down; and one in Belfast. The rural divisions would be sub-divided into three groups, each corresponding to the county boundaries. The CID would continue in existence, and there would also be a central training school at Lurgan and ancillary services.46

The members of the new force would be required to attend drill or perform an unpaid night patrol once a week; in addition, they would have to attend an annual training camp. Any patrols beyond the minimum one per week would be paid for and allowances of 3/- (shillings) a day would be paid in the event of full mobilisation and attendance at the training camps.47

However, any current A Specials would lose their already-reduced pay of 7/- a day, while B Specials would lose their £10 annual allowance for meals. Most crucially, when mobilised in an emergency, they could be posted anywhere in the north – this was certain to be a bone of contention, particularly among the B Specials, for whom one of the attractions of enrolment was that they served only in their own local areas. Interestingly, in the event of mobilisation, there would be “No allowance for rations” – perhaps the Territorial Specials were to march on empty stomachs.48

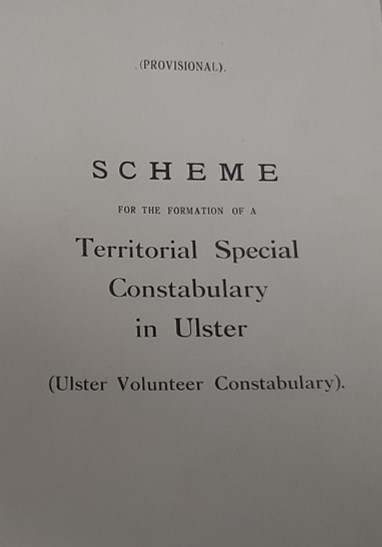

Solly-Flood proposed the abolition of the B Specials

Solly-Flood sought not only to award himself a grandiose new title, but also to undo Wickham’s assumption of responsibility for the command of all police, both regular and Specials: “The whole together with the CID to be commanded by the Military Adviser with the title of Director General of Public Security, who should also command the regular RUC through their Inspector General.”49

In effect, this amounted to withdrawing his resignation from control of the constabulary which Craig had communicated to the cabinet less than ten days earlier.

Foreseeing opposition from existing classes of Specials, Solly-Flood argued that “the inception of the Territorial Special Constabulary is not a change but an evolution; that there is no intention of scrapping the present categories but rather that of merging them into one cohesive force.” But no attempts at deft word-play on his part could disguise the fact that the A, B, C and C1 Specials would cease to exist as such.50

He estimated that in peacetime, the cost of the force, including himself, his staff and the CID, would be £570,000 a year; this included provision for 157 officers and 1,190 other ranks, all of whom would be full-time.51

So convinced was Solly-Flood of the merits of his plan that he got it printed up as a pamphlet to be circulated to all relevant government departments once the cabinet had given its approval. This printed version concluded with an appeal to the recent history of Ulster unionism: “…there must be maintained in Northern Ireland an efficient Royal Ulster Constabulary backed by a well-organised Territorial Special Constabulary, perhaps called the Ulster Volunteer Constabulary [emphasis added] and an efficient CID, the whole to be at all times under the hand of one Commander.” This blatant attempt to grab onto the coat-tails of the UVF was curiously absent from the typewritten version of his plan which Solly-Flood sent to Craig.52

Front cover of the pamphlet containing Solly-Flood’s proposal © PRONI HA/32/1/335; reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI

The plan drew a predictably hostile response from within government circles – the most devastating onslaughts came from Spender and Bates.

Spender wrote to Craig on 21 September, the day after Solly-Flood had sent the plan; although he claimed not to have seen it, he was clearly well-informed as to its contents. He alleged that Solly-Flood’s financial estimates had been falsified: “I understand that the finances of his scheme, as prepared by his own experts, total something over one million pounds, but that he has cut this figure down very considerably in presenting the scheme to you.”53

He highlighted the danger of blurring the separation of powers between different government bodies: “To bring the police directly under the military command except during a period of actual warfare is against the experience of all other nations…Solly-Flood is not particular in maintaining forms of law and order, but merely thinks of his object irrespective of civil laws or other inconveniences.”54

He foresaw difficulties with recruitment and the likelihood of disenchantment among existing Specials: “…even such an optimist and enthusiastic soldier as McClintock [USC County Commandant for Tyrone] cannot hold out hopes for Tyrone providing more than one-half of the number suggested…everyone is agreed it will cause grave unrest among the forces which we now possess.”55

He vehemently criticised the bloated superstructure that would sit at the top of the new force: “I cannot for a moment believe that the War Office could approve of the enormous staffs which will be required for GHQ divisions, brigades, etc.”56

Cabinet Secretary Wilfrid Spender opposed Solly-Flood’s plan

He also played an intriguing Ulster-versus-British card when criticising Solly-Flood and his staff – both current and future – on the grounds that they were outsiders:

“…in Parliament there will be great criticism over the fact that so many British officers are receiving such high rates of pay when you have cut down the pay of the Constabulary…there seems to be no doubt that the number of officers required for this organisation cannot be found locally. This means a large importation from outside, which will be greatly resented in Ulster.”57

Spender was especially hostile to the idea of the B Specials being abolished: “I have discussed with various people how best to meet all these difficulties and the general consensus of opinion is that the Police ‘A’ Special Constabulary and ‘B’ Special Constabulary should remain under the Home Office and be entirely independent of a Military Adviser.”58

As Craig was then in England, it is very possible that Spender’s letter crossed with one which he sent to Spender on 22 September, enclosing a copy of the plan. Craig was not prepared to countenance anything which would involve losing the B Specials:

“…on the one hand I am most desirous of bringing Solly-Flood and his staff along with us, and on the other, feel that the ‘B’s’, upon whom we must rely, may be disorganised to such an extent that they will not respond in case of a further crisis…It may be, however, quite possible to modify the scheme and safeguard the ‘B’s.’”59

In a signal that Solly-Flood was about to be thrown to the wolves, Craig duplicitously told Spender, “In the meantime, please do not let it be known that you have the scheme under consideration.”60

Bates weighed in a week later, having first sought Wickham’s own view of what constituted the best security plan for Northern Ireland. Bates set out to torpedo Solly-Flood’s plan before the government even met to consider it – he circulated Wickham’s memo to his cabinet colleagues, with his own damning evaluation of the Military Adviser’s proposal acting as a cover-note: “I suggest that the Cabinet should be slow to adopt these far-reaching proposals of the Military Adviser.”61

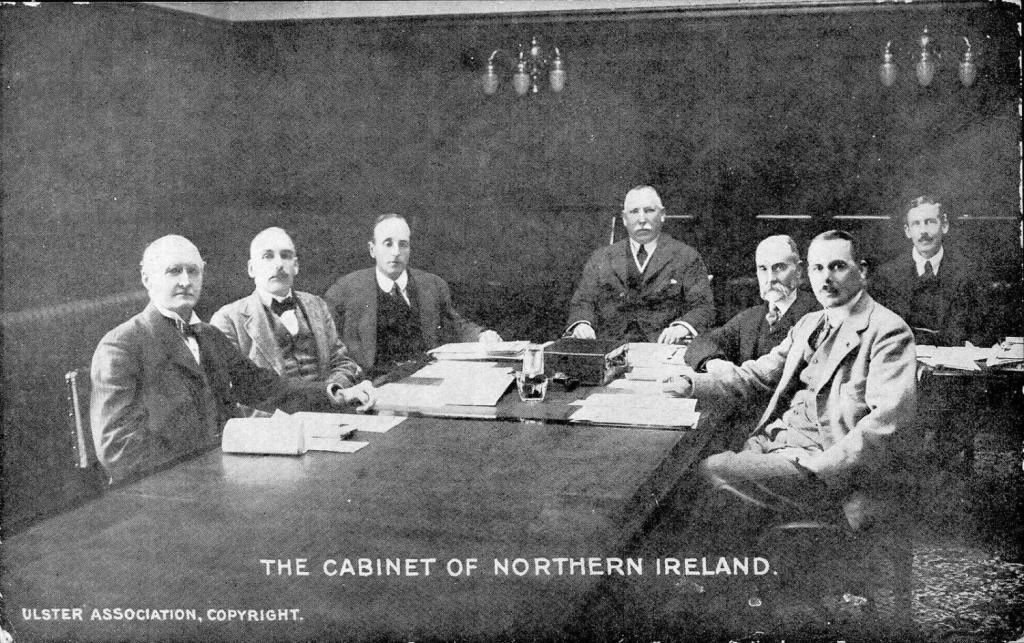

Minister of Home Affairs Richard Dawson Bates also opposed the plan

He plunged four daggers into Solly-Flood’s plan – the first of these provides a telling insight into Bates’ view of the C1 Specials’ primary purpose:

“1. The proposals could only be made effective by legislation, involving the principle of compulsory service…I feel certain that few of the ‘B’ men would accept service under the conditions proposed and the result would be that the province would lose the services of men who have proved of the greatest possible help in preserving the peace during the last two years. Many of the ‘C1’ men, while suitable to act in a punitive force, would be altogether unsuitable as policemen…

2. The scheme limits unduly the power of Parliament, as it in effect sets up dictatorship by a military staff…

3. …the public here would resent the continuance of the present high salaries which are paid to the headquarters staff…

4. I am opposed to the continuance of the CID as at present established…”62

Spender had forecasted that there would be disenchantment among existing Specials about Solly-Flood’s plan. Before that prospect became real, existing feelings of discontent about reductions in the Specials’ numbers and pay threatened to escalate to outright mutiny – a man appeared in court in Belfast on non-political charges but:

“The police…discovered in the possession of the prisoner a passbook containing the following entry pertaining to the Special Constabulary:- ‘Call mass meeting for 2pm Tuesday. Open air. City Hall. Come armed if possible. What action will be taken if any are dismissed? Proposed: Suspend all duty. Power Station, Gas Works, City Hall and Parliament House to be taken over and held until men are reinstated. Carried.’”63

There was an upsurge in sectarian violence in Belfast during late August and September, which Gelston attributed to the Specials – he viewed this as:

“…simply an endeavour to keep the trouble active in the city. At the disbandment of the mobilised B and C1 Specials, there was considerable apprehension that trouble would break out, and it was expressed by some persons as their opinion that it would be organised so as to keep them mobilised. In one case of bomb-throwing, the police have received most reliable information from a Protestant source that the bomb was thrown by B Specials.”64

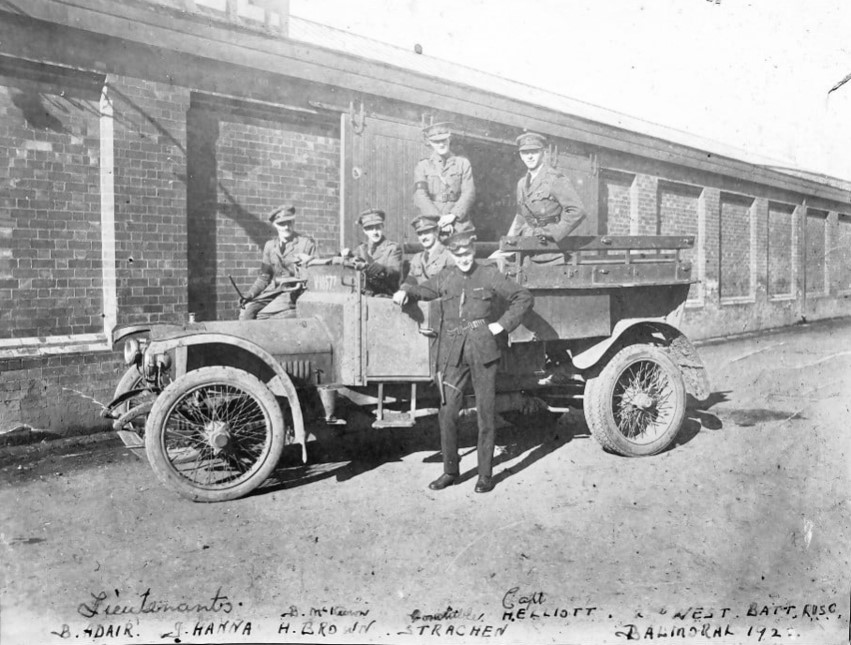

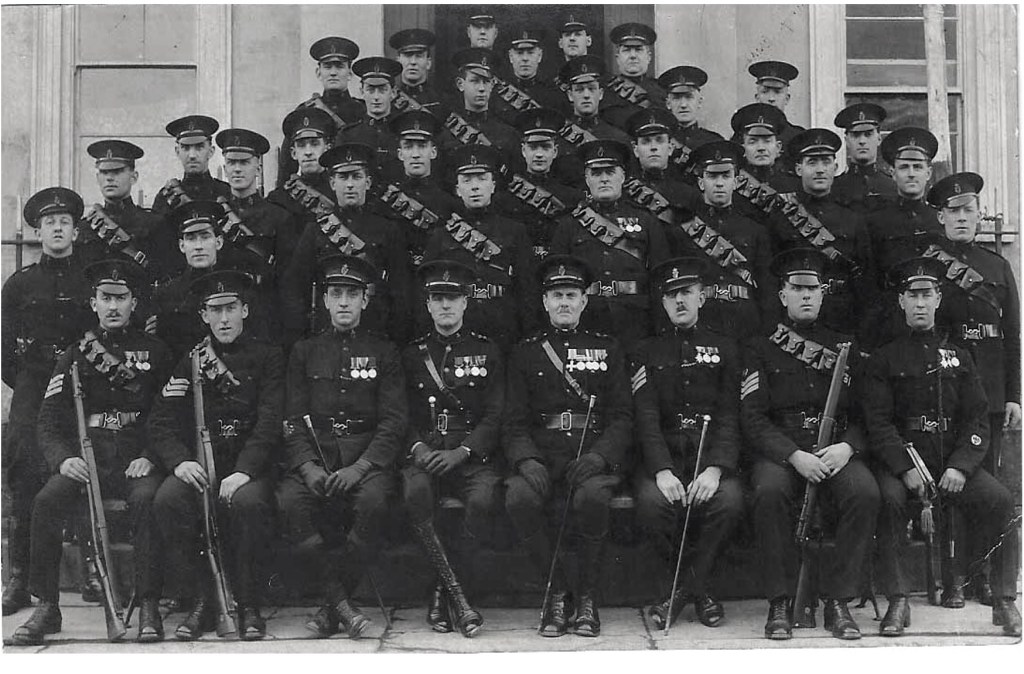

Officers of 2nd West Belfast Battalion, C1 Specials; the RUC believed that Specials were behind an escalation of sectarian violence in August-September (www.irishconstabulary.com)

Less violent ways of communicating their concerns through official channels did bear fruit for the Specials. Following representations from their County Commandants, the decision to halve the B Specials’ annual allowance to £5 was rescinded.65

The cabinet reviewed Solly-Flood’s latest proposal on 4 October. Unsurprisingly, they were unwilling to countenance abolition of the B Specials: “owing to political considerations, it is inadvisable to put it into operation.”66

But they moved beyond mere rejection of his plan to make significant changes to his responsibilities: “He is to advise the Prime Minister and the Cabinet – and them only – regarding the general defence of the Six Counties against outside aggression…In the event of an attack upon the Border or a ‘rising’ within the Six Counties, the Military Adviser will be asked to assume supreme command of such forces under the jurisdiction of the Government of Northern Ireland [i.e. the RUC and Specials, but not British troops] as are required for military operations.”67

Solly-Flood’s beloved CID was to taken away from him: “The CID will in future be, for all purposes, under the authority of the Minister of Home Affairs.”68

And while Bates would get the CID, Wickham was to get the C1 Specials:

“The suggestion that as the ‘C1’ was mainly a military force and would be at the disposal of the Military Adviser in time of emergency, it might be better for the Military Adviser to have control in peace, was very carefully considered. On the whole it was thought better that the whole of the Constabulary forces should be under one command – that of the Inspector General.”69

Terrified of losing the political support of the Specials, the government had completely retreated from the idea of making any more changes to the force than those which had already been announced. Meanwhile, Solly-Flood was back to where he had begun in the spring: a general without an army.

Naturally, he was furious and responded caustically the next day:

“(a) Early in 1922, the Northern Government was frightened of Sinn Fein: this entailed expenditure.

(b) In August 1922, Sinn Fein having been superficially suppressed, the Northern Government became frightened of the Imperial Government and expenditure: this entailed drastic measures for immediate economy.

(c) In September 1922 the Northern Government became frightened of their own people: this entailed, (1) the scrapping of plans for reconstruction which would have given a settled policy in relation to Constabulary matters…(2) In part, the scrapping of plans for effecting immediate economy. (3) The maintenance of the Special Constabulary on lines which in the Military Adviser’s opinion are entirely unsound.”70

Solly-Flood accused Craig’s government of being frightened of “Sinn Fein…the Imperial Government…their own people”

Theatrically, he continued: “…since the Northern Government’s present potential enemy is their own people it cannot be logically argued that the services of a Military Advisor are necessary, and his position therefore becomes both invidious and redundant.” He then claimed he would have to wrestle with his conscience over continuing to draw pay as a Military Adviser if his advice was going to be as ignored in the future as it had been in the past; if his conscience won, “he will be reluctantly compelled to recognise the fact that the parting of the ways has been reached.”71

Disaffection among C1 Specials’ officers?

In November, the general discontent spread to the C1 Specials, although unlike the As and Bs, theirs was initially voiced by the officers rather than the rank and file.

The commanding officers of each of the eight C1 battalions in Belfast signed a joint letter to Lieutenant Colonel William Goodwin, the overall Commandant of the C1 Specials: “There is a general impression in all ranks that the force is being starved.” Attendance at drill sessions was only 8% – 10%, funds were so short that “application has to be made to HQ for authority to purchase even a notebook,” weapons for training were so few that “amongst four battalions there are so far two miniature rifles to carry on with;” as well as all this, “Absolutely no training is being done owing to the absence of any materials or facilities for training.”72

Wickham met the battalion commandants on 20 November and explained the financial constraints the government faced in relation to the whole of the USC. A few days later, the eight officers met again – this meeting saw a startling development which led to another crisis for Solly-Flood.

Colonel V.A. Haddick, himself one-time Commandant of the C1 Specials’ 1st North Belfast Battalion but now attached to the CID, also attended the meeting: he produced a document, which he urged the eight officers to sign,

“…urging that representations be made to the Imperial Government with a view to the C1 division being formed into Militia; the activities of the force to be controlled by the Government of Northern Ireland in time of peace, and the force to be available for service in any part of the world in case of war.”73

Taken aback, the officers refused to sign the document and demanded to know who was behind it. Haddick told them he was not allowed to divulge names but that “it came from the Intelligence Staff at the instigation of the War Office.” He further told them “’I am instructed to say if you don’t agree to this document and sign it you are down and out.” After the meeting Haddick told one of the officers that if they doubted the document’s authenticity, they could discuss it with Colonel Waters-Taylor, who was now in charge of the CID.74

Bates told Craig that Solly-Flood had been negotiating with the War Office for the C1s to be taken over by the British government as a unit of the Territorial Army. When challenged by Spender, acting on behalf of Craig, Solly-Flood denied any knowledge of the document or any role in its being drafted.75

Before replying to Spender, Solly-Flood sent a brief handwritten note to Craig that ranks as one of his most bizarre communications since his original appointment. By now, he was reduced to the anguished quoting of poetry – the entire text of the note read:

“Do you know Rudyard Kipling’s ‘If,’ it goes something like this:-

‘If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating, etc’

It bears a curious analogy to my existence in Northern Ireland recently.”76

A week later, Solly-Flood resigned as Military Adviser, on the grounds that:

“(a) My advice has, in no single instance since comparative quiet supervened, been accepted…

(b) My advice during the same period has not been sought, and when…I have tendered it, it has, so far as I can be aware, been systematically disregarded: my presence has been ignored.

(c) The attitude adopted by certain authorities against the activities of the Criminal Investigation Department…”77

Craig and the cabinet perfunctorily thanked him “for the valuable service you have rendered at a critical period in our history.”78

However, the “Haddick document affair” had not yet been completely put to bed. Bates instructed his Parliamentary Secretary, Robert Megaw, and the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Samuel Watt, to conduct an inquiry into the matter. They reported to him the day after Craig accepted Solly-Flood’s resignation.

They said that a copy of the eight C1 battalion commandants’ original letter to Goodwin had come into the hands of Waters-Taylor on 16 November; he showed it to Solly-Flood the next day. The day before Haddick produced the controversial document at the commandants’ meeting, Waters-Taylor had given a copy of it to Solly-Flood. However, “No reports were furnished by the Military Adviser or the CID of this sinister agitation in the C1 force.”79

It turned out that Solly-Flood’s ultimate downfall had been due to his own failed machinations and inept scheming.

Summary and conclusions

In many respects, Solly-Flood was an unhinged lunatic.

He came into the role of Military Advisor with the mindset of a wartime general who was used to the British Army getting whatever it wanted in terms of new weapons and endless manpower. That mindset can be seen in his ludicrous demands for the C1 Specials: tanks, aircraft, artillery and the conscription of all northern males, including even nationalists.

His imperialist outlook meant that he simply viewed the empire as the source of an endless stream of riches, without realising that those riches came at a cost, not just for the empire’s subjects but, increasingly after the Great War, also in terms of maintaining their submission. He simply could not conceive of the Treasury in London as being other than a bottomless source of funding for the Specials; that blindness meant that his plans for the Specials were conceived in a fiscal fantasy completely divorced from reality.

His repeated proposals to re-occupy parts of the south signalled someone who refused to accept that the British Government had actually signed the Treaty and intended to uphold it.

He showed an absolute lack of political nous: not alone did he fail to develop alliances with key individuals like Bates, Spender, Wickham and Gelston, he soon alienated them, turning them into opponents. His disparaging tittle-tattling to Craig about Bates and the two policemen must also have reached their ears – Spender would have seen to that.

This meant that Solly-Flood’s only allies were his own staff, which left him overly reliant on and overly protective of the deservedly underappreciated CID, which employed criminals to produce lurid but laughably inaccurate “intelligence.” Although he came to realise that he was at risk of becoming the little boy who cried wolf, he did not change his approach, further undermining his own diminishing credibility.

His irritation at legal constraints was noted by Spender, but Solly-Flood had little regard for human rights in general, as evidenced by his calls for the introduction of death sentences with no right of appeal and the rounding up of nationalists into urban and rural concentration camps.

He had a similar disregard for local sensibilities, although at least he was even-handed in that respect, whether this involved putting a radio mast on a Catholic church or re-routing Orange parades on the Twelfth.

More critically, he had no understanding of unionist sensibilities around the Specials. Craig and his ministers were constantly alert to any prospect of a rift developing between themselves and their working-class supporters; therefore, the Specials provided not only security for Northern Ireland but also stability for the Unionist Party’s political base. For Solly-Flood to propose the abolition of the B Specials, the one class of the USC that Craig absolutely wanted to keep, was an act of utter folly.

The rejection of that proposal belatedly brought him to the single moment of accurate perception in his whole tenure as Military Adviser: that the Unionist government had progressed through 1922 by moving from a fear of “Sinn Fein,” to a fear of the Imperial Government, to a fear of “their own people.”

The title of this blog posts asks a rhetorical question: did the IRA shoot the wrong Military Adviser? In relation to Field Marshall Henry Wilson, the answer is “Yes” – he only held the role for a few weeks and had stepped down months before they killed him.

In relation to Solly-Flood, the IRA targeting him would have made no difference as he himself made no difference. In the eight months for which he held the role, every time he suggested anything to the Unionist government, the RUC or the British Army, they either ignored his advice or told him to mind his own business.

In Greek mythology, the curse placed on Cassandra was that she could accurately predict the future but that no-one would believe her. Solly-Flood’s curse – clearly a grave hindrance to any Military Adviser – was that he had no clue about the future and eventually, no-one would even listen to him any more.

Still, there was one possible consolation for him: presumably, the orgies had been enjoyable.

References

1 Chancellor of the Exchequer to Prime Minister, Northern Ireland, 19 July 1922, PRONI, Financing of Special Constabulary, CAB/6/51; Memorandum, unsigned, n.d., Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41; Prime Minister to Chancellor of the Exchequer, 19 July 1922, PRONI, Financing of Special Constabulary, CAB/6/51.

2 Conference of county representatives held by the Military Adviser, 24 July 1922, Military Archives (MA), Historical Section Collection (HSC), Conference general policy, HS/A/0988/04.

3 Ibid.

4 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 27 July 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/50.

5 James Craig to Marquis of Londonderry, 16 August 1922; Marquis of Londonderry to James Craig, 22 August 1922; PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

6 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 9 August 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/51; Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs to Cabinet Secretary, Statement – numbers mobilised, 18 October 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence September 1922 – December 1922, CAB/6/31.

7 Ibid.

8 Miliary Adviser to Cabinet Secretary and Ministry of Home Affairs, 12 August 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

9 Ibid.

10 James Craig to Arthur Solly-Flood, 21 August 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

11 Arthur Solly-Flood to James Craig, 22 August 1922, ibid.

12 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 12 September 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/52.

13 David McGuinness statement, Military Archives (MA), Bureau of Military History (BMH), WS417.

14 Ibid.

15 Permanent Secretary to Parliamentary Secretary, 8 September 1922, PRONI, Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, HA/32/1/271.

16 Military Adviser to Ministry of Home Affairs, 10 October 1922, ibid.

17 David McGuinness statement, MA, BMH, WS417.

18 Missing files from Military Adviser’s office, n.d., PRONI, Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, HA/32/1/271; for the files brought to Dublin by Woods, see: MA, Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents (BMHCD), Colonel Seumas Woods Collection, BMH/CD/310/01-16.

19 Establishments (Provisional) C1 Division, MA, BMHCD, Colonel Seumas Woods Collection, BMH/CD/310/05.

20 Navy, MA, BMHCD, Colonel Seumas Woods Collection, BMH/CD/310/08.

21 Paul McMahon, British Spies & Irish Rebels: British Intelligence and Ireland 1916-1945 (Suffolk, Boydell Press, 2011), p150.

22 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 12 July 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29; Military Archives, Military Service Pensions Collection, MSP34REF4970 Desmond Crean; Military Adviser to Prime Minister, 3 October 1922, PRONI, Criminal Investigation Department, CAB/8/G/1.

23 Notes from conference held at Constabulary Headquarters, 25 July 1922, MA, HSC, Conference general policy, HS/A/0988/04.

24 Cabinet Secretary to Prime Minister, 21 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

25 Minister of Labour to Prime Minister, 22 September 1922, ibid.

26 Charles W. Magill (ed), From Dublin Castle to Stormont: The Memoirs of Andrew Philip Magill 1913-1925 (Cork, Cork University Press, 2003), p70; PRONI, Reports on arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289. I am grateful to Paddy Mulroe who told me about this book and kindly shared his own research on the PRONI file.

27 PRONI, Reports on arrest and internment of individual gunmen, HA/32/1/289.

28 Ibid.

29 McMahon, British Spies & Irish Rebels, p154.

30 Cabinet Secretary to Prime Minister, 21 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

31 Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, 27 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence file, September 1922, CAB/6/30.

32 Military Adviser to Ministry of Home Affairs, 16 August 1922, PRONI, Report from Military Adviser on reorganisation of IRA units in Northern Ireland, HA/32/1/257.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 14 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

36 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 14 September 1922, ibid.

37 General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ulster District, to Cabinet Secretary, 16 August 1922, PRONI, Reduction in deployment of troops on streets of Belfast, HA/32/1/259.

38 Inspector General to Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, 21 August 1922, ibid.

39 Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 9 September 1922; Cabinet Secretary to Military Adviser, 21 September 1922; ibid.

40 Military Adviser to GOC, Ulster District, 21 September 1922, ibid.

41 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 15 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

42 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 16 September 1922, ibid.

43 Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 22 September 1922, PRONI, Reduction in deployment of troops on streets of Belfast, HA/32/1/259.

44 Cabinet Secretary to Military Adviser, 29 September 1922, ibid.

45 Prime Minister to Military Adviser, 19 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

46 Military Adviser to Prime Minister, Summary of Scheme for Formation of a Territorial Special Constabulary, 20 September 1922, ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Provisional Scheme for the Formation of a Territorial Special Constabulary in Ulster (Ulster Volunteer Constabulary), 20 September 1922, PRONI, Proposals of Military Adviser for protection of Northern Ireland including formation of an Ulster Volunteer Constabulary, HA/32/1/335.

53 Cabinet Secretary to Prime Minister, 21 September 1922, ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Prime Minister to Cabinet Secretary, 22 September, ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Minister of Home Affairs to Northern Ireland Government, 27 September 1922, PRONI, Financing of Special Constabulary and question of reductions, CAB/6/51.

62 Ibid.

63 Belfast News-Letter, 28 October 1922; Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), p175.

64 City Commissioner to Inspector General, 25 September 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence October 1922 – December 1922, CAB/6/31.

65 Inspector General to Ministry of Home Affairs, 3 October 1922 & Minister for Labour to Cabinet Secretary, 2 October 1922, ibid.

66 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 4 October 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/53.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Memo, “Secret” (no addressee), 5 October 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence October 1922 – December 1922, CAB/6/31.

71 Ibid.

72 Battalion Commandants to Commandant, C1 Special Constabulary, n.d. (November 1922), ibid.

73 Draft resolution, unsigned, n.d., PRONI, Future of Special Constabulary, CAB/6/52.

74 Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, Memorandum as to conference of the Commanding Officers of the C1 Constabulary, 23 November 1922, ibid.

75 Minister of Home Affairs to Prime Minister, 24 November 1922 & Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 29 November 1922, ibid.

76 Military Adviser to Prime Minister, 28 November 1922, ibid.

77 Military Adviser to Prime Minister, 5 December 1922, ibid.

78 Prime Minister to Military Adviser, 7 December 1922, ibid.

79 Parliamentary Secretary to Minister of Home Affairs, 8 December 1922, ibid.

Leave a comment