Edward Burke, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles (Merrion Press)

As this is a book review, I will refrain from giving repetitive references for quotes from the book; however, where other sources are mentioned, they will be detailed in the References section at the end. Estimated reading time: 20 minutes.

Introduction

This is the most important book to be written in decades about the events of this period in the entire north, not just in Belfast.

So prolonged, intense and savage was the political/sectarian violence in Belfast that it became one of the deadliest places in Ireland during 1920-1922. But at least Dublin, Cork and other sites of intense conflict during the War of Independence had five months of almost-peace between the Truce and the signing of the Treaty and nearly seven more months would elapse before the outbreak of the Civil War – Belfast had no such respite. Compared to the near-constant carnage in the city, the more episodic outbreaks of violence elsewhere in the north were a relative sideshow – thus, Belfast defined the north.

Michael Farrell largely based his 1983 book, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27, on the archives of the Government of Northern Ireland. While the scope of the book was not limited to Belfast or the Pogrom, the Specials’ actions in the city naturally featured prominently.

Jimmy McDermott’s Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms, 1920-22, published in 2001, provided an intimately detailed history of republican Belfast in those years. It seems scarcely credible now, but it was written before even the Military Archives’ Bureau of Military History witness statements had been made publicly available, let alone the vast treasures of their Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), thus making McDermott’s achievement all the more notable.

In Belfast’s Unholy War: The Troubles of the 1920s, published in 2004, Alan Parkinson mined the archives of local newspapers to tell the stories of those – overwhelmingly civilians – who were killed in the city. He also told the stories of some of those who killed them.

Now, twenty years later, a ground-breaking new book by Edward Burke, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles, introduces a hitherto-missing perspective, that of the British Army. Just as importantly, Burke provides the first in-depth analysis relating to other combatants who were responsible for killings – more about them later.

To do this, he has brought to bear exhaustive archival research in not just Belfast, Dublin and London, but also further afield, including France and Canada. In addition, he has somehow managed to unlock a crucial new source of evidence.

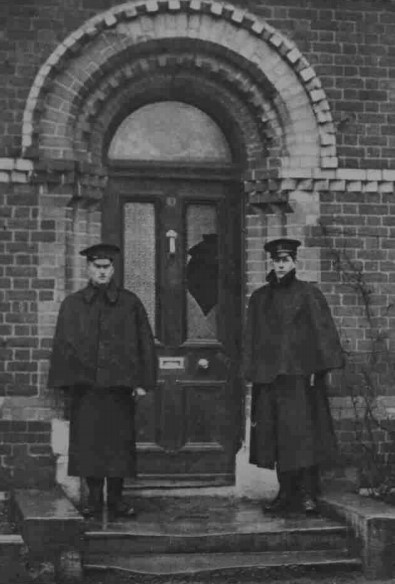

Troops of the Norfolk Regiment in Great George’s St

The 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment was the key unit of the British Army to be stationed in Belfast during the Pogrom; over time, troops from other regiments arrived to reinforce it, but for more than two years, it was the main garrison battalion in the city. The regimental museum in Norwich had previously been firmly closed to researchers but Burke clearly has formidable powers of persuasion, as he was able to secure access to reports written by the battalion’s Intelligence Officers while they were in Belfast. Tim Wilson has previously written about the fraught relationship between the Norfolk Regiment and Belfast loyalists but until now, no-one has ever done so based on the regiment’s own documents.1

Burke also provides a timely reminder that one of the benefits of the Decade of Centenaries has been the increased online availability of archival material. The MSPC is the most justly-celebrated example of this, but there is another such source which is extremely pertinent to this review.

The McMahon family killings

Burke’s point of departure is the night of 23/24 March 1922: a group of armed men smashed their way into 3 Kinnaird Terrace, the north Belfast home of a Catholic publican, Owen McMahon. Within minutes, McMahon and four of his sons, as well as his barman and lodger, Edward McKinney, had been shot and lay either dead or fatally wounded. Two of McMahon’s other sons survived the attack, as did his wife, daughter and niece.

The survivors were able to provide descriptions of the attackers: their leader was a man wearing a trench coat and cap, both light-coloured, who had “a round soft-looking face and very black eyes, he was about 5 ft 9 in in height.” He was clean-shaven and aged 30 to 35.

Policemen outside the McMahons’ home the morning after the killings (Illustrated London News, 1 April 1922)

As for the others, “‘Four of the five men were dressed in the uniform of the RIC [Royal Irish Constabulary] but from their appearance I know they are Specials not regular RIC.’”

The unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, rebuffed calls for a public inquiry into the McMahon killings and several others which took place on a single night less than ten days later in and around Arnon St, also in north Belfast. Instead, he insisted that a standard police investigation would be sufficient. When the Belfast city coroner eventually held an inquest into the McMahon killings, he did so without the interference of a jury, directed to do so by the Minister of Home Affairs, as provided for by the Special Powers Act. The inquest also just so happened to take place when the newspapers were on strike. This meant the verdict, that the victims’ fatal wounds were “wilfully inflicted by some member or members of an unlawful assembly,” was delivered into a void.2

Others sought to fill that void – most notably, the authors of a report prepared for the Free State government in 1924, often referred to as the “Nixon memo,” which described the activities of a police “murder gang” that had operated in Belfast, led by the controversial District Inspector John Nixon. It is very likely that the former Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, David McGuinness, at least contributed to the report – by 1924, he was an officer in the Defence Forces’ Office of Border Intelligence.3

District Inspector John Nixon

The Nixon memo stated that Constables Sterritt and Gordon were the two policemen who took a sledgehammer from a workmen’s hut in Carlisle Circus that was used to break down the McMahons’ front door; both men were stationed at Brown’s Square Barracks, Nixon’s headquarters. However, neither the memo nor the surviving McMahon family members specified Nixon as having been the man in a trench coat who had led the killers, although he was named as being the leader of the groups that committed other “murder gang” killings elsewhere. No-one was ever charged with the killings at Kinnaird Terrace.

New evidence

In chapter 2, titled “Belfast’s Descent,” Burke describes the context in which the McMahon family killings took place.

He points out that by July 1921, British officials had already “arrived at an uncomfortable conclusion: the police, specifically the ‘B’ Class of the Special Constabulary, were instigating rather than suppressing sectarian violence.” By the spring of 1922, there was a complete “collapse in relations between the Special Constabulary and the soldiers” – he provides instances of actual conflict between them: “The Norfolks also came under attack from special constables in Nixon’s district.”

It is at this point that Burke’s access to the Norfolk Regiment’s archive allows him to introduce further important new evidence: “According to British military intelligence, several groups of loyalist paramilitaries were closely linked to, or tolerated by, the police. Some were conducting intelligence work, others were involved in reprisals, including murder, and some were doing both.”

The most significant of those paramilitaries were the Ulster Imperial Guards, who staged an initial show of strength by holding a series of church parades in November 1921 and soon claimed to have over 21,000 members. Nor were they a mere stage army: “Between November 1921 and April 1922 at least six members of the Imperial Guards were killed during fighting in Belfast.” One of those six was killed by a corporal of the Norfolk Regiment – hours later, the Imperial Guards retaliated by killing a Norfolks private.

York St Imperial Guards in the funeral procession of a fellow-member, Herbert Hazzard, who was killed by the British Army (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 18 March 1922)

The Norfolks were not alone in being met by loyalist violence – troops from other regiments came under similar attack in the west and east of Belfast. I will return to this subject in a future blog post, but by spring 1922, men wearing the king’s uniform were not only frequently being threatened with being shot, but were actually being shot by men who professed loyalty to the same king and who had recently worn the same uniform.

Michael Farrell has fittingly described the British Army as behaving during the Pogrom “with fine impartiality.” Burke superbly demonstrates how that impartiality enraged both the Specials and the Imperial Guards, neither of whom had any compunctions about killing anyone who got in their way.4

Old evidence

Burke’s chapter 3 is titled “Aftermath” and introduces Owen McMahon’s five brothers, all of whom also owned pubs around Belfast.

However, it mainly focuses on the Arnon St killings which took place not long after those of the McMahons and which were investigated by both the Norfolk Regiment and the southern Provisional Government. Michael Collins’ brother-in-law, Patrick O’Driscoll, was his investigator in Belfast – O’Driscoll gathered statements from sympathetic Catholic policemen and from eye-witnesses to the Arnon Street killings. He and the Norfolks’ Intelligence Officers came separately to the same conclusion: that the killings in Arnon St had been perpetrated by regular police and Specials based in Brown’s Square Barracks – Nixon’s fiefdom.

The following chapter, “A Terrible Victory, ” charts the final stages of the Pogrom. In May, the IRA launched its ill-fated “northern offensive” but by the summer, “The contest of violence was over. The Special Constabulary extended its control over the city…”

However, there were still divisions within unionism – one that continued to fester involved Nixon, who seethed at having been overlooked for promotion. He enjoyed strong support from the Specials and the Orange Order, thus making him a political threat to Craig’s government. While many IRA members were the subjects of an internment file in the north and a Military Service Pensions file in the south, Nixon was probably the only policeman to achieve the dubious distinction of having a file kept on him by both governments.

Burke charts Nixon’s later career, from his dismissal from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in 1924 for forbidden political activity through to his election as an independent unionist MP in 1929 – “Between 1929 and 1937 Nixon voted with the government on only fourteen occasions.” Along the way, he took and won two libel cases against a newspaper and a book publisher who stated that he had been responsible for the McMahon killings. Despite those legal victories, Belfast nationalists continued to believe that Nixon’s hands were stained with the McMahons’ blood.

However, that belief and much else of what they believed about Nixon were misplaced. Burke demonstrates this to devastating effect in a startling chapter, “The Brown’s Square Gang.”

Nixon, Sterritt and Gordon were all named in the Nixon memo as members of what Belfast nationalists in general, not just the IRA, had come to term the police “murder gang.” The same three men were also identified by the Norfolk Regiment as belonging to what its Intelligence Officer described much more specifically as the “Brown’s Square Murder Gang.”

Burke has methodically trawled through the RIC service records of twenty-six IRA-identified members of the “murder gang,” along the way establishing that twenty of them came from what would become the Free State; three of the twenty-six were Catholics. This deep analysis allows him to demonstrate that Nixon could not have been involved in the first attack launched by the “murder gang” in September 1920, in which Ned Trodden, John McFadden and Seán Gaynor were killed – at that point, Nixon was still stationed in Lisnaskea in Fermanagh.

On 10 June 1921, the IRA killed Constable James Glover in Cupar St off the Falls Road – they had established that he was a member of the “murder gang.” Two nights later, three Catholics, Alex McBride, William Kerr and Malachy Halfpenny were killed in what was widely seen as a retaliation by the “murder gang.”

Burke completely demolishes this view, showing that the three were indeed killed by a police murder gang but not by the “murder gang” as it has previously been defined. In the process, he also demolishes a long-established belief that the Auxiliary Division of the RIC was not deployed in action in Belfast.

Q Company of the Auxiliaries were a specialised unit, set up to search ships arriving in Ireland in order to block the smuggling of arms and ammunition destined for the IRA; over half the members of Q Company were from a naval background. Although its headquarters was at the London North Western Railway Hotel on North Wall in Dublin’s docklands, detachments were sent to other ports along the east coast – including one stationed in Musgrave St Barracks in Belfast. Their activities were not limited to searching shipping.5

Q Company Auxiliaries in their distinctive hats, pictured outside their Dublin headquarters after it was attacked (© www.theauxiliaries.com)

The Regulation of Order in Ireland Act 1920 allowed for coroners’ inquests to be replaced by military Courts of Inquiry. The Law Society of Ireland might reasonably be expected to have an informed legal opinion about the conduct of such courts; an article in the Law Society Gazette stated, “It is probably fair to say that the intent was to distort or hide the truth, and thus create additional breathing space for the actions of the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans.”6

Military Courts of Inquiry were held into the killings of McBride, Kerr and Halfpenny. Burke uses evidence gathered by those courts to show that Auxiliaries stationed in Belfast were responsible for at least two of those killings.

Elizabeth McBride testified that when an open-top lorry pulled up outside their home off the Cliftonville Road, “The majority [of the men in it] had soft caps, hanging over on one side.” Others were wearing police caps. Neither of the two men who seized her husband seemed to know where the nearest military barracks was, even though they claimed they were taking her husband there. His body was found off the Ballysillan Road the next morning.

Alice Kerr was staying with her brother William’s family on the Old Lodge Road. When she opened the front door, three men rushed upstairs to the bedroom of her brother and his wife, who testified: “One was a tall fair man, he wore a tam’o’shanter…something like a policeman’s coat but not an RIC coat, and khaki trousers. He also had a pair of goggles hitched up on his cap. He had an English accent…” Another man wore a trench coat but had a Belfast accent. One of the abductors told Alice, “You won’t see him again.” Kerr’s body was discovered off the Springfield Road the next morning.

Malachy Halfpenny’s sister Winifred opened the front door of their home in Herbert St, Ardoyne, to a man with a Belfast accent: “He had on a khaki cap with black glazed peak and shiny top. There were goggles on the cap’s peak.” As Burke points out, “This was not a description of a regular Belfast RIC policeman. It more closely resembled a driver from the RIC Transport Division.” Neighbours testified that the lorry was like the ones used by the Specials and that the men in it were wearing civilian clothes; one saw it stopping outside Ardoyne fire station and then heard shots. Significantly, “Constable James Glover’s brother Samuel lived at Ardoyne fire station. Malachy Halfpenny was shot dead outside Samuel Glover’s house at Ardoyne fire station on 12 June, the night before James’ funeral. The reprisal message could not have been clearer.”

An Auxiliary officer named James also testified: “At the inquest he was described as second-in-command of an Auxiliary platoon…he had two vehicles out on patrol until 12.15am…Accompanying James and his men was a detachment from the RIC Transport Division, Gormanstown Camp, who were also based in Musgrave Barracks on the night of the murders.” Lieutenant E.M.V. James was an officer in Q Company; naturally, he said that his men had returned to the barracks by the time the killings happened.7

Lieutenant E.M.V. James of Q Company of the Auxiliaries (© www.theauxiliaries.com)

The evidence presented by family members at these Courts of Inquiry flatly contradicts the claims in the Nixon memo and instead establishes that responsibility for these killings lay with the Auxiliaries, acting alongside local Specials. The military courts wanted to conduct an identity parade in Gormanstown but lacked legal powers to do so; meanwhile, despite detailed questioning, “the RIC was stonewalling the army.” Ultimately, the courts came to the verdict that each of the three men was killed by “some person or persons unknown.”

Burke voices a somewhat harsh criticism that “The Nixon memo ignored evidence given by the families at respective military inquests.” However, that evidence was not publicly available as the military Courts of Inquiry were held in private, with no press present. While the IRA’s Intelligence Officers could always have tried to speak to the families or their lawyers after the hearings, unlike previous victims of the “murder gang,” these three men had no republican connections so access to the families would have been more difficult. Nor would the network of sympathetic policemen in RIC barracks – including Brown’s Square – have been as fruitful as usual in terms of intelligence, given that the killers were not drawn from the regular RIC.

No such charity can be extended in relation to current researchers. It was not until reading this jaw-dropping chapter that I renewed a subscription to findmypast.ie, only to discover that the evidence presented at these inquests is now available online and that I had simply failed to keep myself up to date. Mea culpa.

Burke also challenges other parts of the Nixon memo, but not in an effort to exonerate the discredited policeman. On the contrary, he highlights two attacks that the “Brown’s Square Murder Gang” attempted to perpetrate but which were thwarted, neither of which were mentioned in any IRA or Provisional Government report, but which the Norfolk Regiment learned about, one in Ardoyne and one off the Oldpark Road – the latter involved Nixon himself.

In disproving some assertions of the Nixon memo, Burke’s objective is to guide us to a crucial realisation: “Nixon’s ‘gang’ was not the only reprisal force in Belfast. There were other loyalist killers in Belfast who had their own motives and an even greater capacity for atrocity.”

Loyalist killers

Chapter 6 is aptly titled “Taking a Delight in Killing,” as it introduces some of those killers.

The best-known was “Buck Alec” Robinson, believed by the RUC to have carried out at least three killings and to have attempted others. But Robinson had accomplices in north Belfast and counterparts elsewhere in the city. Some were B Specials or, like him, C1 Specials; some were members of the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), a particularly violent paramilitary group in east Belfast; some were members of the Imperial Guards. Some even had dual membership of the Specials and one of the paramilitary groups – the north Belfast C1 Specials, in particular, recruited heavily from among the Imperial Guards.

In late 1922, the northern government interned sixteen such loyalists. But apart from suspected involvement in killings, those internees shared something else in common. Burke details how readily many of them were given support by important unionist politicians.

When Robert Simpson, chairman of the UPA, was interned, four unionist MPs and the unionist Lord Mayor of Belfast all petitioned for his release. After B Special Samuel Ditty was interned, a unionist MP at Westminster “testified to his innocence and ‘excellent character.’” “Buck Alec” Robinson hit the jackpot – his uncle was William Grant, unionist MP for north Belfast; a mere month after interning Robinson, the northern government paid his fare to move to England.

The pattern is clear: unionist MPs were quick to provide political cover for the activities of loyalist paramilitaries.

“Buck Alec” Robinson

By introducing these loyalists into the narrative, Burke succeeds in taking the focus further away from Nixon as the most likely perpetrator of the McMahon family killings. But he points out that “Without a greater understanding of motive, knowledge and opportunity, it is impossible to know who or which group… should be treated as the principal suspect or suspects for the attack on the McMahon family.”

That only begs the question: if Nixon or the interned loyalists didn’t do it, who did? Burke has someone in mind.

The suspect

In the book, he names a man who does seem to be very likely to have led the gang that killed the McMahons.

David Duncan had been in the Royal Irish Rifles during the Great War. He was wounded in France and survived the slaughter at Gallipoli, after which he was sent to Salonika, where “the abuse of alcohol – easily sourced from local villages – was a persistent problem for 10 (Irish) Division, as it was for others.” After being dismissed from the British Army on disciplinary grounds, he re-enlisted to serve with the army’s expeditionary force to Russia, one of several foreign armies fighting there alongside the Whites against the Bolsheviks in the Civil War. When that campaign ended in ignominious failure, he then joined the Auxiliaries, only to be dismissed for misconduct again on 20 October 1921.

Nine days later, he was photographed with other Imperial Guards officers at a parade in north Belfast.

Imperial Guards officers at a parade off York St on 29 October 1921; David Duncan is third from the right (Belfast Telegraph, 1 November 1921)

On 24 November, Patrick McMahon, a brother of Owen, identified Duncan as the man who had attempted to kill him in his York St pub. The following day, a shopkeeper was killed in his shop in Little Patrick St, just off York St; Duncan was named as one of the killers by an eyewitness who had served in the same regiment as him in Salonika.

When Duncan was brought to trial on charges of murder and attempted murder, the jury was given what Burke describes as a “risibly selective account of the role played by the Imperial Guards.” Despite the apparently watertight evidence of two eyewitnesses, Duncan was acquitted. Now, he had not only an acquittal but also a grudge against Patrick McMahon – a possible motive for killing.

In its publicity for this book, Burke’s publisher describes it as a “cold-case investigation” and Burke’s dogged detective work has led him to examine previously-overlooked sources: before now, no-one had delved into the records of Belfast’s pub licences in order to understand the context for some of the violence in the city, but his painstaking research allows Burke to paint fascinating and exquisitely detailed pictures of the intricate connections at play in these events. For instance, in 1910, Patrick McMahon bought a pub from a man named William Bickerstaff; by 1922, Bickerstaff was the commandant of the B Specials in Brown’s Square Barracks; he also owned a meat-curing business across the street from the barracks; next door to his business was a pub owned by Rosaleen Purdy; the Purdys were the McMahons’ next-door neighbours in Kinnaird Terrace.

Burke uses the same meticulous research to reveal a similar network that surrounded Duncan. Key among them was Captain Sam Waring, a senior Imperial Guard and adjutant of the north Belfast C1 Specials; Waring’s uncle had been a close friend of Nixon but was killed in February 1922, so Waring probably wanted revenge. James Lyle was another important north Belfast Imperial Guard: while in the British Army, he had served during the Easter Rising in 1916 alongside Captain John Bowen-Colthurst – the man who ordered the execution of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. As Burke rightly says, “Lyle was an individual untroubled by, and involved in, murderous reprisal.”

But these and various others who Burke details turn out to be red herrings. He says that Bickerstaff, Waring and Lyle lacked a clear motive for wanting to target the McMahons, although here, he is perhaps guilty of over-looking the simplest yet crudest potential motive: the McMahons were Catholics. But much more importantly, none of these men fits the description of the killers’ leader offered by the survivors at Kinnaird Terrace.

Nor does Nixon: the leader was clean-shaven, aged 30-35 and spoke in a Belfast accent, while Nixon had a moustache, was at least ten years older and was from Cavan.

However, Duncan does match the description of the leader in terms of age profile, height, facial features and accent; his brother lived in Spamount St in the New Lodge, a few hundred metres from Kinnaird Terrace and so a conveniently close place to hide afterwards. His accomplices could easily have been drawn from among the York St Imperial Guards who were also members of the Specials – the McMahon survivors specified that the four other killers were Specials, not regular police.

While Burke has built an exceptionally strong case against Duncan, would it stand up in court? Probably not. Although Duncan may well have been the McMahons’ killer, he had already beaten charges of murder and attempted murder even though eyewitnesses had positively identified him.

As well as being an Imperial Guard, Duncan was also a C1 Special. He applied to join the regular RUC in September 1922, but his application was rejected – shortly afterwards, he threatened to shoot an RUC sergeant on the York Road. He later spent a period in the French Foreign Legion and became a violent, alcoholic bigamist.

He emigrated to Canada in 1929. Six years later, he was confined to a psychiatric institution where he spent the final four years of his life grappling with paranoid delusions, imagining voices from various places in his past threatening him – irrespective of their national origin, these voices always had Irish accents.

If nothing else, this is a strong argument for the existence of karma.

Summary

No work of history is flawless, although this one comes closer than most. I found one thing irritating about it, but it is more in the nature of a technicality: sometimes the fruits of Burke’s prodigious research are let down by less-than-fastidious footnoting. For example, no reference is given for the surprising statement that Auxiliaries were involved in shooting up nationalist districts on the Falls Road on 10 July 1921; the date is significant, as it marked Belfast’s Bloody Sunday, when police and loyalists took revenge for the IRA’s killing of an RIC officer the previous night. The statement came as news to me and I would have liked to have seen a source for it.

However, Burke’s book accomplishes everything that you could wish for from a new work of history: it introduces compelling new archival evidence, it successfully challenges received wisdom and it brings our understanding of the events to an unprecedented level.

By unlocking the archive of the Norfolk Regiment, he has been able to place the British Army firmly onto the Belfast stage alongside the Specials, IRA and civilians who have already been written about by Farrell, McDermott and Parkinson respectively. Burke has by no means told the entire story of the British Army during the Pogrom – there are other regiments whose archives have yet to be explored – but he has made a significant start and left a huge signpost for future researchers to follow.

Not content with that, he has also absolutely shredded the veil of invisibility behind which the various loyalist paramilitary groups had hidden until now, skulking in the wings. They, along with the Auxiliaries, have at last been dragged into the spotlight to face the glare of history.

Burke has managed to simultaneously repudiate some of the claims made about Nixon while not diminishing Nixon’s status as one of the most monstrous men to plague Belfast in those years, one who certainly directed and covered up for extrajudicial killings perpetrated by the regular police and Specials, even if he was too wily to leave his own fingerprints at the scenes. Not all of what was believed about Nixon was well-founded, but much was. But importantly, Burke encourages us to look beyond the usual suspect and see that Nixon did not act either alone or uniquely. By doing so, Burke introduces valuable nuance to displace previous simplistic narratives.

No-one will ever prove definitively who carried out the slaughter in Kinnaird Terrace. But Burke has done a better job than anyone yet of proving who most likely did, as well as proving who did not.

With this brilliantly crafted and structured book, he has made a substantial addition to the body of knowledge about the Pogrom – we now know much more about the main players in terms of both the broad picture and the details of particular individuals and events.

I really wish I had written this book – you should definitely read it.

References

1 Tim Wilson, ‘“The most terrible assassination that has yet stained the name of Belfast”: the McMahon Murders in Context’, Irish Historical Studies, Volume 37 Issue 145 (May 2010), p83-106.

2 Ibid.

3 Captain David McGuinness to Director of Military Intelligence, 29 March 1924, Military Archives, Historical Section Collection, Records of 3rd Northern Division, HS/A/0988/05.

4 Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland – The Orange State (London, Pluto Press, 1980), p29.

5 https://www.theauxiliaries.com/companies/q-coy/q-coy.html

6 Gerard Quinn, ‘Legalised illegality by Crown forces’, Law Society Gazette, 6 November 2020, https://www.lawsociety.ie/gazette/in-depth/eileen-quinn

Leave a comment