Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

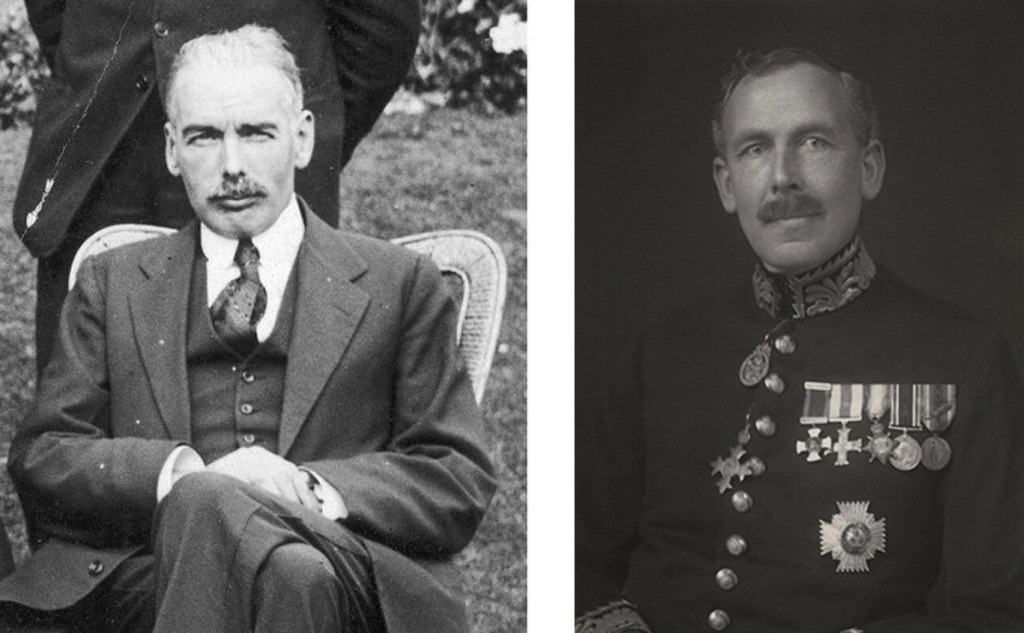

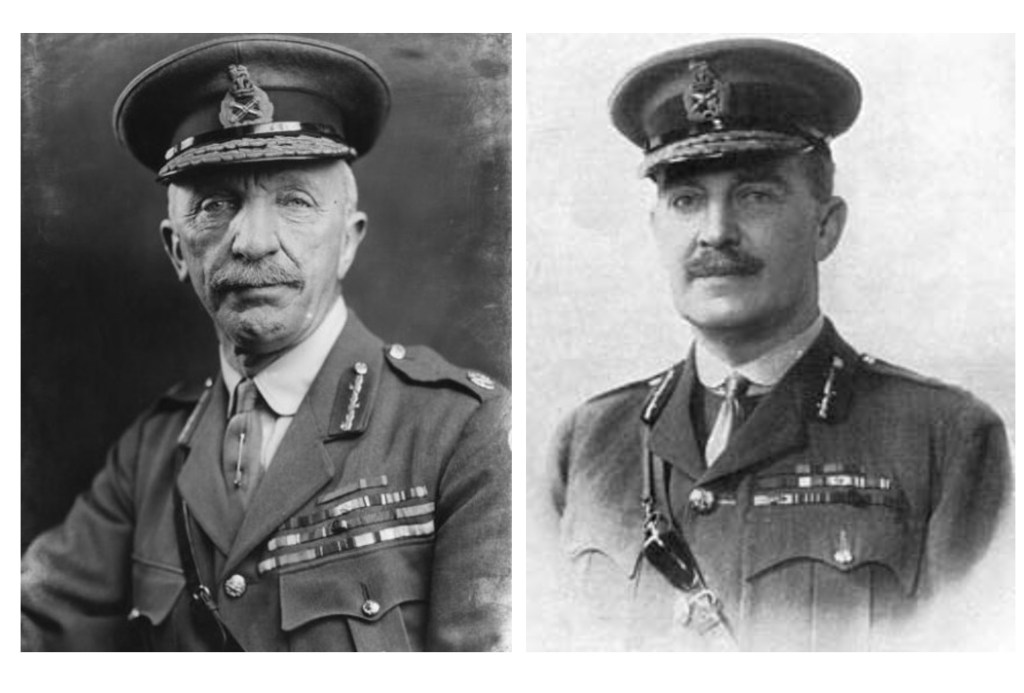

Field Marshall Henry Wilson

Although Henry Wilson was born in Longford in 1864, his father’s family had roots in Antrim going back hundreds of years. This Ulster connection took on a more contemporary dimension when the Home Rule crisis erupted:

“In 1913, when Ulster unionists had begun to organise armed opposition to the threat of home rule, Lord Roberts, who had been asked to take command of the UVF, suggested that Wilson might become his chief of staff…The following year, throughout the crisis precipitated by the Curragh incident, when sixty cavalry officers resigned their commissions rather than accept orders that they thought were intended to coerce Ulster into an all-Ireland parliament, Wilson worked behind the scenes in support of the Ulster cause, and kept leading British opposition politicians informed of developments.”1

Wilson became Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) in February 1918 and remained in that role until February 1922 – thus, he was Britain’s most senior general throughout the War of Independence and until after the signing of the Treaty: “He was especially intransigent regarding Ireland, where he unremittingly advocated a stern policy of repression to counter the violent nationalist challenge of 1919–21…Vainly he proposed a fully militarised offensive against the IRA, with the government taking open responsibility for formalised reprisals and collective punishments.”2

Approaching his retirement as CIGS, he accepted a Unionist Party offer of a seat at Westminster and three days after resigning, was elected unopposed for the constituency of North Down.

Although he was not responsible for the Special Powers Act – the bill had already been drafted by mid-March, before he was appointed Military Adviser – nationalists still identified him with its genesis: “Yesterday the Belfast parliament initiated a measure to put the cat-o’-nine-tails in the hands of Sir Henry Wilson to flog northern nationalism into submission.”3

Field Marshall Henry Wilson

Months after stepping down from his role of Military Adviser, Wilson continued to be associated in nationalists’ minds with the actions of the Unionist government; Ronan McGreevy has highlighted this in his biography of Wilson: “Collins blamed the clashes at Belleek and Pettigo [in late May and early June] on Wilson and his supporters.”4

However, Wilson did remain in contact with the Unionist government afterwards: he attended cabinet meetings on 19 April and 26 May and he continued to correspond with Prime Minister James Craig. His last letter to Craig would appear to be a handwritten note, dated 31 May, in which he declined an offer from the West Belfast Unionist Association to stand as their candidate in the next election to the Northern Ireland Parliament: “I could not possibly carry out the two duties of member for the Northern and for the Imperial Parliament at the same time, and I feel that if I can be of any use anywhere it is in the Imperial Parliament.”5

On 22 June, Wilson was shot dead on the doorstep of his London home by two former British soldiers who were members of the city’s IRA, Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan. The men’s getaway car failed to show up, so they attempted to flee the scene on foot, but were slowed by the fact that O’Sullivan had a wooden leg as a consequence of being wounded during the Great War. They were soon surrounded and beaten by an angry crowd and arrested by policemen.

Given that they had been identified by eye-witnesses and were caught while trying to make their escape, it was inevitable that Dunne and O’Sullivan would be found guilty of murder, which they were after a trial that lasted less than a day. They were both given the death penalty. Dunne had intended making a statement to the court after the prosecution had completed its presentation of evidence, but was prohibited from doing so by the trial judge, who dismissed it as “a political manifesto” and “anarchic propaganda.”6

However, the statement was published in the Irish Independent two days after the pair were hanged. In it, Dunne did not mention – for obvious reasons – that because Wilson was CIGS, an inveterate imperialist and obdurate opponent of the Irish revolution, he had been targeted for assassination by the London IRA prior to the signing of the Truce in July 1921 and that they had continued to target him in 1922.7

Reginald Dunne

Instead, Dunne emphasised Wilson’s involvement with the Unionist government as a motive for the killing, but he completely overstated the extent of that involvement:

“…the Irish nation knows him…as the man behind what is known in Ireland as the Orange Terror. He was at the time of his death the military advisor to what is colloquially called the Ulster Government, and as military advisor he raised and organised a body of men known as the Ulster Special Constabulary, who are the principal agents in his campaign of terrorism.”8

In reality, the Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) had been created in October 1920, a year and a half before Wilson’s appointment; nor was he still the Military Adviser when he was killed. Dunne went on:

“ … it is well known that about 500 men, women and children have been killed within the past few months, nearly two thousand wounded , and not one offender brought to justice. More than 9,000 persons have been expelled from their employment; and 23,000 men, women and children driven from their home…Sir Henry Wilson was the representative figure and the organiser of the system that made these things possible.”9

Dunne had an inflated view of Wilson’s contribution as Military Adviser – in truth, this was both brief in duration and minimal in impact.

Wilson as Military Adviser

At a meeting of the Northern Ireland Cabinet on 13 March, Craig informed his government colleagues that he had invited Wilson to act as their Military Adviser and that Wilson had accepted.10

He thus became the first person in the world to be appointed as Military Adviser to a government which had no army and could not have one – the Government of Ireland Act 1920 reserved defence as a function of the British government.

L: Richard Dawson Bates, Minister of Home Affairs; R: Wilfrid Spender, Cabinet Secretary

Four days later, Wilson travelled to Belfast to attend a meeting with Richard Dawson Bates (Minister of Home Affairs), his Permanent Secretary, Samuel Watt, Wilfrid Spender (Northern Ireland Cabinet Secretary) and Charles Wickham, the Divisional Commissioner of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). The minutes of the meeting show that Wilson expressed views that probably surprised his listeners and would even have astonished Dunne.

The discussion mainly revolved around who should or should not be allowed carry arms – Wilson insisted that this should be limited to men who took the oath of allegiance, were members of the Specials and were “of sufficiently good character to be admitted.”11

As regards the Specials, Wilson advocated that, “A new proclamation might be issued notifying all the inhabitants of the Six Counties to join this force, irrespective of class or creed…Encouragement should be given to Catholics to join equally with the other religions.”12

Wilson also expressed trenchant views on loyalist paramilitary organisations such as the UVF:

“The difficulties in connection with allowing some of the private organisations now in the Six Counties to carry arms were mentioned, but Sir Henry Wilson expressed the view that this government should not temporise or give in to such organisations if they determined the ignore the regulations of the government. Either the government governs or it will be governed.”13

Given that Spender had been the UVF’s Quartermaster General prior to the Great War, this must have been particularly uncomfortable for him to hear.

The precise nature of what were delicately described as “difficulties” became apparent a few days later – the Unionist government had been depending on another loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Imperial Guards, to provide some of its illegally-held weapons in order to arm a new C1 Class of Specials; the problem was that the government could hardly accept a donation of some of the group’s weapons and then set about trying to locate and seize the remainder. However, a solution had been found – the C1 Specials were now going to be armed with UVF weapons that had been stored at its arsenal in east Belfast:

“The fact that the Tamar Street arms were now available made it unnecessary to rely on the Imperial Guards for the supply of arms for that C2 [sic] force; in view of the changed situation in this respect it was determined that the previous agreement should be varied in accordance with the Field Marshal’s recommendations.”14

By using the weapons of its preferred paramilitary group, the government therefore neatly avoided becoming beholden to another paramilitary group that lay further from its influence or control.

In a memo to Craig later the same day, which was then printed in the press on 20 March, Wilson noted “the state of unrest, suspicion and lawlessness, which has spread over the frontier into the Six Counties of Ulster.” He said that “The dangerous condition which obtains in the 26 Counties will increase and spread unless:- 1. A man in those counties rises who can crush out murder and anarchy, and re-establish law and order.” Wilson clearly did not view Michael Collins as being up to this task.15

He continued: “2. Great Britain re-establishes law and order in Ireland. Under Mr. Lloyd George and his government this is frankly and laughably impossible, because men who are only capable of losing an empire are obviously incapable of holding empire, and still more incapable of regaining it.”16

Wilson promised to make separate detailed proposals in relation to four general points of advice which he offered:

“(a) Considerable alterations in the command and administration of all your armed forces – RIC, ‘A’ Specials, ‘B’ Specials, etc.

(b) Re-class and re-adjust the various categories of our police, and greatly strengthen some of them.

(c) Re-draft your laws for the carrying of arms.

(d) Take increased powers for rapid and drastic action against the illegal importation and carrying of arms, bombs, etc.”17

It is worth highlighting that the very first point which Wilson raised contained a barely-veiled criticism of two of the most senior policemen in Northern Ireland, Wickham and the RIC City Commissioner for Belfast, J.F. Gelston.

Wilson’s detailed plans never materialised, as within two weeks of writing this memo, he had been replaced as Military Adviser by his own nominee, Major General Arthur Solly-Flood.

The appointment of Major General Arthur Solly-Flood

Despite an almost-disastrous start to his Great War career – “in August 1914 he almost killed a troop of British 19th Hussars, mistakenly identifying them in bad visibility as Germans” – Major General Arthur Solly-Flood finished the war in command of the 42nd Division on the Western Front.18

But he was not Wilson’s first choice as his successor.

Major General Arthur Solly-Flood

Wilson initially approached someone referred to only as “P de B” in his correspondence with Spender. Edward Burke has suggested that this refers to General Percy Pollexfen de Blaquiere Radcliffe, the Director of Military Operations at the War Office in London; it certainly seems implausible that there was a second general so exotically named that it required abbreviation to the same set of initials. However, “P de B” declined the invitation – Solly-Flood was the next prospective candidate on Wilson’s list.19

His appointment as Military Adviser was duly ratified by the Northern Ireland Government at a cabinet meeting on 1 April 1922.20

Later that month, Craig clarified Solly-Flood’s responsibility: “Major General Solly-Flood is in supreme control of all the Constabulary forces of Northern Ireland for all purposes, but he may delegate to Colonel Wickham such powers as he thinks fit, more especially in regard to the Royal Ulster Constabulary.” Craig went on to warn against duplication of intelligence work between the regular police and Specials, but left Solly-Flood in charge of putting in place whatever he felt was the best arrangement for this function.21

Wickham must have resented the new development, as it meant that instead of reporting directly to Dawson Bates, he would now be subordinate to Solly-Flood.

However, Wickham had his own enemies within unionism, partly reflecting the fact that, as an Englishman, he was seen as an outsider and therefore not entirely trustworthy – on 10 April, the owner of a shirt factory in Derry had written to Spender castigating the Divisional Commissioner: “Now, speaking for the ‘B’ Class he never impressed me as man having any brains and does not understand the requirements of Ulster…I personally look upon Wickham and his whole staff in Waring Street as an expensive and inefficient department.” Later in the year, the Minister of Education, Lord Londonderry, would bluntly tell Craig, “As to Wickham, I would do my best to persuade you that he is not nearly a big enough man for the post.”22

Solly-Flood had to set about recruiting a staff, all of whom were to be military officers, as “Craig believed that securing the services of a few army officers of standing would improve the organisation and discipline of the USC.” Not alone had Solly-Flood no staff, he lacked even secretarial support and was reduced to typing his own memos: “At present I have no staff, so excuse typewritten letter.”23

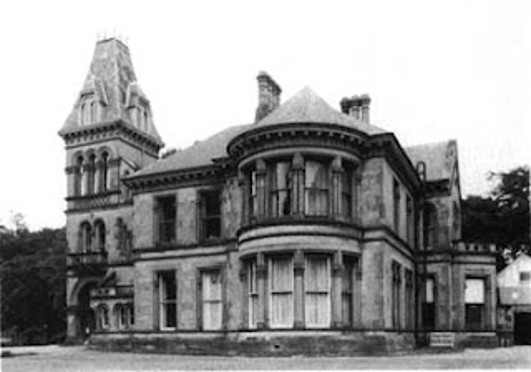

Danesfort House

The original intention was that he and his staff would live and work at Danesfort House, a mansion on the Malone Road in south Belfast (now home to the United States Consulate) which also had enough space to provide offices and bedrooms for clerks and servants.

Apart from work, Danesfort House may also have been the setting for some other, more recreational, activities which might not necessarily have met with the approval of Solly-Flood’s Calvinist employers. Andrew Magill was a civil servant who transferred from Dublin to Belfast to take up a role in the Ministry of Home Affairs; according to his memoirs, “They took an expensive house in the Malone Road for their headquarters, and of course the most lurid tales of orgies there began to circulate through Belfast…”24

In early June, Ernest Clark, the Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Finance, complained to Solly-Flood that much of the building had been given over to the latter’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) instead of them being based at police headquarters in Waring St in the city centre. Solly-Flood insisted that the work of his CID was too important to be interrupted by transferring them to Waring St and so he requested that he and his staff be given the use of Cabin Hill, a mansion near Stormont, which until recently Craig had been using as a residence. It would be interesting to know whether either Craig or Solly-Flood realised that the original farmhouse at Cabin Hill had been built in 1787 by Samuel McTier, the first president of the Belfast United Irishmen.25

Despite the initial lack of staff, Solly-Flood got to work quickly and at a cabinet meeting on 19 April, presented a “Preliminary report on the steps necessary for preservation of law and order within the Six Counties, and the city of Belfast.” It is unclear to what extent these proposals were entirely his own creation or simply represented him putting flesh on the bones that had been initially sketched out by Wilson; Wilson attended this cabinet meeting to give his imprimatur to Solly-Flood’s proposals.

Solly-Flood clearly shared his predecessor’s imperialist outlook, opening his assessment:

“Owing to the various malign influences which are now at work throughout the Empire – such as strikes, revolutionary, communistic and Bolshevic [sic] agencies, besides political and religious strife, it is highly probable that the shock will fall at time when the regular troops of His Majesty’s Government have left Ulster.”26

Leaving nothing to chance, he identified three potential sources of danger: “(a) Internal trouble, or malicious injury and damage, (b) Invasion from over the frontier from the south and west, (c) The unforeseen.”27

He was particularly exercised by the meandering vagaries of the border and proposed occupying two large swathes of territory in the south – the “Monaghan salient,” which would have cut off the whole northern part of the county stretching from Clones to Castleblayney, and a strip extending across the width of Donegal, seizure of which would completely isolate it from the rest of the Free State:

“The Donegal promontory on the western flank must be closed up at its mouth to deny ingress and egress to hostile forces…it will necessitate two distinct forces, one facing south about the line Belleek and Bundoran, and one facing north about the line Pettigo on Lough Erne, Coolmore on Donegal Bay.”28

Specials guarding the border

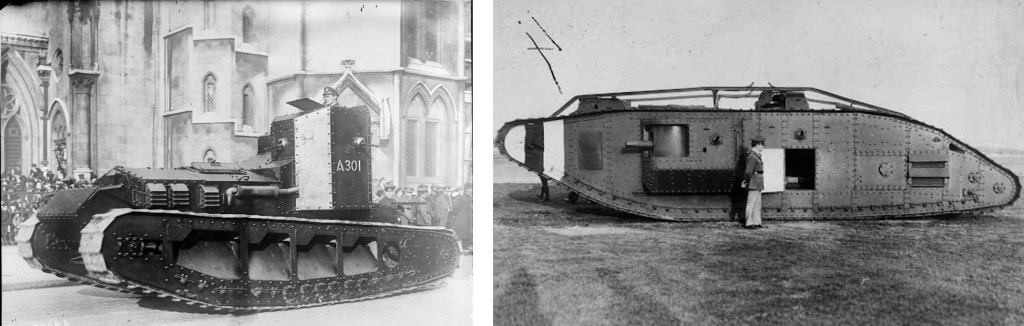

At that time, Solly-Flood had at his disposal 3,000 regular RIC, supplemented by 5,000 A Specials, 20,000 B Specials and 7,000 C Specials; however, he felt that the RIC and B Specials were already fully committed in dealing with republican opponents, leaving only the 12,000 As and Cs to defend against cross-border attacks. To do the latter properly, he would need “31,000 rifles,” although this estimate might be modified “if mechanical inventions can be procured, such as light trench mortars, Whippet tanks, etc.”29

He requested and was granted government permission for: “(a) The provision of the necessary staff for command, (b) The formation of a Secret Service, (c) The organisation, training and equipping of the forces as they at present exist, and of an additional 20,000 Class ‘C’ Special Constables.”30

An army by another name

Solly-Flood inherited the contradiction in Wilson’s role – that of being a Military Adviser in the absence of an army. His solution to the conundrum was to create an army.

Within two weeks of being appointed, he wrote to General Nevil Macready, who was still the British Army’s General Officer Commanding-in-Chief in Ireland but was by then pre-occupied with the evacuation of British troops from the Free State:

“With our hands tied as they are at present by the Treaty it is difficult to raise and organise the number of men that would be necessary to meet probabilities…Could you give me any line to ride in the matter of:

(1) An Air Service

(2) Some tanks, Whippets for choice

(3) Light Stokes mortars

(4) Personal equipment in large numbers, and

(5) A few steel hats.”31

He also wrote to Major General Hugh Trenchard, the chief of the Royal Air Force:

“Neither ourselves nor the soldiers have a single aeroplane in the place i.e. in the north…If you cannot send a squadron, you might find an excuse to send a flight, for training or other purposes. I want them at once for purposes of communication, later I might ask to be allowed to use them offensively, of which bombing under carefully arranged plans might form a part.”32

Which side of the border would be subject to these bombing missions was not made explicit.

Finally, he wrote to Major General Gerald Ellison, Quartermaster General of the British Army, enclosing a three-page typed list of his requirements in terms of equipment, one that went into microscopic detail – it included everything from 10,000 rifles to 100 bugles down to ten each of three different types of chisel.33

Feeling pleased with his efforts thus far, Solly-Flood sent copies of this correspondence to Spender, stating that it was just the start of what he had in mind: “I do not want them to think that if they meet this demand they have finished with us by any means. As they have no Whippet tanks, I am prepared to take some Mark V as long as they are serviceable…48 tanks would be a great help.”34

Solly-Flood wanted 48 Whippet tanks (L) for the Specials but was prepared to settle for Mark Vs instead (R)

Naturally, Solly-Flood’s requests were passed around the bureaucracy of government in London, leading the British Assistant Cabinet Secretary, Tom Jones, to observe in a memo: “[they have] assumed the military functions specifically reserved to the British government simply by calling their forces police.”35

As Colonial Secretary and chair of a cabinet sub-committee on Ireland, Winston Churchill was the government minister with most responsibility for Irish affairs. He reacted with barely controlled fury, writing to tell Craig:

“I must emphasise the fact that the defence of Northern Ireland is an inalienable obligation of the Imperial Government and that you are entitled to look to the British Army in everything that is not concerned with local order. It is not the business of the Ulster police to have an air force.”36

Churchill concluded with a blunt reminder of the appropriate channels for communication, putting Solly-Flood – and by extension, Craig himself – back in their boxes:

“Lastly Solly Flood’s correspondence should not be direct with the War Office and Air Ministry. He should communicate with your government under whom he is serving and your government should communicate with me as the chairman of the cabinet committee dealing with Irish matters. I will then consult both with Cameron and Macready…and will communicate with you accordingly.”37

When shown Churchill’s broadside, a chastened and very crestfallen Solly-Flood admitted to Spender that “[it] has brought me out of Utopia with a sorry bump.”38

Instead, he now proposed dealing with the IRA’s small, fast-moving flying columns by the novel tactic, previously untried in guerilla warfare, of firing artillery at them:

“Since aeroplanes are ruled out of court, the wireless becomes all the more important…I do not mind so much about the Whippet tanks, although they would have been a great asset. If I can get a few Stokes mortars I will do the best I can with them, but I should also like to be able to count upon a few field guns & howitzers for training purposes to replace the tanks which have been vetoed. Such guns would be of great value in rounding up raiding parties…”39

On 11 May, Solly-Flood submitted a revised forecast of the numbers of Specials that would be required:

- 8,290 A Specials, an increase of 3,300 on his previous estimate

- 25,000 B Specials, an increase of 5,000

- 7,000 C Specials

- 20,000 C1 Specials

There would be two Brigades of C1 Specials for Belfast and another for country areas; he also wanted a unit of Specials cavalry, consisting of a “Headquarters & three squadrons mounted Constabulary…modelled on the lines of the North Irish Horse.” Solly-Flood even envisaged that he might also benefit personally by securing a promotion – at the top of this planned organisation would be a Lieutenant General, presumably himself, served by “Three officers not above rank of Major General [his then rank.]”40

C Specials in Chichester St, Belfast

Comprehensive lists of the quantities of uniforms, rifles, Lewis guns, revolvers and 3” mortars needed to clothe and arm this force were attached; to move all these men around, he would need 139 Crossley tenders, 62 Lancia armoured cars and 129 ordinary cars – in addition to the 483 such vehicles already available.41

All of this had to be paid for.

The British Treasury had originally allocated £850,000 to cover the costs of the USC in the financial year April 1922-March 1923. Before even Wilson had arrived, let alone Solly-Flood, Wickham had requisitioned extra vehicles and armaments that would more than double the costs to £1,829,000.42

The Ministry of Home Affairs was asked to provide an estimate of the cost of Solly-Flood’s proposals but they hesitated to stand over their own figures: “In these circumstances it is very difficult to give an estimate which will approach to accuracy.” Nevertheless, they took a deep breath, allocated amounts against each component of Solly-Flood’s proposed organisation and came up with a total of £3,604,167. Even then, they only provided for the costs – in terms of part-time pay – of mobilising 5,000 B and C Specials, not the whole 52,000 that Solly-Flood wanted on the books. This £3.6m was to be in addition to the estimate already before Parliament and a separate estimate of £1.5m a year for running the new Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), thus making a grand total of £6.9m.43

On 15 May, Solly-Flood’s plans were debated at a cabinet sub-committee set up to deal with the USC, consisting of Craig, Lord Londonderry and the Parliamentary Secretaries to the Ministers of Home Affairs and Finance, as well as Solly-Flood, Wickham and Spender.

Still smarting from Churchill’s reprimand, Craig reminded them:

“…that the force must be kept on a purely police basis as the Government of Ireland Act prohibits the northern government from legislating for the upkeep of military forces. In making plans the possibility of invasion was not to be considered, as in this event the imperial forces would be called in. The organisation should be such as would adequately deal with internal trouble.”44

With that preamble duly placed on the record, all of Solly-Flood’s proposals in relation to the structure and manpower required were approved. At a subsequent meeting of the sub-committee on 17 May, Craig said that “he would forward them [the financial estimates] to the Colonial Office and ask that the cost should be met by the Imperial Government.”45

Reactions to the IRA’s “northern offensive” and the Civil War

Even before the launch of the its “northern offensive,” Solly-Flood was particularly concerned about a build-up of IRA forces along the border – in a memo on 18 May, he referenced various camps in Monaghan of “IRA (De Valera)…republicans who took their orders from the Four Courts in Dublin.” He highlighted the discovery of arms dumps in Newry and south Armagh, the capture of IRA 4th Northern Division documents relating to the offensive and quoted a statement to the press by the IRA’s Seán Lehane referring to operations that his forces had undertaken in the north as evidence of “the work of the De Valeraite section.”46

However, Solly-Flood’s intelligence reports were not entirely flawless – in a startling premonition of future developments in Germany, he described Lehane, a Cork IRA officer, as “Formerly Commandant of the 3rd Dublin ‘Storm Troops.’”47

In the wake of the IRA’s attack on Musgrave St Barracks on the night of 17/18 May, the Northern Ireland Government met on 20 May and adopted a set of proposals put forward by Solly-Flood:

“To deal with the new situation created General Solly-Flood recommended that the following illegal organisations should be immediately proscribed, viz:-

The IRA

The IRB

The Cumann-na-m’Ban, and

The Fianna-na-L’Eireann [sic].

Also that certain suspected persons should at once be arrested and detained under the Civil Authorities Act.”48

The timing is significant, as it has generally been assumed – including by me – that the introduction of internment was in part triggered by the IRA’s killing of Unionist MP William Twadell on 22 May; in fact, the decision to proceed with internment was made two days before Twadell was shot.

Internees being taken through Belfast

However, Solly-Flood wanted to go even further, but the cabinet baulked at his next suggestion: “General Solly-Flood also stated that he considered that a special tribunal should be set up with power to inflict the death penalty in certain cases. It was, however, decided to postpone this matter for further consideration.”49

Undeterred, he returned to the same theme at another cabinet meeting held just three days later:

“General Solly-Flood again brought up the question of the death sentence being inflicted in all cases of persons found carrying firearms and asked that a special court be set up to deal with such cases immediately and that no right of appeal be allowed against the capital sentence. It was decided, however, to postpone this matter for further consideration.”50

A statement from Major General A.J. Cameron, the British Army’s General Officer Commanding (GOC), Ulster District, was read to the meeting – his priorities were “(a) Resisting invasion from the Free State, (b) Assisting the police in Belfast, (c) Providing detachments to support the police outside Belfast.”51

Craig wanted to give both Cameron and Solly-Flood complete carte blanche to deal with the latest crisis, without them necessarily feeling that they had to stay within the boundaries of the law:

“The Prime Minister pointed out that if a sudden emergency arose in consequence of the present trouble it may be necessary for the GOC or General Solly-Food to take some drastic action that would not be strictly covered from a legal point of view…the cabinet should give a written undertaking that the Government of Northern Ireland would be prepared to stand over any such action taken. This was unanimously approved.”52

In the aftermath of this cabinet meeting, Solly-Flood warned all senior police and Specials officers that doomsday was about to arrive:

“The state of unrest throughout Ireland due to the activities of the IRA and to the Bolshevic [sic] aims of southern agitators is an obvious indication that it can only be a question of time before open hostilities between the north and south break out.”53

He said that what he called “the preparatory phase” had passed and that they had now arrived at “the precautionary phase”, though not yet at “war – or the outbreak of hostilities;” that final stage related to actual invasion from the south.

Pending that, he instructed that “All disaffected areas in cities and counties may be proclaimed forthwith,” meaning there would be no movement of people or vehicles in or out of these areas apart from British military, RIC and Specials, trains and “provedly loyal persons.” He also insisted that all trains entering or leaving Northern Ireland, and even those simply passing through disaffected areas, were to be searched; armoured carriages were also to be attached to the latter.54

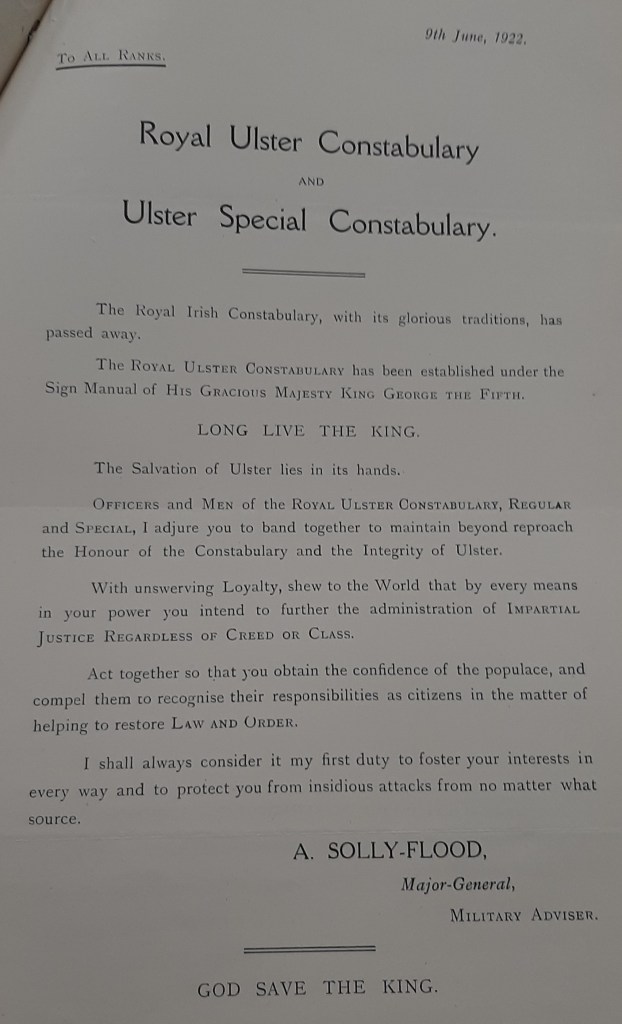

In early June, shortly after the formal disbandment of the RIC and formation of the new RUC, he issued what he no doubt considered to be a rousing and inspirational proclamation to it and the Specials. Wickham, as the first Inspector General of the RUC, might justifiably have felt that such a proclamation should have come from him, but his reaction to Solly-Flood stealing his thunder is not recorded:

Solly-Flood’s proclamation to the RUC and Specials; © PRONI CAB/6/28C, reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI

“The Royal Irish Constabulary, with its glorious traditions, has passed away. The Royal Ulster Constabulary has been established under the Sign Manual of His Gracious Majesty King George the Fifth. LONG LIVE THE KING.

The salvation of Ulster lies in its hands.

Officers and men of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, regular and Special, I adjure you to band together to maintain beyond reproach the honour of the Constabulary and the integrity of Ulster.With unswerving loyalty, shew to the world that by every means in your power you intend to further the administration of impartial justice regardless of creed or class.

Act together so that you can obtain the confidence of the populace and compel them to recognise their responsibilities as citizens in the matter of helping to restore law and order.”55

British troops marching to capture Belleek; Solly-Flood wanted to occupy other areas south of the border

In mid-June, after the Battle of Belleek-Pettigo, Solly-Flood revived the idea of re-conquering areas south of border; he said that in the event of the IRA firing across the border into the north:

“I would recommend that authority be given for the royal forces (police or military, or both) to take and hold such localities on the far side of the boundary as will ensure the protection of the people of Ulster. I lay stress on the word ‘hold’ for two reasons. Firstly, it is not sound from a military point of view to cross the border on a punitive expedition and to retire on completion, and, secondly, it will not prove effective for the reason that when the troops or police retire, the IRA will advance and the firing will break out anew.”56

A civil servant drily noted that this suggestion “raises a very large question of policy” – namely, was the northern government to invade the Free State?57

Later that month, he proposed a new policy to restore law and order and listed the detailed actions necessary to carry out that policy.

The policy was to involve hunting down and arresting all the members of the already-banned republican organisations; in the event of IRA attacks, “attack immediately selected Sinn Fein quarters in the city, or district in the counties. Arrest all males of fighting age and search thoroughly for arms, explosives, seditious documents, etc.” In the event of attacks by loyalists on Catholics, the offenders should be arrested and any arms and explosives confiscated.58

The detailed steps to achieve this policy represented his most punitive, draconian proposals to date – they included:

- Closing the border

- Special courts “to have special powers of life and death from which there will be no appeal and sentence to be executed within 48 hours.”

- Arson or illegal possession of arms to be punishable by death

- The creation of rural and urban ghettos into which anyone disloyal – meaning nationalists – would be forced to move and remain: “Allocate certain areas in the counties or quarters in the cities in which all individuals other than those of proved loyalty must reside and must not be allowed to quit. This entails…emptying certain other areas of individuals who are not undisputed loyalists.”

- Provision of a second internment ship to supplement the SS Argenta

- “Formation of an efficient CID.”59

However, Solly-Flood no longer had the eagerly receptive audience that he had enjoyed before the summer. In fact, he complained that this and three previous policy proposals he had made during June had received no response at all.60

Undaunted, he came up with a new idea, recommending that the Northern Ireland Parliament pass legislation putting the C1 Specials on the same footing as the Territorial Army in Britain, but allowing for compulsory annual training and mobilisation, with the northern government responsible for mobilising the force. He also wanted conscription: “To discipline a nation under arms it is aimed at getting the whole physically fit manhood – of suitable character – into the C1 force.”61

An IRA arson attack in Talbot St; Solly-Flood wanted to introduce the death penalty for arson

A curt response from a civil service Assistant Secretary came almost two weeks later: “the Parliament of Northern Ireland is prohibited from establishing the force suggested in your minute. Legislation by the Imperial Parliament would be required.”62

The outbreak of the Civil War south of the border was a new source of anxiety for Solly-Flood – jealous that Collins was being given new toys which had been denied to him, his fears of invasion from the south were further amplified. In a memo to Craig, he returned to the idea of conscription into the Specials:

“It is true that the Provisional Government is ostensibly endeavouring to restore law and order by drastic means. For this object, the Provisional Government is obtaining from some source or another, both artillery and aeroplanes and further they have passed, or contemplate passing a law which amounts to universal service.

…I should be lacking in duty to the northern government were I not to point out that the correct answer to the Provisional Government’s proclamation of universal service would be some similar move on their part.

…the most economical and efficient form that this could take would be that of expanding the C1 (Special Constabulary) form throughout the Six Counties into a Territorial Special Constabulary. Such a measure would be vastly facilitated by a move on behalf of the northern government, at this critical juncture, to compel all males within certain limits of age and physical capabilities to serve in this branch of the force.”63

A recruitment office in Dublin; in response to the expansion of the Free State Army, Solly-Flood advocated the conscription of “all males” to the Specials (© National Library of Ireland)

It is typical of his impulsive decision-making that Solly-Flood mentioned “all males” without stopping to consider that a considerable portion of those males were already extremely hostile to the Specials on the basis of political outlook and personal experience and so would probably not be particularly enthusiastic or loyal recruits.

On the other hand, Craig himself regarded the outbreak of the Civil War as an elaborate hoax concocted by the pro- and anti-Treaty elements in the south to undermine the vigilance of both the Unionist and British governments; on the very day that the shelling of the Four Courts began, he wrote to Churchill:

“…I need scarcely warn you against being humbugged by the sham ‘battle’ at present being waged by Collins against Rory O’Connor; no doubt the former will palm it off as an earnest of his desire to carry out the Treaty; it is very likely that a secret arrangement has been come to between the two! Be on your guard.”64

Parity of disdain

By early July, Solly-Flood seemed bent on antagonising both communities in Belfast.

After a platoon of Specials conducting searches in Ardoyne were abused by local residents, Colonel G.H.N. Jackson, his Chief of General Staff, wrote to Wickham:

“Such demonstrations border on contempt for the Constabulary, a state of affairs which is highly unsatisfactory. It is essential, especially in disaffected areas, that the population should have a wholesome respect for the Constabulary – both regular and special. In these disaffected areas the only method of inducing this respect is by instilling fear. On occasions when open – even if not active – hostility is shown, it must be suppressed immediately by a judicious baton charge. Please arrange that all raiding platoons should carry a proportion of batons for this purpose.”65

Asked for his views, City Commissioner Gelston wearily replied that Specials being jeered was simply par for the course: “…unaware of any hostile demonstration beyond what comes from women and children barking [shouting]. No active hostility occurs. This barking is customary where police have to take action and in my opinion it is better to ignore it.” He went on to point out that attempting such a baton charge would be an exercise in futility as the scallywags would simply start playing hide-and-seek:

“Baton charges against women and children would be a mistake…barking and jeering by children or even women could hardly be construed as ‘obstruction.’ The probable result of a baton charge would be the people would run into their homes and when the police ran by they could come out again behind them and cheer them on.”66

However, Solly-Flood’s attitude to the Orange marches on the Twelfth definitely confounds expectations.

In the run-up to the event, General Cameron had voiced concerns following disturbances at an earlier march:

“…a procession had recently taken place sanctioned by the police in a part of the Newtownards Road where assemblies are forbidden by Military Proclamation…The procession in this instance was followed by an irresponsible crowd who fired shots down the Roman Catholic streets…though the Orange processions themselves are quite orderly they are followed frequently by a disorderly crowd.”67

Orange parade on the Twelfth, 1922; Solly-Flood wanted to re-route the parades away from any areas where they would be unwelcome

In response, Solly-Flood told Colonel Jackson that he wanted the parades to be limited in terms of participants and that they were not to parade in areas where they might not be welcomed by local residents:

“I have instructed IG [RUC Inspector General] that while it is inadvisable to place any embargo on these celebrations as regards the bands and lodges themselves, followers are not to be allowed…Further pressure should be brought to bear thro’ heads of the Orange organisation to meet my wishes in regard to processions avoiding localities where trouble is likely to arise.”68

Solly-Flood also emphasised the need to re-route the Orange marches in a memo to Craig’s secretary, but in the event, the Twelfth parades went ahead exactly as the Orange Order had planned.69

In mid-July, Solly-Flood intervened on the side of Catholic refugees from east Belfast who were squatting in the Ekenhead Mission Hall in May St – the trustees of the hall wanted to evict them and regain possession of the hall, but Solly-Flood pointed out that:

“Their homes are now occupied by Protestants who are, presumably, just as much in illegal possession as they are in illegal possession of Mission Hall…In plain words, are these Roman Catholic refugees from fear of Protestant aggression not entitled to the same consideration as the Protestant refugees from fear of the IRA?”70

Solly-Flood’s staff had evidently decided to feed his penchant for hare-brained schemes, so while his attention was turned to the Orange Order, they had the bright idea of provoking the Catholic Church.

The CID suggested installing a radio mast on the spire of St Malachy’s church in the Market, in order to maintain communications with Danesfort House in the event of an IRA attack on it. But Gelston was aghast: “It would cause intense and bitter resentment; be regarded as a desecration, and would lead to representation being made through [sic – to] the northern government through the English government.” The scheme did not go ahead.71

St Malachy’s: the RUC City Commissioner felt the CID’s plan to instal a radio mast on its spire would be viewed as “a desecration”

Solly-Flood himself requested permission to search monasteries, churches and convents for arms. Dawson Bates was prepared to agree, although he stipulated that convent dormitories were only to be entered by women searchers and even then only after the nuns had been removed, but he was over-ruled: “The Prime Minister points out that such searches would turn public opinion against the government.” No such searches were to go ahead without Craig’s express permission.72

But wider events were catching up with Solly-Flood, who was yet to unveil a proposal so startling that it would dwarf anything he had previously recommended. Both of these subjects will be discussed in Part 2 of this post.

References

1 Keith Jeffrey, ‘Wilson, Sir Henry Hughes,’ Dictionary of Irish Biography https://www.dib.ie/biography/wilson-sir-henry-hughes-a9074

2 Ibid.

3 Freeman’s Journal, 22 March 1922.

4 Ronan McGreevy, Great Hatred: The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP (London, Faber, 2022), p128.

5 Henry Wilson to James Craig, 31 May 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

6 McGreevy, Great Hatred, p268.

7 Ibid, p210-212.

8 Ibid, p291.

9 Ibid, p291-292.

10 Minutes of Cabinet meeting ,13 March 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/35.

11 Notes of a Conference held at the Ministry of Home Affairs on 17th March 1922, PRONI, Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 27 March 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/37.

15 Military Adviser (Field Marshall Henry Wilson) to Prime Minister, 17 March 1922, PRONI, Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Patrick Long, ‘Flood, Arthur Solly-,‘ Dictionary of Irish Biography https://www.dib.ie/biography/flood-arthur-solly-a3292

19 Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 24 March 1922 & Cabinet Secretary to Military Adviser, 28 March 1922, PRONI, Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89; Edward Burke email to author, 21 June 2024.

20 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 1 April 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/38.

21 Cabinet Secretary to Ministry of Home Affairs, 20 April 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence April 1922 – June 1922, CAB/6/28A.

22 S.M. Kennedy to Wilfrid Spender, 10 April 1922, ibid; Minister of Education to Prime Minister, 14 August 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

23 Bryan A. Follis, A State Under Siege: The Establishment of Northern Ireland 1920-1925, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995), p92; Military Adviser (Major General Arthur Solly-Flood) to Quartermaster General to the Forces,13 April 1922, PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41.

24 Charles W. Magill (ed), From Dublin Castle to Stormont: The Memoirs of Andrew Philip Magill 1913-1925 (Cork, Cork University Press, 2003), p70. Not for the first time, I am deeply grateful to Paddy Mulroe for alerting me to the existence of this reference.

25 Ministry of Finance to Military Adviser, 8 June 1922, PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41; Military Adviser to Ministry of Finance, 26 June 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence June 1922, CAB/6/28C; https://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2014/05/cabin-hill.html.

26 Military Adviser’s Preliminary Report, n.d., PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Military Adviser to General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Ireland, 7 April 1922, ibid.

32 Military Adviser to Chief of the Air Staff, 15 April 1922, ibid.

33 Military Adviser to Quartermaster General to the Forces,13 April 1922, ibid.

34 Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 19 April 1922, ibid.

35 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983) p97-98.

36 Colonial Secretary to Prime Minister, Northern Ireland, 19 April, PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41.

37 Ibid.

38 Military Adviser to Cabinet Secretary, 3 May 1922, ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Estimates for establishment, 11 May, ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Farrell, Arming the Protestants, p87; Follis, A State Under Siege, p92.

43 Memorandum, unsigned, n.d., PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41.

44 Minutes of Cabinet sub-committee meeting, 15 May 1922, ibid.

45 Minutes of Cabinet sub-committee meeting, 17 May 1922, ibid.

46 Military Adviser, Restoration of law and order, 18 May 1922, ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 20 May 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/43.

49 Ibid.

50 Minutes of Cabinet meeting, 23 May 1922, PRONI, CAB/4/44.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Military Adviser to Divisional Commissioner, City Commissioner, County Inspectors, County Commandants, 24 May 1922, PRONI, Military Adviser’s proposals, CAB/6/41.

54 Ibid.

55 Proclamation, 9 June 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence June 1922, CAB/6/28C.

56 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 15 June 1922, PRONI, Suggestion by Military Adviser that firing from Irish Free State into Ulster could be prevented by British Military occupying Free State, HA/32/1/186.

57 File note by A.P.M. (Andrew Philip Magill?), 16 June 1922, ibid.

58 Appendix A, Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister and Ministry of Home Affairs, 22 June 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence June 1922, CAB/6/28C.

59 Appendix B, ibid.

60 Military Adviser to Ministry of Home Affairs, 24 July 1922, PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

61 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 5 July 1922, ibid.

62 R.R.P. (full name not recorded) to Military Adviser, 17 July 1922, ibid.

63 Military Adviser to Prime Minister, 7 July 1922, Military Archives (MA), Historical Section Collection (HSC), List of principal reprisals, HS/A/0988/01.

64 Prime Minister to Colonial Secretary, 28 June 1922, PRONI, Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

65 Chief of General Staff to Inspector General, 7 July 1922, MA, Bureau of Military Contemporary Documents Collection (BMHCD), Colonel Seumas Woods Collection, Obstruction of police in execution of their duty, BMH/CD/310/02.

66 City Commissioner to Inspector General, 15 July 1922, ibid.

67 GOC Ulster District to Prime Minister, 4 July 1922, MA, BMHCD, Colonel Seumas Woods Collection, 12th July Orange Order celebrations day, BMH/CD/310/13.

68 Military Advisor to Chief of General Staff, 5 July 1922, ibid.

69 Military Adviser to Secretary to Prime Minister, 5 July 1922, ibid.

70 Military Adviser to Ministry of Home Affairs, n.d., MA, HSC, Miscellaneous, HS/A/0988/20.

71 Assistant Director, CID to Director, 7 July 1922; City Commissioner to Inspector General, 16 July 1922, MA, HSC, Spire of St Malachi’s, HS/A/0988/03.

72 Ministry of Home Affairs to Military Adviser, 22 July 1922 (two separate memos with same date), PRONI, Military and police, general correspondence July 1922 – September 1922, CAB/6/29.

Leave a comment