Estimated reading time: 25 minutes

Introduction

The attack on the McMahon family, in which Owen McMahon, four of his sons and his barman and lodger, Edward McKinney, were killed took place on the night of 23/24 March 1922. Just over a week later, the police mounted another attack leading to multiple fatalities in and around Arnon St in Carrick Hill.

While there is a well-known photo of Owen McMahon, three of his sons and McKinney lying dead, there are also photos of the victims of what came to be known as the “Arnon St killings.” The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) has kindly granted me permission to reproduce those photos in this post.

The McMahon photos

The events of the night of 23/24 March in Kinnaird Terrace off the Antrim Road are well-known. Owen, Patrick, Frank and Thomas McMahon and Edward McKinney were all killed; two of Owen McMahon’s other sons, Bernard and John, were badly wounded.1

The dead men in the morgue of the Mater Hospital (Freeman’s Journal, 28 March 1922)

The four dead McMahons were buried in Milltown Cemetery on Sunday 26 March; McKinney was buried in his native Buncrana in Donegal on the same day. Prior to the funerals, a photo of the five fatalities was taken in the morgue of the Mater Hospital – this was published by the Freeman’s Journal in Dublin on 28 March, accompanied by photos of Bernard and John McMahon taken in their beds in the same hospital; each of the pictures was captioned “Freeman Exclusive Photo”.

Bernard (L) and John (R) McMahon, photographed in hospital after the attack (Freeman’s Journal, 28 March 1922)

“Peace is today declared”

Public opinion in Britain was particularly outraged at the McMahon family murders and in the ensuing outcry, the Secretary for the Colonies, Winston Churchill, felt compelled to convene a tripartite meeting in London a few days later with Michael Collins, chairman of the Provisional Government, and James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

On 30 March, the second “Craig–Collins Pact” was signed. Churchill insisted that its opening clause should announce: “Peace is today declared.” In article 3, the agreement specified important changes in policing:

“The police in Belfast to be organised in general in accordance with the following conditions:

- Special police in mixed districts to be composed half of Catholics and half of Protestants, special agreements to be made where Catholics or Protestants are living in other districts. All Specials not required for this force to be withdrawn to their homes and their arms handed in.

- An Advisory Committee, composed of Catholics to be set up to assist in the selection of Catholic recruits for the Special Police.

- All police on duty, except the usual secret service, to be in uniform and officially numbered.

- All arms and ammunition issued to police to be deposited in barracks in charge of a military or other competent officer when the policeman is not on duty, and an official record to be kept of all arms issued, and of all ammunition issued and used.

- Any search for arms to be carried out by police forces composed half of Catholics and half of Protestants, the military rendering any necessary assistance.”2

Unionism looked askance at the pact: “Craig had a stormy reception on his homecoming and there was soon considerable opposition to the pact expressed in the northern parliament.”3

An even more hostile response by loyalists serving in the police was exemplified by a former UVF commander:

“The old Tyrone Specials leader General Ricardo put his finger on the police clause’s weakness when he commented: ‘It will never be possible to recover the arms from the “B” Specials…To allow the Specials to become mixed was to destroy the security, in loyalist minds, of their state.’”4

Within days of the pact’s signing, it had already largely become a dead letter.

The Arnon St killings

On the evening of 1 April 1922, Constable George Turner was shot dead on the Old Lodge Road in Carrick Hill.

A Special Constable who had been accompanying Turner told the inquest that the fatal shot came from a derelict building at the corner of Stanhope St.5

But according to historian Andrew Boyd, “At an official enquiry later, British soldiers who had been on duty on Old Lodge Road said the shot which killed Turner could not have been fired from any of the Catholic streets.”6

Constable George Turner

The Provisional Government said it was the soldiers themselves who had shot Turner.

This assertion was based on two sources: on 3 April, Dr Henry McNabb, Medical Officer of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, phoned the Provisional Government’s press office, asking that a message be urgently relayed to Collins: “A military picket, located in Stanhope Street, a Catholic area, fired a volley into the Orange area, in reply to shooting from that area into Stanhope Street and Arnon Street. Presumably the action (firing) of the military was the cause of Constable Turner’s death.”7

On the same day, Daniel Girwin, who lived at 11 Stanhope St, made a statutory declaration:

“I was sitting at the fire reading at about ten minutes to eleven o’clock when a shot was fired up Stanhope Street. I went to the door and saw a policeman at the corner of Stanhope Street and Old Lodge Road fire up Stanhope Street in the direction of Park Street. The military replied killing that policeman.”8

But although the circumstances of Turner’s killing were disputed, there was less debate about what ensued.

There was prelude which is important, as it identifies one of the organisers of what happened later. Constable E. O’Donnell was based in Glenravel St Barracks; a nationalist, he was in regular contact with the Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s local battalion. According to an intelligence report sent to Dublin, he was on duty that night:

“Just before the horrible occurrences took place, Constable Gordon, Brown Square, approached O’Donnell and asked him if he was going to take part. O’Donnell told him he certainly was not and would prevent, as far as he could, murder. Gordon produced a revolver and threatened O’Donnell, ordering him out of the way under pain of being shot.”9

Edward Burke has identified Constable Henry Gordon as originally being from Cavan; he was named in one report as being among the police “murder gang” responsible for the killings of Ned Trodden, John McFadden and Seán Gaynor in September 1920 and in a separate report as being one of those who killed three Catholic civilians, William Kerr, Alexander McBride and Malachy Halfpenny in June 1921.10

Gordon was also named as one of two policemen who had gone to a workmen’s hut at Carlisle Circus and stolen the sledgehammer used to break in the front door of the McMahon family home.11

Later on the night of 1 April, a mixed party of regular police and Specials left Brown Square Barracks in Lancia armoured cars.

Although no direct eye-witness testimony placed him at the scene, second-hand accounts said the raiders were led by the notorious District Inspector John Nixon, who was the officer in charge of that barracks: “Fr Laverty, a local Catholic priest who was in touch with the [nationalist] police witnesses, told S.G. Tallents, a British civil servant enquiring into the working of the pact, that ‘police of Brown Square barracks were the offenders. A DI Nixon at head of gang [of]…old RIC men.’”12

Dismounting from the armoured cars, the police first made their way up Stanhope St, shouting “Cut the guts out of them for the murder of Turner!”13

Like many other areas in Belfast, the walls of the back yards in Stanhope St and Arnon St had been tunnelled through to allow residents to move about safely without being exposed to snipers’ gunfire. The police broke into number 15, the home of William Kitson, who later stated:

“I was in my bed in 15, Stanhope Street at 11.20 on Saturday night when I was awakened by the noise of men hammering…There was in my house John McCrory the deceased and his wife (who had apartments there), as well as my wife and three children…When I came down John McCrory was making his way through a hole in the yard of the next house. John then said: ‘We are jammed, it is hopeless.’ John McCrory came back into my yard and I said ‘For God’s sake escape some way.’ I threw myself down with two of my children alongside of the wall in my yard and threw coverings over myself and the children, who were in their night clothes. John McCrory then made his way into the yard of 13 Stanhope Street. While there, four or five men, one of whom I saw with arms, rushed into my yard and through the hole into No. 13. The armed man shouted: ‘Hands up you bastard.’ John McCrory then said ‘All right, son. I never done hurt nor harm to nobody.’ The armed man then said: ‘Not so much of your sonning, get them up, you bastard’ and fired three or four shots…The armed man was Constable Gordon of Brown Square Barracks.”14

Park St was a side street off Stanhope St. At number 26, Bernard McKenna, a father of seven, was upstairs getting undressed for bed. A neighbour, Catherine Hatton, had been visiting his wife:

“I was in Mrs McKenna’s house in Park Street between 15 and 10 minutes past 11…A knock came to the back door. Mrs McKenna opened it. In came two men in plain clothes and two in uniform. Latter had rifles, the former revolvers. I know one of them: Constable Gordon. He knows me but I hid my face with a baby in my arms. He asked Mrs McKenna who was in the house, and she answered no one but herself and her husband and children. The men went upstairs Gordon leading. They ordered Mr McKenna into the front room to be searched. He did so and immediately three shots were fired and the four men then came into the kitchen and said if we raised an alarm they would blow our brains out.”15

The police moved on to Arnon St, which ran parallel to Stanhope St. William Spallen, who lived at number 16, had attended his wife’s funeral earlier that day; he was in bed with his grandson, Gerald Tumelty, who later said:

“I was wakened by the firing…I heard footsteps on the stairs and two men came into the room. One of the men lit a match and I then saw that he was in plain clothes and the other man was in the uniform of a policeman. The man in plain clothes asked my grandfather his name and he answered ‘William Spallen.’ He then raised his revolver and fired three shots at my grandfather. This man snatched money which was in my grandfather’s right hand…the money which he had for funeral expenses…I was 12 years old on the 11th Feb. 1922…I know that if I swear a lie I will go to Hell…I could recognise the man in plain clothes as I had seen him before on the Old Lodge Road.”16

The Walsh family lived next door at number 18. Joseph Walsh, aged 26, was an ex-serviceman, having been in the Connaught Rangers during the Great War. His wife Elizabeth stated:

“I was sleeping in the room downstairs on the night of Saturday, 1st April, 1922. My husband was in the back room upstairs with two of the children. This was about 11 o’clock. After this my door was broken in. I ran upstairs and told my husband. I had the infant of two weeks old in my arms. I went into the front room. Some men came upstairs and came into the front room…One of the men flashed the light under the bed in the front room and went out again. After that a number of shots were fired and my son Michael shouted ‘Oh my daddy is shot!’”17

The Walshes suffered the most frenzied attack of that night. Joseph Walsh was bludgeoned to death with the sledgehammer used to break down the front door; a priest who visited the family later that night said, “The skull was open and empty; while the whole mass of the brains was on the bolster almost a foot away.” For good measure, the raiders shot Walsh and the two children lying beside him, Michael, aged 7, and Bridget, aged less than 2.18

Joseph Walsh (photo courtesy of 6th Connaught Rangers Research Group)

George Murray was a Protestant married to a Catholic; they lived two doors away from the Walshes at number 12. A fortnight before the attack, “he received a notice which intimated he would have to look out as he was considered a spy for the Catholics.”19

By a sheer fluke, he lived to describe what happened:

“About 11 o’clock p.m. I heard the shooting up the street and I went upstairs. I heard the doors being banged with hammers. They then came to my house and broke in the windows and doors. The men who did this were dressed in the uniform of policemen. When I came downstairs I had a child in my arms, and was met in the hall by three policemen, one of whom had a revolver and the other two guns…He took a look into the parlour and then said: ‘It is all right close the door and go to bed.’

…a loud knocking took place at the door. I then went and opened it. There were seven armed men [who] then entered, five in police clothes and two in plain clothes. They had a cage car outside the house. I told them the police had been at my house and one of the men in civilian clothes said ‘Come into the kitchen till I see who you are’…Then another policeman came forward and put a gun to my head…He then said: ‘Get the child out of your arms.’ Another of the same party then said: ’I will do it.’ I then went to leave the child down when a shot was fired going over my head and striking the wall of the fire place leaving a hole as large as my hand. They all then left.”20

A few days later, an anonymous correspondent wrote from Belfast to Collins, alleging that there had also been sexual violence that night: “I want to mention one thing specially it is after one of the men being murdered. The men that did it went so far as to try and rape the mans [sic] wife. But thank God in that they failed.”21

There is no other evidence to prove or disprove this claim. William Spallen’s wife had been buried earlier that day. Elizabeth Walsh did not mention such an attack in her deposition. Nor did William Kitson or Catherine Hatton, who were in the same houses as the wives of John McCrory and Bernard McKenna respectively, mention it in theirs. However it should be borne in mind that sexual violence was generally under-reported at the time, so we simply cannot tell whether the allegation had any substance.

While four men were killed instantly, that was not the end of the deaths: 7-year-old Michael Walsh died from his wounds the next day, 2 April. But even that was not the last suffering inflicted on the wider Walsh family – on the morning of 2 April, Michael’s cousin Robert, aged just 8 months, who lived with his parents further down Arnon St at number 35, was in the arms of a neighbour; a sniper fired at them, the bullet passing through her arm and killing the baby.22

In a grimly symmetrical twist, Bernard McMahon also succumbed to his wounds on 2 April, thus becoming the sixth fatality of the earlier attack.

The aftermath

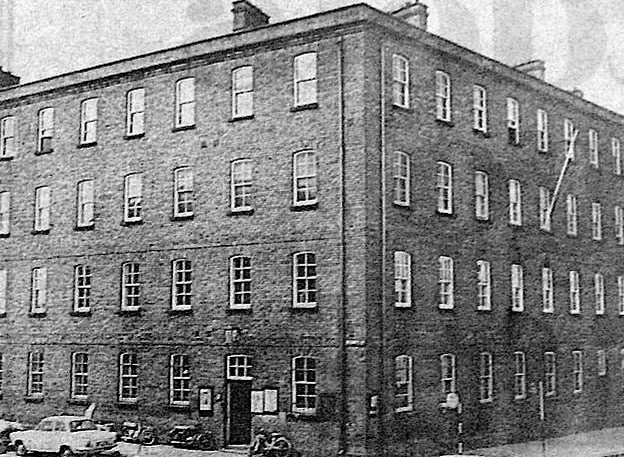

Brown Square Barracks

On the morning of 5 April, a notice was posted in Brown Square Barracks, notifying all police stationed there to attend an identity parade at 4pm. Constable Gordon reacted angrily: “’Look at that, it’s a nice thing that we’ll have to parade before the whores of Stanhope Street. There’s one certainty, I won’t be there.’” The identity parade did not go ahead.23

That afternoon, unaware that it had been called off, Elizabeth Walsh called to the barracks to attend the identity parade as an eyewitness to the events of the previous Saturday:

“When it was not held she left and when coming out of the barracks a group of policemen amongst whom was Const. Gordon were standing at the door. She pointed to Gordon and said ‘there’s the man who murdered my husband.’ The group immediately threw her out of the barracks and it is alleged kicked her out.”24

Collins demanded a special enquiry be held into both sets of killings, those of the McMahons and those in Carrick Hill, but Craig refused, insisting that a normal police investigation would suffice: “In view of the pleasing fact that peace has reigned for 24 hours I consider it would be injudicious to go back…on the cases of Walsh, Spallen, McCrory and McKenna…The authorities are making every endeavour to bring the criminals to justice.”25

In the event, no enquiry was held and it was left to the Belfast Coroner’s Court to deliver the usual anodyne verdict at the inquest – that those killed in Carrick Hill had been the victims of “murder by an illegal assembly,” without the members of that assembly being identified.26

The Arnon St photos

On 28 May, the former Military Adviser to the Government of Northern Ireland, Field Marshall Henry Wilson, wrote to Craig; he enclosed a copy of the London edition of the Irish Bulletin published four days earlier.27

The Provisional Government had re-commenced publishing the Weekly Irish Bulletin in late May 1922, resurrecting a key pre-Treaty republican propaganda tool, but in this iteration, it focussed exclusively on what was happening in Belfast and so was sub-titled (Belfast Atrocities). The first three issues, published each Monday, were crude, typewritten documents, but it became more sophisticated from mid-June, being properly typeset and printed. A separate London edition, simply titled Irish Bulletin, was published from 3 Adam St, the address of the London branch of the Dáil’s Publicity Department; it came out on a Wednesday and continued the numbering sequence of the original publication.

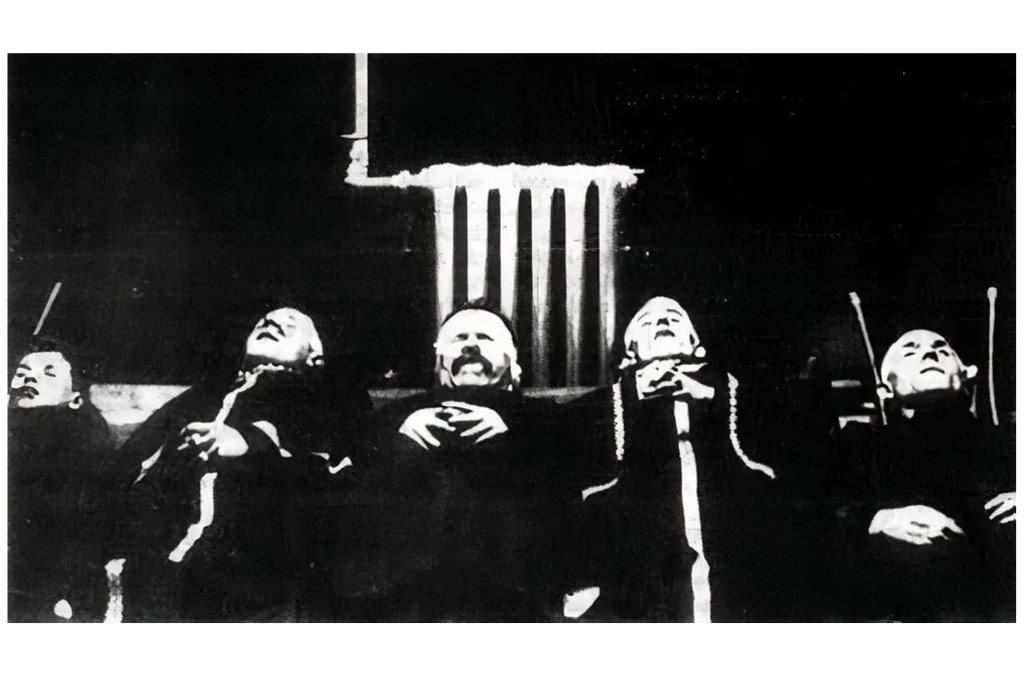

The London edition of 24 May which Wilson sent to Craig contained photos of the victims of the Arnon St killings, very similar in style to those of the McMahons previously published by the Freeman’s Journal.28

The composition of the most prominent photo directly – and most likely deliberately – mirrored that of the McMahons: it showed McCrory, Spallen, McKenna and Joseph Walsh, lying on what appear to be hospital beds or trolleys, indicating that it was taken in the Mater Hospital, to which the men’s bodies had been taken.

L-R: John McCrory, William Spallen, Bernard McKenna, Joseph Walsh (Irish Bulletin [London Edition] 24 May 1922); © PRONI CAB/6/89; reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI

This photo was accompanied by one of Michael Walsh, captioned “wounded by Orange gunmen”, which implies that it was taken early on 2 April, as he died later that day; there was also one of his infant cousin, Robert, lying dead in bed.29

L: Michael Walsh, fatally wounded in bed beside his father; R: Robert Walsh, his cousin, killed by a sniper the following day (Irish Bulletin [London Edition] 24 May 1922); © PRONI CAB/6/89; reproduced by kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI

There is one notable difference between the photos of the McMahons and those of the Arnon St victims. Within days of the McMahons’ funeral, the photos of those killed and wounded were published in the Freeman’s Journal. But over seven weeks elapsed between the attack in Carrick Hill and publication of the photos of those victims and even then, they only appeared in a relatively obscure propaganda bulletin in England – they were not published in the Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities) in Dublin, nor were they published in the mainstream press, either north or south, either before or after their appearance in London. Why was this?

The answer may lie in events in Belfast immediately prior to the publication of the photos in London.

On the night of 19 May, the IRA launched what would ultimately prove to be an abortive “northern offensive” when its Belfast Brigade made an audacious attempt to steal armoured cars, arms and ammunition from the largest police barracks in Belfast in Musgrave St. Although the plan failed, it prompted alarm among senior political, police and military figures in the north, who felt that a full-scale invasion from the south was now imminent. Three days later, on 22 May, a Unionist MP in the Parliament of Northern Ireland, William Twadell, was shot dead by the IRA in Belfast city centre as he made his way to his business premises.

The Provisional Government had mounted a successful political and propaganda campaign in the first part of 1922 to highlight the plight of Belfast nationalists, one that even drove the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, to admit to Churchill: “our Ulster case is not a good one.”30

But these latest events threatened to turn the tide of publicity in favour of the Unionist government. Some public relations victory was needed to restore momentum to an argument that placed unionism in a negative light – publishing the Arnon St photos offered the possibility of achieving that.

Conclusion

The immediate trigger for the Arnon St killings was the killing of Constable Turner earlier that night. But they came in the context of fury among loyalist policemen over the policing provisions of the Craig-Collins Pact. Whether the motive of the policemen from Brown Square Barracks for the onslaught in Carrick Hill was to simply avenge the dead constable or also to undermine the pact more generally, it certainly had the latter effect.

Whether or not the killing spree was personally led by DI Nixon – he cannot be placed at the scene as definitively as Constable Gordon – is largely immaterial. His proven track record in other similar incidents leaves no doubt that he would have approved of the actions of the men under his command on the night of 1 April: they killed four nationalist men and one boy.

Although it might be tempting to point to Nixon as the most obvious culprit and suggest that he must therefore also have been responsible for the Arnon St killings, to do so without evidence would only deflect attention from the wider network of regular policemen and Specials who acted alongside him. The so-called “great men of history” and the great bogeymen of history shared one thing in common: they both needed willing foot-soldiers.

Although the pact had trumpeted “Peace is today declared,” that proved to be a forlorn hope. After the killings in and around Arnon St, a further 151 people were killed in Belfast, making up 30% of the entire death-toll for the Pogrom.

I would like to thank the Deputy Keeper of Records, PRONI, for granting permission to reproduce the photos of the victims of the Arnon St killings in this post.

Edward Burke’s new book on the McMahon family killings, Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles, will be published by Merrion Press in September. I intend to review it in a future blog post.

References

1 Kieran Glennon, ‘You boys say your prayers – the McMahon family killings, March 1922’ in Tommy Graham (ed.) The Split: From Treaty to Civil War 1921-23 (Dublin, Wordwell Books, 2021).

2 Heads of Agreement between the Provisional Government and Government of Northern Ireland, 30 March 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

3 Michael Hopkinson, ‘The Craig-Collins Pacts of 1922: Two Attempted Reforms of the Northern Ireland Government’ in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 27, No. 106 (November 1990), p145-158.

4 Ibid.

5 Northern Whig, 4 July 1922.

6 Andrew Boyd, Holy War in Belfast (Belfast, Pretani Press, 1987), p202. Boyd did not provide a reference for this statement, nor have I found one.

7 Press room to Michael Collins, 3 April 1922, NAI, Northern Ireland outrages, TSCH/3/S11195.

8 Statutory declaration of Daniel Girwin, 3 April 1922, NAI, Northern Ireland minorities, NEBB/1/1/10.

9 Secret document, 10 April 1922, NAI, Stanhope St murders, NAI, NEBB/1/1/5.

10 Edward Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties: Loyalism and Paramilitarism Since 1920 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2024), p195; Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Ernest Blythe Papers, University College Dublin Archives (UCDA), P24/176; A few facts concerning murders organised and carried out by the Belfast police force in 1920-21, NAI, Northern Ireland outrages January-October 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

11 Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Ernest Blythe Papers, UCDA, P24/176.

12 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983) p329-330 n33.

13 Statutory declaration of Daniel Girwin, 3 April 1922, NAI, Northern Ireland minorities, NEBB/1/1/10.

14 Statutory declaration of William Kitson, 3 April 1922, ibid. McCrory’s surname was spelled “McRory” in some accounts, but I have chosen to apply the former spelling as it was more commonly used.

15 Statutory declaration of Catherine Hatton, 2 April 1922, ibid.

16 Statutory declaration of Gerald Tumelty, 2 April 1922, ibid.

17 Statutory declaration of Elizabeth Walsh, 2 April 1922, ibid.

18 Patrick J. Gannon, ‘In the Catacombs of Belfast’ in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 11, No. 42 (June 1922), p 279-295.

19 Belfast summary, n.d., NAI, Northern Ireland outrages January-October 1922, TSCH/3/S5462.

20 Statutory declaration of George Murray, 3 April 1922, NAI, Northern Ireland minorities, NEBB/1/1/10.

21 Anonymous to Michael Collins, n.d. (received 5 April 1922), NAI, Atrocities and Michael Collins, NEBB/1/1/9. The nationalist press also hinted in extremely vague terms that something else, other than shooting, had occured in the Walsh home: “[Mrs Walsh] found the innocent children were also victims of a crime, the details of which are so shocking that the mere repetition of it would send a thrill of horror through a person of the strongest nerve.” Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 8 April 1922.

22 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 8 April 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 5 May 1922.

23 Secret document, 10 April 1922, NAI, Stanhope St murders, NAI, NEBB/1/1/5.

24 Ibid.

25 James Craig to Michael Collins, 4 April 1922, NAI, Boundary Commission: general matters, TSCH/3/S1801A.

26 Northern Whig, 4 July 1922.

27 Henry Wilson to James Craig, 28 May 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

28 Irish Bulletin (London Edition) No. 25, 24 May 1922, ibid. The issues of the Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast Atrocities) published in Dublin on 22 and 29 May were both typewritten and even after typeset printed issues began to appear from 12 June, they carried no photos; NAI, Weekly Irish Bulletin (Belfast atrocities), TSCH/3/S10557.

29 Irish Bulletin (London Edition) No. 25, 24 May 1922, (PRONI), Correspondence and papers re Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, CAB/6/89.

30 Ronan Fanning, Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922 (London, Faber & Faber, 2013), p330.

Leave a comment