Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

Introduction: the republican counter-state

As the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) abandoned many of its smaller, more isolated barracks during 1919 and instead consolidated its personnel into large, fortified barracks in the main towns, a policing vacuum was created: “… republicans noted that the withdrawal of the police had created a situation where ‘undesirable persons’ took advantage of the ‘position that maintained’ for ‘looting and robbery.’ The IRA felt forced to respond.”1

Initially, the IRA simply added a policing role to its other activities, but from June 1920, a separate Irish Republican Police force was established, although there were overlaps in terms of personnel. This situation led the arch-conservative British paper The Morning Post to deride the Republican Police as “nothing but the Irish Republican Army with a different coloured muffler and the tail of their shirt projecting from a different part of their pants.”2

The Republican Police were strengthened in late 1921:

“Further reorganisation took place in June 1921 when it was decided that a ‘police force to the number of ten in each Company area’ be detached from the Volunteers. New general orders to re-organise a distinct republican force were issued in November 1921, by which time a truce had been in place for several months.”3

Irish Republican Police membership card from Limerick (National Museum of Ireland, HE:EWL.381)

As well as a police force, the republican revolution also established its own courts.

Agrarian agitation and land conflict began increasing in the aftermath of the Great War but, “Republican leaders viewed forced land distribution as divisive, difficult to control and threatening its cross-class national front strategy.”4

The Dáil responded by instituting Arbitration Courts in each county from June 1919. Then, “One year later, on 29 June 1920, Dáil Éireann determined on a programme of superseding British institutions in Ireland; it abolished the arbitration courts in favour of a full-scale parallel courts system.” These parish, district, circuit and supreme courts were collectively known as the “Republican Courts” and they won popular approval as resistance to British rule continued to spread.5

The sentences passed by the Republican Courts were enforced by the Republican Police, although this entailed its own problems:

“Civil cases were easy for the republicans to manage, but criminal prosecutions posed greater difficulties … IRA detention of criminal suspects was a burden for the organisation, since prisoners had to be kept beyond the reach of the police … While short term detention was practical, the IRA could not maintain prisoners over long periods … Public shaming was used for less serious offences like larceny. Shaming ranged from public apologies and verdict announcements at public events, to the tying of offenders to church gates on a Sunday, accompanied by a sign announcing their crime … ritualised communal violence, such as cutting of women’s hair or tar-and-feathering of men, seemed mainly confined to crimes committed against the IRA, such as informing or socialising with the Crown forces. Similarly, the death penalty was very frequently deployed against suspected civilian informers, but virtually unheard of for criminal offenders.”6

Earliest appearances in the north

In the north, where the unionist population was in the majority, the RIC and the British judicial system obviously did not suffer similar withdrawals of public support to those encountered in the south and west. Nevertheless, attempts were made to establish the republican counter-state in the north. In Tyrone, a Magherafelt man was arrested in September 1920 for having presided over a Republican Court, while courts were established in Monaghan in the same month; the following month, documents relating to Republican Courts were seized at Warrenpoint in Down.7

The Truce of July 1921 gave both additional impetus to the effort to embed Republican Courts across Ireland. At the Sinn Féin ard fheis in August, Minister for Home Affairs Austin Stack said, “… he knew of no activity, except the IRA activity, which had consolidated the Republic and damaged the enemy prestige more than the functioning of the courts.”8

A Republican Court in session

Following this, Republican Courts were set up in Derry city in September. In Armagh, in November, two pedlars were found guilty of theft and sentenced to two days’ imprisonment by a Republican Court; they were subsequently rescued by the RIC from a makeshift jail in Keady.9

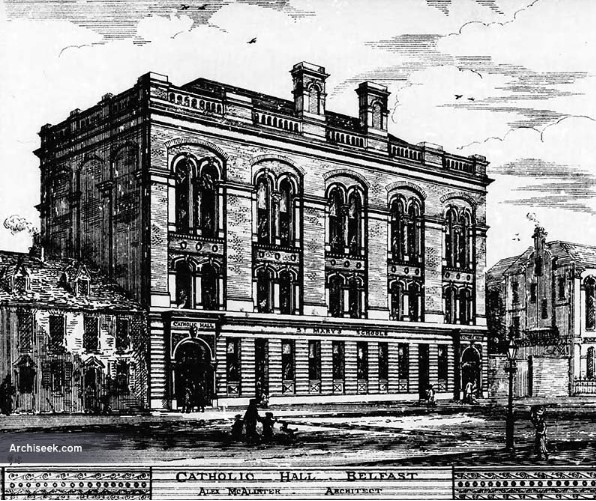

The only documented reference to a Republican Court in Belfast in this period was in an item captured by the RIC in a raid on St Mary’s Hall in Bank St in the city centre; this hall doubled as the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division headquarters and its Truce Liaison Office for Belfast. The document was a “Statement, dated 4/7/21, of case to be tried by Dail Eireann Arbitration Court, between Patrick J. Cleary, 25, Moyola Street and Henry Osborne, Gibson St., both Insurance agents.” Notably, this case pre-dated the Truce.10

In August 1921, Belfast saw the first appearance in public of the city’s Republican Police:

“Yesterday morning the police authorities in Belfast were informed of an extraordinary occurrence which took place on Tuesday night, four young men – all Roman Catholics – having been kidnapped and conveyed to an unknown destination … The streets mentioned are all in the Roman Catholic area of the city commonly known as the Low Market. The missing men were taken away in taxicabs by armed men. It is stated that they were ‘arrested by Sinn Fein police,’ and it is presumed that they will be tried by a Sinn Fein court. No information could be obtained as to the ‘offence’ they are alleged to have committed.”11

Two months later, two other men were arrested – coincidentally from the same area; this may reflect a particular dedication to duty by the Republican Police in the Market or – more likely – the fact that journalists had a particularly talkative source in Musgrave St RIC Barracks, which was responsible for policing that part of Belfast:

“Two young men named Robert Johnston, 18, Welsh Street, and Patrick Pierce, 27, Stanfield Street, were abducted from their homes on Tuesday evening by men who were stated to be ‘Sinn Fein police.’ They were hurried off in motor cars, and their wives later received communication informing them that food could be brought to the ‘prisoners’ at a hall near the city centre.”12

Although there had been little let-up in the sectarian violence following the Truce, the Republican Police evidently had enough time on their hands to intervene in domestic disputes – in December, “During the afternoon Sinn Fein police entered the house of a man named Patrick McAniff and ‘cautioned’ him for quarrelling with his father-in-law. One of the intruders produced a revolver, but they made no attempt to injure McAniff.”13

Just before the end of 1921, in keeping with the wider national re-structuring, attempts were made to regularise the Republican Police in Belfast, putting at least its senior officers on a full-time footing – one memo seized in St Mary’s Hall was from “Chief of Police to O/C Police 1st Bgde., 3rd N. Divn. making arrangements for paying Bgde. Police Officer, date 29/12/21.” The following day, the Belfast Brigade O/C Police wrote to the O/C Police of the 2nd Battalion, asking him to attend a meeting in St Mary’s Hall on 31st December. These fragments demonstrate that there were dedicated IRA officers, down to battalion level, in charge of policing.14

The jail at St Mary’s Hall

The newspaper reports on the arrests of men from the Market indicated that they were being detained at a city centre location. This was most likely to have been St Mary’s Hall in Bank St, which was large enough and had enough rooms to use as cells. Evidence for its use as a republican jail was provided by one of the Special Constables who raided it in March 1922: “Secreted in a cupboard in another part of the building I found a number of leg-irons and chain handcuffs.”15

St Mary’s Hall in Bank St was used as a jail by the Republican Police

One of the jailers was an IRA member named Patrick Brady, who later gave intriguing testimony that not all the prisoners held there were civilian criminals:

“Q: You did duty as armed guard in Divisional Prison; were you arrested?

A: We had a prison of our own in Belfast.

Q: Were they Specials?

A: They were all kinds – thieves, and Specials, etc. We had a B Special that particular time that I was up. We let him off and took him blindfolded and released him at a place called Santry (?) Park.”16

Although he was not a member of the IRA, a man named James McStravick also appears to have acted as a Republican Police jailer – he was certainly interned for having done so. McStravick was arrested the day after his son, who was in the IRA, was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for possession of a revolver and ammunition.

Despite a letter from the Ancient Order of Hibernians stating that James McStravick was one of their members and “an uncompromising opponent of Sinn Fein”, the Royal Ulster Constabulary insisted that he had detained common criminals on behalf of the IRA Truce Liaison Office in St Mary’s Hall. This assertion was made on the basis that, “information was received from a person whom the police suspected was implicated in crimes of an ordinary character, including larceny, hold-ups &c, and for which he was arrested by the IRA.” In short, McStravick was informed on by a criminal who had run foul of the Republican Police.17

St Mary’s Hall was not the only jail in Belfast operated by the Republican Police. When the RIC and troops from the Norfolk Regiment raided a property in Hardinge St in the New Lodge on 15th March 1922, as well as handcuffs, they also found a “Set of leg-irons attached to an iron bar along the wall.” There was also a makeshift jail in Kent St in the Carrick Hill area.18

“… Without warrant or authority arresting and detaining …”

A man named Arthur Hunt achieved the distinction of being the first person to be arrested by both the RIC and the Republican Police. In the summer of 1921, he was arrested by RIC Constable Andrew McCloskey:

“I was the first to arrest Hunt, Head Constable Brennan was with me. Hunt posed as being an Auxiliary. He produced an application form to try to bluff us. We caught him one morning during the Curfew before 5 o’clock. On searching him we found a U.V.F. five chamber revolver fully loaded and around the band on the rim of his hat I got a bandolier and 20 rounds of dum dum flat nosed ammunition …. I scrutinised his note and found there the names of several Catholics. The words Sinn Fein were after their names. The Head Constable was ordered to prosecute him, on being convicted he was fined five pounds … He had the audacity after that to go back to the Barracks looking for his revolver.”19

Then, in late October 1921, Hunt was arrested by the Republican Police and admitted responsibility for the armed robbery of a breadserver: among the items captured in St Mary’s Hall were, “Signed statements of Hunt admitting guilt in ‘holds-up’, witnessed by Hugh Boyle, 44 McDonnell St, 28/10/21.”20

On 6th November, the RIC raided the location in Kent St where Hunt was being held, thus beginning a process that culminated in the show trial of an ever-growing number of IRA members, colourful yet risible witness testimony and the defendants seeking to inject an element of pantomime into proceedings.

The raid that freed Hunt was led by District Inspector John Nixon of Brown Square Barracks, who had responsibility for the Carrick Hill area of north Belfast in which Kent St was located. Three IRA members – Patrick Loughran, James Cunningham and James Carroll – were arrested at the scene and charged with conspiracy to murder Hunt. The three refused to recognise the court and were remanded for a week.21

Days later, the Dáil Publicity Department issued a statement, stung into action by excited reports about the Kent St raid in the London press while the Treaty negotiations were in progress:

“This man was arrested by I.R.A. police on a charge of robbery and hold-up. He made two voluntary statements, which I now hold, admitting these robberies. In accordance with liaison instructions, he was to be handed over to the R.I.C., together with any evidence in our possession. The fact that he was Protestant has nothing whatever to with the case. There is absolutely no truth in the statement which appeared in the London Press, and other papers, that this man was tried, or that he was to be executed.”22

The next hearing in the case was on 15th November but by then, the number of defendants had swollen to seven as four more IRA members had been arrested and also charged with conspiracy to murder: Patrick Welsh, Hamilton Young, Henry O’Neill and Ambrose Largey. “All the accused assumed an indifferent and callous attitude.”23

This hearing was also noteworthy for the testimony of Hunt, who vividly – if not imaginatively – described his experiences. He said that on 22nd October, he had been taken to a meeting in Alton St with Robert Brennan, captain of the IRA company in Carrick Hill – Brennan pulled a revolver on him and told him, “You are in the hands of the Republican forces. I suppose you know this is quite legal, and independent of the foreign Government.” Brennan accused him of the armed robbery of the breadserver and other charges. Hunt said he was then guarded by a succession of IRA members, who he named, but not all of whom had yet appeared in the dock. While he was in captivity, another prisoner had been brought in, bleeding and accompanied by Young, who had apparently arrested him in Ballymacarrett.24

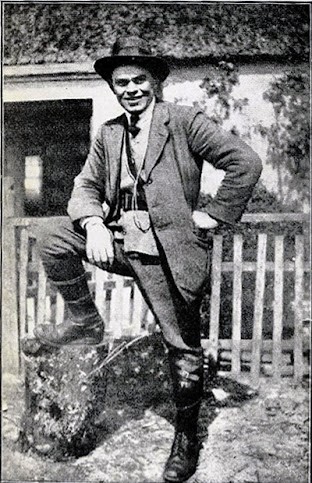

“Tomorrow night you’ll be playing a harp.” Robert Brennan, a Connaught Ranger during the Great War, was the captain of the IRA company in Carrick Hill (photo courtesy of 6th Connaught Rangers Research Group)

Hunt said that two days later, he had been blindfolded, put in a taxi and driven to a hall elsewhere in the city: “… he heard the bolts of rifles being worked, and expected to be shot any moment.” His captors helpfully removed the blindfold so he could observe the proceedings of a supposedly clandestine revolutionary army and “… he saw about twenty or thirty rifles in the hall, and about the same number of men wearing leggings and green trousers.” Nobody appears to have said anything to Hunt on this occasion, although “… about 2.30 in the morning [he] was wakened and struck on the head with the flat end of a hatchet, which cut him.”25

A week after that, on 1st November, he was blindfolded once more, driven in a taxi under armed guard for several hours, then brought into a railway station and put on a waiting train. There were British soldiers in the station but Hunt claimed he did not cry out for help as they were not armed, whereas his IRA guards were. After “about 12 minutes” – note, not “about 10 or 15 minutes” – he was bundled back into the taxi and driven a short distance, the train journey apparently having been unnecessary after all. He wound up at a “Sinn Fein camp” near Dublin, which had about 200 armed men and 50 to 60 other prisoners. For added drama and to inject an extra whiff of sulphur, the camp commandant was allegedly none other than Dan Breen.26

Arthur Hunt claimed that Dan Breen was the commandant of a prison camp to which he was taken

On 3rd November, a guard in the camp told him he was going to be shot. But on 5th November, he was blindfolded again and driven back to Belfast; along the way, he was told once more that he was going to be shot, although nobody seemed in any particular hurry to pull the trigger. He wound up in Kent St and was once more met by Brennan, who told him “We are going to dispose of you next week.” Innocently, Hunt asked, “Thank God; what’s the fine?” Brennan said, “There is no fine in this case. You may say your prayers.”27

Hunt said that the following night, Brennan came to see him again and asked, “How are you feeling now?” It seems like a highly unusual line of conversation to tell someone they are going to be shot and then enquire about their emotional wellbeing. But ever the optimist, Hunt replied “Not so bad. What about getting off?” Brennan shattered his illusions: “There’s no off in the case this time. Tomorrow night you’ll playing a harp.” Luckily for Hunt, the RIC raided the jail later that night, coming to his rescue in the nick of time.28

A further court hearing followed on 18th November, when four more IRA defendants were added to the now-bulging dock: Stewart Kane, James Joseph Cole, Daniel Henry, and Patrick Bums. They were charged with committing the original armed robbery to which Hunt had apparently admitted, but for good measure, a charge of conspiracy to murder was added. In a case of confession and counter-confession, an RIC Constable read a statement made by Henry, admitting to the robbery.29

Having already refused to recognise the court, the eleven prisoners turned their backs on the magistrate and refused to remove their caps.

“They were invited by the District-Inspector not to create a scene, and the Resident Magistrate appealed to them to observe decorum. The prisoners ignored these requests … Further appeals to the men in the dock to accord with the proprieties of the Court failed. One of the contingent continued smoking with a defiant air, and the din became so disturbing that the proceedings of the Court were interrupted.”30

Attempts to get the defendants to pipe down and face the right way failed, as there were simply too many prisoners and not enough police – so police reinforcements were sent for. Meanwhile, “Burns smoked on with unabated vigour.” Eventually, Burns held his cigarette down by his side and, “in a brief reign of comparative immunity from interruption the hearing was proceeded with.” DI Nixon made a brief statement, claiming that when arrested and charged, Burns had blurted out, “l wish we had murdered him.” The defendants were once more remanded, but “When leaving the dock, they made much noise as they possibly could.”31

On 24th November, yet another defendant was added to the list – Henry McGraw from Ballymacarrett, who Hunt had said was another of his Kent St guards. Hunt claimed McGraw had boasted of having beaten a charge of murder – he had, in fact, been acquitted the previous January.32

Having gone through all these hearings in the Custody Court, the twelve defendants were eventually sent forward for trial at the City Commission, where they appeared on 5th December. By this time, it appears the charge of conspiracy to murder had been dropped, as they “… were arraigned on a charge of conspiring to bring into contempt the laws of his Majesty the King in Ireland, and without warrant or authority arresting and detaining Arthur Hunt, and further, with causing him bodily harm.” In other words, they were prosecuted for being members of the Republican Police.33

After another remand, the case was finally heard before the Lord Chief Justice, Denis Henry, on 13th December. Perhaps predictably, when Hunt was called on to testify, his “… entry into the witness box was greeted with laughter by the prisoners.” The judge provided a thundering summing-up which left the jury in no doubt of the verdict he expected to hear: “Hunt was to be shot like a dog for the alleged offence of holding-up a breadserver. That was be made a capital offence at the hands of these men – just look at them, the men who were going to administer a capital sentence!” The twelve were found guilty and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.34

Hunt’s fortunes did not improve after the trial. According to Constable McCloskey, who had first arrested him the previous summer, he was brought to Brown Square Barracks and was allowed to remain there for his own safety for a number of months, but:

“Owing to his conduct in the Barracks where he was continually stealing revolvers and ammunition he made the pace too hot even for Nixon, they put him out of the Barracks. He was afterwards a patient in the Mater Hospital, as a result of having tried to hold a man up. The man attacked closed with Hunt, who got shot by his own revolver.”35

“Robbers and thieves beware – IRA”

The first appearance in 1922 of the newly structured Belfast Republican Police was not in response to crime, but rather to deal with a more cultural issue. The newspaper report on the incident is worth quoting in full, if only for the wonderful conclusion:

“Some time ago the promoters of a dancing class which meets weekly in the Falls district of Belfast were warned by Sinn Fein ‘police’ that, if they persisted in allowing English dances to be performed there the place would be closed, the ‘boycott’ of English goods now apparently extended to English amusements. No heed was taken of the threat, but while a dance was in progress in the Hibernian Hall in Clonard Street last night about 8-30, a party of Sinn Feiners entered and took possession.

The members of the class were in the midst of a two-step when they were peremptorily ordered to desist by the raiders. The participants thereupon left the building, and on the matter being reported to the police a party of military and police proceeded to the hall, but on arrival they found that intruders had taken their departure. Dancing was not resumed.”36

In February, “… republican police in the Catholic Ardoyne area arrested a petty thief and sent him, together with a note and his loot to the RIC, who duly prosecuted him. The magistrate, however, dismissed this case.”37

The following month, two men from the Lower Falls were arrested by the Republican Police for armed robbery; after the suspects were identified by an eye-witness at a house where they were being interrogated, they were then handed over to the RIC for prosecution. As the men’s revolver had been retained for use by the IRA, there was insufficient evidence to convict them so they were acquited.38

Scene of the English two-step in 1922: the Clonard Hibernian Hall today

Rebuffed by the authorities on these occasions, the Republican Police then began enforcing sentences themselves and the spring of 1922 saw their activity focussed on the Falls Road.

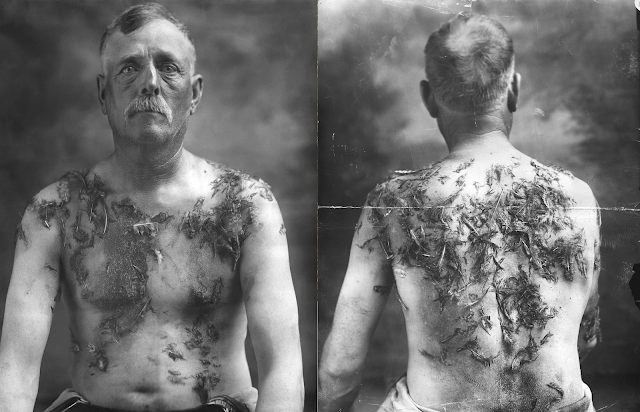

Tarring and feathering was a punishment dating back to medieval times: the person would be stripped to the waist, their head shaved, have pitch or tar poured over them, then doused in feathers and paraded in public. In early 20th century USA, it was used as a form of vigilante punishment against Germans during the Great War, in racist attacks on African Americans and in attempts to intimidate trade union members during labour disputes.

A German man after being tarred and feathered in the USA during the Great War

In April 1922, four men held up and robbed a rent collector of 16 shillings:

“They were followed, arrested, and taken to an unknown destination by some of the residents. When they were searched each man was found have 4s in his possession. They were subjected to a trial, and, having been sentenced, were subsequently tarred and feathered.

Their coats and caps having been taken off, their hands were fastened behind their backs, and, with the notice ‘Robbers and thieves beware – IRA’ pinned to them, they were marched along the Falls Road. When passing the Baths one made a dash inside, and the others bolted and managed to get into a house in Omar Street, where they remained till the military arrived.”39

Five days later, a man named Anthony Canning was similarly punished for the armed robbery of £20 from a shopkeeper. Afterwards, he was brought to the Royal Victoria Hospital and, while still covered in tar and feathers, was then arrested by the RIC. Evidence given at his trial by a detective would indicate that Canning had been one of the four men previously tarred and feathered:

“This is one of the men who was tarred and feathered on the Falls Road some days ago?

Witness – Yes.

Do you know who was responsible for that ? No.

Is there any connection between the tarring and feathering and this case? There appears be.

Do you suggest that the tarring and feathering was for this offence? I would say for a similar one.”40

Having already been sentenced to being tarred and feathered by the Republican Police, Canning was then found guilty a second time and sentenced to three years in prison and 15 strokes of the birch.41

In early May, the practice of tarring and feathering criminals received public support from a most unlikely source: following the armed robbery of a tram conductor at the corner of Panton Street and the Falls Road, the Belfast Telegraph reported the incident under a headline that read, “Tar and feathers needed for four blackguards on Falls.”42

Two days later, an internal RIC report noted another public punishment, this time back in the Market:

“At 5 p.m., a horse and lorry containing driver and five other men came from Albertbridge to Cromac Square. Four men were put off, two of whom had been tarred and feathered. These men ran away – one into Market Street, and the other into No. 5 Cromac Square – the Police searched No. 5 but could not find the man. His name was given to the Police … The other man is said to come from about Corporation Street. The latter was said to be handcuffed. Believed to have been punished by the IRA for ‘hold ups’ in the City.”43

In early June, “… a man was tarred and feathered and tied to the railings of Dunville Park, Falls Road. A crowd collected, which the military dispersed, and someone released the victim, who quickly disappeared.”44

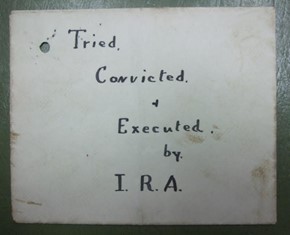

Informers

As well as dealing with ordinary crime in their Republican Police guise, the IRA was also intent on stamping out the practice of informing. Only one informer was killed in Belfast during the Pogrom, a man named Samuel Mullen.

Mullen had been employed in the shipyard until he was expelled along with thousands of his co-workers on 21st July 1920. On the afternoon of 29th March 1922, he was queueing outside the Hibernian Hall on the Falls Road, waiting for a relief payment from the White Cross Organisation. “While in his place, Mr. Mullen was approached by a number of men who induced or compelled him to leave the queue and he walked off with them along the Falls Road.” His body was found on the Whiterock Road later that day.45

Mullen was shot by James Cassidy, an IRA member from Ardoyne, who described the killing:

“His name was Mullen and I had to get two others – three of us took him on and I had a place on the Falls Road … There was confirmation of identification; that was why we had to take him there and then we took him up into the country. He was already found guilty. He lived in the Ardoyne area.

Q: You shot him then?

A: We had to find ways and means of taking him away. We took him up to the foot of the Divis [Mountain] and we gave him every opportunity to let us know what he knew. I had nothing else to do but tell the others to stand back and we gave him a fair crack of the whip. I administered the coup de grace.”46

In July of that year, John Gaffney of the Market company of the IRA was sentenced to twelve months in prison after he was caught in possession of documents warning suspected informers:

“The document, which was headed Oglaig [sic] na h’Eireann, read: ‘I wish to inform you that we will take immediate action against you regarding accepting money from Crown forces, also to being seen giving information to the Crown forces by being seen in the company of Specials, and showing good feeling towards the enemy. We can prove by witnesses that saw you doing so. We now hope that this is sufficient warning, otherwise drastic measures will have to adopted.’”47

The irony was that by the time Gaffney was captured, the IRA in Belfast was in such disarray that there was relatively little information for anybody to divulge to the police.

Summary & conclusions

The information available about the Belfast Republican Police is very fragmentary – they seem to flit through the shadows of the Pogrom, only making occasional appearances. In the north, the British legal system and the RIC continued to enjoy majority public support, so unlike other parts of the country, there was no legal vacuum into which the Republican Courts and Police could step. This was particularly the case in Belfast, so they were forced into a much more subterranean existence than elsewhere.

At brigade and battalion level, individual IRA officers were designated to act as O/Cs Police, although their rank-and-file policemen were simply IRA members temporarily wearing a Republican Police hat – for example, Robert Brennan, captain of the Carrick Hill company. Their operations were reasonably sophisticated, even extending to the running of detention facilities in St Mary’s Hall and elsewhere.

The Arthur Hunt case was the most high-profile occasion on which the Republican Police were dragged into the daylight and it resulted in the jailing of a dozen active IRA members. It is hard not to see that as having been the original objective of an elaborate RIC sting operation.

Many aspects of Hunt’s testimony in court were intended to be theatrical but were clearly ludicrous, the alleged involvement of Dan Breen being a particularly wild embellishment, but conveniently for the RIC, Hunt named all those who had guarded him at various stages – including three who were not arrested and charged. Those who he named were from different parts of the city – Hamilton Young and Henry McGraw were from Ballymacarrett east of the Lagan, all the others from Carrick Hill in north Belfast; Hunt’s statement therefore allowed the RIC to rein in various wanted IRA activists in a single swoop.

The Military Service Pension files of three of the IRA/Republican Police involved in the case have been released – Robert Brennan, Patrick Loughran and Patrick Burns – but frustratingly, Brennan makes no reference at all to the incident, while both Loughran and Burns only refer to it in passing as being the reason for their imprisonment and refer to Hunt as being a police spy rather than an armed robber; this may have been to add weight to their pension applications. None of them address one obvious question the IRA must have asked relating to the affair: how did the RIC know where to go when they set out to rescue Hunt?48

The activities of the Republican Police in 1922 point to a certain level of acceptance of their role by the nationalist community, although the participants in the English two-step dance class in Clonard were an obvious exception. The sequence of public tarring and feathering incidents suggest at least the gathering of evidence and carrying out of sentences for robberies, although there is nothing to substantiate a conclusion that these cases were tried before Republican Courts, as opposed to being decided by the Republican Police themselves.

However, the nationalist community did not universally accept the role of the IRA/Republican Police, and so informing was an issue that had to be addressed. The killing of Samuel Mullen did not act as a complete deterrent and as the summer of 1922 wore on, the prevalence of informing increased.

In general, we still know very little about the Belfast Republican Police, especially relative to other aspects of the Pogrom period. Future releases of files from the Military Service Pensions Collection offer the only potential prospect for filling in some of the gaps.

References

1 Brian Hanley, ‘Republican policing and the Irish revolution,’ in Anne Dolan & Catriona Crowe (eds), ‘A Very Hard Struggle’ – Lives in the Military Service Pensions Collection (Dublin, Department of Defence, 2023), p64-81.

2 Northern Whig, 31st October 1921.

3 Hanley, ‘Republican policing.’

4 John Borgonovo, ‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and the Irish Revolution 1919-1921’ in Justice and Society, Vol. V, Justice in Wartime and Revolution (Brussels, National Archives of Belgium, 2012), p49-65.

5 Eda Sagarra, Kevin O’Shiel – Tyrone Nationalist and Irish State-Builder (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2013), p132.

6 Borgonovo, ‘Republican Courts.’

7 Belfast News-Letter, 9th & 27th September 1920; Belfast News-Letter, 18th November 1920.

8 Northern Whig, 24th August 1921.

9 Belfast News-Letter, 21st September & 21st November 1921.

10 Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/32/1/130.

11 Belfast News-Letter, 25th August 1921.

12 Northern Whig, 20th October 1921.

13 Belfast News-Letter, 12th December 1921.

14 Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, PRONI HA/32/1/130.

15 Report of Special Constable Norman McSpadden, 17th July 1926, in Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, PRONI HA/32/1/130.

16 Patrick Brady, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives (MA), MSP34REF6162. I could find no reference to a Santry Park in Belfast at that time, so it is likely the stenographer misheard what Brady said; the closest phonetic equivalent would be San Souci Park, off the Malone Road, but this seems improbable.

17 McStravick, James, Stanfield St, Belfast, PRONI, HA/5/1494.

18 Belfast Telegraph, 16th March 1922.

19 Statement of Constable Andrew McCloskey, Northern Ireland outrages, National Archives of Ireland (NAI) TSCH/3/S11195. There is no record of Hunt’s conviction in the Belfast newspapers: it may be that because Hunt was a police informer, the newspapers were discretely asked not to mention it.

20 Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, PRONI HA/32/1/130.

21 Belfast News-Letter, 9th November 1921.

22 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 19th November 1921.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 16th November 1921.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Belfast Telegraph, 19th November 1921.

30 Belfast News-Letter, 19th November 1921.

31 Ibid.

32 Northern Whig, 8th January 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 16th November 1921; Northern Whig, 25th November 1921.

33 Belfast News-Letter, 6th December 1921.

34 Northern Whig, 14th December 1921.

35 Statement of Constable Andrew McCloskey, Northern Ireland outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

36 Belfast News-Letter, 19th January 1922.

37 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983) p325 n3.

38 Northern Whig, 21st March 1922.

39 Northern Whig, 21st April 1922.

40 Northern Whig, 26th April 1922.

41 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 26th August 1922.

42 Belfast Telegraph, Friday 5th May 1922.

43 Occurrences in Belfast, 7/5/1922, in File of reports by R.I.C. on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A.

44 Belfast News-Letter, 5th June 1922.

45 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 8th April 1922.

46 James Cassidy, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10852.

47 Northern Whig, 21st August 1922.

48 Robert Brennan, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10852; Patrick Loughran, MSPC, MA, 24SP9836 & DP5449; Patrick Burns, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF6062.

Leave a comment