The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) are the subjects of few dedicated books. Two offer very partisan views, one positive and one negative – Arthur Hezlet’s The ‘B’ Specials – A History of the Ulster Special Constabulary and Michael Farrell’s Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27.

There is no archival material freely available on the force that is comparable to the nominal rolls of IRA membership that form part of Military Archives’ Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), although in recent years, some researchers have been allowed limited access to such files. This post introduces another fragment – a 1922 IRA intelligence report on members of the Specials in Belfast.

I am deeply grateful to John Dorney of www.theirishstory.com for drawing my attention to this series of files in Military Archives.

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

The origins of the Special Constabulary

In early 1920, as the War of Independence grew in momentum and began to approach the north, leading unionists were alarmed – they felt that the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was neither willing nor able to fight the insurgency properly; much of their distrust stemmed from the view that the force had too many Catholics in its ranks for it to be politically reliable. “It seemed clear that, as little help could be expected from Dublin or the RIC, the loyalists would have to arm and protect themselves.”1

Their solution was to revive the old Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) – in a diary entry in late July 1920, the man who had carried out the organisation’s gun-running at Larne in 1914, Fred Crawford, noted,

“Some eight weeks ago I got D.[Dawson] Bates to call together the leaders of the U.U.[Ulster Unionist] Council and to formulate a policy, as the rank and file thought they were going to be left to look after themselves. The outcome of this meeting was to ginger up the Unionist Clubs and to enrol for the U.V.F.”2

That places the discussion as happening in late May. After Carson’s incendiary speech on the Twelfth, in which he stated, “We will re-organise, as we feel bound to do in our own defence, throughout the province the Ulster Volunteer Force – (loud cheers),” the revival accelerated. “By October, there were fourteen or fifteen UVF battalions in Belfast alone.”3

Edward Carson arriving at the Field in Finaghy on the Twelfth, 1920; his speech there helped accelerate the revival of the UVF

However, the legal standing of the UVF was decidedly ambiguous, to put it mildly. To address this problem, after the rioting that followed the shipyard expulsions of 21st July, and particularly after the IRA’s killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn on 22nd August, unionist leaders urged the British government to establish a Special Constabulary in the north.

Their intention was that the new force would be much more reliably manned than the RIC – the secretary of the Ulster Unionist Council, Richard Dawson Bates, had previously said, “The old formation of the UVF could be used for the purpose.” James Craig blithely assured London that, “Ulster would not … terrorise the Roman Catholics and would not allow mob rule. Ulster would be able to prevent the Protestants running amok.”4

On 9th September, the British cabinet decided to proceed with the formation of the Special Constabulary and recruitment began on 22nd October.

The new force was organised into three classes: A Specials were full-time, paid and worked alongside the regular RIC; B Specials were part-time and unpaid, but with their own command structure separate from that of the RIC, which meant that they operated according to their own orders; C Specials were part-time, unpaid, non-uniformed and were generally used for guard duties. The authorised strengths for each class were 2,000 As, 19,500 Bs and 8,000 Cs.

But in July 1921, under the terms of the Truce, the B Specials were demobilised, much to unionists’ disgust. As a result, membership of loyalist paramilitary organisations expanded, such as the Ulster Imperial Guards, who first publicly demonstrated their presence with a series of church parades on 13th November 1921. Within a week, they claimed to have over 21,000 members, with the ambition of increasing this to 150,000 within three months.5

Meanwhile, Crawford once more urged the resurrection of the UVF, telling Craig, “It is better to have the old U.V.F. pulled together with its traditions and discipline than have irresponsible individuals enlisting a lot of scallywags who will only be a menace and a danger to our cause.”6

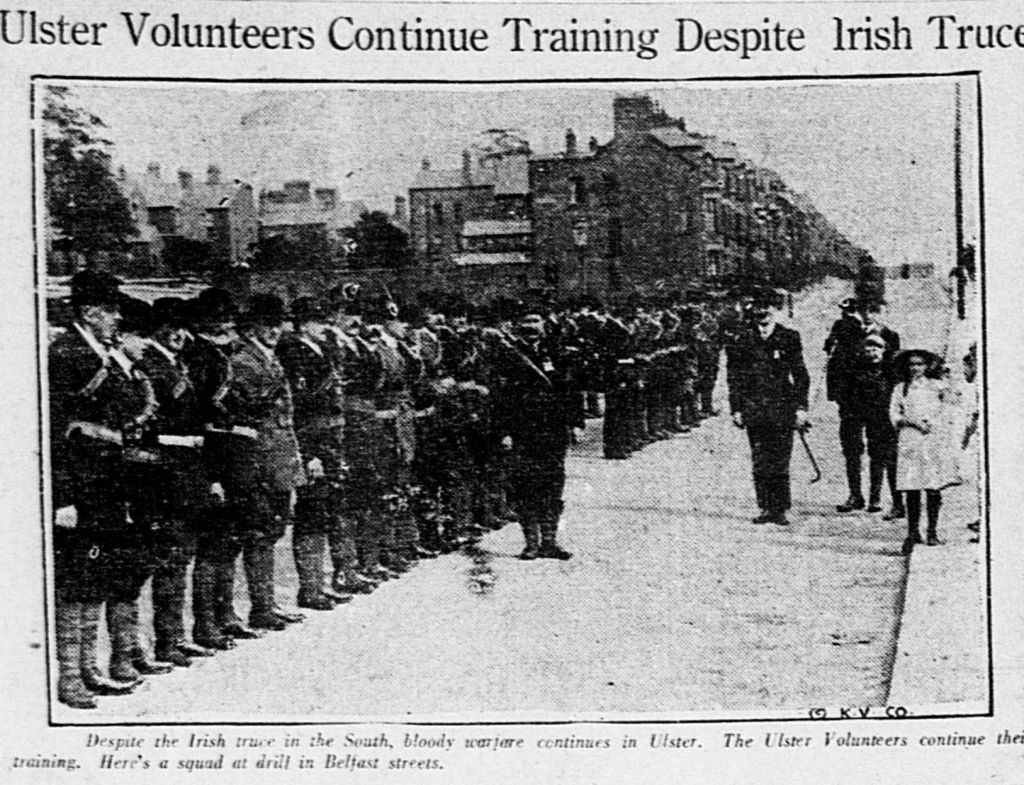

The UVF was given fresh impetus by the demobilisation of the B Specials under the terms of the Truce of July 1921 (Columbian Evening Missourian, 15th September 1921)

The RIC had also noted these developments and in preparation for the handing over of security and policing powers to Craig’s Northern Ireland government, the RIC Divisional Commissioner, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Wickham, issued a memo:

“Owing to the number of reports which have been received as to the growth of unauthorised Loyalist defence forces, the Government have under consideration the desirability of obtaining the services of the best elements of these organisations.

They have decided that the scheme most likely to meet the situation would be to enrol all who volunteer and are considered suitable into Class ‘C’ and to form them into regular military units.”7

As the Truce forbade both the Irish and British sides from forming new military units and the Government of Ireland Act forbade the Northern Ireland government from raising any military force, the British government demanded the proposal be withdrawn. It was temporarily shelved but the B Specials were remobilised after policing became a Northern Ireland government responsibility on 22nd November.

In the spring of 1922, Wickham’s proposal was dusted off and a new C1 class of the Specials was created on the lines he had originally advocated.

“Craig argued that they could rely on arms already in the north … What he had in mind became clear in March 1922, when … it emerged that his government had an arrangement with the Imperial Guards for that organisation to supply the ‘C’ Specials with arms when the need arose.”8

C Specials in Chichester St; the C1 Specials were recruited from loyalist paramilitary organisations

The strength of the Specials was expanded in a series of increments – in March, the B Specials were increased to 22,000 and in April, Craig’s government approved plans to increase the A Specials to 7,500 and the C Specials to 27,000.9

The origins of the IRA document

As detailed in a previous blog post, The IRA spy who joined the Specials, in the summer of 1922, the IRA succeeded in placing a mole named Pat Stapleton in the office of Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood, the Military Advisor to the Northern Ireland government; Solly-Flood’s department shared the Waring St headquarters of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). In the evenings, Stapleton would “borrow” files from the office, hand them over to the IRA to be transcribed overnight and then replace them in the morning.10

On 19th August 1922, Stapleton stole a number of files from Solly-Flood’s office, passed them on to David McGuinness, the Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, and then promptly absconded south of the border. These files were then brought to the headquarters of the Free State army at Beggar’s Bush in Dublin by Séamus Woods, O/C of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division.11

Naturally, the disappearance of both Stapleton and the files prompted a frantic investigation by the RUC. They established that 14 files were missing – but none of them were titled “List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters.”12

Stapleton was not the IRA’s only source of inside information on the police. A network of sympathetic policemen would also pass on intelligence, as outlined by Desmond Crean, an IRA Intelligence Officer from Ardoyne:

“… got in touch with Detective Sergt. Michael Furlong, Constable Monaghan was another and Constable McCluskey and probably one or two others. In other words, there was a crowd, and [we] got whatever information we could about the strength of Bks. and arms and that …

Q: How often would you meet them in that period?

A: On an average probably every two or three weeks … I did get very particular information about [sic – from] him because he told me candidly about the strength of Leopold Bks. He told me also of Smithfield Bks. In fact any information I wanted.”13

By March 1924, McGuinness was a Captain in the Defence Forces’ Office of Border Intelligence; he wrote to the Director of Intelligence stating that he had certain records relating to the 3rd Northern Division:

“… they contain an interesting and fairly exhaustive history of the pogrom in Belfast from 1920 up to the end of 1922. I can vouch for the reliability of the matter contained therein as I personally compiled them during my period as I.O. of the Division. I am having copies of all such in my possession typed, and will forward them to you each day until completed.”14

The 20 files which McGuinness had typed up are now part of the Historical Section Collection in Military Archives. There is some duplication between them and the 16 files of the Séamus Woods Collection within the Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents, also in Military Archives, the list of which almost exactly corresponds to the list of 14 files that the RUC discovered to have been stolen from Solly-Flood’s office – Woods had two additional files which the RUC overlooked.15

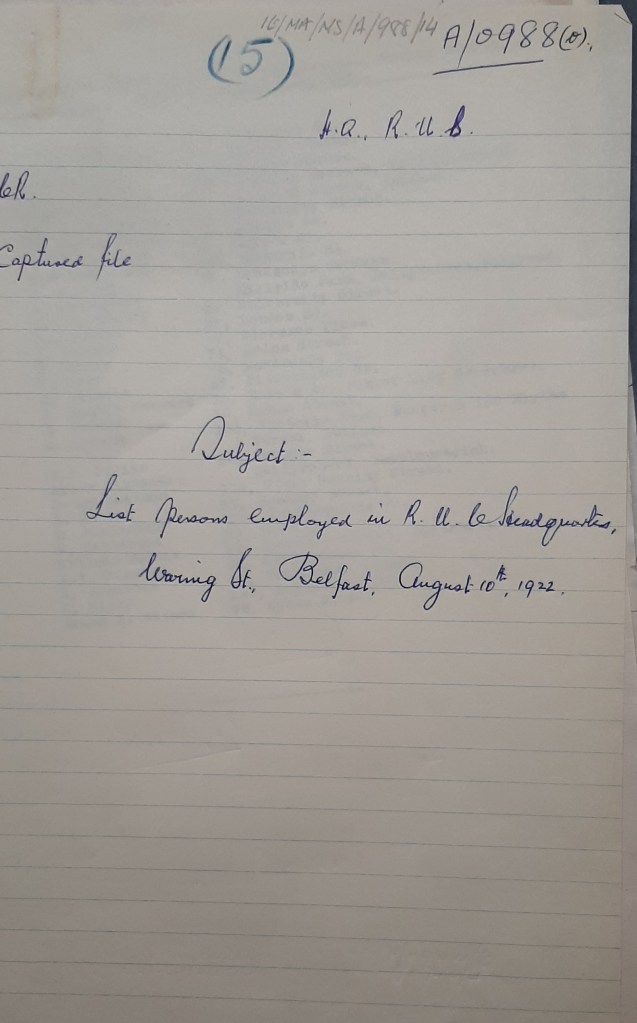

However, some of the files that McGuinness got typed up were unique and not duplicated. One sounds relatively innocuous: “List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th, 1922.” But this file also contains a startling document, dated July 1922, headed: “List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes.” This consists of a list of 648 named individuals, for whom addresses are also given for all but 13; for 63 of those named, only the barracks in which they were stationed is given, but for the other 572, their home addresses are shown.16

The origin of this document can now be seen: it is most likely a composite, with the home addresses taken from whatever personnel records Stapleton was able to “borrow” from RUC Headquarters and have transcribed; this was then supplemented by additional information supplied by the network of sympathetic policemen at the various barracks around Belfast, who might not have had access to such detail as their colleagues’ home addresses, particularly if those colleagues were Protestants and the regular policemen were Catholics.

Having compiled the composite list, the IRA’s Intelligence Department then added details relating to some individuals under a heading, “Particulars.” We will return to this point later.

Cover sheet of “List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th, 1922” IE/MA/HS/A/0988/15 (image used with kind permission of Military Archives)

In order to increase the overall sample size, the names (and addresses where available) of 12 other Specials charged with firearms offences in the Belfast courts were added, as well as similar information for 17 Specials killed either on- or off-duty during the Pogrom. This gives a total sample of 677 men.

What can be learned from this sample?

Which classes of Specials were they?

The first thing to be said is that there were massive gaps in the IRA’s intelligence – 648, or even 677, Specials was only a small portion of the overall number of Specials in Belfast, which would have been counted in thousands rather than in hundreds.

While there were 26 RUC barracks in Belfast at the time, only ten of those were used to provide a barracks-only address for men in the sample. Two of the missing barracks in particular stand out, as we know from other sources that Sergeants in both Musgrave St and Henry St Barracks were sympathetic to the IRA; these policemen could conceivably have provided the names of Specials attached to those barracks.17

Similarly, while it was noted that some men were assigned to Specials outposts at City Hall or the Beehive Bar on the Falls Road, there was no mention of other outposts such as the one at the Falls Road Library.

Specials outpost at the Falls Road Library

Although there were three classes of Special Constabulary, the vast majority of men named in the IRA document were B Specials: 573, or 88%. An additional 45, or 7% were noted as being A Specials. Only two men in the document were C Specials, which is disappointing as this was the most numerous of the three classes – this is another notable weakness of the document, although it may also reflect poor record-keeping for the C Specials within the RUC. Expanding the sample made no material difference to these figures, other than adding a handful of C Specials.

Fourteen of the men had no Special Constabulary class noted, but did have a police rank; this group includes recognisable members of the regular RUC such as County Inspector Richard Harrison and District Inspector John Nixon, as well as detectives, so it is assumed that all of these were regular police.

A further 14 had neither a Special Constabulary class nor a police rank noted – this may have been an oversight on the part of whoever typed the list, or it may be that their names were included by virtue of the entries against them under “Particulars.” In place of a Special Constabulary class, one man was simply noted as being in the UVF.

Where did they live?

No home addresses were available for 89 of the names in the wider sample – no address at all was given for 23 and for the remaining 66, the only address given was the barracks to which they were assigned.

For the 588 whose home addresses are available, an interesting geographical spread can be seen:

- West 189

- North 142

- South 93

- East 42

- Centre 26

- Hinterland 97

“Hinterland” here refers to towns a short distance outside Belfast, such as Lisburn and Newtownabbey in Antrim, or Holywood and Bangor in Down. Nowadays, they might be considered suburbs of Belfast but in the 1920s, they were distinct entities lying beyond the city boundaries. The men living in these areas may have been assigned to their local barracks or they may have been stationed at barracks in the city, travelling in by train or tram.

Further surprises await when we go into more detail for each part of the city.

In west Belfast, the district that contributed the most Specials was not the Shankill or Woodvale, as one might expect, but the Grosvenor Road area, particularly the network of streets around the top of Roden St, west of the railway line and facing the Lower Falls. There were 59 Specials from the Grosvenor Road as opposed to 49 from the Shankill and a further 24 from streets such as Cupar St in what could be termed the Falls-Shankill interface. Woodvale contributed a mere six.

Stanley St off the Grosvenor Road (PRONI, Belfast Corporation Archive, Hogg Collection, LA/7/8/HF)

A possible explanation for the relatively low numbers of B Specials from the Shankill and Woodvale lies in the emergence of the Imperial Guards. After its series of church parades on 13th November 1921, the following day’s newspapers reported that the “largest attendance” was that of the West Division, four battalions of which marched to Townsend St Presbyterian Church. As noted above, in the spring of 1922, the Imperial Guards, as well as other paramilitary groups, were incorporated into the Special Constabulary as a new C1 class. Therefore, while these areas of loyalist west Belfast were under-represented in the B Specials, they may have been over-represented in the C1 Specials, who do not feature in the IRA document.18

In a reminder of how much religious segregation in Belfast has changed since the 1920s, 19 Specials came from the area at the junction of Broadway and the Falls Road – in fact, all but two of them lived in just two streets: Braemar St and Thames St. However, it should be remembered that until 1982, the building that is now the Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich on the Falls Road housed the Broadway Presbyterian Church – these men would have been among the congregation served by that church.

Broadway Presbyterian Church on the Falls Road

There were also Specials living in what would today be considered other nationalist strongholds – five in the Lower Falls, four in Andersonstown and two each in Clonard and Beechmount.

In north Belfast, the areas around North Queen St, York St and the docks were the most violent, with over a fifth of all the city’s Pogrom fatalities occurring there. However, recruitment to the Specials was relatively light in Sailortown (23), the York Road (eight) and North Queen St (seven).

In contrast, there was a higher concentration in Oldpark: 39 Specials lived either on the Oldpark Road itself or the streets adjoining it, in particular the “Bally-” streets named after towns in Antrim such as Ballycastle and Ballyclare – these streets faced the small nationalist Marrowbone or ‘Bone enclave; a further 15 lived in Ardoyne or the ‘Bone itself.

There were almost twice as many Specials in the New Lodge as there were in Tiger’s Bay – 23 versus 12.

South Belfast is another part of the city that both confounds pre-conceptions and further illustrates changing demographics. The highest numbers of Specials here were not from Sandy Row, the Village or Donegall Pass, which only had seven, five and four respectively. Rather, they were mainly from Ballynafeigh, between the Ormeau Road and the River Lagan – 39 lived here. A further 24 lived in what is now another majority-nationalist area, the Lower Ormeau.

Ormeau Road in Ballynafeigh

Although the figure of 42 Specials from east Belfast may appear to be surprisingly low, it should be noted that almost half of the 66 men for whom only a barracks address was given were noted as being assigned to Mountpottinger Barracks in Ballymacarrett; most, if not all, of these probably lived in east Belfast.

Half of the east Belfast Specials whose home addresses are known lived in Ballymacarrett – 22 out of the 42. The remainder mostly lived near the main arterial roads leading out from there – the Woodstock, Castlereagh and Ravenhill Roads.

Six hundred men paraded with the East Battalion of the Imperial Guards in November 1921.19 As noted above in relation to the Shankill and Woodvale, involvement with the Imperial Guards may also have steered east Belfast men towards the C1 rather than the B Specials. However, there was a third pole of attraction for those who wanted to shoot Catholics: the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA) was another loyalist paramilitary organisation which was particularly strong in the east of the city. For some, the Specials and UPA did not represent an either-or choice – it could be both: Robert Craig from Convention St is noted in the IRA document as being a B Special, but he was also described by the RUC as being the chairman of the UPA; Craig was eventually interned in November 1922.20

The same RUC file contains a very telling memo to the Northern Ireland cabinet from Wilfrid Spender, the Cabinet Secretary – referring to the internment of loyalist gunmen, he said:

“Four of these were in the C1 Special Constabulary but the I.G. [Inspector-General of the RUC] does not know whether they are still members of that force. The matter is being treated with secrecy as the I.G. does not wish to initiate inquiries on this point.”21

This tells us two things: first, that record-keeping for the C1 Specials was so haphazard that even the RUC did not know who was or was not a member, and second, that the authorities knew that the Special Constabulary barrel contained at least some rotten apples but they had no desire to find out exactly how many.

C1 Specials on Albertbridge Road in east Belfast

What ages were the Specials?

In his 2020 book, Political Conflict in East Ulster 1920-22 – Revolution and Reprisal, historian Christopher Magill presented the results of his research on the application forms of a sample of 1,192 B Specials from Down: he showed their ages, how many of them were too young to have been in the pre-war UVF and how many had prior military experience.22

Although the 1922 IRA document did not include details of the men’s ages, a similar analysis can be attempted by referring to the 1911 Census. However, cross-referencing the men named in the document with the Census is extremely difficult. This is partly because migration to Belfast in search of work continued in the years after the Census. But more significantly, most accommodation in Belfast at the time was rented and so families tended to move regularly, although often staying within a particular area.

As an illustration, my own great-grandparents went through such a process. In 1915, they moved from Lavinia St in the Lower Ormeau to Whitehall Gardens in Ballynafeigh. In 1921, as was not uncommon during the Pogrom, they did a house swap with a Protestant family, leaving this area where so many of their neighbours joined the B Specials and moving to the top of the Donegall Road beyond Broadway. Three years later, they moved again – to a house that was next door to the house they had previously moved into. Thereafter, the Glennons stayed put – when my great-grandmother died in 1957, my grandfather took over the tenancy and he continued living there until his death in 1967.23

Out of the total sample of Specials, the ages of slightly under half – 318, or 47% – could be identified with varying levels of certainty.

Of those, 26 names could be matched exactly, down to the same house number in the same street in both the Census and the IRA document. A further 79 could be matched to the same street, but a different house number – this could be because the IRA’s intelligence was imperfect or because, like my great-grandparents, they had moved house in the interim.

Another 157 could be found living in the same area, but a different street. To give an example: in 1922, B Special Albert Nicholson was noted by the IRA as living at “Adlington St” – there was no such street in Belfast at that time, but there was an Edlingham St in Tiger’s Bay; in the Census, Albert Nicholson was a 13-year-old boy living in Ruth St, which was a side-street off Edlingham St. Here, they are assumed to be one and the same Albert Nicholson.

The same assumption can be made in relation to men who had very distinctive, or even unique names. For example, Victor Porter, aged 13, of Tullyniskane in Tyrone was the only person by that name in the entire Census – he is therefore assumed to be the same B Special Victor Porter who the IRA had listed as living in Ballyclare St in Oldpark. He may have come to Belfast after 1911 looking for work, but why he moved is less relevant than the fact that there was only one Victor Porter in the whole of Ireland. From the sample, 41 men had similarly distinctive names.

Among the 17 Specials killed during the Pogrom, the ages of all but one were given in the newspaper reports of their deaths or inquests, so there was no need to consult the Census in their cases.24

On this basis, the ages in 1922 of the 318 men identified were as follows:

- 16-19 22 7%

- 20-29 146 46%

- 30-39 89 28%

- 40-49 48 15%

- 50 or over 13 4%

This allows a popular misconception about the Specials to be challenged: they were not simply the pre-war UVF given police uniforms. If we dial the men’s ages back to 1914, and assume a minimum age requirement of 17 for membership of the UVF, then 97 men or 31% of the sample whose ages are known – almost a third – were not old enough at that stage to have been UVF members.

Almost a third of the sample were too young to have been in the pre-war UVF

If we then move the age dial forward to 1918, and make the same assumption of a minimum age requirement of 17 for enlistment in the British Army, then 262 or 82% of the sample whose ages are known were in the right age bracket to have had wartime military service. Not all of these were necessarily ex-servicemen – the IRA document does not specify who did or didn’t join up.

Various historians have provided estimates of wartime recruiting in the north which provide a guide to how many of the sample may actually have enlisted. Timothy Bowman states that roughly a third of the pre-War UVF enlisted, though not all necessarily in the 36th Ulster Division; this would equate to 88 men from those Specials whose ages are known.25

However, in a more detailed study focussing on west Belfast, Richard Grayson says:

“… men between 18 and 40 were around 17 per cent of the population of the city as a whole, which would mean approximately 20,060 of that age range in West Belfast. If we assume that most recruits were in this age range, then records have been found for about 44 per cent of them, and the figure may be nearer 60 per cent.”26

36th Ulster Division departing from Belfast

Applying Grayson’s percentages to the portion of the sample who were eligible for military service then gives a figure of between 115 and 157 men.

In 1918, 35 or 11% of the men were still too young to have been British soldiers. By the same token, 21 or 7% of them were unlikely to have had wartime military service as they were aged over 41 in 1918 – this was the maximum age for conscription under the Military Service Act 1916; although that Act was not applied in Ireland, it provides a useful indication of the upper age limit for recruits that the British Army was willing to accept.27

So out of 318 Specials whose ages are known, the highest estimate is that 157 of them – roughly half – may have been ex-servicemen.

“Particulars”

The IRA document included a final column headed “Particulars,” which contained a variety of personal information on some, but not all, of the Specials – 136 of the 648.

This could range from a simple physical description – one man was “Tall, well made. P.[protruding?] nose, B.[brown/black/bushy?] moustache, red face” – to a statement about where they worked.

Four of the Specials were noted as being “RC” – this was obviously an abbreviation for “Roman Catholic”; a fifth man was found to be a Catholic in the Census. While clearly only a tiny proportion of the total, this shows that the Specials were not an exclusively Protestant force. In fact, a Catholic Special, John Melaugh, was shot and wounded on 4th December 1920 while making his way home to Chatham St in Ardoyne.28

Bizarrely, B Special John Phillips from the Springfield Road was described as an “Ex-goalkeeper,” although it is possible to surmise a potential source for this snippet. Michael Brennan from Carrick Hill was the captain of the Alton United football team from that area which won the 1923 FAI Cup Final; his brother Robert was on the committee of the club but was also the Captain of the local IRA company – it is possible that he knew Phillips through football and passed on the information regarding Phillips’ sporting past.29

But some of the details given under “Particulars” were more sinister.

Seven of the men on the list were stated to be former members of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC; two of these were found in the Census, so the other five may have been British ex-Auxiliaries who moved to Belfast after being disbanded.30

Four more were named as former Black and Tans, of whom three were found in the Census, further undermining the misconception that the Black and Tans were simply imported into Ireland from Britain. Among these, “Jim Blackbourne” from Carrickfergus was actually James Blackburne, a former Auxiliary rather than a Black and Tan.31

Several men had been members of the Auxiliaries or Black and Tans prior to joining the Specials

Three were stated to be “Bad” or “Very bad”, while a further 15 were dubbed “Suspect” – this meant that the IRA thought they were involved in illicit activities carried out by the police. For example, one such “Suspect”, B Special J.A. Porter from Ballycarry St in Oldpark, is undoubtedly the John A. Porter who was tried but acquitted of the “Murder of Michael Crudden (Catholic) during sectarian trouble in the Oldpark Road area of Belfast” on 13th December 1921.32

B Special Smyth from Rosetta at the end of the Ormeau Road was “suspected of being at the shooting of Duffins,” while against B Special Starrett, the document stated, “Brother in GNR [Great Northern Railway] says he took part in the Duffin murders,” both references being to two brothers killed by the RIC “murder gang” in April 1921.33

The document also identified six other known members of the “murder gang”: County Inspector Harrison, District Inspector Nixon, Sergeant Hicks and Constable Hare of the regular police and Special Constables Giff and Norris.

The connections between the Specials and wider loyalist violence were also highlighted: eight B Specials on the list – four of them from Thames St near Broadway – were each described as “Mobsman,” while B Specials Casson and Gordon, both from Hillman St in the New Lodge, were each described as “Mob leader.”

One A Special and four B Specials were stated to have carried out burnings or evictions in particular streets. B Special Matchett of Corporation St was believed to be a bomb-maker, while three others were suspected of having carried out bombing attacks. Two A Specials and five B Specials were alleged to have shot and wounded specified individuals, including one British soldier; four other B Specials were described as snipers.

Responsibility for particular killings was attributed to individuals: B Special Sandy Pritchard from Ballymacarrett was stated to have “Shot Mrs Donnelly dead” – she was a Catholic woman killed in her shop on the Castlereagh Road on 17th December 1921. B Special Hookey Walker allegedly “Murdered Mrs Lynch, Letitia St, 5-3-22.” Perhaps even more striking was that B Special John Martin from the Lower Ormeau apparently “Confessed to murder of Reilly, Marrowbone” – Thomas Reilly was shot dead in Brookfield St in Ardoyne on 25th May 1921. None of these three Specials were charged with the respective killings.

Overlaps in terms of dual membership of both the Specials and non-state loyalist paramilitaries were also shown: the abbreviation “IG” (for Imperial Guards) was next to five B Specials, including brothers Sam and William McClurg from the Lower Ormeau and William McMaster from the Lisburn Road, who was stated to be a “Comdt.”

However, there were gaps in the IRA’s intelligence: B Special Edward Mayes, also from the Lower Ormeau, had been reported in the press as being the Commandant of the South Belfast Imperial Guards at their November 1921 church parade; his membership of the Imperial Guards was not noted.34

Paying more attention to press reports would also have alerted the IRA to A Special Barnsley Sloan’s membership of the Imperial Guards: he, along with two other members, had provided an alibi for James Galbraith who was prosecuted for attempted murder – they testified that on the day in question, Galbraith had been with them at the funeral of an Imperial Guard. The press report mentioned Sloan’s membership of the Imperial Guards though not his membership of the Specials.35

York St Battalion of the Imperial Guards at the funeral of one of their members (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 18th March 1922)

David Duncan’s Special Constabulary class was not stated in the document, but he was still of keen interest to the IRA: “Ex-B&T and lives with H. Black, York Street, Adj.[Adjutant] in Imp. Gds.” Here, the IRA’s intelligence was slightly faulty – Duncan was not actually a former Black and Tan, but had been an Auxiliary, before being fined by his company commander, then suspended, after which his services were “dispensed with.” He was another one of only 12 people to be charged with murder during the entire Pogrom – in January 1922, he had gone on trial for “shooting at Patrick McMahon and murdering James McIvor during sectarian trouble in Little Patrick St.” He was acquited of both charges and later sued the Freeman’s Journal for stating that he had also been implicated in a bomb attack on a Catholic-owned grocery shop in York St in July 1922.36

Summary and conclusions

The IRA document does not purport to be a comprehensive list of the membership of the Special Constabulary in Belfast – indeed, it is difficult to imagine how they could have even gone about compiling such an equivalent to the MSPC’s nominal rolls.

There were holes in the IRA’s information, most notably the almost complete absence of intelligence relating to the C Specials. Another major flaw was the fact that no barracks-only address was provided in relation to men stationed at over half of the RUC’s barracks.

Additional information could have been gathered from press reports and there are various Specials named in the statements given to a Provisional Government investigator in March 1922 who do not feature in the list; assuming the IRA also had access to those statements, cross-referencing the two should have been straightforward.

Other discrepancies are more forgivable, for example, the confusing of ex-Auxiliaries with former Black and Tans and vice-versa; similarly, the infamous Alex “Buck Alec” Robinson is named as a B Special although he was in fact a C1 Special.37

Taking these deficiencies into account, the document should be viewed as a summary of what the IRA believed they knew about almost 650 men, an admittedly small proportion of the city’s Specials. Few intelligence reports – gathered by either the IRA or the police – were likely to be 100% complete or 100% accurate, but their contents still provide useful material for analysis.

The most surprising discovery relates to where the Specials came from – or more particularly, where they did not come from. Traditional strongholds of muscular working-class loyalism, such as the Shankill or Sandy Row, were not necessarily the main sources of Specials – instead, it was areas on slightly higher social rungs such as Ballynafeigh or Oldpark that were more fertile recruiting grounds. But this conclusion needs to be tempered by the parallel development of loyalist paramilitary organisations like the Imperial Guards and UPA in the period leading up to the document’s creation.

Relatively high numbers of Specials in 1922 lived in areas that would have been improbable more recently – the Broadway stretch of the Falls, or the New Lodge and the Lower Ormeau. The fact that they were still living there in mid-1922 after the most serious Pogrom-related population displacements only serves to highlight the demographic shifts that Belfast has undergone since.

The age-related information that can be gleaned from the Census is also important. While the resurrection of the UVF was an important early step in the process that led to the formation of the Specials, the UVF was not the only well from which the Specials drew recruits – almost a third of them were too young to have been in the pre-war UVF.

Similarly, while it is only possible to estimate how many Specials may have been ex-servicemen, the fact that just half of them fall under this heading suggests that the Specials as a whole were not simply battle-hardened veterans of the Great War. Some were, some were not, but further research is needed to understand how many of the total pool of returning ex-servicemen, both Protestant and Catholic, had heard enough gunfire by 1920 to last a lifetime and had no wish to contribute more.

The information captured under “Particulars” provides useful insights into the conduct of the Specials.

Not all were violent sectarian thugs but all did want to defend Northern Ireland against the threat that they felt republicanism represented – being a Special offered an active way of doing so. A dozen in the document had experience of doing so brutally, through their previous membership of the Auxiliaries or Black and Tans prior to the Treaty.

There were clear overlaps with loyalist paramilitary groups in terms of dual membership, with another 13 Specials either noted in the document as also being, or now known to have also been, members of the UVF, Imperial Guards or UPA.

While all Specials wanted to defend Northern Ireland, it was how some Specials were prepared to go about that which created the cloud that hung over the force for the duration of its existence – some clearly had no qualms about crossing the boundaries of legality. Even ignoring those Specials who the IRA felt were merely “Bad” or “Suspect” or a general “Mobsman” without being able to attribute particular attacks to them, a litany of Specials named in the document were stated to have participated in a range of specific attacks on Catholics, including burnings, evictions, bombings, non-fatal shootings and even killings of civilians. Others were named as being participants in the activities of the police “murder gang.”

It is little wonder that the most damning assessment of the Specials was probably that delivered a year before the IRA document was compiled: at the inquest into the death from machine-gun fire of a 13-year-old girl, Mary McGeown, on 13th July 1921, the inquest jury added a unique rider to its own verdict: “In the interests of peace, Special Constabulary should not be allowed into localities of people of opposite denominations.”38

References

1 Arthur Hezlet, The ‘B’ Specials – A History of the Ulster Special Constabulary (London, Pan Books, 1973), p11.

2 Diary entry for 27th July 1920, Diary about riots and disturbances and other events in 1920 to 1923, Private papers of Colonel F.H. Crawford, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), D640/11/1.

3 Belfast News-Letter, 13th July 1920; Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983) p24.

4 Ibid, p30 & p32.

5 Belfast News-Letter, 17th November 1921.

6 Diary entry for 27th October 1921, Diary about riots and disturbances, Crawford Papers, PRONI, D640/11/1.

7 Divisional Commissioner to Commissioners, County Inspectors & County Commandants, Secret, 9th November 1921, Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archive, P7/A/29.

8 Farrell, Arming the Protestants, p84.

9 Ibid, p95 & p111.

10 David McGuinness statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives (MA), WS417.

11 Ibid.

12 Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, one of the Military Adviser’s staff, PRONI, HA/32/1/271.

13 Desmond Crean file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), MA, MSP34REF4970.

14 Capt. David McGuinness to Director of Intelligence, 29th March 1924, Records of 3rd Northern Division, Historical Section Collection (HSC), MA, HS/A/0988/05.

15 McGuinness files: HSC, MA, HS/A/0988 series; Woods files: BMH Contemporary Documents, MA, BMH-CD-310; RUC list of stolen files: Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, PRONI, HA/32/1/271; a fifteenth file was listed but had a line drawn through it so I have assumed it was not missing after all.

16 List of Specials, ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ Classes, July 1922, in List of persons employed in RUC Headquarters, Waring St, August 10th 1922, HSC, MA, HS/A/0988/15. To avoid repetition, further references to this document will not be individually footnoted.

17 Sergeant McKeon in Musgrave St Barracks was named as a source of both weapons and warnings (see Henry Crofton file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF106). While Sergeant John Bruin of Henry St Barracks gave a statement to a Provisional Government investigator on 23rd March 1922 (see Northern Ireland outrages, National Archives of Ireland, TSCH/3/S11195), he was killed a month later – see Richard Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922 (Cork, Mercier Press, 2019), p 365.

18 Northern Whig, Belfast Telegraph, 14th November 1921.

19 Belfast Telegraph, 14th November 1921.

20 Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289.

21 Ibid.

22 Chrisopher Magill, Political Conflict in East Ulster 1920-22 – Revolution and Reprisal (Woodbridge, Boydell Press, 2020), p88-94.

23 Belfast Street Directories, 1915, 1920, 1921-22 & 1924, National Library of Ireland.

24 No age was stated for Special Constable William Campbell, who eventually died in 1924 at his home in Ahogill in Antrim from wounds sustained in an IRA attack in May 1922; there were 99 William Campbells aged 7 or over from rural parts of Antrim in the 1911 Census, which made pinpointing him in the Census impossible.

25 Timothy Bowman, Carson’s Army – the Ulster Volunteer Force 1920-22 (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007, p172-173.

26 Richard S. Grayson, Belfast Boys – How Unionists and Nationalists Fought and Died Together in the First World War (London, Continuum Books, 2010), p194.

27 A second Military Service Act was passed in April 1918, after the British Army had suffered severe casualties due to the German spring offensive – this raised the upper age limit for conscription to 51. This Act was not applied to Ireland either.

28 Belfast News-Letter, 6th December 1920.

29 Robert James Brennan file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF25799; “Football trophy finally crosses border a century after Belfast side’s triumph,” Irish News, 28th September 2023. This paragraph was updated on 31st December 2023 with information kindly supplied by Siobhan Deane, Michael Brennan’s granddaughter.

30 It should be noted that the IRA’s intelligence was not necessarily 100% correct: of the seven men it named as former Auxiliaries, only one could be matched exactly with an individual named on www.theauxiliaries.com, three others were possible matches and the other three could not be found at all – they may actually have been former Black and Tans. One of the possible matches was named as “McGonigal” in the IRA document – this may refer to David McMonagle, originally from Derry, who was wounded in an IRA attack on an Auxiliary patrol at Dillon’s Cross in Cork on 11th December 1920, an attack which led to the burning of Cork as a reprisal by the Auxiliaries: https://www.theauxiliaries.com/men-alphabetical/men-m/mcmonagle-dbc/mcmonagle.html Although not named in the IRA document, Special Sergeant Alfred McMahon, wounded in a gun-battle with the IRA in Joy St in the Market on 13th April 1922, was also a former Auxiliary: Northern Whig, 21st November 1922; https://www.theauxiliaries.com/men-alphabetical/men-m/mcmahon-an/an-mcmahon.html

31 https://www.theauxiliaries.com/men-alphabetical/men-b/blackburne-j/blackburne.html

32 John A. Porter – murder of Michael Crudden during sectarian trouble in the Oldpark Road area of Belfast, Crown Files, Assizes and Commission, PRONI, BELF/1/1/2/67/7; Northern Whig 17th December 1921, Belfast News-Letter 22nd February 1922.

33 Irish News, 26th April 1921.

34 Northern Whig, 14th November 1921.

35 Northern Whig, 21st February 1922.

36 https://www.theauxiliaries.com/men-alphabetical/men-d/duncan-d/duncan.html; Crown Files, Assizes and Commission, PRONI, BELF/1/1/2/67/8; Belfast News-Letter, 4th November 1922.

37 Sean O’Connell, ‘Violence and Social Memory in Twentieth-Century Belfast: Stories of Buck Alec Robinson’, in Journal of British Studies, Volume 53, Issue 3, (July 2014) p734–756.

38 Belfast Telegraph, 18th August 1921.

Leave a comment