From the start of the Pogrom in July 1920 until the end of 1922, there were almost 350 prosecutions in courts in Belfast, under different pieces of legislation, for various firearms offences ranging from simple possession to murder. At one point, there was a public complaint that the courts were being “Outstanding in their leniency” in how they treated defendants. Who were these defendants, what verdicts were returned and what do their cases tell us about the operation of the judicial system in Belfast during this period?

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

The law and the courts

Until the early spring of 1922, the main legal provision used to charge people for being in unlawful possession of firearms was that the weapons were “not under effective military control.” This charge flowed from the Defence of the Realm Acts of 1914 and 1915 (DORA), which allowed the British government to introduce a wide variety of regulations limiting many aspects of life during the Great War – Regulation 33 stated that “No person, without the written permission of the competent … military authority, shall … be in possession … of any firearms or ammunition.”1

DORA Regulations remained in force after the end of the War. In August 1920, faced with insurrection in Ireland, the UK Parliament passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act (ROIA); the most notable provisions of this legislation were that additional DORA regulations could be issued that would apply only in Ireland, that courts-martial could also try cases and inflict punishments including the death penalty for certain offences and that military courts of inquiry could replace coroners and their juries.2

Then in mid-February 1922, a government notice headed “Firearms Act 1920” was inserted in the press:

“All persons are hereby required to take notice that the above Act is now in force in Northern Ireland. By this Act every person (unless he holds a Firearms Certificate from the County Inspector of R.I.C. of the County in which such Person resides) IS PROHIBITED from having in his Possession, Using, Carrying, Buying, Selling, Repairing, Testing, Taking in Pawn or otherwise Dealing with ANY FIREARM OR AMMUNITION Under a Penalty of Two Years’ Imprisonment with Hard Labour.”3

The final piece of legislation was the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act, introduced by the Unionist Government of Northern Ireland in April 1922. This allowed the Minister for Home Affairs to create similar regulations to those provided for under the DORA and ROIA. Section 5 of the Act allowed for the imposition of flogging as an additional punishment to imprisonment for offences under the Firearms Act 1920 or for arson, while the Schedule of the Act said, “The civil authority [meaning the Minister] may make orders prohibiting or restricting in any area … (d) The carrying, having or keeping of firearms, military arms, ammunition or explosive substances.”4

However, possession of firearms was one thing – using them was a far more serious matter and of course, murder and attempted murder were already crimes on the statute books. As a result of the Pogrom, 502 people died in Belfast and over two thousand were wounded. British troops acknowledged at coroners’ inquests that they had been responsible for 51 of those killings; similarly, the police and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC or “Specials”) killed a further 21 people during rioting, for curfew violations or in confronting the IRA or loyalist paramilitaries. Deducting both of these, which were legally sanctioned as being carried out by arms of the state in the course of their duties, leaves 430 other killings.

Finally, as the IRA – and, presumably, corresponding organisations on the loyalist side – carried out armed robberies to raise funds, prosecutions for such offences are also included in the analysis.

People charged with any of these laws, which are gathered here under the umbrella term “firearms offences,” could appear in a variety of courts.

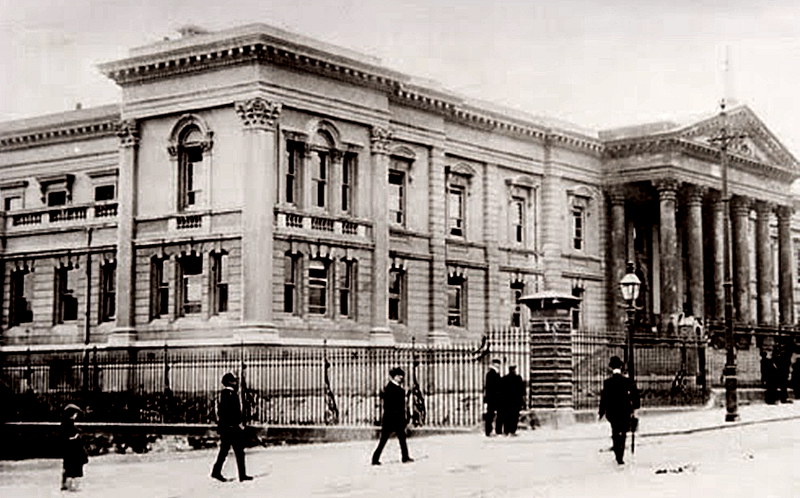

Crumlin Road Courthouse, where many of the cases were heard

The first port of call was usually the Belfast Custody Court, also known colloquially as the Belfast Police Court. Here, a magistrate sitting without a jury could impose a punishment if the defendant pleaded guilty or could remand the defendant to a sitting of the Courts of Petty Sessions. These also featured a magistrate sitting without a jury, who could reach a summary verdict.

For more serious offences, the Courts of Petty Sessions would also act as preliminary hearings for the Quarterly Sessions and also for the assizes – at the latter, a grand jury would decide whether there was sufficient evidence in a Bill of Indictment to proceed to a full trial, which would then be heard by a fully-qualified judge and a jury.5

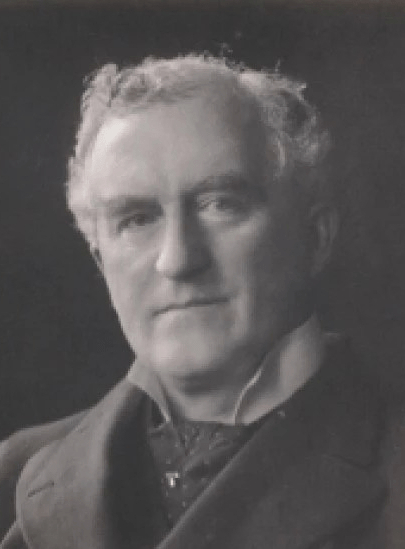

After the establishment of Northern Ireland in 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act, the assizes in Belfast were replaced by the Belfast City Commission. Cases here were often heard by Denis Henry, the first Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland – Henry was something of a “white blackbird,” in that he was a Catholic Unionist who later went on to become a cabinet minister.6

Denis Henry, first Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland

These various civil courts were supplemented by the courts-martial provided for by the ROIA, which continued to try cases in Belfast until at least October 1921. Court-martial hearings could be reported on in the press, while defendants were entitled to – but did not always avail of – legal representation in all courts, whether civil or military.

Analysis of the files held by the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland suggests that only a minority of the cases went all the way to being heard at the assizes or City Commission, involving 105 of the 344 cases that were reported in the press.7

The defendants

Those who appeared before the courts can be categorised under a number of headings.

In keeping with the principle of “innocent until proven guilty,” anyone who was acquitted or against whom the Crown entered a nolle prosequi (dropped the charges) is assumed to have been a civilian, unless it can be established from other sources that they were actually combatants.

Most of the IRA members tried can be found in the nominal rolls held in Military Archives’ Military Service Pensions Collection. However, there were a small number not listed in the nominal rolls who said in court that they were members of the IRA – as such a statement was hardly likely to improve their chances of acquittal, they are taken as being in the IRA.

Similarly, any defendant who said they were a member of the Specials is also taken at their word.

One defendant can definitely be identified as a member of Na Fianna in the nominal rolls. Another was almost certainly a Fianna member: 16-year-old Daniel O’Toole was convicted of having fired at Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Constable William Elliot twice at two locations within ten minutes of each other on 30th May 1922.8

A number of defendants refused to recognise the courts – this identifies them as being Republicans, without being able to specify whether they were IRA or Fianna members. A similar formulation backfired for an unnamed teenager who was charged with being in possession of a revolver and ammunition; the boy’s father had succeeded in persuading the court to allow him to provide bail for his son but,

“At this point the defendant – 15½ years of age – announced with a great flourish that as a soldier of the Irish Republic he could not accept bail. His father, with others, joined in the laughter that greeted this information. On account of the attitude he adopted the magistrates felt justified in sending him for a term to a reformatory.”9

A cyclist being searched in Belfast, February 1922

Where someone could not be identified as a member of the IRA, Fianna or Specials, their name and surname were checked in the 1911 Census and while someone’s religion is not a foolproof guide to their political persuasion, it is a useful indicator as to whether they were a nationalist or a loyalist. For example, everyone named William Stratton in the Census was Presbyterian, Methodist or a member of the Church of Ireland, so the William Stratton tried for possession of a revolver by a court-martial in February 1921 is assumed to be a loyalist.

Not all those thus identified as loyalists or nationalists were necessarily involved in the sectarian violence that gripped the city. Guns were plentiful in Belfast at the time so some people took the opportunity to commit armed robberies for motives that were more entrepreneurial than political.

In some instances, there were simply too many people of the same name but differing religions in the Census to be able to say with any certainty which side of the political divide they were on, so they are classed as unidentified.

With this in mind, the numbers of defendants were as follows:

- Civilians 89

- IRA 67

- Fianna 2

- Republicans 15

- Nationalists 63

- Specials 14

- Loyalists 82

- Unidentified 12

Three women were charged under the Firearms Act. A revolver and ammunition were found in the Herbert St home of Annie O’Neill in Ardoyne – she claimed they had been dropped by an unknown man who ran through the house. Minnie Patterson from Foreman St and Agnes Forsyth from Joseph St, both in the Shankill, were caught in possession of a disassembled rifle in Alfred St in the Market; although this suggests the possible existence of a loyalist counterpart to Cumann na mBan, they claimed they had simply been asked by a stranger to collect the rifle from a house in Sandy Row and bring it to the Shankill. Coincidentally, all three were arrested on the same day and they were also found guilty and sentenced on the same day – each was bound over, meaning they avoided custodial sentences.10

The relaxed demeanour of this man being searched in March 1922 suggests that he has nothing to hide

The charges – murder and attempted murder

Given that there were 430 killings other than those for which Crown forces had legal sanction, the most striking thing about prosecutions for murder is that there were so few of them – for these 430 killings, only 12 people were charged with murder.

As nationalists accounted for 57% of all fatalities of the Pogrom, it is of little surprise that these murder charges involved seven nationalist victims, one Special and three unionist civilians (two cases involved more than one defendant, while one man was charged with killing two women).

All 12 of those charged with murder were acquitted – these included one member of the IRA, one Special and two loyalist paramilitaries; by virtue of being found not guilty, the other eight are counted as civilians.

The common factor leading to acquitals was that some witnesses provided evidence of the defendant’s guilt, while others swore they were innocent.

A British army armoured car patrolling Foundry St, where Joseph McLeod was shot dead seven weeks later (Illustrated London News, 1st September 1920)

Henry McGraw was charged with the murder of Joseph McLeod during sectarian rioting in Foundry St in Ballymacarrett on 25th October 1920. The fatal shot was stated to have been fired from a nearby railway embankment – several witnesses, including a Special Constable, claimed to have seen McGraw firing from the embankment, some even said they recognised him, having known him by sight for years. But other witnesses stated that the Special was the ringleader of the loyalist rioters on the day in question and McGraw admitted that he had been involved in the riot but at no time did he go to the embankment. An RIC Constable even gave him something of an alibi: he said he had actually been speaking to McGraw about throwing stones – presumably, sternly – at the very moment McLeod was shot. McGraw, a member of B Company, 2nd Battalion of the IRA, was found not guilty.11

Eleven months later, on 24th September 1921, and only about a hundred yards away, Murtagh McAstocker, also a member of B Company, was shot dead on the Newtownards Road. When Thomas Pentland came to be prosecuted for his murder, there was conflicting evidence once more. Some witnesses said they had seen Pentland shooting McAstocker, while Pentland claimed he had actually gone to the wounded man’s assistance. The grand jury returned “no bill,” meaning they felt there was insufficient evidence to bring the case to a trial, so Pentland was discharged. The following year, he was interned on account of being the second-in-command of the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), a loyalist paramilitary organisation.12

The funeral of IRA member Murtagh McAstocker

The police had only slightly more success in prosecuting people for shooting at someone “with intent to murder” – the intended victim was even named in the vast majority of such charges. There were 54 people charged with this offence, but only 16 were found guilty.

Those found guilty included four members of the IRA, one of Na Fianna (Daniel O’Toole mentioned above), seven other nationalists and four loyalists. Those acquitted included a member of the IRA, a Special and two loyalist paramilitaries, the remainder being civilians.

Given that the intended victims were still alive to give testimony in court, it may be surprising that there were so many acquitals but again, evidence was inevitably contradictory, while there were often family members, friends or others from the same community willing to provide alibis, whether real or false.

Peter Cosgrove, along with Francis Corr, was initially charged with shooting at B Special Sergeant James McArthur while the latter was swimming at a dam in the Oldpark area on 25th May 1922. McArthur said that while Cosgrove had a revolver in his hand, it was Corr who had fired the three shots, so the charge against Cosgrove was reduced to aiding and abetting. Cosgrove’s employer then produced his time-clock punch card from the bakery where he worked, showing that Cosgrove had been in work at the time of the incident. The charges against Cosgrove, a member of A Company, 2nd Battalion of the IRA, were dropped. A month later, he was caught in possession of a revolver and this time, was found guilty.13

Joseph Arthurs was charged with “shooting at George Mitchell and Henry Burrows, soldiers of the 1st Battalion Somerset Regiment, in the grounds of St Matthew’s Roman Catholic church on the Newtownards Road” in June 1922; however, by the time the case came to the City Commission, this charge had been dropped and he was eventually found not guilty of possession of firearms. A few months later, Arthurs, who the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) described as “probably the worst gunman on the Newtownards Road,” was also interned as a member of the UPA.14

The charges – possession

The police had most success in court with charges of illegal possession of firearms, rather than murder or attempted murder. Of the 278 defendants charged with possession of weapons and/or ammunition, only 22% were acquitted, including 51 civilians, seven Specials and three members of the IRA. This includes those charged with armed robbery, as even if a weapon was not recovered by the police, its presence at the scene was implied.

A common reason for acquital was the inability of the police to prove that the defendants were actually in possession of the arms – this was the case with William Farrell and Patrick Bruce, next-door neighbours in Theodore St in the Lower Falls: a rifle was found on the wall separating their back-yards, but as there was an entry behind the yards, they were able to claim successfully that anyone could have left it there.15

The most unusual example of non-possession of arms involved Francis Teague from Slate St and Thomas Keenan from Quadrant St, both also in the Lower Falls: they were accused of using a revolver to commit armed robbery of a shop on St Patrick’s Day 1922. They were identified as the culprits by an eye-witness – she did so in a house where they were being questioned by the IRA’s Republican Police. The two miscreants were then handed over to the RIC – presumably, by being tied up and left to be found – but when the police arrived, the revolver had, of course, vanished. Confounded by this lack of evidence, the police had no choice but to drop the charges.16

Some defendants pleaded that they had simply found the firearm or ammunition in question, some even claimed to be bringing them to the police barracks when arrested. This became so commonplace that one exasperated magistrate exclaimed that he would no longer tolerate it as an excuse:

“Mr. Roche, R.M., said that it was a habit in such cases for the defence to state that the ammunition had been picked up in the street. In future the Bench would not listen to such defence; and if people saw ammunition in the street let them pass it.”17

Among the IRA members to avoid conviction was Charlie Connolly of C Company, 2nd Battalion. Despite initially declaring “I am not interested in the proceedings at all,” he was found not guilty of possessing empty shell cases, as his questioning of the RIC witness persuaded the jury that he had simply acquired the shells in the course of running his scrap-metal business.18

Charles McIlvenny was a member of the same company: charged with being in possession of a revolver in the course of an armed robbery (of a bicycle), the charge was dropped when the victim later proved unable or unwilling to identify him.19

Although an extensive IRA arms dump was found where he lived in Dunmore St in Clonard (more about which later), Patrick Doherty of B Company, 1st Battalion, was discharged as he was not the tenant of the house.20

Three off-duty B Specials, George Scott, Herbert Armstrong and David Brown, were arrested together for being in illegal possession of revolvers on the Grosvenor Road; shooting had been heard slightly earlier and there was no-one else around when the police arrived. When tried in court, they were discharged on the basis of having applied for permits, although Scott was dismissed from the Specials the day after being arrested.21

A C Special, George Pollock was found not guilty of illegal possession of revolvers by a jury; the charges against another, Robert Smith, were dropped, while a third, William Quinn, was also discharged on the basis that he had applied for a permit. In August 1922, a fourth C Special, William Nesbitt, was also acquited of possession of a revolver by a jury, but two months later, he was interned, as police suspected him of “being accountable for the deaths of at least 20 Catholics” going back as far as the previous February.22

A group of B Specials (Police Museum, Belfast)

However, the first person to be convicted under the Firearms Act was a B Special and he was arrested by other Specials. Joseph Morgan was stopped by a Specials patrol responding to a shooting incident off North Queen St on 14th February 1922 and was found to have a Martini carbine concealed under his coat, the barrel of which was still warm; the carbine was stamped “For God and Ulster,” which meant it was one of the consignment smuggled into Larne in 1912 for the Ulster Volunteer Force. Despite Morgan showing his B Special card to the patrol and him being an ex-soldier who had lost his leg at the Battle of Mons in 1914, he was charged, found guilty and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment.23

The sentences

Defendants who were found guilty faced a wide variety of sentences.

Eleven of those found guilty of attempted murder received sentences of a year’s imprisonment or less, the other five were sentenced to either three, six, ten or 15 years.

Two IRA members even had their sentences explicitly reduced by the trial judge: brothers Robert and William Carmichael of the IRA’s A Company, 2nd Battalion were convicted for shooting at shopkeeper William Douthart and unnamed others during rioting on the Oldpark Road in October 1920; when it came to sentencing, the judge said,

“…he sympathised with the prisoners in the provocation they received through their church being attacked … Had it not been for the extreme provocation they received he would have given them three years’ penal servitude, but under the circumstances he would only sentence them to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.”24

In the initial stages of the violence, in fact all the way up to the end of 1921, the various courts seemed to take a surprisingly relaxed view of firearms convictions: of the 52 people found guilty of possession, 12 were merely fined sums ranging from £2 to £10. Only 12 were sentenced to a year’s imprisonment or more.25

This relatively casual approach even extended to the courts-martial – in this period, they were responsible for half the convictions and also half the fines. Among those was Dominic Vella, fined £5 for having a revolver and ammunition in his home in Divis St; his barrister argued unsuccessfully for clemency, on the basis that Vella was blind – without explaining exactly what use a revolver was to a blind man.26

Such lax sentencing clearly disturbed the editor of the Belfast Telegraph, who complained:

“Crimes of this description are a menace to public safety, and will have to be sternly dealt with. Courts-martial have marked their sense of them by very heavy sentences, but the punishment meted out in some of the civil courts has been on a very different scale, and that does not at all coincide with the public view of the enormity of these offences. Some of the sentences passed in revolver cases at Belfast during the present year have been outstanding in their leniency.”27

Among the “heavy sentences” that were probably more to the Telegraph’s liking were those of 15 years’ imprisonment imposed on William Casey, Laurence Maguire and Patrick Begley, members of the IRA who were convicted of the attempted robbery of a £600 payroll on the Falls Road on 5th April 1921.28

An identical sentence was passed on Charlie Ryan, a member of B Company, 1st Battalion, for being one of a group of armed men who held up two military policemen in Donegall St and relieved them of their revolvers and ammunition on 10th April 1921; for good measure, he was also charged with throwing a bomb (hand-grenade) at a military post in Rosemary St. Ryan did not complete his sentence, being one of the IRA prisoners released under an amnesty after the signing of the Treaty in December 1921.29

Charlie Ryan (extreme right), celebrating his release from prison with Joe McKelvey (centre, in uniform) and other members of B Company (L to R): Seán O’Sullivan, Aloysius “Wish” Fox, Phillip Ryan (his brother) and unknown

From the start of 1922, as the violence intensified and the Firearms Act came into operation, there was a noticeable increase in both the number of prosecutions and the severity of sentencing.

For offences committed in the six months to the end of June, 101 people were found guilty, but only one was fined, 38 received prison terms of up to twelve months, while 30 got 18 months and 26 got even longer sentences of up to 5 years.30

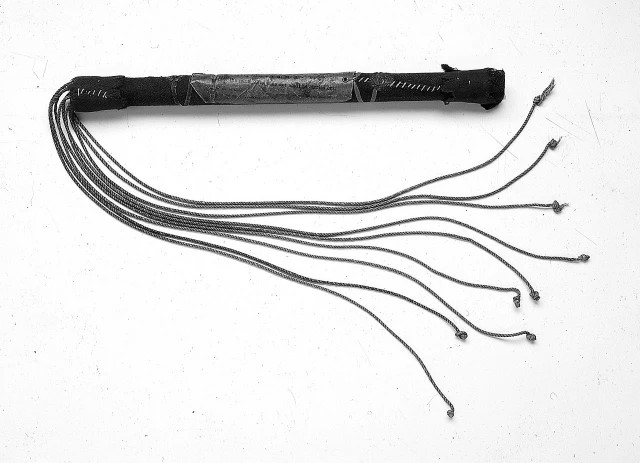

By the time some of these prisoners came to be sentenced, the Special Powers Act had been passed, so nine of them also had punishments of flogging imposed, including up to 15 lashes of the cat-o’-nine-tails or strokes of the birch. Flogging was not an alternative to a custodial sentence – it was not an either-or, it was as-well-as.

Under the Special Powers Act, defendants found guilty could be flogged with the cat-o’-nine-tails in addition to being imprisoned

The first person to be sentenced to flogging was David Wilson, who got four years’ imprisonment and 15 lashes of the “cat” for an armed robbery committed in Rosapenna St in Oldpark on 17th April 1922. Little is known of Wilson – he does not appear to have been a member of any combatant organisation and was described by the judge as “a reformatory boy” with three previous convictions for larceny.31

As the overall scale of the violence diminished, the number of prosecutions for firearms offences in the second half of 1922 was much reduced, with 50 people being convicted. However, sentencing remained punitive – 25 men got up to 12 months’ imprisonment, while the same number got longer sentences, the longest being seven years. Meanwhile, the application of flogging as an additional punishment intensified, with 21 of those convicted also being subjected to either the “cat” or the birch.

When we look at the even-handedness of sentencing, if anyone benefitted from the leniency that so exercised the Belfast Telegraph, it was the loyalists who made up the bulk of that paper’s readership.

In the period from July 1920 to December 1921, nine loyalists were fined while 13 received custodial sentences, only two of which were for a year or more; the comparable figures for IRA, Republicans and nationalists combined were two fined and 16 imprisoned, 12 of them for more than a year. All the IRA members convicted in that period received prison sentences, which is unsurprising given that they were engaged in armed rebellion.

The one Special jailed in the same period was another unusual case: Stanley Valentine stole six revolvers from Antrim Road RIC Barracks and sold them to a barman, Frank Dolan, who had approached him and promised him £5 for each revolver he could get. Valentine got six months in jail but the charge against Dolan of receiving the stolen revolvers was dropped.32

It would be a mistake to say that loyalists received “light sentences” but they were less likely to receive the harshest sentences: they accounted for 33% of all those convicted, but 26% of those sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment or more and just 20% of those flogged. Three Specials also received prison sentences of 12 or 18 months.33

However, one case suggests that magistrates were not afraid to make examples of loyalists. On 18th April 1922, the RIC discovered two rifles and 87 rounds of ammunition in a house belonging to Robert McCullagh in Disraeli St in Woodvale; while he was acquited on the basis that the arms didn’t belong to him, his two sons and seven other loyalists who were in the house at the time were each sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment.34

Sentencing of non-Republican nationalists was broadly in line with the 24% of overall convictions for which they accounted: they were 26% of those sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment or more and 27% of those flogged.

However, members of the IRA and Fianna were the most likely to receive harsh sentences, reflecting their attempt to overthrow the state: they represented 35% of those convicted but 39% of those sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment or more and 40% of those flogged.

The arms

There were 129 people caught red-handed with weapons and/or ammunition on them, or on people they were with, at the time they were arrested.

Of those, 19 were in possession of ammunition only. Thomas McFall was charged with being in possession of just a single bullet – his claim to have found it prompted the magistrate’s outburst mentioned earlier. Samuel Pike could hardly offer the same excuse – he was a C Special found to have 87 rounds of ammunition on him when searched on the York Road in July 1922.35

British military searching a motor-cycle for arms

On the other defendants, police and British troops found a total of six rifles, shotguns or carbines and 86 revolvers – the latter were obviously easier to conceal whereas the risk of being caught carrying long-barrelled weapons around was a deterrent to doing so. In addition, Charles McWhinney of the IRA was caught with a bomb on him in Union St in March 1922. A bomb was also found on a loyalist, Thomas Galway, in Carlow St in the Shankill; he was described in court as being “a man of weak mind,” so he received a two-month sentence while McWhinney refused to recognise the court and got two years.36

The authorities had more success finding weapons in the course of searching houses and other premises – a total of 68 rifles, 48 revolvers and 83 bombs were found this way. Arising from these searches, 103 people were charged – again, some instances involved more defendants than weapons, such as the incident in Disraeli St mentioned above.

Police conducting a search for arms in Library St in June 1922

In some instances, the quantities of arms found indicate that arms dumps had been discovered. In a disused stable off the Newtownards Road, a mixed search party of RIC and troops discovered what was called the “Clonallon St arsenal” – 6 rifles, 2 revolvers, 38 bombs, 3 rifle grenades, 605 rounds of ammunition, a Verey signalling pistol and various other military items. Two men, William Fitzsimons and Robert Waddell, whose houses had holes in the walls adjoining the stable, were charged, but the jury returned a curious verdict, stating that the pair “were guilty of knowing the stuff was there but not guilty of having it under their control.” Towards the end of 1922, Waddell became yet another member of the UPA to be interned.37

Also in east Belfast, loyalists were caught in the act of burying what was believed to be an arms dump belonging to the UPA. On 20th November 1922, police had staked out The Oval football ground in Dee St – there they caught three men in possession of 3 rifles, 8 bombs & 295 rounds of ammunition. Two, Thomas Waring and George Richards, were captured and charged, but a third man escaped. Richards told the police “I have nothing to say, only that Sterritt gave it to us” – this may have been a reference to a Constable Sterritt who was a member of the police “murder gang” led by District Inspector John Nixon and who was named as a participant in the McMahon family killings of March 1922.38

The largest single haul found by the police was in a house belonging to James Doherty in Dunville St in Clonard; there, they discovered 34 rifles, 12 revolvers, 30 bombs, 2 Verey pistols and several thousand rounds of ammunition. This had been the arms dump for B Company, 1st Battalion of the IRA since the previous year:

“His house was used as a dump for B Company for over one year, that is, from September 1921 … He [Doherty] volunteered to take these materials when danger threatened and as stated kept them in his own home. He looked after the arms by cleaning them but never had to move them from place to place. In consequence of this he was expected to remain at home and do guard duty continually. As a result he was exempted from other company duties.”39

Other arms dumps

As well as arms dumps in people’s houses, the police and military also captured arms dumps in derelict buildings. There were 16 such seizures reported, the largest being the discovery of 7 rifles, 6 revolvers, 5 bombs, ammunition, cordite and explosives in Alexander St West in the Lower Falls on 3rd July 1922.40

In fact, a string of IRA arms dumps were captured at the start of July 1922, which led the O/C of its 3rd Northern Division, Séamus Woods, to complain:

“Unfortunately, however, the anti-Irish element of the population are taking advantage of the situation, and are giving all possible information to the enemy. Several of our dumps have been captured within the last few weeks, and in practically every case the raiding party went direct to the house.”41

Within a week, apart from the dump in Alexander St West, others in Milan St and Osman St, both also in the Lower Falls, Ardilea St in the Marrowbone and Rathbone St in the Market were also captured.42

IRA arms dump in Milan St, captured on 29th June 1922

Altogether, discovery of such dumps meant the police captured an additional 25 rifles and 18 revolvers, as well as 38 loose bombs and seven full cases of bombs.

Summary and conclusions

The police and courts had a wide range of legislation relating to firearms offences at their disposal, beginning with the DORA and ROIA Regulations, later supplemented by the provisions of the Firearms Act and finally by the Special Powers Act.

In terms of their willingness to enforce this legislation, the RIC and later the RUC engaged in institutional double-think.

Some within these organisations were involved in perpetrating the very violence that they were later supposed to investigate – the Nixon “murder gang” being the most striking example. Policemen with nationalist sympathies made statements to a Provisional Government investigator, implicating several senior police officers in covering up killings and other firearms offences committed by men under their command, whether those were regular police or Specials. District Inspector Spears of Mountpottinger Barracks was one of those named in such a statement – yet he also led the stake-out at The Oval that uncovered the UPA arms dump.43

The temporary tolerance of the UPA and other loyalist paramilitaries also represented double-think, but at a political level. Thomas Pentland of the east Belfast UPA was charged with murder as far back as the autumn of 1921, while William Nesbitt was suspected of committing a murder in February 1922 and the “Clonallon St arsenal” was discovered in March. Internment was introduced in May but none of these loyalists were interned before the end of the following September – that gave them four months’ additional free rein to play their part in terrifying nationalists into quiescence. Only after that useful work had been completed did the Minister for Home Affairs, Richard Dawson Bates, start issuing internment orders against them.

But if DI Spears personified the Jekyll-and-Hyde approach, there were plenty of other police who diligently went about their duty, searching and arresting suspects for firearms offences, and doing so impartially. Specials and other loyalists accounted for a quarter of those charged and a third of those convicted, so it is clear that not all police turned a blind eye to their actions. The arrest of B Special Joseph Morgan by a patrol of other Specials, leading to his ultimate conviction and imprisonment, is a unique and isolated example, but it does suggest that not even all Specials were necessarily bent on depredation.44

While they did not lack legal powers, or the inclination to use them, what the police did lack in terms of securing convictions was evidence. This was particularly the case for the most serious charges of murder and attempted murder, where although the police thought they had the basis for pursuing a prosecution, the defence could, more often than not, provide enough exonerating evidence to secure an acquittal. Only where the proof seemed incontrovertible – when someone was physically caught with firearms on their person or in their home – would a conviction prove more likely, and even then, a skilled barrister might still secure a release.

On balance, the courts also appear to have applied the laws impartially when cases came before them – they were by no means the judicial wing of the Specials. The verdicts reached put paid to any notion that juries were inherently biased in one direction or the other.

There were identical numbers of IRA members and loyalist paramilitaries acquitted: five of each. Nine Specials were acquited, four of them because the permits for which they had applied had not yet been issued, also leaving five.

At the same time, there were more Republicans convicted (56 IRA, two Fianna and 14 unspecified) than Specials (a mere four), but this is to be expected as Republicans were at war with the state. There were more non-state loyalists convicted than non-Republican nationalists, 67 versus 48, but this is also to be expected as most of the violence was directed at nationalist civilians.

When it came to sentencing, the apparent readiness of the courts – even including the courts-martial – to simply shrug their judicial shoulders and merely impose a fine for possession of firearms is just staggering. This, however, was mainly in the earlier phase of the Pogrom, when the level of killings had not yet reached its peak. As the fatal violence escalated during the spring and early summer of 1922, the sentences imposed were much harsher and continued in that vein in the second half of that year, even after the worst of the violence had subsided.

The fact that Republicans were more likely to receive the harshest sentences – lengthy sentences of over a year’s imprisonment, with or without flogging – probably reflects the defendants’ motives more than the judges’ bias: of course the state was going to disproportionately punish those trying to overthrow it.

But neither were the harshest sentences reserved for Republicans. Three of the four Specials convicted were sentenced to prison terms of a year or more, as were 38 of the 55 IRA members convicted; the proportions are 75% and 69% respectively. Of course, no Specials were sentenced to flogging, although nine IRA members were – the state would only go so far in punishing its own.

However, non-state loyalists who were convicted did generally get off more lightly – they were over-represented among those simply fined and under-represented among those receiving the harshest sentences. This might suggest a level of indulgence of loyalist violence on the part of the courts – but set against that potential criticism is the Disraeli St case where nine loyalists each got 18 months in jail for possession of two rifles between them.

In total, the police captured 99 rifles (including carbines and shotguns), 164 revolvers and 111 loose bombs, as well as seven full cases of bombs. This was obviously only a tiny proportion of all the illegally-held firearms in Belfast at the time, but it does reinforce the most notable conclusion of this study.

The scale of the violence in Belfast was such that the police were simply over-whelmed when it came to quelling it, either at the particular moment in time or in seeking to prosecute those responsible afterwards. All too often, when rioting erupted, they were forced to call on the British military for assistance in suppressing it – the police alone could not cope. Nor could they watch every derelict or burned-out building for the possible presence of snipers. Nor could they hope to catch the culprits who broke into peoples’ homes, killed them and then stole away, leaving no witnesses.

Similarly, there were simply too many weapons held illegally by too many groups for the police to ever capture more than a small fraction of them. Of course, it did not help that many of the weapons with which the violence was carried out were held legally – either in the police’s own barracks or issued to the Specials.

But even allowing for this state complicity, one stark fact underlines the powerlessness of the more conscientious Belfast police and of the courts when it came to firearms offences: 430 killings took place for which there was no legal sanction, but only 12 people were even prosecuted for murder and none were convicted.

References

1 Alexander Pulling (ed.), Defence of the Realm Acts and Regulations Passed and Made to July 31st, 1915 (London, Stationery Office, 1915), p27. The full text of the regulation was: “No person, without the written permission of the competent naval or military authority, shall, on or in the vicinity of any railway, or in or in the vicinity of any dock harbour or in or in the vicinity of any area which may be specified in an order made by the competent naval or military authority, be in possession of any explosive substance or any highly inflammable liquid, in quantities exceeding the immediate requirements of his business or occupation, or of any firearms or ammunition (except such shotguns, and ammunition therefor, as are ordinarily used for sporting purposes in the United Kingdom), and if any person contravenes this provision he shall be guilty of an offence against these regulations.”

2 Restoration of Order in Ireland Bill, The National Archive (UK), CAB\24\110.

3 Northern Whig, 16th February 1922.

4 Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland), 1922, https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/hmso/spa1922.htm

5 https://www.courts.ie/history-law-ireland

6 https://www.dib.ie/biography/henry-denis-stanislaus-a3939 I first came across this colourful phrase – which obviously cuts both ways – in an interview given by Rory Graham, the son of a Presbyterian minister, who was a Staff Captain attached to the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division leadership: “He said that, being a Protestant, he was a sort of white blackbird as far as the Catholic Irish Volunteers were concerned.” Notes of interview with Rory Graham, Louis O’Kane Collection, Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library & Archive, LOK IV B.04.

7 Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) e-catalogue, Crown Files, Assizes and Commission, BELF/1/1/2/61 [1920 files] – BELF/1/1/2/69 [1922 files]; Crown Files, General Assizes including Winter Assizes ANT/1/2/C/30 [1920 files] – ANT/1/2/C/30 [1922 files]. Any cases tried at the Down assizes or County Court related to offences outside Belfast. There were seven other murder charges brought which were unconnected to the political/sectarian violence at the time – they are not included in this analysis.

8 Belfast News-Letter, 24th & 25th November 1922; Occurrences in Belfast 31/5/1922, in File of reports by R.I.C. on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A.

9 Belfast Telegraph, 3rd February 1922.

10 Northern Whig, 25th May, 7th & 8th June 1922.

11 Northern Whig, 7th & 8th January 1921; Nominal roll of 3rd Northern Division, No. 1 Brigade, 2nd Battalion, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives (MA), MSPC-RO-404.

12 Belfast News-Letter, 27th & 30th September 1921; Belfast Telegraph, 27th October 1921; Northern Whig, 3rd December 1921; Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289. I am extremely grateful to Paddy Mulroe for sharing with me his research on this important file, which mainly focuses on loyalists.

13 Northern Whig, 22nd July & 21st August 1922; Nominal roll of 3rd Northern Division, No. 1 Brigade, 2nd Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC-RO-404.

14 Northern Whig, 20th June & 21st August 1922; Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289.

15 Belfast News-Letter, 28th March 1922; Northern Whig, 29th April 1922.

16 Northern Whig, 21st March 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 13th September 1922.

17 Northern Whig, 19th May 1922.

18 Northern Whig, 24th March 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 3rd May 1922.

19 Northern Whig, 24th November 1922.

20 Belfast Telegraph, 27th October & 28th November 1922.

21 Northern Whig, 22nd August 1922. Scott may actually have been bound over for a month – Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289; the file does not mention whether Armstrong or Brown were also dismissed.

22 Smith: Northern Whig, 9th May 1922 & Belfast Telegraph, 25th May 1922. Pollock: Belfast News-Letter, 11th July 1922 & Northern Whig, 21st August 1922. Quinn: Northern Whig, 8th July 1922 & Belfast News-Letter, 22nd November 1922.Nesbitt: Northern Whig, 2nd May & 21st August 1922, Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 1st & 8th March 1922.

24 Belfast News-Letter, 14th December 1920; Nominal roll of 3rd Northern Division, No. 1 Brigade, 2nd Battalion, MSPC, MA, MSPC-RO-404.

25 No record was found in the press of the sentences from eight cases, most of which were courts-martial where the prisoners were found guilty but “sentence will be promulgated in due course.”

26 Belfast News-Letter, 16th September 1921.

27 Belfast Telegraph, 6th August 1921.

28 Belfast News-Letter, 6th April & 18th May 1921; Patrick Begley file, MSPC, MA, 24SP07989.

29 Northern Whig, 2nd May 1921; Belfast Telegraph, 13th May 1921.

30 Four of those convicted were bound over, while three absconded to the Free State while on remand. No record was found in the press of the outcomes for 17 defendants – all four Belfast newspapers were on strike for a month from mid-July 1922, when many of these prisoners would have been sentenced.

31 Northern Whig, 27th May 1922; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 3rd June 1922.

32 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 15th October 1921; Northern Whig, 20th October 1921. Dolan does not appear on any list of IRA members.

33 The three were: B Special Constable Joseph Morgan (see note 23 above), C Special Constable Samuel Creed (Belfast News-Letter, 1st & 8th March 1922) and C Special Constable John Williamson (Northern Whig, 24th March & 4th April 1922). Williamson was subsequently interned: Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289.

34 Belfast News-Letter, 19th April 1922; Northern Whig, 4th May 1922.

35 Belfast News-Letter, 11th July 1922.

36 McWhinney: Belfast Telegraph, 2nd March 1922 & Northern Whig, 8th March 1922; Charles McWhinney file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF06084. Galway: Northern Whig, 3rd June 1922.

37 Belfast News-Letter, 27th March & 4th April 1922; Northern Whig, 28th April 1922; Arrest and internment of gunmen, PRONI, HA/32/1/289.

38 Northern Whig, 21st November 1922, Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 2nd December 1922 & 24th February 1923, Northern Whig, 26th February 1923. Thomas Waring evidently had an eventful couple of years, receiving gunshot wounds in September 1921 (Northern Whig, 21st September 1921) and being convicted of rioting the following February (Northern Whig, 28th February 1922).

39 Belfast Telegraph, 28th November & 9th December 1922; James Doherty file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF06059.

40 Belfast News-Letter, 5th July 1922.

41 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 20th July 1922, Richard Mulcahy papers, University College Dublin Archives, P7/B/77.

42 Belfast News-Letter, 3rd, 7th & 10th July 1922; Internment of Henry Crofton, PRONI, HA/5/961A.

43 Statement of Constable Patrick McNulty, Mountpottinger Barracks in Belfast outrages, National Archives of Ireland, TSCH/3/S11195. For more detail on these statements, see this previous blog post: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2023/08/26/the-ira-spy-who-joined-the-specials/ See also references at note 37 above.

44 Although it is slightly beyond the time-frame examined here, one case under-scores the degree to which some police were prepared to apply the firearms legislation: in January 1923, W.J. Morrow was arrested for illegal possession of a revolver and ammunition; the following month, he was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment – he was a soldier home on leave. Belfast Telegraph, 26th February 1923.

Leave a comment