There was widespread mistrust of the RIC among unionists. To what extent were their suspicions well-founded? This blog post examines the divided loyalties of some members of the RIC in Belfast.

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes.

Introduction

Unionists’ mistrust of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was expressed most forcefully by the Minister for Home Affairs in the first government of Northern Ireland, Sir Richard Dawson Bates – the man who had political responsibility for policing said:

“During the disturbances in the South of Ireland large numbers of the better type of [RIC] man were drafted to the south and men who could not be trusted or who were inefficient were sent into Belfast. Over 50 per cent of the force in the city are Roman Catholics, mainly from the South, and many of them are known to be related to Sinn Fein.”1

He clearly did not understand that RIC regulations forbade men from serving in their native counties. In addition, religion was not necessarily an automatic indicator of loyalty or disloyalty to the crown – for example, Sergeant Christy Clarke of the RIC’s “murder gang” was a Catholic.2

But to what extent were Dawson Bates’ suspicions well-founded?

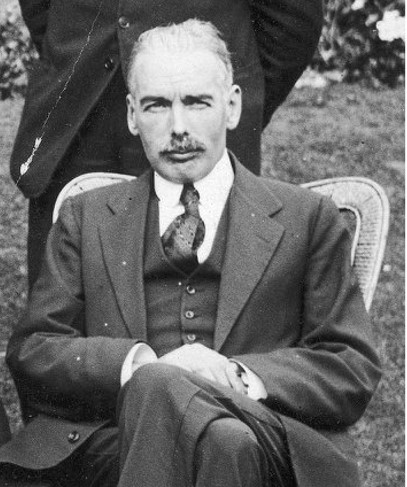

Sir Richard Dawson Bates

The start of the Pogrom

Constable Frank Greene of Mountpottinger Barracks in east Belfast was on duty when the Pogrom began in July 1920 and was confronted by rioting loyalists:

“When we were approaching the Convent grounds we were attacked by a howling Orange mob who threw bricks, bolts and nuts at us … We brought the military down from the chapel grounds on to Bryson Street in Newtownards Road corner. The few police present were again attacked by the Orange mob who called us ‘Sinn Fein policemen.’ I was the senior officer and I gave the order to the military to fire. They did fire and there were several casualties among the Orange mob.”3

At ground level, some loyalists’ distrust of the police was more visceral than Dawson Bates’ and they treated those they considered to be “Sinn Fein policemen” as Catholics first and policemen second:

“At about 10 o’clock at night, a mob attacked the dwelling-house of Sergeant Murphy, R.I.C., 2 Wellwood Street, between Sandy Row and Victoria Street. The crowd threw out part of the furniture and made a bonfire of it and also set fire to the house. Two houses adjoining were affected and before the arrival of the brigade the three houses were burned.”4

Some policemen struggled with the implications of the particular role which the RIC played in Ireland and concluded that they could not remain members – Constable James MacVeigh had been stationed in the Antrim Road Barracks, but resigned on 26th August 1920:

“As the struggle for national freedom continued to grow and the English Government’s policy became more repressive I knew that I should have to take an active part in carrying out that policy. This I could not, nor would not do for the ‘rebels’’ aims were my aims, and their sentiments were mine, and being in the enemy’s camp the only thing I could do was resign, which I did.”5

Similarly, Constable Charles Walsh of the Newtownards Road Barracks left the force on 14th September 1920:

“Resigned as a protest against the then Mayor MacSwiney’s imprisonment, also the uncurbed violence meted out to the Catholic people of Belfast, the disarming of the Belfast force during the riots and out of sympathy for the national movement.”6

Tip-offs and more

However, most Catholic members of the RIC continued to serve with the force, although not all continued to serve loyally and some even co-operated closely with the IRA in their local areas.

Dawson Bates had muttered darkly about some RIC men being related to republicans; he may have been fulminating rhetorically or he may actually have known of the family connection of one particular Sergeant – however, Henry Crofton, Quartermaster of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion in the city was keenly aware of it: “I knew two policemen, Sergeant Frank McKeon from Longford, a cousin of Sean McKeon’s [the commander of an IRA flying column in Longford], and Constable John Doherty, of Musgrave St. I knew the two of them personally and through them I got information of raids by the Crown forces.”7

Musgrave St Barracks

Sergeant McKeon was not the only relative of an IRA member serving in the city’s police – according to Manus O’Boyle, the first Captain of B Company, 2nd Battalion in Ballymacarrett: “My brother-in-law, Joe Clarke, who was a member of the R.I.C. stationed in the Shankill Road, Belfast, was one of our chief intelligence officers attached to the Belfast Brigade of the I.R.A.”8

O’Boyle also had a more local friendly contact in the RIC: “Another policeman I would like to mention was Constable McNulty of Ballina … He consistently gave us information and ammunition. He was stationed in [Mount]Pottinger Barracks and kept us posted regarding raids.”9

Across the city, Constable Thomas Conlon, of Springfield Road Barracks, also fed warnings to the IRA – according to IRA veteran Seán Montgomery, “he was good at giving tips of police raids.”10

Constable Thomas Conlon

Some policemen went beyond providing mere information – O’Boyle said:

“There was an Inspector of the R.I.C. I would like to mention too, J.J. McConnell. Mother Teresa [of the Cross & Passion Convent on the Newtownards Road] could always present us with hundreds of rounds of .45 ammunition which she received from him … We posed as a peace picket. When Inspector McConnell came in one day to a room in the Convent we were all assembled there sorting out ammunition – .37, .38 and .45. He said nothing except ‘So this is the peace picket,’ and walked away.”11

According to Crofton, “his” policemen even went beyond providing mere ammunition and began spiriting weapons out of their barracks armoury for use by the IRA:

“I got arms also from the same men for the organisation.

What arms did you get?

I got revolvers, several Webley revolvers. I don’t know how many.

From Doherty?

From McKenna [sic – McKeon] and Doherty for the organisation, and I exchanged bad ones with them for good ones, old things that we had that were defective I used to hand them to Doherty and McKenna and they would give me good ones instead.”12

Remarkably, Montgomery claimed that one attempted incursion into the nationalist Lower Falls area by members of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC or “Specials”) was driven off by the combined efforts of the IRA and RIC: “Trouble broke out as a mob of B Specials tried to come onto the Falls Road but were stopped by D Company with some help from some Dover Street Barrack men.”13

The most extreme (attempted) co-operation was that provided by an un-named member of the RIC stationed in Musgrave St Barracks in May 1922. In preparation for the IRA’s Northern Offensive, the Belfast Brigade devised a plan to steal armoured cars, rifles and ammunition from the barracks on the eve of the offensive. According to Séamus Woods, O/C of the 3rd Northern Division, who led the operation, “We had co-operation from a … [name redacted] who opened the door and admitted the whole party of twenty-one while he kept a watch on two Police who were on guard at the rear of the Detective office.” However, the alarm was raised and the IRA raiding party had to make off empty-handed.14

Police suspicions of policemen

The late Joe Baker was a local historian of Belfast, in particular of north Belfast – he wrote that: “Glenravel Street Barracks … during the partition of Ireland, was known as the ‘Fenian Barrack’ because of the high number of Catholic R.I.C. men who served there.”15

For some Catholic policemen, suspicions and accusations on the part of fellow-officers would eventually escalate to the point where their lives were threatened. Constable Peter Flanagan was stationed in Brown Square Barracks; in early 1922, he described how:

“In June last some shooting took place about the district into the Catholic quarter. I was on duty in the Catholic quarter. No firing took place from that quarter. Three or four regular R.I.C. Protestants rushed into the street fully armed and were preparing to fire on the people. I prevented them. They told me I was in sympathy with Sinn Fein. We had words every day after that and on 21st June those men sent me my death notice … I asked for a transfer on grounds of my life being in danger but it was refused by Mr. Gelson [sic – Gelston] the Commissioner. About a fortnight ago another Catholic Policeman and I were in the Barracks. In the room there were two or three Protestant R.I.C. and 12 to 14 ‘Specials’ … We were charged with being Sinn Feiners by the regular police and with giving this information to the Sinn Feiners. They said we should be kicked out of the Barracks. The ‘Specials’ said we should be shot first and thrown through the windows. We complained of this. No steps were taken to prevent a repetition.”16

Brown Square Barracks

Brown Square Barracks was the main station in the area for which the notorious District Inspector John Nixon was responsible. One of the other barracks in his “C District” was that at Leopold St, just off the Crumlin Road, facing Ardoyne, and Nixon had deep misgivings about the loyalty – or lack of – among some of the officers stationed there; in July 1922, he wrote an open letter for public circulation:

“On the 4th January 1922, I saw Father Sebastian, rector of Ardoyne, coming out of the [RIC City] commissioner’s office. A little later the commissioner came out. The same evening an order was issued to me from the commissioner that Special Constabulary were not [to] be employed in the Ardoyne and Bone areas. This was emphasised several times subsequently, and in the end no Police but the Leopold Street men were allowed to be used there.

Many of the Leopold Street police were in sympathy with the I.R.A., and the result of the order was, that from that day on the I.R.A. got a bit out of hand and committed various murders and other outrages.”17

Police informing on policemen

But around the time that Nixon was complaining about the police in Leopold St, some of those very same policemen were telling the Provisional Government what they, in turn, knew about Nixon.

In mid-March 1922, Patrick O’Driscoll was sent to Belfast by Michael Collins to act as an investigator on his behalf; many in senior southern political and military circles doubted the veracity of the reports of Pogrom violence being sent to them by the Belfast IRA, so Collins sent O’Driscoll north to find out for himself.

On 22nd and 23rd March, O’Driscoll interviewed and took statements from a number of sympathetic RIC Sergeants and Constables. What is striking is that – even in advance of the McMahon family killings – Nixon’s role in the RIC “murder gang” was already common knowledge among these men. One of the Leopold St policemen who talked to O’Driscoll was Constable Andrew McCloskey:

Leopold St Barracks

“Nixon has working for him a crowd of plain clothes men. These are supposed to be engaged in the rounding up of the robber and hold-up gang. There are eight men in the Gang. One of them is a Catholic, a man named Scanlan from the South of Ireland. He came here recently for his own safety. The others are Gordon, Tipping, Sterritt, Preston, Norrys, Sherwood and Hare. These are the old R.I.C. They are out for the purpose of shooting I.R.A. men and failing that, shooting any Catholics.”18

Constable Michael Furlong, also stationed in Leopold St Barracks, described how Nixon was covering for and turning a blind eye to the illegal activities of the Specials:

“One night in January last I seized two revolvers on a ‘B’ Special named Adair, living in 335 Old Lodge Road, seized them at his residence. They were not service revolvers – one of them was a Turkish revolver, and the other was of the small Webley pattern … I took charge of them. When I got back to the Barracks I wrote a report of the seizure. I hadn’t handed in this next morning when District Inspector Nixon rang me up on the telephone. He asked me if I seized a revolver from a ‘B’ Special on the previous night. I said I seized two of them and 29 rounds of ammunition. He asked me on whose authority I did that. I told him on the authority of a military officer who reported that he had information Adair had been sniping. Nixon told me I was a blackguard and if I didn’t stop my blackguardism he would get me out of his district in 24 hours … He ordered me to bring down these revolvers to his office at once. I took the arms and ammunition to Nixon’s office in Brown Square Barracks immediately … He took the revolvers and ammunition and handed them to Adair telling him to take them home.”19

Nixon’s reach and his protection of Specials extended beyond his own district and across the river to Ballymacarrett. Constable Greene of Mountpottinger Barracks said:

“One evening at the corner of Newtownards Road and the Short Strand, a Special named Glass was arrested. He had been seen by the police firing off a tram and killing a Catholic in Seaforth [sic – Seaforde] Street. When arrested he had two loaded revolvers in his possession. Nobody seemed to know him. I knew I saw his face previously and I recalled to mind where I had seen him. It was in the dock at the previous Assizes. At the time I saw him in the dock he had been charged with murdering a Catholic in Derry City. He turned out to be an ‘A’ Special. The police at Mount Pottinger Barracks communicated with Brown Square Barracks. That night the man was liberated, though caught red-handed … Do you know who the man was? He was chauffeur to Nixon, D.I., the Deputy Chief of the Murder Gang. On the following evening to show that this murderer still retained his confidence Nixon took Glass along with him in the car to the Newtownards Road. D.I. Nixon was driving himself, this man was sitting behind him with his arms crossed.”20

Another member of the “murder gang,” Sergeant Christy Clarke, was mentioned in the statement of Sergeant John Murphy of Springfield Road Barracks – this may well have been the same Sergeant Murphy who was burned out of his home near Sandy Row in 1920; Clarke was probably at the forefront of Murphy’s mind as just ten days earlier, the IRA had killed Clarke on the Falls Road:

“There was a move on foot to get the ‘Specials’ out of Springfield Road – or at least there was a rumour they were going. I heard three of them say deliberately that before they would leave they would do in five or six on the Falls Road. The names of these three ‘Specials’ are Bailey, Reed and Wilson. Strange to say Christy Clarke was the most in favour of keeping them on. Even District Inspector Deignan was for sending them away. Christy Clarke said that no matter what D.I. Deignan would do that he would bet ten to one that the ‘Specials’ would be there in spite of him. He was in charge of the few ‘Specials’ and was going around with them in the Lancia car and he didn’t want them to go.”21

Springfield Road Barracks, where Sergeant John Murphy was based

A different member of the “murder gang,” Head Constable Pakenham, appeared in another statement; although he was not named here as a member of the gang, he was included in a list of its members in a dossier later prepared for the Free State Government.22 Sergeant John Bruin of Henry St Barracks in north Belfast described both Pakenham and a Unionist MP leading an attack on Catholics living in the area:

“…an immense crowd congregated on the front of York St. Garmoyle St. The regular R.I.C. on duty kept this crowd pushed back as well as they could. They were restoring order and preventing shootings and murders, until the arrival of two or three cars of ‘Specials’ in charge of Head Constable Pakenham of Court St. Barracks. Head Constable Pakenham had a short conversation with the hooligan mob in front of York St. This numbered about 5,000. After the conversation with the crowd Pakenham and his party made a rush down into a Catholic street. They started bursting in the doors and shouting ‘we will turn out the Sinn Feiners’ … the ‘Specials’ burst in the doors of every house belonging to the Catholics. They smashed the furniture, looted the houses and robbed numbers of people. The mob helped them to wreck and loot. Amongst the mob that day was the local member Grant M.P. who led the looters and wreckers.”23

Henry St Barracks, where Sergeant John Bruin was stationed

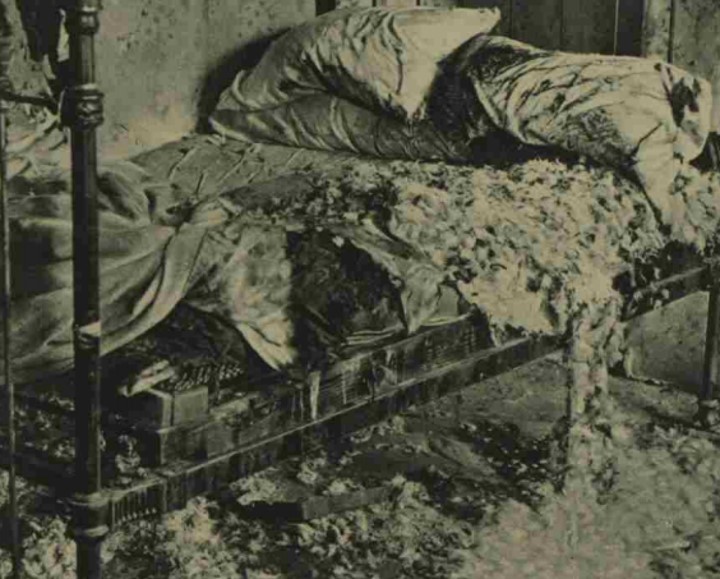

Another policeman stationed in Mountpottinger Barracks, Constable William Duffy, witnessed a fatal bomb attack perpetrated by loyalists in Ballymacarrett:

“On Saturday 18th March at 5 a.m. there were 30 to 40 men on the Albert Bridge Road, with rifles and revolvers firing into Thompson Street and Short Strand – Catholic quarters. At the same time, one man, accompanied by four men with rifles, went down into Thompson Street and threw an incendiary bomb into 32 Thompson Street killing Miss Mullan and seriously wounding her aunt, Mrs Greevy, Catholics. One of these men was dressed in khaki. The four men seemed to be ‘Specials’ and wore trench coats.”24

The aftermath of the Thompson St bombing (Illustrated London News, 25th March 1922)

Feeding intelligence to the IRA

Apart from the RIC members who were interviewed by O’Driscoll, there was clearly a wider network of sympathetic policemen who were providing the Intelligence Department of the Belfast IRA with information. For example, by early 1922, this had allowed the IRA to build up a detailed picture of the strengths of regular RIC and A Specials at most of the 26 Belfast barracks as well as the Detective Unit in Chichester St.

Unsurprisingly, the three barracks of A District, which was responsible for the city centre, had the largest number, with 181 regular RIC and 74 Specials. B District, with four barracks in west Belfast. had 201 RIC and 10 Specials, although there were no numbers given for Specials in Cullingtree Road or Brickfields (Dover Street) Barracks.

DI Nixon’s C District had a total of 137, although curiously, given his view of Leopold St Barracks being infested with Sinn Féin sympathisers, it was not included on the list – nor were numbers provided for Craven St or the Shankill Road Barracks. D District covered north Belfast and had 149 regular RIC and 22 Specials between five barracks; however, three of these were in outlying areas and the two in central north Belfast – Glenravel St and Henry St – only had a total of 100 RIC and Specials between them. This relatively low police presence may have been a contributory factor to this being the worst part of Belfast in terms of killings during the Pogrom.

The four barracks of E District covered east Belfast, but there were no numbers provided except for Mountpottinger Barracks, which had 100 regular RIC (no number was given for Specials). The four barracks of F District in south Belfast had only 80 in total although no figures were provided for Donegall Road Barracks.25

Apart from this, there were 40 A Specials in a dedicated barracks at Court St around the corner from the Crumlin Road courthouse, under the command of Head Constable Pakenham, as well as another 42 at two outposts in the Market area. For obvious reasons, it was harder to get a picture of the numerical strength of the B Specials, although the IRA did know the identities – and in some cases, even the home addresses – of the District Commandants in each of the six districts: Shankill Road, Lisburn Road, Ardoyne, Antrim Road, Ballygomartin and Dunmurry.26

The IRA spy who joined the Specials

However, for all this information being fed to them by sympathetic policemen, the single most prized asset of the Belfast IRA’s Intelligence Department was a man named Pat Stapleton.

During the Great War, Stapleton, a Catholic from west Belfast, had been a Lieutenant in the Royal Irish Rifles and it was undoubtedly this record of loyal wartime service in one of the component units of the 36th Ulster Division which helped him secure a job as a civilian clerk in Victoria Barracks in November 1920.27

Victoria Barracks, where Pat Stapleton worked as a clerk (© National Library of Ireland L_ROY_02390)

At some later point, he approached the IRA and offered to provide them with information. The Belfast Brigade’s Intelligence Officer, David McGuinness, recalled:

“The routine method we adopted was that certain files were abstracted each night except, of course, when there was a sign of unusual activity in or around the barracks and there was a danger of a search. By arrangement, these files were handed over to us in St Mary’s Catholic Church. Donegan and I sat up the whole night copying these files in their entirety, and we handed them back the next morning in St Mary’s Catholic Church. In a few short months we had practically completed a copy of every important file in the Military Headquarters.”28

In the summer of 1922, Stapleton was given an opportunity to work in a much more valuable position from the IRA’s point of view:

“Around this time an offer was made to our contact to have him transferred to the Royal Ulster Constabulary [RUC], also in a civilian capacity … He (our contact) took up duty as Confidential Clerk to Major-General Solly-Flood at Waring Street Headquarters. The same procedure was carried out here as at Victoria Barracks and when a suitable occasion presented itself the files were abstracted, brought to us to be copied and returned the following morning. Our contact continued doing his work efficiently up to about June 1922.”29

L: Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood, Military Advisor to the Unionist government; R: RUC Headquarters, Atlantic Buildings, Waring St

At the beginning of August, Stapleton and two other clerks from Solly-Flood’s office were enrolled in the A Specials and added to its payroll – he presumably went along with this in order to keep his cover intact. Although the RUC were aware of Stapleton’s religion, he had been given such a good reference by the military authorities in Victoria Barracks that he was not vetted more thoroughly.30

Shortly after this, Stapleton began acting nervously – the RUC subsequently believed this was because he had run into embarrassing financial problems, but McGuinness knew that the real reason lay in the split within the Belfast IRA:

“The Intelligence Officer of the Executive Forces in the Belfast area having had previous knowledge of our contact’s work with our Intelligence Department made several attempts to wean him to their side and to get him to supply them with the material he was supplying to us. The contact sensed a danger in this dual connection and fought shy of it. Later he was menaced and threatened of personal injury which forced him to board in another part of the City. This caused a drying up of our information for a number of weeks. We took steps to contact him again, found out where he was living and thrashed the matter out with him … Relations were again resumed on the old terms and the flow of information continued as before until further uneasiness developed on the part of our contact.”31

But by late August, Stapleton had had enough of the life of a spy and wanted to leave Belfast to join the Garda Síochána in the south:

“This did not make us feel too happy as we saw in it our most valuable source of information dry up, so after consultation we decided to make the best of a bad bargain and finish the chapter with a ‘grand slam,’ that is a list of the most important files then available, secret dossiers, etc., the compilation of which we had some knowledge. We therefore instructed the contact to collect as many of these files as possible. This seemed to put him in a panic and we lost trace of him for several weeks, but eventually we prevailed on him to carry out our plan.

By arrangement Donegan and myself met him on a Saturday evening for the purpose of entering Police Headquarters and helping ourselves to the required material. Our contact, at the last minute, funked taking us with him and insisted that we remain outside while he entered alone. A half hour later he left the premises, followed us some hundred yards away where we entered a public-house and in a secluded spot we took charge of some dozen or so files all marked ‘Secret and Confidential.’ … We gave our contact a stiff drink to steady his nerves.”32

Ben Donegan, McGuinness’ assistant, took Stapleton to the station and put him on the next train to Dublin.

What neither Stapleton nor McGuinness knew was that, even prior to his absconding, Stapleton had already been reported to the police authorities: “On or about 17th August Stapleton came to me to borrow some money, and on hearing that he had already borrowed certain sums from other people in the office, I mentioned the matter to Major Baxter, who requested the Detective Branch, R.U.C., to make enquiries as to his reliability.” A detective interviewed Stapleton’s landlady at his lodgings on Botanic Avenue: “She has no reason to doubt his loyalty but describes him as flippant and full of self praise … As far as the police can ascertain this man has no disloyal tendencies.”33

When Stapleton made his final theft of files on 19th August, there was a bout of recriminations between the RUC, British Army and Solly-Flood’s office over who should have, who had and who had not checked out Stapleton’s trustworthiness. Various officials were also keen to downplay the significance of the files he had stolen; however, the subject matter of some of the files suggest that the contents may have been juicier than Solly-Flood’s staff were prepared to admit:

- Spire of St. Malachi’s Chapel for Wireless

- Recruiting of C1 Specials

- Defence of H.M. Prison, Belfast

- Prison at Larne

- Belleek-Pettigo Neutral Zone

By 10th October, Solly-Flood himself had to write to the Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, admitting that “No definite information as to the whereabouts of the above named man is at the moment in our possession;” nevertheless, he gamely continued to insist that “Definite information is however to hand that up to the 6th October none of the documents he is alleged to have taken have reached Beggars Bush G.H.Q.”34

But according to McGuinness, the files were handed over to Woods the morning after being stolen and he brought them to Dublin immediately “…and so ended the chapter. After that our big scale intelligence work came to an end.”35

After the Pogrom

The only biography or autobiography of a nationalist member of the RIC in the north is that of John McKenna who, in terms of political outlook, was a self-described Home Ruler rather than a republican. He was a Head Constable stationed in Cookstown, County Tyrone, and he described his constant efforts to stymie and thwart the violent sectarian urges of the B Specials under his command; such actions were echoed in some of the interviews collected in Belfast by O’Driscoll. McKenna’s autobiography is aptly titled A Beleaguered Station.36

What happened to the Belfast IRA’s helpful policemen after the Pogrom?

Two of them did not even survive the Pogrom. Ironically, Constable Conlon of Springfield Road Barracks was killed in an IRA ambush in Raglan St in the Lower Falls on 10th July 1921, the day before the Truce was supposed to come into effect. On 20th April 1922, less than a month after giving his statement to O’Driscoll, Sergeant Bruin was killed during the armed robbery of a pub in York St.

DI J.J. McConnell (at front, carrying cane) leading guard of honour at funeral of Constable Jim Galvin (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 16th July 1921)

DI McConnell was transferred from Mountpottinger to Glenravel St Barracks – his appointment there may well have contributed to it earning the sobriquet of the “Fenian Barracks.” He was still there in July 1921, when he was pictured leading the RIC guard of honour at the funeral of Constable Jim Galvin of that barracks, who was killed on 8th July. But according to O’Boyle,

“A short time after an attempt was made on his life and he was transferred to Cork. When he was telling me about it at the Convent he said ‘This is the end of me.’ I replied ‘I don’t think so.’ I went to see Joe McKelvey that night and told the whole thing to him. He immediately placed the matter in the hands of Frank Crummy [sic] who took the necessary steps which must have been effective … On his journey to Cork he was approached by railway officials at different stations who enquired about his comfort. Also he said there was never an ambush when he was a member of a patrol in Cork.”37

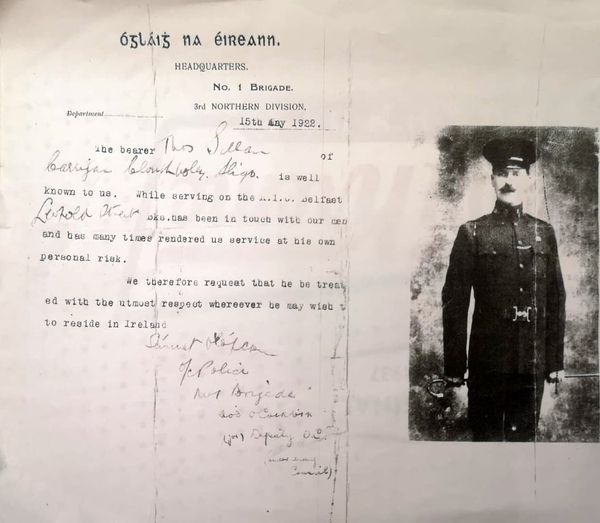

McConnell was not the only member of the RIC to be promised safety as a reward for the help he had provided to the IRA in Belfast. In May 1922, Constable Thomas Gillan of Leopold St Barracks received a typewritten promise of safe passage from the O/C of the IRA Republican Police in Belfast; it is clear from the document that this was a form created with spaces left for writing in the name and barracks of the policeman concerned, suggesting that Gillan was not the only recipient of such a document.

IRA promise of safe passage for Constable Thomas Gillan of Leopold St Barracks

One ex-policeman received a much more lavish reward than a mere promise of safe passage – O’Boyle’s brother-in-law, Constable Clarke, “…left the R.I.C. and went to America as did many others. Prior to leaving he was presented with a beautiful gold watch by Joe McKelvey on behalf of the Division.”38

The jewel in the crown of the IRA’s Intelligence Department, Stapleton, did eventually join the Gardaí and he rose to the rank of Superintendent.39

At a more general level, the RIC was disbanded at the end of May 1922 and, from 1st June, replaced by the RUC. While Head Constable McKenna lived in Larne after disbandment, 126 former RIC men, formerly stationed in Belfast, moved to the Free State. Many, if not most, of these would simply have been returning to their native counties and not all were necessarily sympathetic to the IRA or Sinn Féin, but given the IRA’s assessment that there were only 872 regular RIC in total across 19 of the 26 Belfast barracks, it does suggest that a substantial number of the Catholics among them simply did not want to live in the new Northern Ireland under its particular political dispensation.40

Among the 126 were two of O’Driscoll’s interviewees – Constables McNulty and O’Neill. Of the others, Constable Furlong stayed in Belfast, while Constable Monaghan returned to his native Fermanagh and three moved to England, one later returning to Belfast. The destinations of Constables McCloskey and Flanagan are unclear.41

In November 1922, the Free State government set up a committee to investigate the cases of former RIC members who had resigned or been dismissed from the force between the start of the War of Independence and the Truce on account of their “national sympathies;” the remit of the committee was later extended to cover all such cases since the Easter Rising. The committee provided an interim report in April 1923 – at that point, out of 1,094 applications, 492 had been approved, 414 rejected and 188 were still under consideration. As the men involved had lost their incomes and pensions, a Superannuation and Pensions Act was passed in 1923 to compensate them.42

Report of the Committee of Enquiry into Resignations and Dismissals from the RIC (© Military Archives)

Ignoring those who had resigned prior to the outbreak of the Pogrom, there were 27 former members who had resigned in the north but were now living in the Free State – again, most likely simply returning to where they were from. There were a further 22 successful applicants who – like McKenna – were still living in the north. Unfortunately, the committee’s report does not specify where in the north they had been stationed. A further three had served in the north, two of them in Belfast, but were now living in the USA.43

However, the 492 who resigned due to their “national sympathies” were dwarfed by the numbers who resigned, either as a result of the boycott and social ostracism of RIC members and their families instituted by the Dáil or due to intimidation and attacks by the IRA: “…resignations slightly increased from 1,090 in the second half of 1920 to 1,189 in the first seven months of 1921.” Most importantly, those who resigned for nationalist reasons paled in comparison with those remained in the RIC: “Nevertheless, 63 percent of the men who were members of the R.I.C. in January 1919 [roughly 9,000] were still enrolled at disbandment in 1922.” The sympathies of these men clearly lay elsewhere.44

Finally, after disbandment, the direction of travel of former RIC members was not all north-south: “…by February 1923, the 2,000-strong R.U.C. provided employment for 1,347 R.I.C. veterans, 505 of whom were Catholic.”45

Summary and conclusions

In January 2020, the Irish Minister for Justice, Charlie Flanagan, announced plans to hold a state commemoration for the RIC as part of the Decade of Centenaries. This was met with a storm of public opposition from historians and other commentators who pointed out that, apart from commemorating those who had fought to prevent the state from coming into existence, it would involve commemorating both the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries. Similarly, in the north, the RIC included as an integral and critically important component the Special Constabulary, whose treatment of those who aspired to become citizens of the state hardly merited respectful remembrance by the children and grandchildren of their victims. Flanagan swiftly dropped the proposal.46

Nothing in this blog post should be construed as attempting to rehabilitate the reputation of the RIC as an organisation. It was the first line of defence of British imperial rule in Ireland and was armed to enforce that rule – in that respect, it was far from a normal police force such as constabularies in Britain or the Garda Síochána.

However, it was predominantly composed of Irish men, some of whom, at an individual level, shared the aspirations for independence of the revolutionary movement. This was also the case in Belfast, where the demographic and political context meant the independence struggle faced intense opposition, channelled into sectarian violence.

Some RIC members in the city could not countenance being part of that opposition and resigned. Others, perhaps more courageously, opted to remain in the RIC but quietly provided assistance to the IRA in various forms – warnings, information, intelligence, arms and ammunition.

Dawson Bates’ low opinion of the RIC was based on a nakedly sectarian conviction that the force was too Catholic to be trusted. Other prominent Unionist politicians shared his view, leading James Craig to press London for the initial creation of the Special Constabulary in the autumn of 1920, a force that was recruited in such a way as to provide one that was much more to their liking. It was also clearly to the liking of senior RIC officers such as DI Nixon, or non-commissioned officers like Head Constable Pakenham, who could then use it and thus bypass the regular RIC, which they viewed as being riddled with “Sinn Fein policemen.”

However, the admittedly modest contribution of a network of supportive Belfast RIC men – and one Special Constable – to the republican cause suggest that unionists’ fears were not entirely misplaced.

References

1 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), pp13-14.

2 The then Constable Clarke’s 1911 Census return can be viewed at: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai001503247/

3 Statement of Constable Frank Green, Mountpottinger Barracks, Belfast outrages, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), TSCH/3/S11195.

4 Irish News, 31st August 1920.

5 Application forms to Committee of Enquiry into Resignations and Dismissals from the Royal Irish Constabulary, Military Intelligence and Press Analysis – Civil War (MIPR Collection), Military Archives (MA), MIPR 03 13.

6 Ibid.

7 Henry Crofton file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), MA, MSP34REF106.

8 Manus O’Boyle statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), MA, WS0289.

9 Ibid.

10 Statement of Seán Montgomery, Seán O’Mahony Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 44,061/6.

11 Manus O’Boyle statement, BMH, MA, WS0289.

12 Henry Crofton file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF106.

13 Statement of Seán Montgomery, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6. Brickfields Barracks was known locally as “Dover Street Barracks.”

14 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 19th May 1922, Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archives (UCDA), P7/a/173.

15 Joe Baker, North Belfast – A Scattered History (Belfast, Belfast History Project, n.d.), p63.

16 Statement of Constable Peter Flanagan, Brown Square Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

17 Tim Wilson, ‘“The most terrible assassination that has yet stained the name of Belfast”: the McMahon Murders in Context’, in Irish Historical Studies, Volume 37, Issue 145 (May 2010), p83-106.

18 Statement of Constable Andrew McCloskey, Leopold St Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

19 Statement of Constable Furlong, Leopold St Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

20 Statement of Constable Frank Green, Mountpottinger Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

21 Statement of Sergeant John Murphy, Springfield Rd Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

22 Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Ernest Blythe Papers, UCDA, P24/176.

23 Statement of Sergeant Bruen [sic – Bruin], Henry St Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195. Originally a shipyard worker, William Grant was a leading member of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association; he was elected as an MP for North Belfast in May 1921.

24 Statement of Constable William Duffy, Mountpottinger Barracks, Belfast outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195. Mary Mullan and Rose McGreevy were both killed in this attack.

25 All figures for RIC and Specials manning levels at each barracks are taken from: Internment of Henry Crofton, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/961A.

26 Ibid.

27 Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, one of the Military Adviser’s staff, PRONI, HA/32/1/271.

28 David McGuinness statement, BMH, MA, WS0417.

29 Ibid.

30 Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, PRONI, HA/32/1/271.

31 David McGuinness statement, BMH, MA, WS0417.

32 Ibid.

33 Enquiry into disappearance of A.T.P. Stapleton, PRONI, HA/32/1/271.

34 Ibid. The late Dr Éamon Phoenix told me that he remembered seeing the original files which Stapleton stole at one of the annual releases of state papers by the National Archives in Dublin. Unfortunately, he was unable to recall the NAI reference numbers, nor have I been able to trace them in NAI; email from Éamon Phoenix, 10th August 2021.

35 David McGuinness statement, BMH, MA, WS0417.

36 John McKenna, A Beleaguered Station – The Memoir of Head Constable John McKenna, 1891-1921 (Newtownards, Ulster Historical Foundation, 2011).

37 Manus O’Boyle statement, BMH, MA, WS0289.

38 Ibid.

39 David McGuinness statement, BMH, MA, WS0417.

40 Seán William Gannon, author of The Irish Imperial Service: Policing Palestine and Administering the Empire (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), very kindly shared the results of his research into the disbandment of the RIC with me. As I have said before, normally I follow historians’ footnotes in the same way that Hansel and Gretel followed the trail of breadcrumbs – but once in a while, someone just gives you the whole gingerbread house.

41 Ibid.

42 https://www.militaryarchives.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/Documents_2/2020/Interim_Report_COMPLETE_PDF.pdf

43 Ibid; Application forms to Committee of Enquiry into Resignations and Dismissals from the Royal Irish Constabulary, MIPR Collection, MA, MIPR 03 13.

44 W.J. Lowe, “The War Against the R.I.C., 1919–21”, in Éire-Ireland, Volume 37 No. 3 (Autumn/Winter 2002), p79-117.

45 Kent Fedorowich, “The problems of disbandment: the Royal Irish Constabulary and imperial migration, 1919-29”, in Irish Historical Studies, Volume 30, Issue 117 (May 1996), p88-110.

46 See, for example, Brian Hanley, “The RIC was never a normal police force; commemorating it would be a travesty”, Irish Times, 13th January 2020.

Leave a comment