The fog of war and chaos of rioting do not completely obscure who carried out the killings in Belfast during the Pogrom. This blog post explores the extent to which responsibility for those killings can be attributed.

Estimated reading time: 45 minutes.

Introduction

Referring to the deaths of civilians in Belfast, Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin said in The Dead of the Irish Revolution that: “In many of these cases it is impossible to be certain of responsibility for individual fatalities, because up to six discrete armed groups – loyalist paramilitaries and civilians, nationalist civilians, the IRA, military and police (including USC) were involved.”1

For the period covered by their book – up to the end of December 1921 – there were 175 civilians killed in Belfast and it is actually possible to say with a reasonable degree of certainty who killed all but 76 of those. O’Halpin and Ó Corráin continued:

“While it can reasonably be argued that the majority of these civilian deaths arose from intercommunal sectarian violence, in many instances it is uncertain whether a fatality was specifically targeted on grounds of religion, or was even the intended target of the bullet or bomb that killed her or him.”2

This is partly true in relation to the time frame they have examined, when the vast majority of civilian deaths were due to rioting, but does not hold for 1922, as the predominant setting for killings moved from rioting to a combination of close-range and sniper attacks, when the killers’ targets were selected precisely on grounds of religion.

In addition to civilians, 78 combatants died as a result of the Pogrom and it is possible to assign agency in all but eight of those cases.

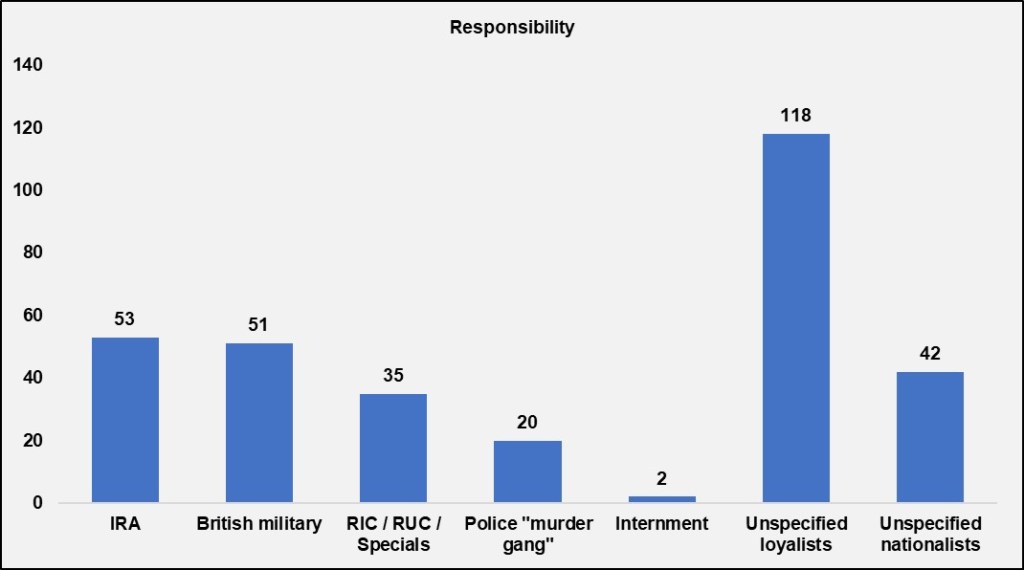

Of the 501 fatalities in Belfast, a considerable number remain unattributable: 180, or 36% of the total, for precisely the reasons outlined by O’Halpin and Ó Corráin – there were too many potential killers at work to be certain who killed whom. This post concentrates on the 64% of killings – almost two-thirds – for which, with varying degrees of precision, it is possible to say who was responsible.

Killings by the IRA

In terms of killings that can be attributed to a particular organisation, the IRA killed 53 people, more than any other single combatant group: 27 members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”), two loyalist combatants, 21 unionist and three nationalist civilians.

Thanks to the richness of the archival material held by Military Archives, in both the Bureau of Military History (BMH) witness statements and the files of the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), we even know the individual identities of those involved in many of the killings for which the IRA was responsible, particularly ones in which regular RIC or Specials died.

For example, the very first policeman to be killed, Constable Thomas Leonard, was shot dead while being disarmed by a group of IRA on the Falls Road on 25th September 1920 – according to Tom McNally, this group included the local company captain, Aloysius “Wish” Fox, Johnny Osborne, Charlie Ryan and McNally himself.3

An IRA Active Service Unit was responsible for the killings of two southern-based RIC officers in January 1921, three Black and Tans in March of the same year, and two Auxiliaries the following month. This unit varied in composition for different operations, but at various times, it included Séamus Woods, Roger McCorley, Joe Murray, Séamus McKenna, Seán Keenan and Seán Montgomery. McCorley, Murray and McKenna all provided BMH statements detailing their involvement in these attacks, while Montgomery left an unpublished memoir which covers similar ground to the BMH statements.4

The MSPC is also a rich source of detail on IRA killings. In a reference supporting McCorley’s application supplied by former Belfast Brigade O/C Seán O’Neill, the former is named as the man responsible for shooting dead police “murder gang” member Constable James Glover on the Falls Road on 10th June 1921. In their applications, both Séamus Timoney and Henry Crofton state that they were among the party of IRA who killed two Special Constables in May St on 23rd March 1922.5

Altogether, the IRA was responsible for killing 27 of the 32 regular RIC and Specials killed in Belfast during the Pogrom – in all but nine of those cases, the names of some or all of the IRA men involved are known.

Séamus Timoney, one of the IRA men who killed two Specials in May St on 23rd March 1922 (photo courtesy Emily Twomey)

For the killings of unionist civilians, some assumptions need to be made.

The IRA had several workshops dotted around the city in which home-made munitions were made. According to Cumann na mBan activist Mary Russell, “We had a place in Ch[ich]ester Street where they made the hand-grenades and stuff.”6 This place closed down after an accidental explosion, but their factory in Arizona St in Andersonstown remained undetected for two years and had 16 paid staff working in shifts:

“Were you paid the entire time for 2 yrs?

Yes.

What kind of work?

Making hand-grenades and land mines – moulding.

Who was in charge of the place?

Seamus McArdle, Divisional Engineer, and Joseph Cullen, Bde. [Brigade] Engineer.

Were there many employed in it?

There were 8 on the day shift and 8 on the night shift.”7

In addition, the IRA is known to have imported a quantity of Thompson submachine guns from the United States in 1921; some of these were subsequently sent to Belfast. As there is no evidence of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) in the city having access to either hand-grenades or submachine guns, it is assumed that any attacks on unionist civilians using such weapons were carried out by the IRA.

Fourteen unionist civilians were killed in bomb (hand-grenade) attacks, while James Greer was killed on 19th April 1922 when “a man in civilian attire came out in the middle of Thompson Street with a machine-gun and, kneeling down, fired a round of shots towards Beechfield Street.”8 The IRA is assumed to be responsible for all of these killings. It is also assumed to have carried out the sectarian killing of three Protestant workmen in a cooper’s yard in Little Patrick St in May 1922.

Other unionist civilians killed by the IRA included Alexander Allen, a bystander shot dead on 13th March 1921 in an attack on Black and Tans, and Leopold Leonard, killed on Peters Hill on 31st August 1921 in a sniper attack specifically attributed to the IRA by the inquest jury.9

The most high-profile civilian killed by the IRA was Unionist MP William Twadell, shot dead in Garfield St in the city centre on 22nd May 1922; this killing directly prompted the Unionist government to invoke the internment provisions of the Special Powers Act passed the previous month.10

The aftermath of the killing of Unionist MP William Twadell

In contrast to the attacks on regular police and Specials, when it came to attacks on unionist civilians, IRA veterans were noticeably more reticent about identifying those responsible. However, one who was somewhat less tight-lipped was Montgomery, who identified the man responsible for the bombing of a tram in Royal Avenue in November 1921, in which four men were killed:

“Things were getting very bad so orders were given to bomb two shipyard trams, one was done in Corporation Street in the early part of the week. In Lancaster Street I was approached by Alf Mullan. He could not get anyone to cover him as he had orders to do two trams. I asked him if it was an order and he said it was so I went with him. We went to the York Street face of the Belfast Co-op. An armoured car came along so we moved to Winetavern Street. While waiting a policeman who knew Alf told him to get to hell from there as he was on duty, so we went off to Berry Street and in front of the Grand Central Hotel he did the job. I covered him … Well there was a bit of a stink about it.”11

Montgomery also named the men responsible for shooting Twadell – Tommy Geehan and P. McAleese.12

Apart from David Cunningham, a member of the Ulster Imperial Guards killed by a bomb thrown on the Newtownards Road on 22nd November 1921, one other Imperial Guard was killed by the IRA – Alex Reid, shot dead in Cromac St in the Market on 30th November 1921:

“After the start of the Pogrom in Belfast, a Protestant organisation was got together under the care of a man named Callow. I do not remember the name of the organisation he controlled, but its principal purpose was to shoot Catholics in their homes and in workshops where they found a Catholic man working in a Protestant district. We tried to deal with the members of that organisation, but not very successfully. Seamus Timoney got a couple of them one day.”13

Three of those killed by the IRA were nationalist civilians: Daniel Rogan, a bystander shot dead in the course of the killing of police “murder gang” member Sergeant Christy Clarke on the Falls Road on 13th March 1922.14 Samuel Mullan was the only nationalist killed for suspected informing during the Pogrom – on 29th March 1922, he was abducted from a queue of expelled shipyard workers receiving relief from the White Cross Organisation at the Hibernian Hall on the Falls Road; his body was found shortly afterwards on the nearby Whiterock Road.15

Edward Devine was the managing director of Hughes Bakery on the Springfield Road; he was killed in the course of an armed robbery of the business on 12th June 1922, an action attributed to the Executive (anti-Treaty) faction of the IRA. This killing so disgusted James Farron that he resigned from the IRA: “It was not a job – it was a murder … That was Mr Devine. It was a hold-up job and should not be done at all and the man happened to lose his life.”16

Killings by the British military

In his landmark history, Northern Ireland – The Orange State, Michael Farrell described the British army as behaving “with fine impartiality” at the outset of the Pogrom.17 This pithy assessment was expanded on by O’Halpin and Ó Corráin, who said:

“It is clear that in Belfast the military did not generally distinguish between contending groups of rioters or curfew breakers on political lines: they would fire impartially on crowds failing to disperse, or on curfew breakers or on anyone who failed to halt when ordered to do so, or in response to fire aimed at them.”18

Over the course of the Pogrom, British troops killed 51 people, 20 nationalists and 31 unionists. The former included three IRA members, while the latter included one British soldier, killed when he walked across a comrade’s line of fire, and one Special Constable, shot in March 1922 as he attempted to escape having been arrested by a military patrol in the city centre.19

British troops man a makeshift barricade

All but eight of the killings by British troops took place before the end of the watershed month of November 1921, after which the Unionist government relied more heavily on the re-mobilised and expanded Specials. Thirty-nine of these 43 killings happened during rioting (the other four were curfew-related), illustrating the degree to which the authorities turned to the British military to quell such disturbances in this period.

Apart from the Special Constable shot attempting to escape, the remainder of the eight killings by British military in 1922 involved two loyalist combatants killed in action and five more people killed during rioting.

Although O’Halpin and Ó Corráin argue that the fog of war obscures responsibility for killings during rioting, we know that British troops killed these people – because they said they did. From evidence given by military witnesses to inquests held by the City Coroner, it is even possible to pinpoint which units of the British Army were responsible for many of these killings and to see in which areas of the city they were in action at various times.

For example, the 2nd Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment killed two men in Sandy Row and Bankmore St in south Belfast on 30th and 31st August 1920.20 The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry killed three civilians during rioting in Ballymacarrett in the east of the city on 25th and 28th August 1920.21 A month later, on 29th September, they were called out to deal with rioting on the Falls Road on the other side of the city, where they killed four men.22

British armoured car in Foundry St, Ballymacarrett (Illustrated London News, 1st September 1920)

The 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment was responsible for killing 20 of the 51 people killed by British troops. Sub-units of this formation were called out to suppress rioting in both Clonard and Ballymacarrett during the first two days of the Pogrom, where they killed 14.23 In mid-October of the same year, they were sent to the ‘Bone area of north Belfast to deal with rioting – there, they shot dead two Protestants and ran over another with a military lorry.24

The Norfolks remained in Belfast until at least the spring of 1922; relations between them and the unionist community in general and the RIC and Specials in particular were fractious, possibly due to the fact that during their time in the city, they killed five nationalists but 15 unionists. The hostility of unionists to the Norfolks was so entrenched that the nationalist Irish News ran a satirical article in March 1922, giving a tongue-in-cheek explanation for this:

“It concerned his Majesty’s Norfolk Regiment: it was to the effect that all the soldiers in the regiment are Roman Catholics and that all the officers and non-commissioned officers are Jesuits in disguise … The proposition can be demonstrated with the mathematical precision of an Euclidean formula: (1) The Duke of Norfolk is notoriously a Roman Catholic. (2) He is called the Duke of Norfolk because all Norfolk County belongs to him. (3) The R.C. Duke of Norfolk tolerates no one on his property but R.C.s. (4) Soldiers of the Norfolk Regiment come from Norfolk: therefore they are Roman Catholics.”25

Tim Wilson has argued convincingly that unionist rage against the Norfolks was borne out of the fact that they were seen as being – to return to Farrell’s formulation – too impartial:

“In attempting to implement a relatively even-handed policy of suppressing sniping from whichever side seemed to offer the most urgent threat at the time, the Norfolks fundamentally offended popular loyalist perceptions of where the responsibility for the conflict lay. The Norfolks refused to project the guilt unilaterally onto the Catholic areas. In doing so, and in opposing Protestant communal defenders, they challenged the basic loyalist understanding of the conflict in which they found themselves.”26

Killings by the police and Specials

As the Special Constabulary, particularly the A Specials, worked alongside the regular RIC and later the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), killings by police and Specials are grouped together here. However, these killings can be divided into two types: those done on duty while acting in an official capacity – although not always acting within the law – and those for which the unofficial police “murder gang” was responsible.

Thirty-five people were killed by regular police and Specials acting officially – as with killings by British military, this figure is primarily based on testimony given to the City Coroner’s inquests. The figure includes seven IRA members and one loyalist combatant killed in action.27

Given that the sub-total of 35 is skewed by killings carried out by the notoriously sectarian Specials, it is somewhat surprising that of the 27 civilians, 16 were nationalist and 11 unionist, suggesting that the regular police also behaved with a degree of impartiality.

Two of the 11 unionist civilians were shot dead for curfew violations, eight were killed during rioting. The latter included John Lawther and Frederick Blair, both killed on 28th September 1920 in the ‘Bone – although the inquest jury for Blair’s death did not attribute responsibility, the Irish News carried a detailed description of the rioting, highlighting the role of Head Constable Clarke in confronting loyalist rioters: “It is the police you are shooting at. Cease fire or I will be compelled to order my men to fire.”28 On 17th December 1921, John McMeekin was shot dead by police who arrived at the scene of a forcible eviction in Clermont Lane in Ballymacarrett, where furniture was being burned in the street.29

The eleventh unionist civilian killed represents an exceptional case. In a previous blog post, the killing of George Walker during an Orange parade was attributed to a nationalist sniper firing indiscriminately at the march. However, subsequent research has revealed that Walker was actually killed by a B Special:

“There was an Orange procession that day in Percy Street and a ‘B’ Class Special named Billy Haddock of the Shankill Road Barracks was in the procession. He was on the outskirts of it by way of protecting the mob. A man named Black [sic] was standing at the lamp post. Haddock mistaking this man for a Sinn Feiner went up to him, put the muzzle of his revolver to his mouth and mortally wounded him … The mob of Orangemen then tried to lynch Haddock who was rescued with much difficulty … District Inspector Nixon arrived on the scene … and released Haddock.”30

Unusually, both Nixon and another District Inspector, Deignan, attended the inquest. Neither mentioned the central involvement of Special Constable Haddock. However, the episode does give chilling insights into both the Specials’ modus operandi for dealing with “Sinn Feiners”, meaning nationalists, and the degree to which senior police officers viewed this approach as acceptable.31

Three nationalists were killed by the regular RIC during rioting, but four others were killed at close range by police – two of these were revenge killings in Dock St by Specials in retaliation for the earlier killing of a colleague in the same street. Eight civilians were killed during outbreaks of unselective shooting into nationalist areas by police and/or Specials. Finally, on 19th April 1922, Francis Hobbs was shot dead by a sniper in Thompson St in Ballymacarrett – this killing is attributed to the Specials, as a witness at the inquest reported that the fatal shot was fired by one of a group of men wearing armlets, a common form of identification issued to non-uniformed C Specials.32

C Specials on duty on Albertbridge Rd in Ballymacarrett

Apart from the killings by police and Specials acting officially, a further 20 nationalists were killed by the RIC “murder gang,” five members of the IRA and 15 civilians.

These killings are attributed to this group of police officers because, in every case, they left behind witnesses – wives, mothers, siblings, a landlady or a grandson. The terror that the “murder gang” intended to instil among nationalists would be deepened if the families could spread the word of what had been done to their loved ones and by whom.

For this reason, rather than any sense of chivalry, Eliza McMahon, her daughter Lily and niece Mary Downey lived to tell the tale of what happened to their family in Kinnaird Terrace on the night of 23rd/24th March 1922 – the RIC City Commissioner noted that, “Mrs McMahon and Neice [sic] who were in the house at the time states [sic] that four of the men wore police uniform and the fifth a Burberry coat.”33

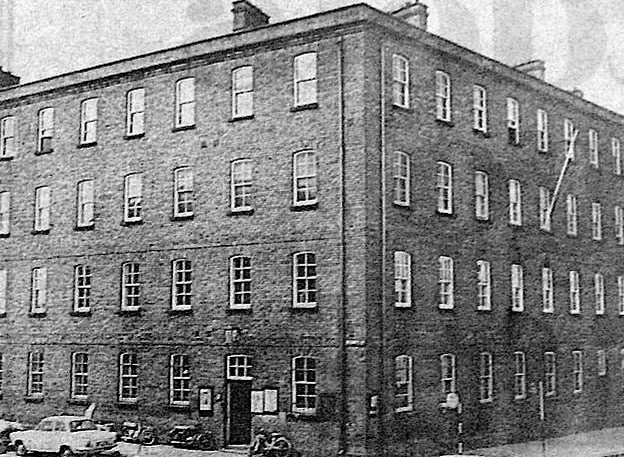

After the Arnon St killings, the widow of Joseph Walsh was asked to attend an identity parade in Brown Square RIC Barracks to pick out those responsible, but when she got there, the police refused to take part:

“When it was not held she left and when coming out of the barracks a group of policemen amongst whom was Const. Gordon were standing at the door. She pointed to Gordon and said ‘there’s the man who murdered my husband.’ The group immediately threw her out of the barracks and it is alleged kicked her out.”34

On occasion, police would return to the scene of “murder gang” killings to inflict further hurt on the bereaved. After the killing of the Duffin brothers in April 1921, District Inspector Ferris – himself implicated in the March 1920 killing of Cork Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain – called to the house to collect a dog which had been found at the scene, a detail noted by the Irish News which, under the pointed headline “Who owned the dog?”, said that “the inference is that it accompanied the men who shot the brothers.”35 The morning after Alexander McBride was abducted and killed in June 1921, “[District Inspector] Nixon called on Mrs McBride to express his sorrow at the death of her husband and she recognised him as the person in charge of the party who had taken him away the previous night.”36

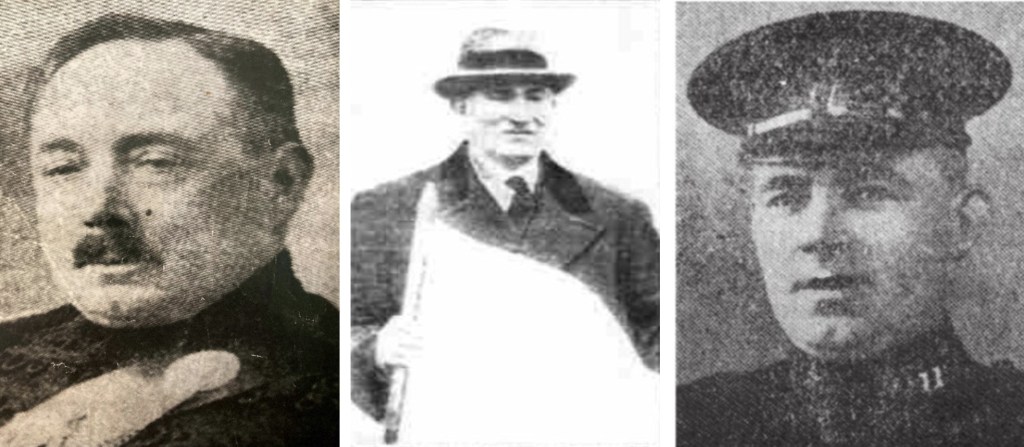

Members of the RIC “murder gang”: District Inspector John Nixon, Sergeant Christy Clarke, Constable James Glover

Killings by unspecified loyalists

There were 118 people who were killed by loyalists, but it is not possible to state with any certainty which specific organisation killed them. There are a couple of reasons for this.

The first is that there was a plethora of loyalist paramilitary groups operating in Belfast. The oldest was the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), which had been officially disbanded in May 1919; an attempt was made to re-establish it in June 1920 but this appears to have largely fallen flat – although the pre-Great War UVF’s arms were still in circulation.37 Among the newcomers was the Ulster Protestant Association (UPA), which was founded in August 1920 but “had become by 1922 an efficiently organised gang ‘of the lowest and least desirable of the Protestant hooligan element’, dedicated to the extermination of Catholics by any and every means.”38 The most numerous was the Ulster Imperial Guards, also founded in August 1920 and, by November 1921, capable of bringing thousands of members onto the streets in a show of strength.39 In May 1921, one-time UVF Larne gun-runner Fred Crawford established his own armed grouping called the Ulster Brotherhood – more colloquially known as “Crawford’s Tigers” – membership of which required swearing an oath “to destroy and wipe out from Ulster by every means in my power the foul Sinn Fein conspiracy of murder, assassination and outrage.”40

The second problem is that there were significant overlaps in membership between these loyalist paramilitaries and the Special Constabulary, particularly the C1 Specials, which were rapidly expanded in early 1922 by the simple expedient of swearing in members of those paramilitaries.41

An example of this was Alex “Buck Alec” Robinson – his story can be viewed as an extreme case study, or the case study of an extremist, or both. Brought up just off York St in north Belfast, “Despite his lengthy criminal record, Robinson joined the C1 section … His membership of the UPA also testified to his aggressiveness.”42 By late 1922, the UPA and other loyalist paramilitaries had outlived their usefulness to the Unionist government and in October of that year, Robinson was briefly interned; his internment file reveals what the RUC believed he had done:

“Buck Alec” Robinson

“He was alleged to have thrown ‘a bomb off a tram’ towards a group of men, of shooting dead ‘a young fellow named Hughes on the top of a tram car’ and of assassinating a sixty-five-year-old man in a cinema … Police informants claimed that Robinson murdered Catholic neighbour Jane Rafferty in her home, while her Protestant husband was away at sea.”43

Jimmy and Johnny McDermott, both members of the IRA at the time, believed that Robinson was also responsible for killing their father Frank on 19th May 1922 as he returned from work in the Pumping Station on Milewater Road in the docks area.44

The reason it is possible to attribute 118 killings to loyalists, even if it remains impossible to pinpoint which loyalists, is due to the nature of those killings: 68 of them took place at close range, often inside the victims’ own homes or shops, 18 involved unselective bombings or shooting in which the nationalist community was targeted rather than individuals, while 14 involved sniper attacks. The common thread of sectarianism running through these killings clearly points to loyalists as being responsible.

As examples of these various types of killing: on 19th February 1922, John Hunter was asked for a light in Cupar St – when he stopped, he was asked his religion, then shot dead when he answered; Elizabeth McCabe was killed when someone threw a bomb at a crowd of churchgoers making their way into St Matthew’s Catholic church on the Newtownards Road on 23rd April 1922; Michael Crudden was shot dead by a sniper while leaving a confraternity meeting in the Sacred Heart Church on the Oldpark Road on 14th December 1921.45

Assigning precise responsibility for loyalist attacks is further complicated by the fact that these were not all carried out by paramilitaries – for example, in relation to snipers, a sympathetic RIC officer provided a statement to an investigator sent north by the Provisional Government:

“It would be about a month ago on another occasion, I found ‘A’ Special Robinson on the top of Brown Square Barracks sniping into Stanhope Street, a Catholic locality. I brought him down, there were others of the Specials at it several evenings previous … This was done to give the impression to the Police on Peter’s Hill that the Shipyard workers were being fired at from Catholic Quarters. The Specials used [to] fire from the Centre of the top Barrack room … It could not have been done except with the knowledge of DI Nixon and the other police authorities in Brown Square.”46

Brown Square Barracks

For this reason, the category of “unspecified loyalists” includes Specials as well as paramilitaries.

Apart from 99 nationalist civilians, loyalists also killed 16 members of the IRA and Na Fianna – these included Séamus Ledlie, shot dead in Norfolk St between the Falls and Shankill Roads during rioting on 11th July 1921, and Andrew Leonard, shot dead “while protecting those of the same faith as himself” on 13th March 1922 in Townsend St off Divis St.47

Mary Hogg was a unionist woman shot dead at her front door in Fifth St in the Shankill on 11th January 1922; her killers asked for her by name and then accused her, “You are the person who carried information to the Blackstaff Mill.” The location of this killing makes it certain that it was done by loyalists.48

Killings by unspecified nationalists

Just as there were several loyalist paramilitary groups, neither did the IRA have a monopoly of arms on the nationalist side. In fact, republicanism was not the dominant strand within nationalism in Belfast – Sinn Féin was very much in the shadow of the constitutional Nationalist Party, led by Joe Devlin, who was also the Grand Master of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH). As late as June 1921, the RIC City Commissioner estimated that there were 8,000 Hibernians in the city compared to only 900 Sinn Féin members.49

When the Irish Volunteers split in September 1914 over the question of participation in the British war effort, the majority sided with Devlin and John Redmond, leaving to form the Irish National Volunteers, while the remaining minority retained the name Irish Volunteers. The same RIC estimate thought there were 1,300 Irish National Volunteers in Belfast in 1921 as against 500 “Irish Volunteers (Sinn Fein).”50

While the Nationalist Party espoused parliamentary politics, the AOH were no shrinking violets when it came to violence. During the 1918 general election, they battered Sinn Féin election workers and speakers off the Falls Road, contributing to Devlin’s rout of Éamon de Valera at the ballot box. When sectarian conflict erupted in Derry a month before the start of the Belfast Pogrom, they were quick to get involved. John Dillon Nugent, National Secretary of the AOH, reported to the quarterly meeting of the organisation’s governing body that:

“… the order had transferred arms secured by Irish M.P.s before the outbreak of the First World War to some of its members in Derry to defend themselves against ‘the Orange mob’ with ‘forty or fifty rifles … stowed away in the Hibernian hall’. Nugent further claimed to have armed Hibernians in Belfast and detailed how members further south offered refuge to those whose homes were burned in Lisburn.”51

In his BMH statement, McCorley described how the IRA had duped a clergyman into handing over rifles to them which he thought were going to the AOH in Belfast – the implication being that if they had reached their intended recipients, they would have been put to use.52

Uniformed Hibernians in Glenavy, Co. Antrim

In November 1921, the Belfast-born Monaghan TD Seán MacEntee wrote to de Valera, warning him that the Hibernians were in the process of forming a paramilitary organisation of their own:

“I have learned that Mr J.D. Nugent about three weeks ago made a tour of those N.E. Ulster districts, including Belfast, where Hibernianism has a hold, in order to organise a new armed force among the Hibernians to be known as the Hibernian Knights. The ostensible purpose of this organisation, which is being formed on a strictly sectarian basis, is to defend the Catholics against Orange terrorism.”53

It is not clear whether this organisation actually came into being, but the fact that it was planned is telling.

In their statements to the BMH and interviews with Ernie O’Malley for his oral history project, IRA veterans were naturally keen to amplify their own achievements and denigrate the contribution of their bitter political rivals – in this regard, McNally’s comment to O’Malley was typical: “The Hibernians were of no use. Indeed they were a menace through their weakness.” In this way, the Hibernians were consciously excluded from the oral histories that form much of the record of resistance to the Pogrom.54

However, some veterans did acknowledge that ex-servicemen had also assisted in communal defence – McNally commented, “The only men to rely on were the Irish Volunteers and on some of the ex-servicemen.”55 While some ex-servicemen did join the IRA, the majority of them were from the Devlinite side of the 1914 split and remained aloof from the IRA. However, it is further evidence that the IRA did not have a hegemony over defence of nationalists.

Forty-two killings can be attributed to unspecified nationalists, without being able to detail whether these were IRA, Hibernians, ex-servicemen or others. This number is far lower than the comparable figure of 118 killed by unspecified loyalists, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the total of unionists (Crown forces and civilians) killed was considerably less than that of nationalists; secondly, a larger proportion of the unionist fatalities can already be accounted for by the British military or the IRA.

Of the 42, two were Specials, one was a nationalist civilian and the rest were unionist civilians. Twenty-eight of the unionist civilians were killed at close range and it is the circumstances involved – similar in many respects to loyalist killings of nationalists – that allow responsibility to be attributed to nationalists.

James McCormick was asked his religion before being shot dead in Short Strand on 16th February 1922, as was Robert Powell on 21st May 1922 in Edward St behind St Anne’s Cathedral. On 14th April 1922, Matthew Carmichael and a helper were delivering bread on the Crumlin Road when someone grabbed the reins of their horse and led it around the corner where “questions were put to both men” – Carmichael was killed.56

Just as nationalists were targeted in their own homes, so too they targeted unionists in theirs. For example, on 23rd April 1922, two men climbed over the back wall of a yard in Beechfield St in Ballymacarrett and shot Thomas Millar dead through his kitchen window.57

Nationalists also had their snipers: one killed Georgina Campbell in Gertrude St off the Newtownards Road on the evening of 26th May 1922 – at the inquest into her death, there was no mention of there having been any rioting or disturbances in progress at the time.58

Disputed killings

Although there were 180 killings for which the responsibility is unclear, two of those stand out because responsibility was publicly disputed.

On 10th March 1922, while off duty, Lieutenant Edward Bruce of the Seaforth Highlanders was killed at the corner of Alfred St and Ormeau Avenue, between the majority-nationalist Market and majority-unionist Donegall Pass areas. The press on each side was keen to attribute the blame to their political opponents and each side seized on different statements by the Provisional Government to claim that Bruce’s actions had made him a target for those opponents.

The unionist press – including The Times of London – pointed to one statement that Bruce had harassed nationalists on the Falls Road:

“The [Provisional Government] report went on to declare that this officer, who was described as a young man, ordered the removal of a badge of the Fianna (Sinn Fein Boy Scouts), saying ‘Take off that badge of the I.R.A.’ and threatened to make the road run red with blood; that he struck young men in their faces with a riveter’s hammer shaft and declared that he would ‘walk over their bloody corpses yet.’”59

However, this claim was undermined by the fact that the Provisional Government had specified that a Lieutenant Whitelough, also of the Seaforth Highlanders, was involved in this incident.60

Meanwhile, the nationalist Freeman’s Journal in Dublin quoted a different statement that said, “‘The Orange hooligan element in Ballymacarrett had been vowing vengeance against Lieut. Bruce for the past eighteen months. They blamed him principally for the Orange casualties caused by the military in defending Ballymacarrett Catholic Church (St Matthew’s) and Convent.’”61

A fatal flaw in this argument was that Bruce could not have been in charge of the British troops on duty at St Matthew’s in July 1920 – at that time, he was in hospital in London with gonorrhoea.62

However, shortly after this statement was issued, an RIC Sergeant made a statement to a Provisional Government investigator, showing that one Special did have a particular grievance against Bruce:

“About a week before Lieutenant Bruce was murdered he arrested two men at the scene of the shooting outrage in the Urney St. locality. When they were brought to the Barracks they turned out to be two ‘Special’ Constables in plain clothes. One of them had a service revolver but not as is supplied to the police. It was fully loaded. Lieut. Bruce wanted to have the charge preferred against him properly pressed. The police authorities intervened and Headquarters of the Police were rung up. They decided to have him discharged though he had no permit for a revolver. I remember at the time while this matter was undecided the prisoner was looking very vindictively at the Lieutenant.”63

An alternative explanation for where the truth may lie is in the application for a Military Service Pension of Henry Crofton, the Quartermaster of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion and a resident of the Market – he told the assessor that he “Took part in the fighting in the Ormeau Road area in May [sic] ‘22 when Lieutenant Bruce of the British Forces was killed.” If there was skirmishing going on at the edge of the Market, it may well be that a sniper on one side or the other saw a man in civilian clothes at the corner of Alfred St and opened fire.64

The second disputed death was that of Constable George Turner, shot dead on the Old Lodge Road in Carrick Hill on 1st April 1922. All accounts agreed that prior to his killing, the area had been quiet; thereafter, they diverged.

A Special who had been accompanying Turner told the inquest that the fatal shot came from a derelict building at the corner of Stanhope St.65 But according to historian Andrew Boyd, “At an official enquiry later, British soldiers who had been on duty on Old Lodge Road said the shot which killed Turner could not have been fired from any of the Catholic streets.”66

Constable George Turner

Meanwhile, the Provisional Government attributed responsibility for Turner’s killing to the soldiers themselves: “At 10.50 p.m. fire was opened from the Old Lodge Rd. (Unionist) into Stanhope St. and Arnon St. (Nationalist streets), the military on duty in the vicinity returned the fire, and Constable Turner was shot dead.”67 This assertion was probably based on a statutory declaration made by Daniel Girvin, who lived at 11 Stanhope St, who said that “About 10 minutes to 11 on Saturday night 1st April I went to the door and saw a policeman at the corner of Stanhope Street and Old Lodge Road fire up Stanhope Street in the direction of Park Street. The military replied killing that Policeman.”68

Both of these versions of events are plausible.

Summary and conclusions

The people killed by the various combatants during the Pogrom largely reflect those groups’ different roles in the conflict.

The IRA in Belfast embarked on the same War of Independence as the organisation elsewhere in the country – the primary target of that campaign was the RIC, the on-the-ground eyes and ears of the British government, so the IRA killed 18 of the 20 RIC who were killed in the city, including Auxiliaries and Black and Tans; responsibility for the killings of Constable Turner and an RIC Sergeant remains unclear.

As initial defence of nationalist areas against mob attacks then developed into a more explicitly sectarian struggle, the IRA killed 11 more unionist combatants – nine Specials and two other loyalists – as well as 24 civilians, all but three of whom were unionists.

The primary function of the British Army was to deal with rioting when the regular police could not do so. Although the RIC was an armed force, accounts of their attempts to separate rioters, at least in the earliest days, tell of them trying to do so using only their batons and having to return to their barracks to get their carbines – for example:

“He also desired to say that the police throughout the whole of these riots [in Clonard] never fired a shot. They had no arms at all except batons. Any firing that was done was done by civilians, and then there was the response by the military to that fire.”69

When the police’s efforts failed, they called for military support. British troops were specifically trained to shoot people dead and that is exactly what they did, with warnings but without hesitation. They killed 40 civilians (plus one soldier) during rioting, 24 of whom were unionists; they also killed four curfew-violators and six combatants – three IRA, two loyalists and one Special. That combatants only represented a small proportion of those killed by the British military suggests that confronting the IRA was a secondary priority for them – that task fell primarily to others.

The regular police had two roles: the first was to preserve order in a normal policing sense, which in Belfast meant dealing with communal rioting – in doing this, they killed three nationalist and eight unionist civilians. Their second role was to suppress what was viewed as the “Sinn Fein rebellion;” in this regard, they were augmented by the Specials – the regular police and Specials between them killed seven IRA members and one loyalist combatant.

How they went about suppressing the rebellion was more controversial, as it also involved collective retribution meted out to the broader nationalist population – what the Catholic Bishop Joseph McCrory described as “the doctrine of vicarious punishment.”70 As a result, 13 nationalist civilians were killed by regular police and/or Specials acting officially, either at close range, in unselective shootings or by sniper fire.

Those efforts were supplemented by the unofficial police “murder gang,” who killed five IRA members in their homes and 15 nationalist civilians, either at home or having abducted them from their homes.

What have been described here as unspecified loyalist combatants, comprising both paramilitaries and Specials, had one shared task, whether self-assigned or directed by the Unionist government – to crush “Sinn Fein.” Their approach to doing this relied almost entirely on vicarious punishment so their focus was thus directed against nationalist civilians, of whom they killed 99. The 16 members of the IRA and Na Fianna who these loyalists also killed were almost incidental to the civilian fatalities, as they were killed either in the course of, or actively defending against, such attacks.

However, sectarian attacks on civilian opponents were not the sole preserve of loyalist combatants – they were matched in intent and tactics, although not in the number of killings, by unspecified nationalist combatants, who used the same mixture of close-range and sniper attacks, as well as unselective shootings, to kill 38 unionist civilians; they also killed two unionists during rioting, as well as two Specials.

Given that 84% of all those killed during the Pogrom were civilians, it is no surprise that they accounted for the largest percentage of those killed by each of the combatant groups examined.

The IRA might appear to be an exception to this, as “only” 45% of the killings for which it was directly responsible were civilians, but it must be remembered that it also accounted for a proportion of the killings by unspecified nationalists. However, even if all those killings were attributed to the IRA, civilians would still account for a lower percentage of its killings than of any other group, at 67%. This would indicate that it directed its violence against enemy combatants more than other groups did.

The comparable figure for the RIC, RUC and Specials combined is 77%, which includes civilians killed during rioting or for curfew violations. For the police “murder gang,” it was slightly lower at 75%, although after April 1921, they stopped targeting the IRA and instead concentrated solely on killing civilians – IRA member Edward McKinney simply happened to be a lodger of the McMahon family for whom he worked.

Given that its priority was riot control, it is almost remarkable that civilians did not account for more than 86% of those killed by the British military.

The figure for unspecified loyalists is identical, at 86%, while that for unspecified nationalists is highest of all, at 95%. These last two figures jointly illustrate the endpoint of the broad trajectory that the Pogrom took over time: the IRA’s War of Independence led to communal rioting, which was partially suppressed by the RIC and British Army, followed by a low-intensity war between the IRA and the RIC, with a constant potential for sectarian violence to re-ignite.

When the loyalist paramilitaries emerged and the Unionist government re-mobilised the Specials, the conflict then became one in which combatants on both sides were relatively sidelined as targets, because civilian opponents were simply easier to kill. Being outnumbered and outgunned, and with the Specials enjoying political support from the Unionist government and financial support from the British one, it was inevitable that nationalists would fare worst in that outcome.

References

1 Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (London, Yale University Press, 2020), p18-19.

2 Ibid., p19

3 Thomas McNally statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives (MA), WS0410.

4 Roger McCorley statement, BMH, MA, WS0389; Joe Murray statement, BMH, MA, WS0412; Séamus McKenna statement, BMH, MA, WS1016; Statement of Seán Montgomery, Seán O’Mahony papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 44,061/6.

5 Roger McCorley file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), MA, 24SP12076; Séamus Timoney file, MSPC, MA, 24SP12732; Henry Crofton file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF106.

6 Mary Russell file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF24769. The original typescript of the interview states that the factory was in “Chester Street”, but as there was no street of that name in Belfast, it is clear that the MSP clerk mis-heard what Russell said.

7 Paul Cullen file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF55547.

8 Belfast News-Letter, 3rd June 1922.

9 Northern Whig, 7th April 1921; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 15th October 1921.

10 Belfast News-Letter, 1st July 1922.

11 Montgomery statement, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6.

12 Ibid.

13 Tom Fitzpatrick statement, BMH, MA, WS0395. A company of Imperial Guards marched in the funeral cortege of Reid, who had previously lived in the Market, as had Fitzpatrick before he was promoted to O/C Antrim Brigade. Timoney was Fitzpatrick’s replacement as O/C 2nd Battalion and he, too, lived in the Market. The night before Reid’s killing, another Market resident, Annie McNamara, had been killed in a loyalist bomb attack. These overlapping local associations make it very likely that it was Timoney who shot and killed Reid.

14 Northern Whig, 4th April 1922.

15 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 8th April 1922.

16 James Farron file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10867.

17 Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland – The Orange State (London, Pluto Press, 1980), p29.

18 O’Halpin & Ó Corráin, Dead of the Irish Revolution, p19.

19 Joseph Giles and John McCartney – see David Matthews file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF60258; John O’Brien file, MSPC, MA, 2RB109; Private James Jamison – Belfast News-Letter, 3rd September 1920; Special Constable Charles Vokes – Ballymena Observer, 24th March 1922.

20 Belfast News-Letter, 11th September 1920.

21 Belfast News-Letter, 8th & 9th September 1920.

22 Belfast News-Letter, 6th October 1920.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 11th August 1920.

24 Belfast News-Letter, 26th October 1920.

25 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 18th March 1922.

26 Tim Wilson, ‘“The most terrible assassination that has yet stained the name of Belfast”: the McMahon Murders in Context’, in Irish Historical Studies, Volume 37 Issue 145 (May 2010), p83-106.

27 The IRA members were: Frederick Fox, 5th August 1921, MSPC, MA, 1D38; David Morrison, 27th December 1921, MSPC, MA, 1D168; James Morrison, 14th February 1922, MSPC, MA, 1D212; James Magee, 26th March 1922, MSPC, MA, 1D213; John Walker, 20th April 1922, MSPC, MA, 2RB4095; Arthur McCaughey, 31st May 1922, MSPC, MA, DP8007; William Thornton, 20th June 1922, MSPC, MA, 1D127. The loyalist combatant was Thomas Neill, 15th February 1922, Belfast News-Letter, 24th March 1922.

28 Belfast News-Letter, 6th October 1920; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 2nd October 1922.

29 Belfast News-Letter, 27th January 1922.

30 Statement of Constable Michael O’Neill, Craven Street Barracks, 23rd March 1922, Northern Ireland outrages, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), TSCH/3/S11195. Constable O’Neill mis-remembered the victim’s name and the date of the killing but other details in his statement clearly identify the victim as being George Walker, killed on 17th May 1921.

31 Belfast News-Letter, 23rd July 1921.

32 Belfast News-Letter, 1st June 1922.

33 RIC City Commissioner for Belfast to Divisional Commissioner, Occurrences in Belfast 23/3/22, 24th March 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, HA/5/150.

34 “Secret document”, unsigned, 10th April 1922, Stanhope St Murders, 1st April 1922, NAI, NEBB/1/1/5.

35 Irish News, 26th April 1921.

36 Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Ernest Blythe Papers, University College Dublin Archives (UCDA), P24/176.

37 Timothy Bowman, Carson’s Army – The Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910-22 (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007), p182, 192-193.

38 Patrick Buckland, The Factory of Grievances – Devolved Government in Northern Ireland 1921-39 (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 1797), p216.

39 Northern Whig, 14th November 1921.

40 Keith Haines, Fred Crawford – Carson’s Gunrunner (Donaghadee, Ballyhay Books, 2009), p284-286.

41 Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), p75-78.

42 Sean O’Connell, ‘Violence and Social Memory in Twentieth-Century Belfast: Stories of Buck Alec Robinson’, in Journal of British Studies, Volume 53, Issue 3, (July 2014) p734–756.

43 Ibid. Owen Hughes was shot dead on a tram in York St on 3rd March 1922, Belfast News-Letter, 13th April 1922. Peter Mullan was the cinema worker referred to in a previous blog post, shot dead in the Crumlin Road Picture House on 29th August 1922, Belfast Telegraph, 30th August 1922. Jane Rafferty was shot dead in her home in New Andrew St in Sailortown on 17th September 1922, Northern Whig, 7th October 1922.

44 Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001), p232.

45 Northern Whig, 21st April 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 1st June 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 7th January 1922.

46 Statement of Constable Peter Flanagan, Brown Square Barracks, 23rd March 1922, Northern Ireland outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

47 Séamus Ledlie, MSPC, MA, 1D325 & Belfast Telegraph, 9th August 1921; Andrew Leonard, MSPC, MA, 1D398 & Belfast News-Letter, 13th April 1922.

48 Belfast News-Letter, 25th January 1922.

49 City Commissioner’s Monthly Report, June 1921, The National Archives (UK), CO 904/115.

50 Ibid. It should be pointed out that these estimates of numbers had remained identical for months; the City Commissioner’s reports also routinely stated each month that “There has been no intimidation prevalent in the City during the past month,” which at least raises questions over the quality of the RIC’s intelligence.

51 Martin O’Donoghue, ‘Faith and fatherland? The Ancient Order of Hibernians, northern nationalism and the partition of Ireland’ in Irish Historical Studies, Volume 46 Issue 169 (May 2022), p77–100.

52 McCorley statement, BMH, MA, WS0389.

53 Seán MacEntee to Éamonn de Valera, 5th November 1921, Richard Mulcahy Papers, UCDA, P7/A/29

54 Thomas McNally interview, Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, UCDA, P17b/99.

55 Ibid.

56 Northern Whig, 7th April & 6th July 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 13th May 1922.

57 Northern Whig, 3rd June 1922.

58 Belfast News-Letter, 12th July 1922.

59 The Times, 12th March 1922.

60 Tuesday 7th March 1922, Belfast atrocities, NAI, NEBB/1/1/1.

61 Freeman’s Journal, 14th March 1922.

62 https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/bruce/gonnorhea.jpg

63 Statement of Sergeant John Murphy, Springfield Road Barracks, 23rd March 1922, Northern Ireland outrages, NAI, TSCH/3/S11195.

64 Henry Crofton, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF00106.

65 Northern Whig, 4th July 1922.

66 Andrew Boyd, Holy War in Belfast (Belfast, Pretani Press, 1987), p202. Boyd did not provide a reference for this statement, nor have I found one.

67 Sunday Independent, 9th April 1922.

68 Extracts from statutory declarations on Arnon Street and Stanhope Street massacre, NAI, TSCH/3/S1801A.

69 Belfast News-Letter, 12th August 1920.

70 Niall Cunningham, Mapping the Doctrine of Vicarious Punishment: Space, Religion and the Belfast Troubles of 1920–22, paper delivered to European Social Science History Conference at Glasgow University, 14th April 2012.

Leave a comment