Murtagh McAstocker, IRA, killed 24th September 1921; Constable Patrick O’Connor, RIC, killed 10th March 1922

The latest update of The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom established that 501 people died as a result of the political and sectarian violence to which the city was subjected from July 1920 to October 1922. Following on from the review of civilians’ deaths, this post examines how the the killings of combatants varied over the course of that period.

Part 1 can be read here: The changing nature of killings during the Pogrom: Part 1 – civilians

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes.

Introduction

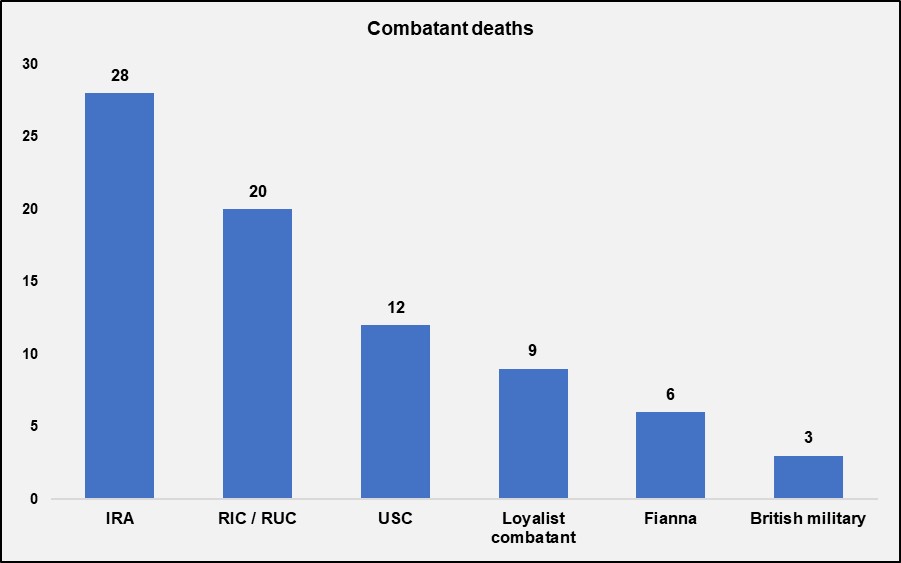

Seventy-eight members of combatant organisations died as a result of the Pogrom: thirty-four of the IRA and its youth wing Na Fianna Éireann, thirty-two regular police and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”), three British military, and nine of the Ulster Imperial Guards or other loyalist groups. The circumstances in which they were killed varied and each of these groups lost at least one member killed when they were not in action.

Killings of IRA members

In 2008, historian Robert Lynch claimed that:

“…despite later tales of the heroic defence of Catholic areas, the IRA did not suffer any notable casualties in defensive operations, which might be expected if members were on the front line as defenders. The fact is that no identifiable IRA members were killed or injured in rioting during the whole two years of the conflict. Those that were killed died largely at the hands of RIC murder gangs: extremist, secret loyalist groups within the police force.”1

Since then, the release of files from the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) have made this statement obsolete, but it was repeated verbatim in his contribution to the Atlas of the Irish Revolution in 2017.2 In fact, of all the combatant organisations in Belfast, the IRA sustained the highest number of fatalities – twenty-six of its members were killed in the city during the Pogrom; two more were killed elsewhere, one in Louth and one in Cavan, while two more died after the Pogrom as a consequence of illnesses they contracted while interned.

Of the twenty-six, five were killed by the RIC’s “murder gang”. Ned Trodden and Seán Gaynor were killed in their homes in revenge for the killing of Constable Thomas Leonard on 25th September 1920.3 Michael Garvey was killed on 26th January 1921 in a case of mistaken identity – a barman also named Garvey was suspected of providing intelligence that led to the IRA’s killing of two policemen in the hotel where he worked; however, the Garvey who was killed was a chemist’s assistant.4

On 23rd April 1921, Dan Duffin was killed in the same attack in which his brother Pat, mentioned in the previous blog post, was also killed.5

Neighbours queue around the block to pay their condolences at the family home after the killing of the Duffin brothers in April 1921 (photo courtesy John Duffin)

Originally from Donegal, Edward McKinney worked as a barman for Owen McMahon and was a lodger in the publican’s house; he was killed in the same attack as his employer and McMahon’s sons.6

However, most IRA fatalities in the city occurred while they were in action.

For example, James Ledlie was killed in the rioting around the Falls Road that followed the Raglan St ambush just before the commencement of the Truce in July 1921.7 Bernard Shanley was shot dead on 16th December 1921 while on picquet duty in Bankmore St, between the majority-nationalist Market and majority-unionist Donegall Pass areas.8 David Morrison was killed defending the Marrowbone or ‘Bone area in north Belfast against a raid by Specials on 27th December 1921.9 On 20th April 1922, John Walker was killed while attempting to repel an attack by Specials and a loyalist mob on the Short Strand.10

The IRA also lost men killed in offensive, as well as defensive, actions. On 5th August 1921, Freddie Fox was killed by a policeman in Earlswood Road in east Belfast – as this was where County Inspector Richard Harrison, founder of the police “murder gang,” lived, the clear implication is that Fox was engaged in either surveillance or – considering he was armed – an attempt to kill Harrison.11 Following the disarming of a group of Specials in Millfield on 31st May 1922, during which one of them was killed, the escaping IRA party was pursued by armoured cars and George McCaughey was “riddled by Lewis gun fire.”12 Three weeks later, William Thornton was killed by Specials in Gloucester St in the Market – he was in the process of setting fire to a business property as part of the arson campaign that formed the latter part of the IRA’s northern offensive.13

Apart from those killed by the “murder gang,” two other IRA members were not in action when killed: Thomas Gray was shot dead in the Earl St pub in which he worked on 6th February 1922.14 The following month, John Dempsey was killed after fleeing to a neighbour’s house when two suspicious strangers knocked on the door of his home in Mountcollyer Avenue off North Queen St.15

The sequence in which IRA members were killed in action roughly correlates to the wider pattern of fatal violence: three during the summer of 1920, six during that of 1921 and the remainder in twos and threes per month in most months from December 1921 onwards.

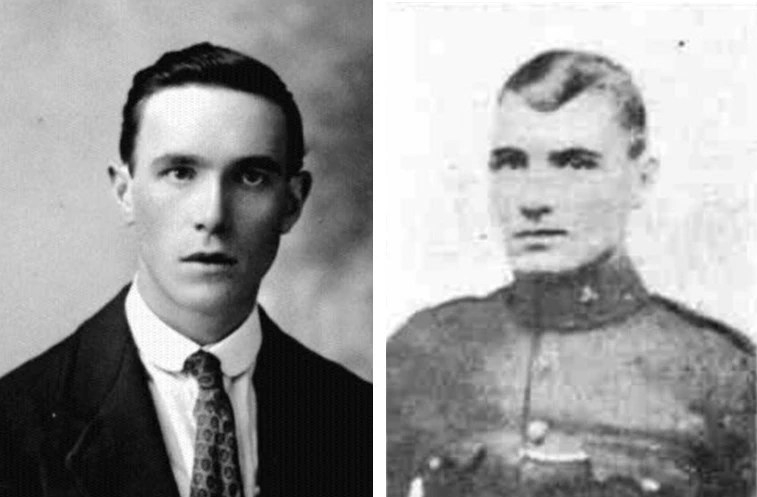

John Dempsey, IRA member killed on 26th March 1922 (photo courtesy Colum O’Rourke)

Killings of regular policemen

There were twenty members of the regular police killed during the Pogrom.

The first was Constable Thomas Leonard, killed at the junction of the Falls Road and Broadway on 25th September 1920 when the IRA attempted to disarm him and a fellow-officer.

“The spot on the Falls Road where Constables Leonard and Carroll were shot” (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 2nd October 1920)

The last was Constable Henry O’Brien, shot dead in the course of an IRA sniping attack on Cullingtree Road Barracks in the Lower Falls on 29th May 1922. The Royal Ulster Constabulary only came into existence three days later, so all the regular policemen killed were actually members of its predecessor, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).16

Not all the policemen killed were based in Belfast and not all were killed on duty. Two came under neither heading: Sligo-based Temporary Cadets John Bailes and Ernest Bolam, members of the Auxiliaries who were on leave in Belfast when spotted in Donegall Place in the city centre on 21st April 1921 and killed by an Active Service Unit of the IRA.17

Before that, the same IRA unit had killed Constables Thomas Heffron and Michael Quinn in Roddy’s Hotel in Oxford St on 26th January 1921 – the two southern-based constables were escorting a fellow-officer who was due to be a witness at the trial in Belfast of an IRA man accused of killing a policeman in Tipperary.18

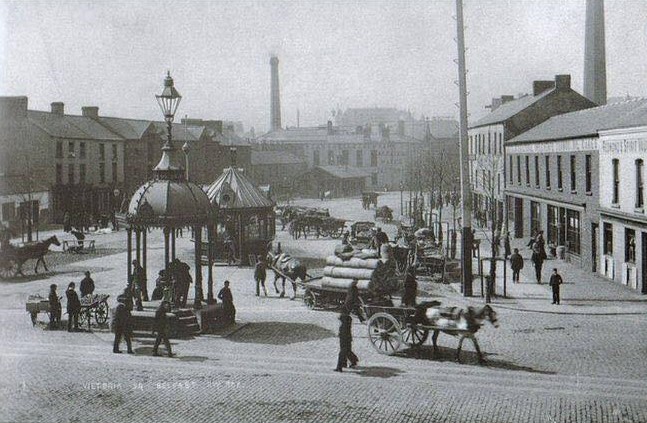

Six weeks later, that IRA unit killed three Black and Tans who had come north to collect lorries and bring them to their depot in Gormanstown, Co. Meath. Constables William Cooper, Robert Crooks and John Mackintosh were shot and killed on 11th March 1921 in Victoria Square in central Belfast.19

Victoria Square, scene of an IRA attack on Black and Tans in March 1921

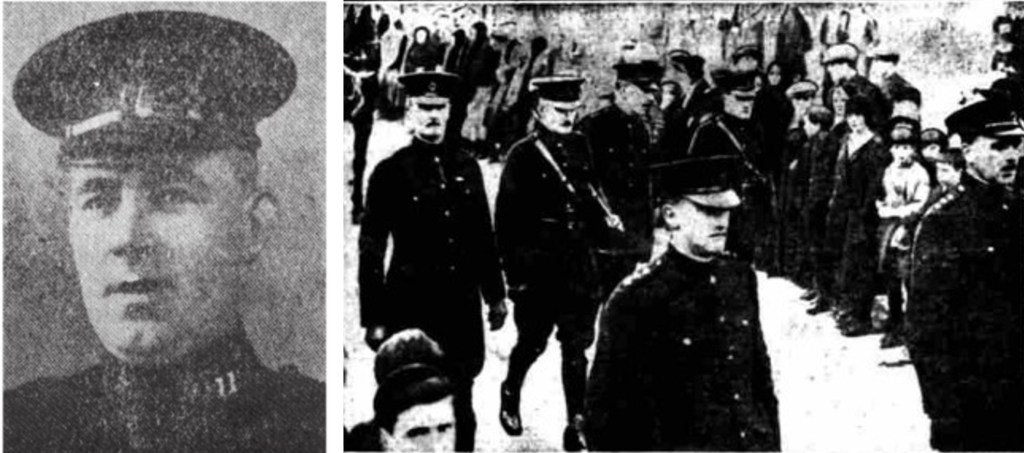

Just as the RIC “murder gang” killed IRA men in retaliation for the killings of policemen, so too the IRA sought to kill RIC men they suspected of being part of the gang. They succeeded in two cases.

Constable James Glover was killed at the end of Cupar St on 10th June 1921. According to Seán Montgomery, “He was shot at the Hibs Hall on the Falls Road. I was talking to one of the men who carried him over to the Royal Victoria Hospital and they kept roughing him to make sure he would die.”20

Another “murder gang” target of the IRA was Sergeant Christy Clarke; Montgomery continued:

“Christy Clarke was wanted by us for his part in the Duffin murders … After the Raglan Street ambush two of the boys were waiting for him to come out of the barrack. He came to the barrack door and took out his watch and waited until after 11 o’clock which was the Truce so he got away once more.” 21

The protracted game of cat-and-mouse came to an end when the IRA eventually caught up with Clarke and shot him dead on the Falls Road on 13th March 1922.

L: Constable James Glover, shot by the IRA as a member of the “murder gang.” R: Funeral procession of Sergeant Christy Clarke; County Inspector Harrison, who the IRA suspected of being a founder of the gang, is on the right of the second row (Belfast Telegraph, 16th March 1922)

Killings of Special Constabulary

There were twelve members of the USC killed on duty during the Pogrom, but with the exception of Special Constable Thomas Sturdy, killed in June 1921, all of them were killed from February 1922 onwards. By this time, the Unionist government, suspicious of the loyalties of many Catholic members of the regular RIC, had re-mobilised and expanded the Specials and viewed them as a more reliable force with which to fight what they viewed as a “Sinn Fein rebellion.”

The most high-profile incident in which Specials were killed was the attack on Special Constables William Chermside and Thomas Cunningham on May St in the Market on 23rd March 1922. The two were on foot patrol when shot by a group of men who had approached them from behind – Chermside died instantly, Cunningham later in hospital.

Later that night, the McMahon family killings took place. The unionist Belfast News-Letter highlighted a connection that was obvious to everyone: “The murder of the two ‘Specials’ at midday on Thursday and the slaughter of the male members of the McMahon household at Kinnaird Terrace yesterday morning are too closely related to admit of dispute; the one horrible crime is the sequel to the other.”22

Police at the junction of May St and Joy St after two Special Constables were killed

A curiosity is that, although it was far from being the most violent area in Belfast, the Market was where four Specials were killed – a third of all the Specials killed in the city. As well as the two mentioned above, Special Constable Nathaniel McCoo was killed during a gun-battle with the IRA in Joy St on 15th April 1922 and Special Constable George Connor was killed in McAuley St on 25th May 1922 after a party of Specials went “to investigate the suspicious movements of a crowd of men who were moving about the end of Montgomery Street.”23

In addition to the twelve killed on duty, there were five other members of the USC killed but the circumstances of their deaths suggest that they should be counted as civilians, as they were all off duty at the time and there is nothing to indicate that they were targeted as Specials. On 15th February 1922, Hugh French was reading a newspaper in his shop on the Old Lodge Road when shots were fired from the lower end of the road, one going through the shop window, killing him; historian Alan Parkinson states that the fatal shot was fired by the RIC.24 On the same day, Hector Stewart was on his way to see his girlfriend when he was shot by a sniper on the New Lodge Road.25 David Fryars was out looking for work when he was shot by an unknown gunman in Thompson St in Ballymacarrett on 26th February 1922.26 Victor Kidd was killed by a sniper on the New Lodge Road while on his way to work in his father’s firm on 26th May 1922.27 Samuel Hayes was home on leave when he was shot dead in a bar on the Newtownards Road on 5th August 1922.28

Killings of other loyalist combatants

There were nine men killed who can be identified as loyalist combatants.

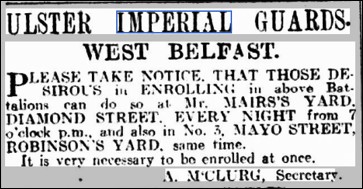

Six were members of the Ulster Imperial Guards, a paramilitary force founded in August 1920 but which first publicly announced its existence by holding a series of church parades on 13th November 1921, in which thousands of members marched.29 The Imperial Guards were themselves born from the Ulster Ex-Servicemen’s Association which recruited heavily among shipyard workers and Robert Boyd was the secretary of both organisations.30

Recruitment ad for Ulster Imperial Guards (Belfast News-Letter, 11th November 1921)

While there are no records of who was in the Imperial Guards, the men’s membership is heavily implied by the presence of detachments from the organisation in all six men’s funeral corteges. For example, while on his way to work in the shipyard, Alex Reid was killed on Cromac St in the Market on 30th November 1921, very likely in retaliation for the killing of Annie McNamara the night before; his funeral procession included “a company of the Ulster Imperial Guard under the command of Sergeant W. J. White.”31

While Reid was killed at close range, three other Imperial Guards were killed by snipers – they may or may not have been in action at the time, but the Guards certainly paraded in their funerals. The first was Andrew James, shot dead in Earl St off York St on 21st November 1921; he was followed two days later by Hubert Phillips, killed in Molyneaux St in the same area; on 8th March 1922, Robert Hazzard was killed by a sniper on York St itself.32

Two Imperial Guards were killed in the course of rioting and while they may simply have been onlookers, it seems unlikely. David Cunningham was killed on 21st November 1921 on the Newtownards Road when the IRA threw a bomb to drive off a crowd of loyalists who were intent on attacking St Matthew’s Church. Shortly afterwards on the same evening, Andrew Patton was shot dead in Central St facing the church. Patton and Cunningham were buried in a joint funeral on 26th November although, curiously, the press report specified only that “behind the remains of Cunningham walked the members of No. 7 Company East Belfast Battalion Ulster Imperial Guards,” rather than the Guards following both men’s coffins; for this reason, Patton is not counted as a member of the Guards, although his widow did thank “the officers and members of the British Legion of Honour, the U.P.A. [Ulster Protestant Association] and Ulster Imperial Guards” in a newspaper small ad inserted some days after the funeral.33

The other Imperial Guard killed during rioting was Walter Pritchard, shot on the Newtownards Road on 17th December 1921.34

Three armed loyalists were definitely killed in action, although there is no evidence to suggest they were necessarily members of the Imperial Guards. On 2nd January 1922, as reported by the Belfast News-Letter, “there was considerable sniping in the direction of military on duty at North Ann St [off Corporation St]. The military returned the fire and here Alexander Turtle was shot dead.” While this account leaves open the suggestion that Turtle may have been an unfortunate bystander hit in the crossfire, the nationalist Irish News was more direct in its framing of the incident: “Inquiries in official quarters elicited the following report on the affair: ‘A soldier was sniped at. He returned the fire and shot the sniper dead.’”35

On 15th February 1922, Thomas Neill was killed when “two snipers were observed on the roof [of a pub in York St]. A police force, arriving on the scene, called on the men to come down and surrender, but they endeavoured to escape by bolting along the slates. Fire was then opened upon them, and one of the snipers staggered and fell into the yard.”36

Robert Dudgeon was killed on 17th May in Cupar St, on the edge of the Clonard area – “a military witness stated that, following shooting in the Kashmir Road district, he saw deceased running with a revolver in his hand. He refused to halt and was shot.”37

Killings of Na Fianna

Six members of Na Fianna Éireann, the republican youth movement, were killed. Although they were notionally unarmed, the lines between Fianna membership and IRA membership were often blurred, with officers in particular sometimes having dual responsibilities. As they were in practice the youth wing of the IRA, they are counted as combatants here.

Possibly a group of Belfast Fianna (photo courtesy John Duffin)

John Murray was one of several residents of the ‘Bone area killed when rioting spread there in late August 1920 – his mother described how “at 1:30a.m. on the 29th August bugles were sounded in their street, and the doors were rapped. The deceased left his house to defend his home…”38

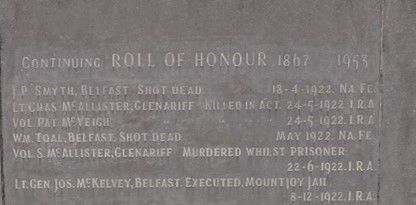

The remaining five Fianna members were all killed in 1922. Thomas Heathwood was carrying despatches when shot dead in Wall St in Carrick Hill on 6th March.39 James Smyth was killed on 18th April in the ‘Bone – newspaper reports said he was standing at the door of his home at 42 Mayfair St when shot; although no MSPC file for him has yet been released, he is commemorated on the Co. Antrim Memorial of republican dead in Milltown Cemetery.40

James Smyth’s name on the Co. Antrim Memorial, Milltown Cemetery

Like Heathwood, William Toal was also killed while carrying despatches – this time during an attack by Specials on the ‘Bone and Ardoyne on 26th May. The address from which his mother applied for a gratuity under the Military Service Pensions scheme in the 1930s was 42 Mayfair St – the identical address at which James Smyth had apparently lived ten years previously; this may be an extreme coincidence or it may point to that address being used by republicans as an organising centre during the Pogrom.41

Leo Rea was killed on 23rd June while crossing Merrion St in the Lower Falls; his mother’s claim for a gratuity was rejected as she was unable to establish that he had been on duty at the time – a report in his MSPC file states that he was shot on his way to work.42 Joseph Hurson was a Lieutenant in the Fianna when killed on 4th July in Unity St in Carrick Hill; his mother’s gratuity claim was rejected on the grounds that she had already received compensation under the British Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Act.43

Killings of British soldiers

Three British soldiers were killed, two while on duty.

Private James Jamison was among a patrol of the 1st Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) confronting loyalist rioters in Linfield Road, off Sandy Row in south Belfast, on 31st August 1920. He was killed when he walked across the line of fire of a fellow-soldier who was shooting at the rioters.44

On 2nd January 1922, an hour after the loyalist sniper Alexander Turtle had been killed while firing at British troops, Private Ernest Barnes of the 1st Battalion Norfolk Regiment was killed in Sussex St, only a few hundred yards away; the Irish News was keen to link the two killings, stating that Barnes was shot by a man with a rifle who emerged from “Dale Street, a notorious Orange quarter.”45

In response to the killing of Private Barnes, the commanding officer of the Norfolks announced that the regimental band would no longer perform in public – a rather underwhelming response to the death of one of the men under his command.46

A British military post in Henry St, a short distance from where Private Barnes was killed

Just over two months later, on 10th March, Lieutenant Edward Bruce of the 1st Battalion Seaforth Highlanders was killed in what remains one of the most puzzling killings during the Pogrom. All that can be established beyond dispute is that he, along with some fellow-officers, had attended the Opera House in Great Victoria St that evening. Afterwards, according to the nationalist press, he walked a sister-in-law of one of the officers home to Joy St in the Market, although according to one of the other officers, “deceased was alone when we left him at the Opera House.”47

Bruce was billeted at the War Hospital on the Grosvenor Road but Joy St and the Market lay in the complete opposite direction from the most natural route that would take him from the Opera House back to his quarters. However, the other officer did say they had arranged to meet Bruce later at “the Club” – possibly the Belfast Sailors’ & Soldiers’ Service Club, but if so, that was in Waring St, which lay in a third direction from the Opera House and getting there did not involve walking via the Market.

What was not disputed was that Bruce was not seen again until after shots were heard in the vicinity of Ormeau Avenue at the southern edge of the Market. District Inspector Lewis of the RIC was in the vicinity and made his way there: “‘I found the poor fellow on the footpath at the corner of Alfred Street … I made an examination of the body and realised that there was no hope.’”48

In the aftermath of the killing, the press on both sides was keen to attribute blame for the killing to their political opponents. This will be re-visited when the question of responsibility for the killings in Belfast is explored.

Summary and conclusions

Of the 423 civilians killed during the Pogrom, 59% were nationalists and 41% unionists. However, the seventy-eight fatalities among combatants were split differently, with thirty-five members of the Crown forces killed compared to thirty-four republicans, while the addition of nine loyalist paramilitaries means that the majority of combatants killed were actually from among those fighting to maintain the Union.

The IRA had the heaviest losses of any combatant organisation, with twenty-eight fatalities. As it was the instigator of the War of Independence, against which unionism reacted violently, this is perhaps not surprising. The IRA members who died did so in a variety of settings: sixteen in defensive actions, three in offensive operations, five at the hands of the “murder gang”, two while at work or at home and two as a result of internment.

Five members of Na Fianna were killed in action, all of them in what could be described as defensive operations in which they were assisting the IRA. This, taken in conjunction with the preponderance of IRA fatalities suffered in similar operations, illustrates the extent to which communal defence became republican forces’ main priority. They might have preferred to follow a different agenda, but apart from the isolated attacks on southern-based Auxiliaries or Black and Tans and the doomed northern offensive, the situation on the ground dictated that defence took precedence. However, in view of the numbers of fatalities suffered by Belfast nationalists in general, whether this was a successful defence is more debateable.

Most of the twenty RIC officers killed can be split into two groups: nine who were specifically targeted by the IRA – this includes the seven southern-based men and two “murder gang” members – and an equal number who just happened to be the constables present when the IRA chose to mount an attack in a particular location. One of the two RIC outliers was Sergeant John Bruin, killed by unknown assailants in a pub on York St in April 1922.49 The other outlier was Constable George Turner, whose killing on 1st April 1922, like that of Lieutenant Bruce, can be debated in terms of responsibility.

A dozen Specials were killed on duty with, as noted above, a third of those killings happening in the Market area. The fact that all but one of the twelve were killed during 1922 reflects the greater reliance the Unionist government placed on the Specials after November 1921 as their preferred front-line defenders against republicanism.

The most striking thing about British military fatalities is how few of them there were – only two soldiers were killed on duty. This suggests that while the local combatants had few compunctions about inflicting fatal violence on each other or on the others’ communities, they were far more circumspect when it came to attacking the British Army.

The next blog post will examine who was responsible for the killings during the Pogrom.

References

1 Robert Lynch, ‘The People’s Protectors? The Irish Republican Army and the “Belfast Pogrom,” 1920–1922’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 47, No. 2 (April 2008), p381.

2 Robert Lynch, ‘Belfast’, in John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy & John Borgonovo (eds), Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork University Press, Cork, 2017), p631.

3 Edward Trodden file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives (MA), 1D153.

4 Michael Garvey file, MSPC, MA, DP376; Northern Whig, 25th March 1921; in relation to the mistaken-identity aspect of this killing, see Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Blythe Papers, University College Dublin Archives, P24/176.

5 Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Beyond the Pale Publications, Belfast, 2001),, p76-77.

6 McKinney was named as an IRA Volunteer in Statement of Seán Montgomery, Seán O’Mahony papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 44,061/6.

7 James Ledlie file, MSPC, MA, 1D325; Belfast Telegraph, 9th August 1921.

8 Bernard Shanley file, MSPC, MA, 1D145; Belfast News-Letter, 7th January 1922.

9 David Morrison file, MSPC, MA, 1D168; Belfast News-Letter, 11th January 1922..

10 John Walker file, MSPC, MA, 2RB4095; Belfast News-Letter, 1st June 1922.

11 Frederick Fox file, MSPC, MA, 1D38; Belfast Telegraph, 30th August 1921.

12 George McCaughey file, MSPC, MA, DP8007.

13 William Thornton file, MSPC, MA, 1D127; Belfast News-Letter, 1st July 1922.

14 Thomas Gray file, MSPC, MA, 1D127; Northern Whig, 2nd March 1922.

15 Northern Whig, 29th April 1922.

16 Belfast News-Letter, 7th July 1922.

17 Montgomery statement, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6.

18 Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), MA, WS0389; Séamus McKenna statement, BMH, MA, WS1016; Joe Murray statement, BMH, MA, WS0412.

19 Northern Whig, 7th April 1921.

20 Montgomery statement, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6; Belfast News-Letter, 2nd September 1921.

21 Montgomery statement, O’Mahony papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6; Northern Whig, 21st April 1922.

22 Belfast News-Letter, 27th March 1922.

23 Northern Whig, 14th June 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 26th May 1922.

24 Northern Whig, 16th February 1922; for the police-bullet theory, see Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2004), p226.

25 Northern Whig, 23rd March 1922.

26 Belfast News-Letter, 29th March 1922.

27 Belfast News-Letter, 23rd June 1922.

28 Northern Whig, 6th September 1922.

29 Northern Whig, 14th November 1921.

30 Timothy Bowman, Carson’s Army – The Ulster Volunteer Force 1910-22 (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2007), p196.

31 Belfast News-Letter, 5th December 1921.

32 Belfast News-Letter, 5th January 1922; Northern Whig, 5th April 1922.

33 Northern Whig, 16th February 1922 (Cunningham inquest); Belfast News-Letter, 19th January 1922 (Patton inquest); Northern Whig, 28th November 1921 (funeral); Belfast Telegraph, 3rd December 1921 (widow’s small ad).

34 Northern Whig, 16th February 1922.

35 Belfast News-Letter, 3rd January 1922; Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 14th January 1922.

36 Belfast News-Letter, 16th February 1922.

37 Belfast News-Letter, 29th June 1922.

38 John Murray file, MSPC, MA, 2RBSD107; Belfast News-Letter, 9th September 1920.

39 Thomas Heathwood file, MSPC, MA, DP4309; Belfast News-Letter, 13th April 1922.

40 Belfast News-Letter, 2nd June 1922.

41 William Toal file, MSPC, MA, DP6722; Northern Whig, 21st June 1922.

42 Leo Rea file, MSPC, MA, 2D504; Belfast News-Letter, 8th July 1922.

43 Joseph Hurson file, MSPC, MA, 2D502; Northern Whig, 21st July 1922.

44 Belfast News-Letter, 3rd September 1920.

45 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 14th January 1922.

46 Ibid.

47 Irish News, 13th March 1922; https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/bruce/inquiry/inquiry.html

48 Belfast Telegraph, 11th March 1922.

49 Northern Whig, 10th June 1922.

Leave a comment