The latest update of The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom established that 501 people died as a result of the political and sectarian violence to which the city was subjected from July 1920 to October 1922. This blog post examines how the nature of the killings changed over the course of that period.

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes.

Introduction

Writing in 2022, historian Tim Wilson noted that:

“… the Great War had militarised the business of crowd control. Rioting was now routinely suppressed using automatic weaponry … Such tactics help explain why the massive set-piece rioting of July and August 1920 was not repeated. Street disturbances did not disappear in Belfast, but they do seem to have become smaller.”1

To what extent is this observation correct?

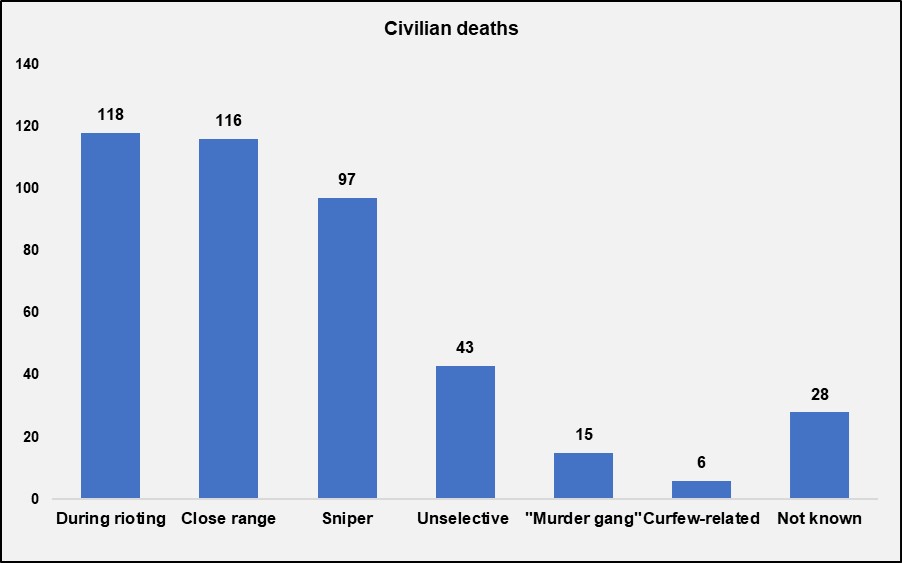

84% of those killed during the Pogrom were civilians, not members of any combatant organisation, whether republican, loyalist or the forces of the state. The killings of these 423 civilians can be broken down under several headings:

- People killed during rioting

- People killed at close range

- People killed at longer range by snipers

- People killed as a result of sectarian violence directed generally at members of one or other community – these can be termed “unselective” as the targets were not individually chosen

- Men and boys killed by members of what became known to nationalists as the police “murder gang” – members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) who avenged killings of policemen by killing members of the nationalist community; some of their victims were members of the IRA, the majority were not

- Killings that were related to breaches of the curfew

- A final group labelled “Not known” – these are killings for which no inquest report could be found or where an inquest was held, the circumstances of the killings remained unclear

Each of these headings will be examined in turn, as will the changes over time in the mixture of the different types of killings.

Apart from civilians, seventy-eight members of combatant organisations also died: thirty-two members of the police and Specials, three British military, thirty-four of the IRA or its youth wing Na Fianna Éireann, and nine of the Imperial Guards or other loyalist organisations. The circumstances in which they were killed also varied; remarkably, every one of these groups lost at least one member killed when they were not in action.

Killings during rioting

As can be seen from the graph above, killings during rioting were – by a tiny margin – the most numerous type of fatality suffered by civilians.

They were also by far the most dominant form of killing during the first sixteen months of the Pogrom, up to the watershed month of November 1921, when the Specials were re-mobilised and placed under the direct control of the Unionist government, having previously being stood down under the terms of the Truce of July 1921. In this initial phase, the 90 killings during rioting accounted for two-thirds of all civilian deaths.

Clonard Monastery, in which Br Michael Morgan was killed

Not everyone killed during rioting was necessarily engaged in rioting at the time. On 22nd July 1920, a lay brother, Michael Morgan, looked out of a window in Clonard Monastery to observe the violence which was then engulfing the surrounding area; as he did so, he was hit by a burst of fire from British troops who were attempting to disperse the rioters. The following night, soldiers fired a volley over the heads of rioters attacking St Matthew’s Catholic Church on the Newtownards Road; half a mile away on the corner of Welland St, Mary Ann Weston was killed by a stray bullet from that volley.2

Rioters at an unspecified street corner, Illustrated London News, 10th September 1921

The deaths during rioting mainly occurred in two surges which coincided with the general waves of killings: 50 during the initial outbreak of the Pogrom from July to September 1920, 28 during the corresponding period of 1921.

There were 28 further killings during rioting after November 1921, but in this second phase of the Pogrom, they were numbered in a few per month, rather than the dozens during the initial phase. This bears out Wilson’s observation – by November 1921, people in Belfast had found new ways to kill each other.

Killings at close range

In the course of an IRA attack with revolvers on three Black and Tans in Victoria Square in Belfast’s city centre on 13th March 1921, a bystander, Alexander Allen, was shot dead. He became the first civilian to be killed at close range. Two months later, a Harbour Constable, Alfred Craig was killed in the course of a scuffle with three men at the gate to the city’s docks.3

However, close-range killings only became an established part of the repertoire of killings in Belfast the following month. At about 9:30pm on 11th June 1921, Special Constable Thomas Sturdy became the first member of the Specials to be killed in Belfast when he was shot dead at the corner of Dock Lane and North Thomas St in the majority-nationalist Sailortown district. Half an hour later, in an apparent revenge killing, Specials broke into the home of Patrick Mulligan in Dock Lane, chased him into the back yard of his house and shot him there at point-blank range. A quarter of an hour after that, a group of four Specials dragged Joseph Millar out of his house, also in Dock Lane – that was the last time he was seen alive.4

After November 1921, there were 28 killings during rioting but they were eclipsed in magnitude by 110 killings at close range in the same period.

The latter took place in various locations. Some people were killed in their own homes, such as Michael Hutton, shot dead by intruders as he sat reading by his kitchen fire in Central St, Ballymacarrett on 24th February 1922. Some were killed on trams, such as James Donaghy and Samuel McPeake, both killed on the same tram as it travelled down the Crumlin Road on 15th June 1922.5

Workplaces were a fruitful source of victims for killers. The licensed trade, in terms of both pubs and spirit-groceries, was known to be one of the few in Belfast dominated by Catholics – from November 1921 to February 1922, there was a spate of killings in which eight men were killed in such premises. However, the same gunmen who killed John Kelly in his spirit-grocery on Ohio St off the Crumlin Road on 24th November 1921 also killed his next-door neighbour who was in the shop at the time, Thomas Thompson, a Protestant.6

Similar “mistakes” could be avoided by the simple expedient of asking people their religion. When a group of IRA men entered a cooper’s yard in Little Patrick St off York St on 19th May, they did this – the only Catholic worker was let go after which the four Protestants were shot, killing three of them. The following day, in nearby Henry St, “two armed men came into the yard of Messrs. J. P. Corry & Co. … asked witness his religion and he answered ‘Protestant.’ They then questioned [John] Connolly and another workman, and the witness, knowing the men’s intentions, said ‘They’re both Protestants.’ The men, however, fired point-blank at Connolly, not giving the unfortunate man a chance to reply.” Connolly’s workmate had been unable to save him.7

Gender was no deterrent. On 17th December 1921, Frances Donnelly was shot dead in her shop on the Castlereagh Road; the same fate met Margaret Page, killed in her North Queen St shop on 11th February 1922.8

Nor did age offer any protection. Peter Mullan was a 65-year-old who worked as an usher in the Crumlin Road Picture House. On the night of 29th August 1922, he was at work when the darkened cinema was lit up by the flashes of revolver shots – Mullan died instantly. By a grim irony, the film showing at the time was called “Danger.”9

The former Crumlin Road Picture House

Sniper attacks

By the summer of 1921, non-state elements on both sides were better armed with rifles than they had been at the initial outbreak of violence. As well as having access to the arms imported during the Home Rule Crisis by the Ulster Volunteer Force, loyalists who were members of the Specials were allowed bring their weapons home with them.

Meanwhile, the IRA stole weapons from loyalists: “On the morning of the Truce 1921, one of my I/Os [Intelligence Officers] reported wholesale transfers of arms from Specials’ Barracks to unofficial dumps. In one of these cases, in company with another man, I lifted five rifles from a dump on Ballysillan Road.”10

They also acquired rifles under false pretences from the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), as outlined by Roger McCorley, later the O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade:

“… we had got information through our Intelligence that a Catholic clergyman outside Belfast had sixty Martini-Enfield rifles which had been the property of the old National Volunteers who were no longer in existence. He had sent information into Belfast to the Hibernian element that he had these arms and he asked them to call out and collect them for use in the defence of the nationalist areas. The information from our Intelligence Department was such that we were able to call out at the appropriate time and collect these arms ourselves. The clergyman instructed our man, he being under the impression that we were of the Hibernian element, that under no circumstances were these arms to get into the hands of the IRA. Our people assured him that they would make sure no one would get control of the arms other than themselves.”11

They even bought weapons from a loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Protestant Association, using a Presbyterian IRA member, Charlie Stewart, as the go-between to avoid arousing suspicion: “I was working in the shipyard and I was engaged in the securing of arms … I was engaged in the purchase of arms that time up to the Truce … We got four rifles from the shipyard.”12

Thus armed, both sides could use their rifles, not simply to deter threatening mobs from the other side by keeping them at a distance, but also to launch attacks on members of the opposing community.

On 14th June 1921, a twelve-year-old Protestant boy, William Frazer, was walking along Ashmore St on the border between the unionist Shankill and nationalist Clonard areas when he was shot by a sniper. A passer-by, Hugh McAree, “rushed on to the road to help the little boy Frazer. He was shot by some person who was spotting. As far as witness knew, the shots came from the back of the houses and from the Falls Road direction.” McAree was a Catholic.13

Robert Walsh was unlikely to have been the intended victim of the sniper who killed him on the morning of 2nd April 1922 in Arnon St in Carrick Hill – he was an eight-month-old baby in the arms of a neighbour at the time. She was probably minding him while his parents paid their condolences to another Walsh family of the same street to whom they were related – his uncle was one of those killed the night before in the “Arnon Street killings.”14

Eighteen civilians were killed by snipers in the summer of 1921, but like close-range killings, deaths at the hands of snipers became much more prevalent from November 1921 onwards, when a further 79 were killed in this way, also surpassing the 28 killed during rioting in the same period.

Unselective shootings and bombings

Unlike close-range killings and sniper attacks, where particular targets were selected, both sides also carried out attacks that were generalised or unselective in the sense that they were aimed indiscriminately at the opposing side – the intention was to kill someone, anyone, rather than a particular individual.

The first victim of such a killing was George Walker, killed on 17th May 1921 in Beverley St between the Falls and Shankill Roads when nationalists opened fire on an Orange procession that had come from Agnes St.15

Within weeks, the police had adopted the new tactic of indiscriminate shooting. On 14th June 1921, Kathleen Collins was shot dead in Cupar St off the Falls Road when Specials, returning from the funeral of Special Constable Sturdy in the City Cemetery on the Falls, began randomly shooting up nationalist areas.16

The following month, following the IRA killing of an RIC Constable in an ambush, the police and Specials mounted a general attack on the Lower Falls, in which five people were killed. The usual pre-Twelfth tension had already been compounded by the ambush, but “It was rendered infinitely worse by the actions of the Crown forces in careering along the streets, firing in all directions.”17

Five civilians were killed, including thirteen-year-old Mary McGowan – at the inquest into her death, an eye-witness “… explained that the armoured car was of the cage type and contained ‘Specials.’ The occupants indulged in what he described as wild and indiscriminate firing.” Not alone did the inquest jury find the Specials responsible for her death, “They added a rider that in the interests of peace the Special Constabulary should not be allowed into localities occupied by people of opposite denominations.”18

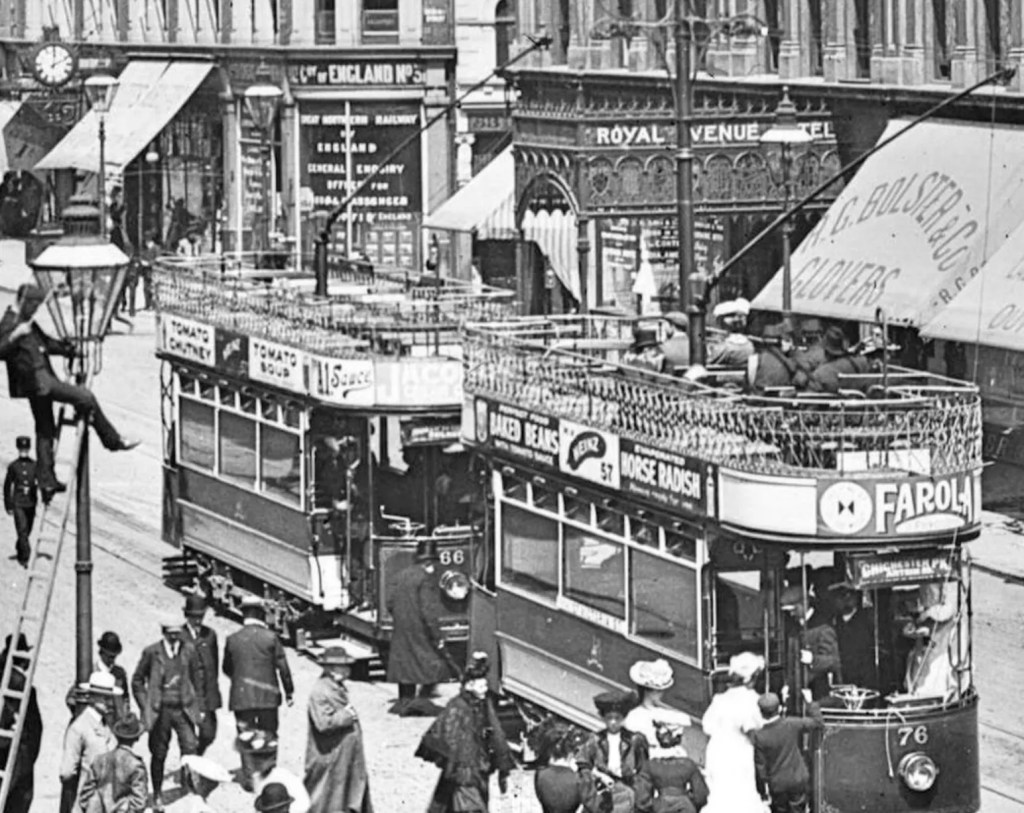

Trams in Royal Avenue

The IRA were the first to extend indiscriminate attacks from shootings to bombings. In late November 1921, bombs (hand grenades) were thrown onto two trams, one in Corporation St on 22nd November and one in Royal Avenue two days later. The trams’ destination boards made it clear that the first was carrying shipyard workers home from Workman Clark, while the other was bound for the Shankill.19

Five days after the Royal Avenue attack, loyalists responded in kind, though not degree, when a bomb was thrown into Keegan St in the Market area; it bounced off the door of a house and when mother-of-eight Annie McNamara opened the door to investigate, the bomb exploded, fatally wounding her.20

Children were soon added to the bombers’ lists of legitimate targets: on 13th February 1922, Catherine Kennedy, Ellen Johnston, Mary O’Hanlon and Rose-Anne McNeill were among a group of girls playing with a skipping rope in Weaver St when a loyalist threw a bomb among them: the four were killed and another fifteen children wounded.21

Catherine Kennedy, one of the children killed in the Weaver St bombing, Irish News

Bombs were also used to attack the homes of members of the opposing community, sometimes following well-worn paths of sectarian reprisal. On 31st March 1922, a Catholic man, Francis McFlynn of Unity St in Carrick Hill succumbed to wounds he had sustained three days earlier when a bomb was thrown over a roof from Wall St, which ran parallel. The same day that McFlynn died, a bomb was thrown into the home of the Protestant Donnelly family in nearby Brown St, killing thirteen-year-old Joseph and his three-year-old brother Francis.22

Eight people were killed over the course of summer 1921 in unselective shootings. There were a further seven deaths from such shootings after November 1921, but these were over-shadowed by the indiscriminate use of bombs in an effort to ensure as many casualties as possible were suffered by the other side: 28 people were killed this way.

Killings by the police “murder gang”

The question of responsibility for the killings will be discussed separately in a future blog post, but the deaths of fifteen Catholic civilians are usually attributed to the actions of a group of policemen, known to nationalists as the “murder gang.” These are distinctive enough to be considered in their own right.

Initially this group was led by District Inspector Richard Harrison, but after his promotion to County Inspector, District Inspector John Nixon took charge. Just as colleagues of Special Constable Sturdy avenged his killing, the “murder gang” took revenge in the immediate aftermath of the killings of police officers, both regular and Specials.

Constable Thomas Leonard, whose killing prompted the first appearance of the police “murder gang”

Their first appearance was on the night of 25th September 1920, following the killing by the IRA of Constable Thomas Leonard – John McFadden was killed in his Springfield Road home in retaliation, although he was not an IRA member. Nor was Patrick Duffin, killed in his home in Clonard Gardens on 23rd April 1921 in response to the killing of two Auxiliary Cadets by the IRA; Duffin’s younger brother Dan was in the IRA but the older brother was not, as “he had an inward fear he might fail his comrades in some great operations.”23

After this, the killings perpetrated by the “murder gang” were notable, not so much for their frequency, but for their ferocity.

The revenge taken in the early hours of 12th June 1921 for the killing of a policeman who the IRA suspected was a member of the “murder gang” verged on sadism, both psychological and physical:

“The door was opened to them by Mrs McBride and Nixon said to her he wanted her husband to come to the Barrack for a few minutes. [Alexander] McBride was taken out in his night attire. He was not allowed to dress, and shortly after the car left the house, Mrs McBride heard a number of shots. That morning McBride’s body was found riddled with bullets two miles from his home and Nixon called on Mrs McBride to express his sorrow at the death of her husband and she recognised him as the person in charge of the party who had taken him away the previous night.

The party next proceeded to … the house of Malachy Halpenny – a member of the AOH. Halpenny was dragged from bed by Gordon and Sterritt and taken to the Crossley, struggling the while. He was beaten with butt ends of rifles, and taken out to the Ligoniel Road about half a mile from his home, was riddled with bullets, his body thrown across a barbed wire fence and dragged across it into a field, thus tearing his flesh to ribbons. People living in a Villa close by heard Halpenny moaning for almost twenty minutes. When found on Sunday morning at about 6 a.m. it was found that seventeen shots were fired into his body, the soles of his feet pierced with a bayonet and his testicles also torn out by a bayonet.

The foregoing was supplied by members of the RIC who supplied signed statements.”24

A third man, William Kerr, also a Hibernian, was also killed by the “murder gang” that night.

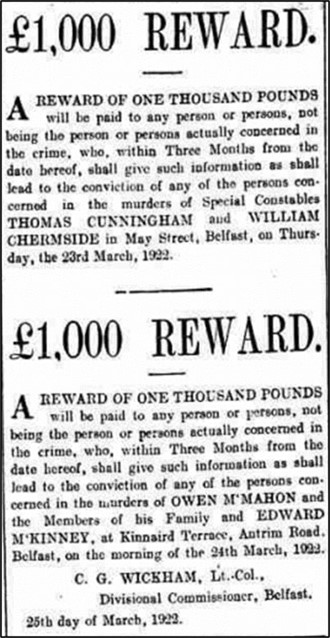

Their next attack was not until March 1922, when they retaliated for the killing of two Special Constables in the Market area. The McMahon family killings was a particularly notorious event of the Pogrom and has been written about extensively; as Tim Wilson said:

“… it violated the accepted conventions of that type of violence … by their very nature, reprisals were retrospective in their self-legitimation. Their reactive nature implied at least some relation in scale to the original offence. By attempting to kill eight men for the previous murder of ‘only’ two policemen, the McMahon intruders spectacularly breached this convention of proportionality.”25

Equal rewards offered by the RIC for help convicting the killers of the two Specials and the McMahon family

A week later, following the killing of Constable George Turner on the Old Lodge Road, the “murder gang” struck again, in what became known as the “Arnon Street killings”.

They first went to Stanhope St, the street from which they believed the shot that killed Turner was fired; they broke into the house of John McRory and shot him dead in his kitchen. They broke into several other houses but left on finding no men present. Then, around the corner in Park St, Bernard McKenna, a father of seven, was killed while lying in bed.26

Next they went to Arnon St which ran parallel to Stanhope St. The front door of the Walsh family home was broken down with a sledgehammer – they found Joseph Walsh in bed with his seven-year-old son Michael and his two-year-old daughter Brigid. Joseph Walsh was not shot, but instead was battered to death with the sledgehammer while his son died from gunshot wounds the next day.27

A Protestant man named George Murray, married to a Catholic and living in the same street, had a narrow escape:

“One of the three policemen had a revolver and the other two had guns. These men went out. Immediately after, seven armed men – five in police uniform and two in civilian clothes – entered. They had a cage car outside. On letting down the child I had in my arms one of the party (who had previously decided as to which of them was to do the shooting) fired at me. They then left.”28

The grandson of William Spallen was lucky to be spared in the killing frenzy:

“On the night of 1st April 1922, I was in bed with my grandfather. My grandmother was buried that day and we went to bed at 6 o’clock. At 11 o’clock two men came into the room, one was in the uniform of a policeman. They asked my grandfather his name and he said William Spallen. The man in plain clothes fired three shots at my grandfather. When I cried out he said ‘lie down or I will put a bullet in you.’ This man snatched the money that my grandfather had to settle up the expenses of my grandmother’s funeral; it was £20. I was 12 years old on the 11 February last. I know that if I tell a lie I will go to Hell. I could recognise the man in plain clothes I had seen him before on the Old Lodge Road.”29

Curfew-related killings

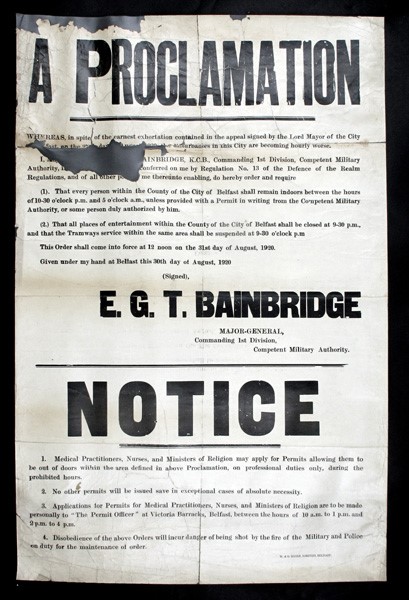

Belfast was placed under a military curfew from 31st August 1920 onwards: all people had to remain indoors between 10:30pm – 5:00am. During the Pogrom, six people were shot and killed by British military or by police for failing to halt when spotted on the streets after curfew.

The first such killing actually pre-dated the imposition of the curfew, but the circumstances were so similar to the others that it can be included under this heading. On 25th July 1920, taxi-driver David Dunbar was shot dead for not stopping his taxi at a military checkpoint in Northumberland St, between the Falls and Shankill Roads.30

Curfew order dated 28th August 1920

The most tragic of the curfew-related killings was that of Elizabeth Bray, spotted by a military patrol in Castle St in the city centre on 7th February 1921. When challenged by the patrol, she kept moving and they shot her from a distance of five yards; at the inquest into the dead woman’s death, her father explained that she was deaf – she would not have heard the soldiers’ challenge.31

Her father could have been forgiven for wondering why, if they were only five yards away from her, a lorry-load of soldiers could not simply arrest one woman walking on her own instead of shooting her?

Summary and conclusions

There were 423 civilians killed during the Pogrom, of whom 249 were Catholic and 174 Protestant; this split was in marked contrast to that of the wider population of Belfast, which was 24% Catholic and 76% Protestant; it also demonstrates the extent to which fatal violence was disproportionately directed at the minority.

For the first year or so of the Pogrom, communal rioting was the main form of violence – opposing crowds sought to do battle with each other and there were struggles for territorial control and attempts to inflict or prevent damage to homes and property. In that context, the 90 killings during rioting were the most common form of fatal violence, accounting for two-thirds of all the civilians killed in this period.

However, from the summer of 1921 onwards, other means of killing began to emerge alongside those during rioting – now, specifically homicidal intent was much more explicit. By then, both sides had acquired the weaponry to act on those intentions: loyalists were, at least in part, armed by the state through the Special Constabulary, while the IRA had developed more clandestine ways of getting guns. Six people were killed at close range and a further eighteen by snipers up to November 1921.

But after the re-mobilisation of the Specials that month, this trend accelerated and killings of individuals at either close range or long distance became dominant. As Roger McCorley put it: “The attacks on the Nationalist areas became much more serious and since the mobs had by this time practically disappeared from the field, the fight gradually took on a purely military complexion, i.e. the fight became more and more a fight between two disciplined bodies.”32

Rioting did not end after November 1921 – there were a further 28 killings in that setting after that month. But those were dwarfed by the 110 killings at close range and 79 killings by snipers in the same period.

In parallel with the heightened urge to kill, whether at close range or with rifles, there also emerged a new urge to kill as many as possible of the opposing side in a single attack. At first this took the form of indiscriminate shooting but both sides quickly learned that the best way to maximise fatalities was to resort to bombs. This almost marked a return to the crowd violence of the first phase of the Pogrom except now, instead of group against group, it involved individuals with bombs against groups. 43 people were killed in such unselective killings, all but seven of them after November 1921.

Unsurprisingly, given the general imbalance in fatalities, Catholic civilians predominated among those killed under most all of the headings examined: 74 v 42 Protestant civilians killed at close range, 61 v 38 killed by snipers, 26 v 17 killed in unselective shootings and bombings. More Protestants than Catholics died in curfew-related killings, 5 v 1. However, the most notable exception to the general rule was killings during rioting, where slightly more Protestant civilians were killed than Catholic, 62 v 56.

The killings of Catholic civilians by the police “murder gang” followed no pattern, other than one of increasing savagery. The one unifying factor was the urge to avenge fellow-policemen who had been killed and even then, there was inconsistency as not every killing of a policeman gave rise to a retaliation. Those of Constable Francis Hill on 27th December 1921, or Constables James Cullen and Patrick O’Connor both on 10th March 1922 and even, three days later, that of Sergeant Christy Clarke, believed by the IRA to be a key member of the “murder gang,” all went unavenged. In all, the “murder gang” hit back at civilians on only five occasions, but the last two of these involved two of the most notorious examples of mass fatalities of the whole Pogrom – the killings of the McMahon family and those in and around Arnon St just over a week later.

The use of bombs and sledgehammers to kill civilians and the killings of children call into question whether the combatants of the Pogrom were really “disciplined bodies” to the extent that McCorley characterised them as being. They were certainly organised, but their discipline appears to have been quite dispensable, easily set aside when the urge to act with sectarian brutality became paramount.

The next blog post will examine the killings of those combatants by each other.

References

1 Tim Wilson, The Belfast Troubles at One Hundred in Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid, Marie Coleman & Paul Bew (eds), Northern Ireland 1921–2021: Centenary Historical Perspectives (Ulster Historical Foundation, Newtownards, 2022), p32.

2 Belfast News-Letter, 11th August 1920.

3 Northern Whig, 6th April 1921; Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 21st May 1921.

4 Northern Whig, 6th July 1921.

5 Northern Whig, 7th April, 15th June 1922.

6 Belfast News-Letter, 7th January 1922.

7 Northern Whig, 6th July 1922; ibid., 17th June 1922.

8 Belfast News-Letter, 5th January 1922; Northern Whig, 2nd March 1922.

9 Belfast Telegraph, 30th August 1922.

10 Seán McNally file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives (MA), MSP34REF61252.

11 Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), MA, WS0389.

12 Charles McCaull Stewart file, MSPC, MA, MSP34REF10918.

13 Northern Whig, 29th June 1922.

14 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 8th April 1922; Belfast News-Letter, 5th May 1922.

15 Belfast News-Letter, 23rd July 1921.

16 Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 18th June 1921; Northern Whig, 29th June 1921.

17 Irish News, 11th July 1921.

18 Northern Whig, 12th & 19th August 1921.

19 Belfast News-Letter, 23rd & 25th November 1921.

20 Irish News, 30th November 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 7th January 1922.

21 Belfast News-Letter, 4th March 1922.

22 Belfast Telegraph, 3rd May 1922; Northern Whig, 27th April 1922.

23 Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22, (Beyond the Pale Publications, Belfast, 2001), p76-77.

24 Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, Ernest Blythe Papers, University College Dublin Archives (UCDA), P24/176.

25 Tim Wilson, ‘“The most terrible assassination that has stained the name of Belfast”: the McMahon murders in context’, Irish Historical Studies, Volume 37, No. 143 (May 2010). For more on the McMahon family killings, see Kieran Glennon, ‘You boys say your prayers – the McMahon family killings, March 1922’ in Tommy Graham (ed.) The Split: From Treaty to Civil War 1921-23, (Wordwell Books, Dublin, 2021).

26 Irish Independent, 3rd April 1922; Northern Whig, 4th July 1922. See also Patrick Gannon, ‘In the Catacombs of Belfast’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Volume 11, No. 42 (June 1922).

27 Ibid.

28 Extracts from statutory declarations on Arnon Street and Stanhope Street massacre, National Archive of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach S1801.

29 Ibid.

30 Belfast News-Letter, 6th August 1920.

31 Belfast News-Letter, 5th March 1921.

32 Roger McCorley statement, BMH, MA, WS0389.

Leave a comment