The IRA’s Northern Offensive, May 1922 – Part 4. The final instalment in this series of blog posts looks at how the northern and southern governments responded to the offensive.

Part 1 can be read here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2022/12/28/we-have-set-up-a-military-council-for-the-north/

Part 2 can be read here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2023/01/07/belfast-city-to-be-held-up-republican-troops-to-occupy-positions-in-sufficient-strength-to-hold-same/

Part 3 can be read here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2023/01/21/only-called-off-at-the-last-moment-because-of-some-mans-intervention/

Estimated reading time: 35 minutes

Unionist reaction

James Craig’s Unionist government reacted to the offensive in two ways.

The first was to activate the internment provisions of the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act which had been passed in April. Although lists of those to be interned had been drawn up immediately afterwards, they were not acted on until after the killing of Unionist MP William Twadell by the Belfast IRA on 22nd May.1

Unionist MP William Twadell, whose killing prompted the introduction of internment

In the first three days of internment, 348 nationalists and republicans were interned across the north – but not many of these were IRA activists, as most of them were either on the run, on active service or had fled to Donegal:

“A few IRA officers, generally of lower rank, were lifted. Far less than 10% of those arrested during and after the sweep were active members of the IRA. The vast majority of those arrested were nationalists and pro-Treaty. Factors of commonality included professional occupation or economic independence, nationalist (particularly pro-Treaty) outlooks, Catholic faith and the personal disdain by a local constable (often a neighbour or business/political competitor).”2

However, over time, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC – successor from June to the old Royal Irish Constabulary) did succeed in capturing more IRA members who eventually joined the other internees on the prison ship SS Argenta; ultimately, 728 men and women were interned between May 1922 and 1924. Apart from the loss of members actually captured, an equally important effect of internment was the panic that it created among the IRA at the mere prospect of being caught. By the end of June, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Wickham, the RUC Divisional Commissioner, was able to gloat that, “in Belfast the spectacle of the floating internment palace in Belfast Lough before their vision acts as a warning to Sinn Feiners to curb their enthusiasm for their evil activities.”3

The second government response to the offensive was to unleash the Specials. On 31st May, a pro-Executive unit of the Belfast IRA killed a Special Constable in Millfield while attempting to disarm him – a police riot ensued: “the Specials ran amok, and shot up practically every Catholic area in the city; the death toll for that day was 12 and upwards of 50 were wounded. This was the hardest blow the civil population had got, and it almost broke their morale.” May 1922 marked the worst month for deaths in the entire duration of the Belfast Pogrom, with 74 people killed, all but ten of them after the IRA’s attack on Musgrave St Barracks.4

The District Commandant of the B Specials in south Belfast was one-time UVF Larne gunrunner Fred Crawford and even he noted, “I asked DI Armstrong if the men were out of hand and he admitted they were extremely exasperated at the murders that had just taken place of their comrades.”5

B Specials’ District Commandant Fred Crawford – suspected his own men were “out of hand” ©PRONI (INF/7/A/3/63)

The ferocious onslaught on Belfast nationalists by the Specials and by loyalist mobs continued during June: the IRA’s Belfast Brigade Operations Report had an appendix, stretching to fifty-five closely-typed pages, which catalogued the attacks mounted across Belfast during that month alone.6

Aftermath

Throughout July, the 3rd Northern Division sent a weekly stream of pleading reports to GHQ in Dublin.

On 7th July, the divisional Adjutant, Séamus McGouran, bemoaned the continuing lack of assistance from outside Belfast:

“These [police raids] together with the fact that the men see no sign of receiving any support from any of the other Northern Divisions inside the Six County area, and that they can get no guarantee from their Officers that these Divisions are going to assist in the future in order to withdraw the enemy activity, is having a very serious effect upon the morale of our troops in these areas.”7

Séamus Woods, O/C 3rd Northern Division – wrote repeatedly to GHQ in Dublin

Séamus Woods, 3rd Northern’s O/C, met Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy and Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy in Dublin two days later and Mulcahy proposed holding a meeting of IRA officers from across the north. On 14th July, Woods wrote again, urging the speedy scheduling of this meeting, otherwise, “If they succeed everywhere as they are succeeding in Belfast, it will not be long till the Northern Government will have complete recognition from the population of the Six Counties.”8

What Woods did not realise was that, between the meeting on 9th July and his follow-up letter, there had been a significant change in Dublin. On 12th July,

“Mr Collins announced that the following arrangements had been made in connection with the Army and directed that they should be gazetted:

War Council of Three

A War Council of Three had been created as follows:-

Michael Collins, General Commanding in Chief

Richard Mulcahy, General Chief of Staff and Minister of Defence

Eoin O’Duffy, General in Command, S.W. Division.”9

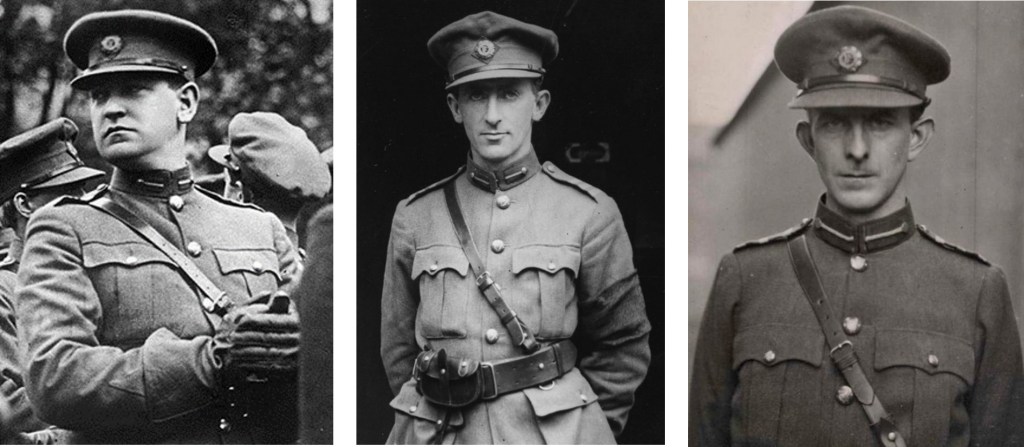

The self-appointed War Council of Three: Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Eoin O’Duffy

In order to prosecute the Civil War in the south which had begun on 28th June, Mulcahy had now superseded O’Duffy as Chief of Staff. However, Collins was floundering in relation to the north – on 24th July, he told Mulcahy, “Meanwhile I’ll ask the Government for an indication of the lines of future policy towards the Northern Government.”10

By 20th July, the IRA in Belfast had had enough – Woods told GHQ: “Under the present circumstances it would be impossible to keep our Military Organisation alive and intact, as the morale of the men is going down day by day and the spirit of the people is practically dead.”11

Another lengthy lament by Woods followed on 27th July, summarising everything that had happened between the signing of the Truce in July 1921 to the planning of the Northern Offensive and 3rd Northern’s role within that, concluding that:

“The people who supported us feel that they have been abandoned by Dail Eireann, for our position today is more unbearable than it was in June 1921. Then the fight was a national one and our suffering was in common with all Ireland. Today the people feel that all their suffering has been in vain and cannot see any hope for the future … the Divisional Staff feel they can not carry on under the circumstances, nor can we in justice ask the Volunteers and people to support us any longer when there is not a definite policy for the whole Six County area, and our position as a unit of the IRA under GHQ defined.”12

The much-anticipated meeting that Woods had been yearning for was finally scheduled for 1st August in Portobello Barracks.

Endgame

On 31st July, Mulcahy wrote to Collins, setting out points that he felt should be included on the agenda for the meeting and expressing a desire to avoid having to listen to any northern whingeing:

“(1) TRAINING

Assuming that we will accept at the Curragh under the Reserve authority up to 800 or 900 men from the Six-County area for training.

(2) ORGANISATION

The re-organisation both of Divisions and Brigades to make the Northern area co-terminus with the Six-County area.

(3) COMMAND

The setting up of a separate Command for the Six-County area.

Policy:

(a) Military: To avoid any conflict with the Specials or the British Forces in the area.

(b) Political: A Peace Policy essential.

The return to their work of men finished their period at the Curragh.

It is most important to keep the meeting to the discussion of definite constructive work and future policy, as there will be a definite tendency to bemoan their position and to look for explanations, etc., as to how they got into it.”13

The proposal under “Organisation” is important as it meant that those remnants of the northern IRA still reporting to GHQ would now be re-structured in line with partition.14

Mulcahy’s advocating of a peace policy, both military and political, is also significant as it came only a week after Collins’ musing about asking the Provisional Government to determine future policy on the north – after all, Mulcahy, in his other role as Minister for Defence, was a member of that government; this is an early indication of what way he was leaning in that regard.

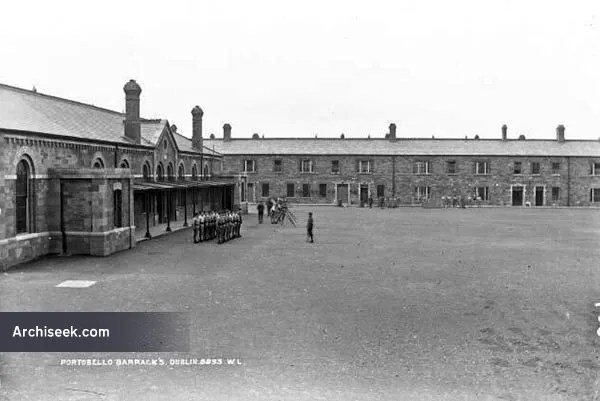

Portobello Barracks, Dublin, where Collins and Mulcahy met the leaders of the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions on 2nd August 1922

The meeting, postponed until 2nd August, was attended by Collins and Mulcahy, as well as Adjutant-General Gearóid O’Sullivan, Quartermaster-General Seán MacMahon and Director of Organisation Diarmuid O’Hegarty from GHQ; the northerners present were Woods and his Vice O/C Roger McCorley from 3rd Northern, 2nd Northern’s O/C Tom Morris and his divisional Quartermaster J. Mallin, and Patrick Casey, Vice O/C of the Newry Brigade (part of Frank Aiken’s 4th Northern but one which had not gone anti-Treaty).15

The meeting decided that a new North-Eastern Command would be formed, consisting of two Divisions and two Brigades: 2nd Northern would add Derry city to its existing area of counties Derry and Tyrone, 3rd Northern would now encompass the whole of county Down as well as Belfast and county Antrim, while counties Armagh and Fermanagh would each constitute an independent Brigade. Mulcahy felt Morris should become the temporary Chief-of-Command. Morris had 100 men in Donegal to transfer to the Free State Army and another 140 to go to the Curragh. 3rd Northern would confirm numbers to be sent to the Curragh at a future point, but the full-time Belfast Guard, which had been funded by GHQ since February, would be stood down immediately. No ordinary volunteers, but only officers, from Armagh and Fermanagh would be brought to the Curragh.16

The most significant decisions reached were:

“(1) That all IRA operations in the Six-Counties would cease forthwith.

(2) That men who were unable to remain in the Six Counties would be handed over a Barrack at the Curragh Camp, where they would be trained under their own Officers to such tactics as would be applicable to the nature of fighting in the Six Counties.

(3) That these men would not be asked to take part in any activities outside the Six Counties.

Documents from Officers – which are still in the Department – indicate that there was the intention of re-opening hostilities in the Six-County area at the first suitable opportunity.”17

In connection with the last point, Collins told the northerners, “… with this civil war on my hands, I cannot give you men the help I wish to give and mean to give. I now propose to call off hostilities in the North and use the political arm against Craig so long as it is of use. If that fails the Treaty can go to hell and we can all start again.”18

Ernest Blythe, member of the Provisional Government’s North East Policy Committee

This was exactly what his audience wanted to hear but what Collins neglected to tell them was that, just a day earlier, the Provisional Government had established a sub-committee to review its northern policy. On 9th August, Ernest Blythe wrote to his fellow committee members echoing the peace policy first proposed by Mulcahy ten days previously:

“Guerrilla operations within the Six Counties can have none of the success which attended our operations against the British … The continuance of guerrilla warfare on any considerable scale can only mean within a couple of years the total extirpation of the Catholic population of the North East. The events of the past few months on the part of our supporters make that evident. As soon as possible all military operations on the part of our supporters in or against the North should be brought to end …

The line to be taken now and the one logical and defensible one is a full acceptance of the treaty. This undoubtedly means recognition of the Northern Government and implies that we shall influence all those within the Six Counties who look to us for guidance, to acknowledge its authority and refrain from any attempt to prevent it working …

As it is quite evident that the Catholics of the Six Counties cannot by use of arms protect themselves we should, on receiving satisfactory assurances from the British, urge them to disarm.

The ‘Outrage’ propaganda should be dropped in the Twenty-Six Counties. It can have no effect but to make certain of our people see red which will never do us any good.

The belligerent policy has been shown to be useless for protecting the Catholics or stopping the pogroms. There is of course the risk that the peaceful policy will not succeed. But it has a chance where the other has no chance.”19

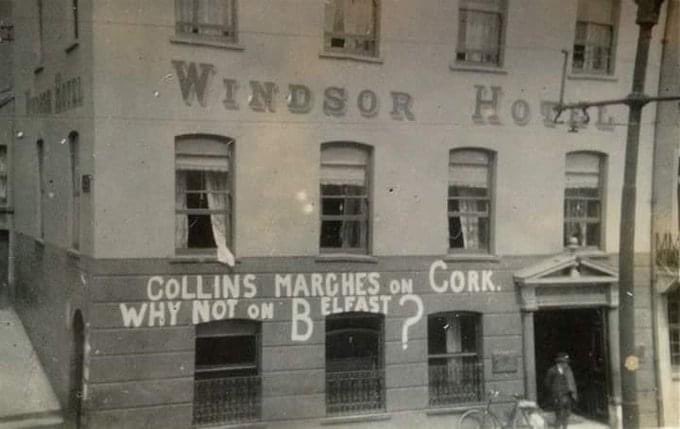

On 19th August, the rest of the government agreed with the committee’s recommendations and decided that “It was considered desirable that a peace policy should be adopted in regard to future dealings with the North and Ulster.” Collins was not at this meeting but the decision was conveyed to him two days later while he was in Cork. The following day, he was killed.20

Although Collins was informed of the new peace policy, those in the Curragh were not. By the end of August, a total of 379 men from 2nd and 3rd Northern had gathered there, ostensibly to train for a new campaign, although these numbers were so paltry as to barely constitute a battalion of armed northerners – certainly not enough to contemplate a fresh invasion of the north.21

Members of the Antrim Brigade, 3rd Northern Division in the Curragh, 1922

By mid-October, with no new plan yet unveiled by GHQ, the penny was beginning to drop. After another series of imploring memos from Woods, Mulcahy bluntly replied,

“I am not in a position to, nor do I see the necessity for saying more with regard to the question raised in your memo of 18th October, than that the policy of our Government here with respect to the North is the policy of the Treaty.

I don’t presume to place any detailed interpretation on what are called ‘assurances that the GHQ would stand to the North’ and ‘Money would be no obstacle.’”22

The Northern Offensive was now definitively over.

Summary and conclusions

Sinn Féin had first failed to address the reality of partition after its implementation in mid-1921 and had then failed to remove it in the Treaty negotiations later that year. Collins subsequently attempted to co-operate with the Unionist government in the first abortive Craig-Collins Pact of 1922, while at the same time hoping for ultimate unity via the Boundary Commission.

Meanwhile, a local crisis around the condemned prisoners in Derry Gaol and the arrest of the “Monaghan footballers” in January soon escalated during the spring into kidnappings, clashes with the Specials all along the border and sectarian reprisals by them inside it. The Provisional Government had given its imprimatur to this with the decision to “hamper” the northern government, O’Duffy and the Ulster Council simply brought the military consequences of that decision to fruition.

The ground then shifted dramatically with the split in the IRA and the formation of the anti-Treaty Executive at the end of March. This happened against a backdrop of escalating violence in Belfast – February 1922 had been the worst month to date for killings since the start of the Pogrom in July 1920, with 50, but it was immediately eclipsed by March, with 71. The first IRA Army Convention came only two days after the McMahon family killings, while the country was still reeling in shock from that event.

By the time the Four Courts were occupied, Collins’ second diplomatic initiative had already failed miserably – the fond hopes of the second Craig-Collins Pact that “Peace is today declared” were blown away along with the gunsmoke of the Arnon Street killings. O’Duffy’s military strategy had also proved largely fruitless – although the “Monaghan footballers” and kidnapped unionists had all been released, the attacks along the border had done little but prompt reprisals both there and in Belfast and the northern government had not been “hampered” to any meaningful degree.

Meanwhile, the Executive appeared to be taking the lead in relation to the north, with Joe McKelvey and Peadar O’Donnell elected as members, the Belfast Boycott re-instated and the symbolic occupation of Dublin buildings with Orange or imperial associations in order to house Belfast refugees. Collins was now in danger of, at best, appearing unable to influence northern events, or at worst, being completely left behind by those willing to explore non-diplomatic avenues.

When writing to his Provisional Government colleagues on 9th August, Blythe noted, “Heretofore our Northern policy has been really, though not ostensibly, dictated by Irregulars. In scrapping their North Eastern policy we shall be taking the wise course of attacking them all along the line.” His use of “dictated” was an over-statement, but his analysis was fundamentally correct – the policy was created with the anti-Treaty Executive in mind.23

Creating the plan for the Northern Offensive in tandem with them returned an element of control over the northern agenda to Collins: diplomacy had failed twice and even the churchmen present at the 11th April meeting of the North East Advisory Committee had not demurred at the prospect of a more robust approach.

More importantly, a second benefit of the plan was that working together offered the prospect of at least applying a brake to the deepening split with the Executive. This was Collins’ over-arching priority after the Army Conventions. He, O’Duffy and Mulcahy therefore embarked on the new strategy for what it could prevent in the south, rather than what it could achieve in the north.

The offensive also allowed GHQ to keep 2nd and 3rd Northern close to them. Although Charlie Daly and McKelvey had been replaced by the more-amenable Morris and Woods, O’Duffy knew that the wider loyalty of these Divisions remained brittle, with elements of both already lost to the Executive. Involving them in an offensive that was armed and jointly-sponsored by GHQ would avert the risk of further elements going the same way, thus exacerbating Collins’ political exposure on the northern front. That the offensive stood no realistic chance of achieving military success was secondary – if not immaterial: it was enough that 2nd and 3rd Northern be kept busy.

But practical realities soon impinged on the ability of Collins and O’Duffy to deliver their side of the plan. The arms swaps with the Southern Divisions were devised to avoid the potential embarrassment of weapons supplied by the British to the Provisional Government for the purpose of building up the Free State Army turning up in the north. The prospect of troops from that army being captured in the north would have had far more serious consequences.

This obviously explains the countermanding order issued to Joe Sweeney’s 1st Northern. While no specific evidence has yet been found of similar orders being issued to 5th Northern and 1st Midland, it is reasonable to assume that they were and for the same reason. The nearest proof we have is a mid-1920s Free State review which stated, “… a decision appears to have been taken that there would be no fighting on the Border or around it – which decision meant that there were no ‘offensive’ operations carried out by the 1st Northern or 1st Midland or 5th Northern Divisions.”24

Speaking decades afterwards, Morris felt that the prospect of those divisions invading the north had never been realistic:

“GHQ did send arms to the North but he thinks [that] as some say there was to be military help for the North from the South in May 1922 is all fairy tales. They were too busy getting ready in the South to fight each other to be bothered about the North.”25

However, even if O’Duffy, acting as Chief of Staff but putting Collins’ interests paramount, had valid reasons for calling off the three Divisions which had been attested into the Free State Army, this does not explain why, after 2nd Northern’s attacks soon proved ineffectual, 3rd Northern was then allowed to enter the fray without a warning that they were now acting alone. The Antrim Brigade certainly went into action believing that help would soon be coming:

“Our Division and Brigade officers felt that a useful blow could be struck at the Craigavon power before it was definitely established and arranged a wide spread attack on Unionist points, civil and military. In this decision we were encouraged and definite assistance promised by the 1st, 4th and 5th Northern Divisions, which was agreed to by General Collins. After details had been arranged we struck on 19th May expecting all Divisions, North and South of the Border to take part, but in this we were sadly disappointed. We had started something which we could not hope to carry out successfully alone and had taken up a position from which we could not withdraw.”26

This appears to make the countermanding order issued to 4th Northern especially problematic. Aiken was still perched on a neutral fence in relation to the GHQ-Executive split and would remain there until early July; nor had his men been attested into the Free State Army, so that concern might not seem to be applicable.

Why then was 4th Northern told to stand down and equally, why was 3rd Northern not informed of the various countermanding orders? It is clear from McCorley’s visit to O’Duffy at the end of May and worse, from McGouran’s report to GHQ at the start of July, that the truth was being kept from them.27

A likely explanation of the countermanding order issued to Aiken is that while not formally attested, 4th Northern was still reporting to GHQ and, being very visibly ensconced in Dundalk Barracks south of the border, an attack by it against the north could be perceived as ultimately emanating from the Provisional Government. Collins and O’Duffy could no more allow that than they could allow the involvement of their attested Divisions. However, actions by 2nd and 3rd Northern, both based entirely inside the north, could more plausibly be explained away as simply a continuation of existing sectarian violence, particularly in the case of the latter.

With the original grandiose plan for the Northern Offensive thus whittled down from all six Divisions of the Ulster Council to just two plus Lehane’s force in Donegal, the results were predictably pitiful. The remaining participants were unable to be more than a violent irritant to the northern authorities and by late May, the offensive had dwindled to the arson campaign to which the Belfast Brigade turned in a futile attempt to maintain a last vestige of momentum.

Also by late May, Collins had an alternative strategy to forestall a split in the south and no longer had to rely on the Northern Offensive to play that role.

His negotiations with Éamon de Valera to create an electoral pact for the impending General Election came to fruition when the agreement was signed on 20th May, although the details were not announced in the Dáil until two days later. Then on 24th May, the committee appointed by the Provisional Government to draft the new Free State Constitution completed its work; the intentionally republican draft omitted the oath to the British monarch and other aspects of the Treaty that were particularly repugnant to its opponents, including those on the Executive.28

But within days, the draft Constitution had been angrily rejected by the British government, who “affirmed that the Provisional Government had to choose between appeasement of de Valera and support for the Treaty.” Winston Churchill threatened that an attempt to adopt a republic by such constitutional subterfuge would prompt resumption of military operations in the south.29

The overwhelming British response in the Battle of Belleek-Pettigo provided a salutary lesson in this regard – the British Army remained the most powerful military actor on the island and Downing Street would not hesitate to deploy it, not just to support Craig’s regime, but to enforce the Treaty. Apart from the immediate local task of capturing the border villages, the British Army’s actions also sent a clear message to Collins of what “immediate and terrible war” would entail if he attempted to deviate from the letter of the Treaty.

Later during June, the Unionist government, by utilising the Specials’ predilection for sectarian violence, quickly completed the process of crushing dissent north of the border, the northern IRA being powerless to stop them. Belleek-Pettigo also served as a deterrent against any attempt to balance the odds by military intervention from any quarter in the south. So by the time the Civil War began, partition had thus already been secured and Collins backed into a corner with no option but to implement the Treaty settlement in full.

As July progressed, the majority of the northern IRA simply dropped out of action while most of the remainder who hadn’t yet been interned fled west or south of the border.30

Authorship of the Provisional Government’s northern peace policy is usually attributed to Blythe, on account of his 9th August memo. But Mulcahy actually began promoting this policy ten days earlier and Collins immediately approved it, telling the Portobello meeting that he was calling off hostilities in the north. Blythe’s memo thus merely represented the civilians in the government belatedly recommending a policy that, unknown to them, the military leaders had already adopted.

It then remained to Collins and Mulcahy to mop up the stragglers of the northern IRA in a way that kept them out of trouble. Training in the Curragh for a mythical new offensive both mollified the remnants of 2nd and 3rd Northern and reduced the likelihood of them defecting to the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. Their officers’ reliance on the southern military leadership was so ingrained and their faith in it so blind that they failed to see through Collins’ rhetorical trumpeting that “the Treaty can go to hell and we can all start again.”

But by then, the northern IRA had already proved their willingness to believe fairy tales.

References

1. For example, Joe McPeake, Adjutant of the IRA’s 2nd Battalion in the city “Was recommended for internment on 18-4-22” – see McPeak, Joseph, Little May St, Belfast, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/2344.

2. Denise Kleinrichert, Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta, 1922 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2001), p62.

3. Ibid., p337-368; Divisional Commissioner’s bi-monthly report, 30th June 1922, PRONI, HA/5/152.

4. O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 20th July 1922, Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/B/77.

5. Diary of Fred Crawford, quoted in Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22 (Belfast, Beyond The Pale Publications, 2001), p242.

6. Appendix, Adjutant 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 7th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77. In terms of content and commentary, this report is strikingly similar to Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom, a pamphlet written in 1922 by a Belfast priest, Fr John Hassan, under the pseudonym G.B. Kenna; it may reflect additional research conducted by Hassan but not included in his final manuscript, but instead shared with the IRA.

7. Adjutant 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 7th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

8. O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 14th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

9. Provisional Government decision, 12th July 1922, in File on Army Appointments, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach S1318.

10. Commander-in-Chief to Minister for Defence, 24th July 1922, quoted in File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Ernest Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

11. O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 20th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

12. O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 27th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

13. Chief of Staff to Commander-in-Chief, “Meeting of Six-County Officers on Tuesday, 1st August”, 31st July 1922, Mulcahy papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

14. The majority of Frank Aiken’s hitherto neutral 4th Northern had gone anti-Treaty following the capture of Dundalk Barracks by Dan Hogan’s 5th Northern on 16th July.

15. Memorandum, “Six-County”, 3rd August 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77. J. Mallin is not named as divisional Quartermaster in any of the nominal rolls relating to 2nd Northern.

16. Ibid.

17. File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

18. Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins (London, Arrow Books, 1991), p383. Coogan quotes from an affidavit by Thomas Kelly, divisional Engineer of 2nd Northern, but does not provide a source for this quotation. Kelly is not listed as an attendee in the minutes of the meeting (see reference 14 above); a simple explanation would be that whoever took the notes recorded “J. Mallin Quartermaster” in error for “T. Kelly Engineer.”

19. Ernest Blythe to North East Policy Committee, 9th August 1922, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/70.

20. Minutes of Provisional Government meeting, 19th August 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach S1801A.

21. File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

22. Commander-in-Chief to O/C 3rd Northern Division, 20th October 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/287.

23. Ernest Blythe to North East Policy Committee, 9th August 1922, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/70.

24. File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

25. Fr Louis O’Kane notes on Tom Morris interview, 8th September 1967, Fr Louis O’Kane Collection, Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library & Archive, CÓFLA LOK IV.A.08.

26. Activity Report, 2 Brigade 3 Northern Division, Military Service Pensions Collection, Military Archives, MSPC/A/49.

27. Although I cannot recall the date of our conversation, the late Dr Éamon Phoenix told me that, while researching his Northern Nationalism, he had interviewed Séamus Woods’ sister; she told him that Woods never forgave Aiken for failing to take part in the Northern Offensive.

28. David Fitzpatrick, Harry Boland’s Irish Revolution (Cork, Cork University Press, 2004), p296; Coogan, Michael Collins, p322.

29. Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green : The Irish Civil War (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 2004), p107.

30. As an example, for figures relating to the Belfast Brigade of 3rd Northern, see https://www.theirishstory.com/2022/04/14/belfast-republicans-and-the-treaty-split-of-1922-part-2/#.Y6tE3HbP2Um

Leave a comment