The IRA’s Northern Offensive, May 1922 – Part 2. The second in this series of blog posts looks at what the planning and preparations for the Northern Offensive entailed.

Part 1 is available here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2022/12/28/we-have-set-up-a-military-council-for-the-north/

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes.

Planning the Northern Offensive

In August 1922, Rory O’Connor wrote from captivity in Mountjoy Prison to Poblacht na hEireann War News, an anti-Treaty bulletin; he recalled the formulation of the plan for the Northern Offensive:

“…at one meeting of the Coalition Army Council, at which Mulcahy, O’Duffy, Mellows, Lynch and myself were present … we actually discussed co-ordinated Military Action against the N.E. Ulster, and agreed to an Officer who would command both republican and Free State troops in that area. It should be remembered that at this time the ‘Government’ was publicly declaring that it was the ‘Mutineer’ section of the army which was fighting the Ulster people. At that meeting I have referred to, someone suggested the evacuation of the Four Courts, and Mulcahy laughingly said as long as we held that place, the war in N.E. Ulster would be attributed to us. We, of course, had no objection.”1

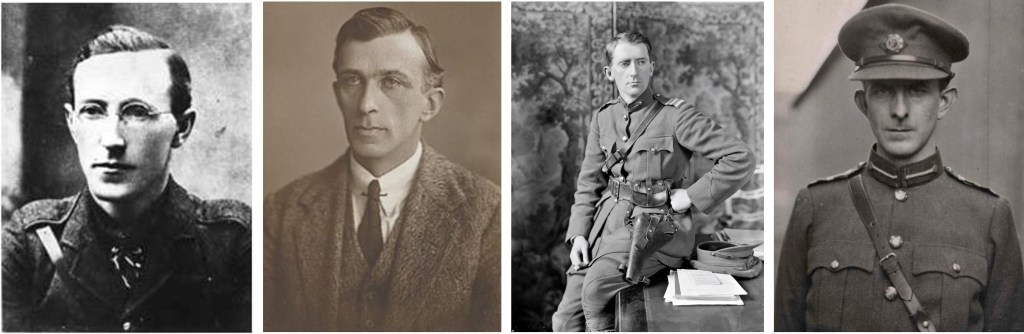

The plan for the Northern Offensive was created by, among others, (L-R) Liam Lynch, Rory O’Connor, Richard Mulcahy and Eoin O’Duffy

The joint plan that was put in place worked admirably, at least for the time being, in terms of averting a final seismic split between pro- and anti-Treaty factions in the south that could result in civil war. The Northern Offensive would now be the glue that held them together, war in the north serving to ward off war in the south.

But in military terms, the strategic plan could, at best, be charitably described as optimistic. A more realistic assessment would be that it was delusional. What it entailed for the various Northern Divisions was as follows:

“On May 2nd a general attack to be launched on all posts.

1st North. Div. to take all posts in general sweep from Donegal concentrating on Derry.

2nd to occupy all posts in area attempting no mass movements by troops but more or less preparing ground for occupancy by 1,5,4 divisions.

5th to attempt to occupy all posts within area paying special attention to Enniskillen to join up with 4th N.D. above Armagh

3rd Antrim movements of troops to be moderately large scale, attempts to be made to capture one or two key positions in Antrim

Belfast City to be held up – Republican troops to occupy positions in sufficient strength to hold same

North Down This unit to devote attention to harassing and annoying concentrations of English forces – Newtownards and Ballykinlar. Down and other towns to be occupied. Junction to be effected with 4th N. forces advancing towards Belfast.

4th Assault on Armagh Military Barracks, advance on Portadown. Banbridge to be occupied and advance continued towards Belfast. Junctions of troops from South Down above Banbridge. Right flank to be guarded from Ballykinlar.

All R.I.C. posts and personnel to be wiped out.

All effectives in every Division were to be mobilised and used in the push.”2

An even more fanciful version of the plan was later recalled by Liam McMullan, the Antrim Brigade Engineer:

“It was said at the time that Seán Mac Eoin was going to lead thirty thousand men into the Six Counties and we, in the Six Counties, were ordered to perform such a cause of destruction in the Six Counties that would draw off the Six County forces from the frontiers to the interior and so facilitate Mac Eoin’s entry to the Six Counties.”3

But the Unionist government had been continually expanding the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or Specials) since it gained control over policing in the north in November 1921. In March, it proposed to the UK Government (who were funding the USC) that the numbers of A and B Specials be increased to 5,800 and 22,000 respectively.4

An RIC Lancia armoured car

A further proposal tabled in May by its Military Advisor, Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood, would see 3,000 regular Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) augmented by 8,290 A Specials, the B Specials would grow to 25,000, “ordinary” C Specials would number 10,000 while there would be up to 17,000 C1 Specials, primarily recruited from loyalist paramilitary groups. On top of all this, there were 17 battalions of British military stationed in the north, with a paper strength of roughly 17,000.5

British troops in York St, Belfast – there were seventeen battalions of military in the north

Faced with those numbers – and ignoring McMullan’s wishful thinking – the northern IRA were about to embark on a campaign they could not possibly win. The idea that 3rd Northern could capture and hold Belfast – or even just the majority-nationalist areas of it – was preposterous. The city’s population was split roughly three-quarters Protestant to a quarter Catholic and even within the nationalist community, republicans represented a minority compared to supporters of the Nationalist Party. But according to the plan, the Belfast Brigade was supposed to take the city, then hold out like Davy Crockett in the Alamo until Aiken’s 4th Northern relieving columns came marching up the Lagan valley.

Southern reinforcements

Apart from the general rising of all northern IRA units, the plan had two other elements.

First, the anti-Treaty IRA Executive agreed to send a contingent of their most seasoned War of Independence veterans from Munster to Donegal. They were to be led by a west Cork officer, Seán Lehane:

“It was decided that an IRA officer be appointed from the South, and a staff of officers to assist him, that they were to proceed to the present counties of Donegal, Tyrone, Derry, part of Fermanagh and Cavan, and under the direction of the IRA Army Council, to assist the present General Frank Aiken Minister for Defence, in war against the Crown forces along the Border and further inland in the Six Counties.

I was selected from the Southern Command and sent to take charge of 1st and 2nd Northern Divisions. Charlie Daly RIP was made Deputy or Vice Divisional O/C. We had with us Mr M. Donegan, Brigade O/C, Mr Jack or Seán Fitzgerald, Kilbrittain, Brigade O/C, Mr Seamus Cotter, Minane Bridge, Brigade O/C. I was instructed by General Lynch to take my orders directly from General Aiken. The Truce was not to be observed up there, to get inside the Border wherever, whenever. To force the British general to show his real intention, that was to occupy Ballyshannon, Sligo and along down.”6

(Back row) Seán Lehane O/C, Charlie Daly Vice O/C, Jack Fitzgerald Brigade O/C, some of the leadership of the Munster anti-Treaty IRA sent to Donegal

An important clue regarding the speed with which the plan was devised and put in motion is offered by a brief newspaper report of 21st April: “The advance guard of a Southern Division has arrived at Finner Camp. They belong to the new Executive section of the Army.” So, within a week of the occupation of the Four Courts, Lehane and his men were already in place in Donegal.7

Arming the northern IRA

The final element of the plan was that the Northern Divisions were to be armed by the Provisional Government. Therefore, on 21st April, the O/Cs on the IRA’s Ulster Council met in Clones to be told the outline of the plan and to state their requirements in terms of the quantities of arms and ammunition that they would need to carry it out. Pádraig Quinn, Quartermaster of 4th Northern, was present:

Pádraig Quinn, Quartermaster, 4th Northern Division

“Meanwhile I was listening to the requisitions to be made to General Headquarters. They were made out at the meeting in Clones.

Rifles

.303

Revolvers

.45(5)1st Div.

550

55,000

250

7,5002nd Div.

500

50,000

250

7,5003rd Div.

300

30,000

500

15,0004th Div.

500

50,000

300

9,0005th Div.

Supplies drawn as attested troops

Grenades According to supplies available

Cheddar Ad lib

The Midland Division (Mac Eoin) drew supplies as attested troops mostly. Though along with Frank I submitted these requisitions to O’Duffy and MacMahon (apparently Mulcahy had already been informed by Frank) I was only to be responsible for the arming of the Second, Third and Fourth Northern Divisions. The First and Fifth would draw and move their own supplies (and Seán Mac Eoin’s Midland Division would do likewise). The first priority was the Third, Seamus Woods. I met his Quartermaster Tom McNally.”8

However, Collins was anxious that his government’s involvement be kept hidden – above all, weapons provided by the British for the arming of the new Free State Army must not be found in the hands of the IRA in the north. As Lehane noted:

“Both parties – Republican and Free State – were to co-operate in giving us arms and supplies, but General Collins insisted on one thing, mainly; that activities were to be in the name of the IRA and that we were to get arms – rifles – from Cork No. 1 Brigade and that he would return rifles to Cork 1 from rifles handed over by the British.”9

Two implications jump out from the list of arms and ammunition that each Division sought.

The first is that, as noted in the table in the case of 5th Northern, and in Quinn’s comments in relation to 1st Northern and 1st Midland, these Divisions would draw their supplies as attested troops – the Northern Offensive was thus to involve not just the IRA in the north but also officially sworn-in elements of the new Free State Army in the south.

Documents in Military Archives verify the fact that some of the intended participants were Free State Army units: in the case of 1st Northern, the author’s grandfather, divisional Adjutant Tom Glennon, “transferred to the Regular Army” in February 1922 while the divisional Quartermaster Frank Martin “transferred from IRA Feb. 4th 1922”. In fact, a search of the Military Service Pensions Collection website for applications made under the 1924 Military Service Pensions Act (for which service in the National, or Free State Army, was a prerequisite) shows that 33 of 54 Donegal IRA applicants had joined the Free State Army before the end of May 1922; similarly, 24 of 47 Monaghan IRA applicants had joined by that date (the remaining applicants from both counties joined later).10

The second implication of the arms requisitions is that, if we compare the numbers of personnel in each Division in December 1921 to the quantities of weapons sought at Clones, the non-attested Northern Divisions were not exactly demanding:

2nd Northern 1,414 men: 500 rifles, 250 revolvers

3rd Northern 1,506 men: 300 rifles, 500 revolvers

4th Northern 1,216 men: 500 rifles, 300 revolvers11

Even after the weapons were delivered, between roughly a third and half of each Division would still have to rely on whatever stocks of armaments they already held; the IRA had been notably short of guns throughout the War of Independence and the Northern Divisions were no different in this regard. Thus, they would be embarking on the campaign woefully under-equipped.

An IRA arms dump captured in Milan St in the Lower Falls

Despite this, after the meeting in Clones, Woods’ outlook was considerably more positive than it had been at the meeting in Dublin ten days earlier, especially when he met his own divisional officers the next day:

“All present were very anxious that the whole Six County area should strike … In No. 1 [Belfast] Brigade I found every officer prepared and anxious to go ahead. In No. 2 [Antrim] Brigade I found a similar state of affairs. In No. 3 [East Down] Brigade the O/C, although he had previously signified his intention of remaining loyal to GHQ, turned Executive when he heard of operations going to commence.”12

However, Aiken still had misgivings – Quinn noted:

“Michael Collins wanted him to be General Officer Commanding a new Command of the five Northern Divisions with the Midland Brigade (Mac Eoin) but that he did not want it. He would act as Chairman of a Northern Committee of divisions … I understood from F. that Michael Collins was the instigator of this general offensive which was timed for May the second, 1922. I was thinking over what he had already told me especially the running of a campaign by a committee and that not a small one, he went on to say that ‘If I became General Officer Commanding these divisions, responsible for the whole Northern campaign, they would be able to blame me for failure – alternatively if they failed in their commitments in their supplies to us.’”13

Events would prove Aiken to be at least partially prophetic.

Arms and the men

In preparing for the offensive, there were two main channels for getting weapons into the north – up the east coast and via Donegal. The main depot for the former route was Dundalk Barracks, which had been taken over by 4th Northern after the departure of the British. Patrick Casey was Vice-O/C of the Newry Brigade of that Division and he recalled that the barracks became a treasure trove of armaments: “I remember well the tremendous activity in and about Dundalk. Thousands of rifles, sub-machine guns, grenades, boxes of ammunition, land mines, detonators, etc. were passed over the border by various routes and dispersed throughout the six counties.”14

3rd Northern Quartermaster, Tom McNally, brought the weapons north:

“I brought some up the coast and landed them at Guns Island near Séamus Woods’ place in Co. Down in a little 12-ton motor-boat, about 200 rifles and 30/40,000 rounds of ammunition. We swapped 2 Lewis guns for Thomsons [sic]. I brought 5 Thomson guns by rail. We were to receive 200 rifles for each of our brigades – 600 in all. The 200 for Belfast went to Antrim.”15

However, Belfast Brigade O/C Roger McCorley said that GHQ had left them short:

“We were not completely satisfied with the quantities of rifles, etc. allotted to the Belfast area since the 150 rifles which we did eventually receive only increased our firepower by 50%. The supplies of ammunition which we received from GHQ were inadequate as only seventy rounds per rifle were sent to us although we had been promised about 200 rounds per rifle.”16

A further indication that the Belfast Brigade did not suddenly enjoy a cornucopia of weapons can be seen from documents subsequently captured by the RUC. In January and February 1922, the IRA’s 2nd Battalion in the city had an “effective strength” of 281 men; but at the start of May, according to weapons returns provided by each of its component companies, the Battalion had the sum total of thirty-six rifles and thirty-one revolvers. When additional amounts were distributed during May – these, presumably, had come from Cork as their serial numbers were recorded – they got twenty-five more rifles and another twenty-six revolvers. A positive view would be that their armaments had almost doubled – but in reality, their armoury had simply expanded from almost nothing to half-nothing.17

Apart from the issue of quantity, Quinn was shocked at the poor quality of some of the arms sent north:

“As the stuff came in from the Park – the Magazine Fort – I was appalled at the state – the poor quality of the guns – they were military type Lee Enfield rifles bound with wire to prevent them from bursting – worn out on the Western Front and used by the R.I.C. for rifle grenades. Their accuracy was nil as a rifle grenade always destroys rifling. Some I picked up showed very early dates – none later than 1917. I did not see any of the R.I.C. short carbine type passing through. These were kept in good condition and being shorter would have been better for us. Apparently good rifles were given in the early stages in the arming of the Dublin Guards (the old A.S.U. and Collins personal troops). The ammunition (.303) came in hardwood (oak & mahogany) boxes of 1000 with a sealed metal inner case but was nearly all dated 1915-16, not the best type but good enough for cordite deteriorates with age.”18

There were other disruptions to the supply routes – Quinn said that “Dan Hogan objected to Morris transversing [sic] his Division in much the same manner as a medieval baron would have objected but Frank got the matter sorted out.”19

Dan Hogan, O/C 5th Northern Division and putative medieval baron

Nor did the transfer of rifles from the Divisions in the south go smoothly. Tom Scanlan, an officer in the 3rd Western Division, said:

“In connection with the arrangements of arms to the north, none actually were sent, but I recall the fact that we received a hundred rifles from the south, which were to be transferred to the northern commands, Collins having promised to send a hundred rifles to the southern Division to replace them, but he failed to keep his promise, we had to return the rifles to the south.”20

However, some weapons were indeed sent north via Donegal – Joe Sweeney said:

“Collins sent an emissary to say that he was sending arms to Donegal, and that they were to be handed over to certain persons – he didn’t say who they were – who would come with credentials to my Headquarters. Once we got them we had fellows working for two days with hammers and chisels doing away with the serials on the rifles … About 400 rifles in all were taken to the northern Volunteers by Dan McKenna and Johnny Haughey.”21

So, not for the last time, there were officers in the Free State Army, running guns across the border for use by the northern IRA, with the knowledge of and under instructions from their superiors in Dublin, and with the involvement of a man named Haughey.

But Sweeney also stopped some weapons going into the north. Patrick Hurl, Quartermaster of 2nd Northern, had travelled up from Dublin with two lorry loads of rifles:

“We brought these rifles to Drumboe Castle and from there we took them in small quantities to the border and smuggled them into the six counties. When we had more than half over safely General Sweeney seized the remainder as there was a rumour that the remainder were to be handed over to the Republicans in Donegal.”22

To complete the picture of slipshod arms transfers, at the end of April, a bizarre public row broke out between the Free State and Executive Chiefs of Staff, O’Duffy and Lynch respectively. In An tÓglach, the IRA’s magazine which was then freely sold on news-stands, O’Duffy accused his counterpart of delays in sending arms north; the next day, Lynch replied via the Irish Times, saying he had in fact acted quickly following a request received:

“The following supplies of arms and ammunition were forwarded within 36 hours: 30 Thompson guns, 8,000 rounds of ammunition for T.M. guns, 10,000 rounds .303, 75 rifles. I also sent ten machine gunners. Any of these supplied, I afterwards learned, did not get to the north, and the gunners after being detained for a week at Beggar’s Bush [Free State GHQ], were ordered home to their own areas after all being so urgently required by phone for the north. It is very easy to judge where the responsibility lies for the situation which now exists.”23

The secrecy of the arms transfers was now compromised and the northern authorities were alerted.

References:

1. Rory O’Connor to Poblacht na hEireann War News No. 50, 31st August 1922, https://digital.ucd.ie/view-media/ucdlib:265004/canvas/ucdlib:265427.

2. Pádraig Quinn Collection, Kilmainham Gaol Museum (KGM), 20MS-1P41-08. Although there is no town called Down in that county, that is what Quinn subsequently wrote in his notes; it is likely he meant Downpatrick.

3. Liam McMullan interview, 19th April 1965, Fr Louis O’Kane Collection, Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library & Archive, LOK.IV.B31.

4. Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary, 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), p95.

5. Ibid., p120-122.

6. Seán Lehane to Military Service Pensions Board, 7th March 1935, Florence O’Donoghue Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 31,423 (9). This document is not included in Lehane’s Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) file: Seán Lehane, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34REF22228.

7. Donegal Vindicator, 21st April 1922.

8. Pádraig Quinn Collection, KGM, 20MS-1P41-08. “Cheddar” or “war cheddar” was the IRA’s nickname for a type of explosive.

9. Lehane to Military Service Pensions Board, 7th March 1935, O’Donoghue Papers, NLI, Ms 31,423 (9).

10. Major Thomas Glennon personnel file, Military Archives, SDR1083; Frank Martin, MSPC, Military Archives, 24SP01885; http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/brief.aspx. Tom Glennon and Frank Martin would subsequently become brothers-in-law when the latter married Kathleen Glennon in November 1922.

11. Divisional strengths, December 1921, Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/A/32. The same documents also lists 3,712 men in 1st Northern and 1,820 in 5th Northern. Numbers for all five Divisions may vary from those in the nominal rolls compiled in the 1930s as part of the Military Service Pensions process; however, at the time that the Northern Offensive was being planned, these were the forces that GHQ believed they had at their disposal.

12. O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 27th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

13. Pádraig Quinn Collection, KGM, 20MS-1P41-08.

14. Patrick J. Casey statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives, WS1148.

15. Thomas McNally interview, Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/99.

16. Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389.

17. Internment of Henry Crofton, Joy St, Belfast, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, HA/5/961A.

18. Pádraig Quinn Collection, KGM, 20MS-1P41-08.

19. Ibid.

20. Tom Scanlon to Florence O’Donoghue, 1st August 1952, O’Donoghue Papers, NLI, Ms 31,421 (12).

21. Joe Sweeney, interviewed in Kenneth Griffith & Timothy O’Grady, Curious Journey – An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (London, Hutchinson, 1982), p275.

22. Patrick Hurl to Frank Aiken, 19th November 1927, Frank Aiken Papers, UCDAD, P104/1261.

23. The Irish Times, 27th April 1922.

Leave a comment