The IRA’s Northern Offensive, May 1922 – Part 1. During a Hedge School podcast last summer, History Ireland editor Tommy Graham lamented that he had been trying repeatedly to “get to the bottom” of the IRA’s Northern Offensive of May 1922, but with only limited success. This is my explanation of what happened. As the subject remains complicated, controversial and contested, this blog post will appear in four instalments.

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes.

Early 1922: hostages and counter-hostages

The Truce of July 1921 did not bring peace to the north. Nor did the signing of the Treaty in December bring peace to the border, which had already been created by the Government of Ireland Act of December 1920 – in contrast, it ushered in a period during which IRA units along the border made concerted efforts to destabilise it.

The first series of incidents stemmed from a failed escape attempt from Derry Gaol at the start of December 1921: two warders were overdosed with chloroform and died. On 12th January, three IRA members, one of them a warder at the jail, were sentenced to death for their participation in the bungled effort. The sentences were due to be carried out on 9th February.

Derry Gaol

Two days after the death sentences were handed down, ten members of the Monaghan Gaelic football team, including the O/C of the 5th Northern Division, Dan Hogan, were arrested while travelling to Derry, supposedly to play a match; documents found on them revealed that the football match was a mere cover for an attempt to break the condemned men out of Derry Gaol.

Hogan was very much the protégé of his one-time predecessor, Eoin O’Duffy, who had just been appointed as Chief of Staff of the IRA; prior to that, O’Duffy had been the Chief Truce Liaison Officer for Ulster and so enjoyed the trust and confidence of the IRA’s Northern Divisions. On 7th January, while still in that role, he had written to Tom Fitzpatrick, O/C of the Antrim Brigade, “refusing to acknowledge the existence of the Northern Government, stating that a state of war existed and directing him to regard the Truce as non-existent.”1

Eoin O’Duffy, Chief of Staff of the IRA from 10th January 1922

It is worth pointing out that O’Duffy wrote this on the very day that he, along with a majority of the Dáil, voted to approve the Treaty, and before the Derry prisoners had even been sentenced. It was not the case that he had simply adopted a newly-belligerent policy. The previous September, speaking on a platform in Armagh alongside Michael Collins, he had said: “They were told it was not right to use force against the people of the North … but if they decided they were against Ireland and against their fellow countrymen, they would have to take suitable action … if necessary they would have to use the lead against them.”2

If Hogan and the others were to be held captive by the Unionist government, O’Duffy was determined to respond in kind – at the end of January, he wrote to Michael Collins:

“You understand that I have arranged for the kidnapping of one hundred prominent Orangemen in Counties Fermanagh and Tyrone. This was to take place last Tuesday, the 24th inst. But on account of the agreement arrived at between Sir James Craig and yourself, I postponed action until tomorrow, 31st inst. And failing to hear from you to the contrary the kidnapping will commence at 7 o’clock tomorrow evening.”3

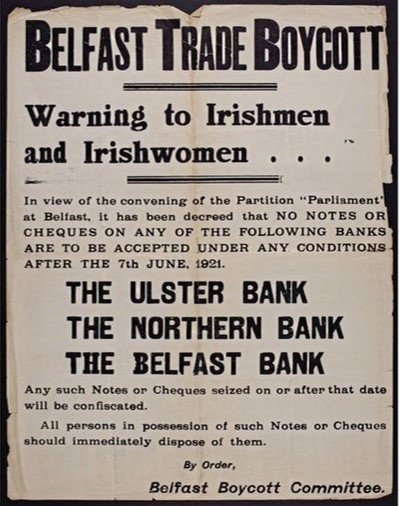

The agreement to which O’Duffy referred was the first Craig-Collins Pact, signed on 21st January, the terms of which involved the calling off of the Belfast Boycott instituted by the Dáil in the summer of 1920 in response to the outbreak of the pogrom in the city; this gesture by Collins was to be reciprocated by Craig “facilitating” the return of expelled Catholic workers when trade improved. The tripartite Boundary Commission provided for in the Treaty was also to be replaced by a bilateral arrangement between Craig and Collins, with no British involvement.

Not for the last time, O’Duffy sublimated his military plans to the exigencies of Collins’ political strategy, as the kidnap operation did not go ahead on the 31st. However, the Pact collapsed at a follow-up meeting between the two leaders on 2nd February – the breaking point was the amount of territory that would be reviewed for transfer by the Boundary Commission; Collins was determined that it would be substantial, Craig that it would be minimal.

A meeting of the Provisional Government that night resolved that “the Belfast Parliament is to be hampered in every possible way.”4

It is important to note that “hampering” the Unionist government went beyond military action. Sinn Féin-controlled local authorities in the north were encouraged to continue to provide their allegiance to the Dáil rather than the Northern Ireland Government; similarly, teachers in the north who refused to recognise Craig’s regime would have their salaries paid from Dublin. No date had yet been set for the first meeting of the Boundary Commission, so it may be the case that such measures, as well as the continuing military pressure, were intended to demonstrate “the wishes of the inhabitants” in the areas that would be under review.5

It should also be pointed out the decision to “hamper” the Unionist government was Provisional Government policy – it was not Collins engaged in some kind of solo run; Collins’ policy and that of his government were identical.

The new directive was all that O’Duffy needed to hear and a few days later, on the night of 7th/8th February, his postponed plan was put into effect. Chief Secretary for Ireland Hamar Greenwood reported to the UK Cabinet on 13th February that a total of forty-three unionist civilians and members of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”) had been kidnapped from Tyrone, Fermanagh and Armagh and taken south of the border – this included two lorries of Specials ambushed at Newtownbutler, possibly while responding to other kidnappings. On the other hand, twelve IRA members from Leitrim and Longford, all members of the 1st Midlands Division, were captured entering Enniskillen in Fermanagh, in the course of the same operation; a later Free State Government report stated that “The 1st Northern [primarily based in Donegal], however, took part in the raids on the 7th/8th February 1922 but no men of that area were captured [by the northern authorities],” although two Donegal unionists were also kidnapped.6

Ironically, Winston Churchill had already applied pressure on the British Viceroy to reprieve the condemned men and an announcement to that effect was made the day after the kidnappings.

Destabilising the north – the Ulster Council

The kidnapping raids were undertaken by a new IRA Ulster Council which had just been set up on his own initiative by O’Duffy. In early March he wrote to Collins, clearly seeking neither permission nor forgiveness:

“I do not know if you are aware we have set up a Military Council for the North consisting of the following: Divisional Commandant McKeown, Divisional Commandant Sweeney, Divisional Commandant Morris (this is Major Morris who I appointed in room of Divisional Commandant Daly whom I found it necessary to discipline), Divisional Commandant McKelvey, Divisional Commandant Aiken, Divisional Commandant Hogan. Frank Aiken is Chairman of the Council and Davis, Midlands Assistant Divisional Quartermaster, is Quartermaster for the area. He has a central dump in Cavan and all supplies for the North will go through him from the Quartermaster General.”7

This body had broader objectives than simply kidnappings – it was “directed towards preventing the Northern Government from functioning effectively to consolidate the area which had been allocated to it under the Government of Ireland Act of 1920.”8

Frank Aiken, O/C 4th Northern Division

Aiken had misgivings about being a mere co-ordinator rather than having direct overall command: “They wanted me to take charge of our Div[ision]s. in the N[orth]. I refused to take responsibility but Mulcahy was keen … I wanted it as an official status. That was after Collins/PM [Prime Minister Craig] Pact.” There was even some confusion later over whether Aiken had actually taken on this figurehead role, as Florence O’Donoghue said, “Commandant Aiken was willing to agree provided that he was given freedom of action, but this was not forthcoming and the proposal did not materialise.”9

Regardless of who was directing operations, units constituting the Ulster Council continued to act after the kidnappings. On two nights running on 9th and 10th February, USC patrols in the border village of Clady in Tyrone were ambushed by the IRA – on the second night, a Special Constable was killed.10

A noteworthy aspect of the Clady incidents is that this particular part of Tyrone fell within the operational area of Joe Sweeney’s 1st Northern Division, specifically the 1st Battalion of its 4th Brigade. The O/C of that battalion, Michael Doherty, said that “Claudy [sic] at this time was subjected to incessant raids by members of the Special Constabulary; arrested two members of the Specials as reprisals. In an engagement with Specials they were driven out of the village and one member was killed and several others wounded.” So, at this point, men under Sweeney’s command were actively engaged in combat with the Specials.11

The next notable incident was not planned by either side but occurred due to a disastrous error in planning on the part of the USC.

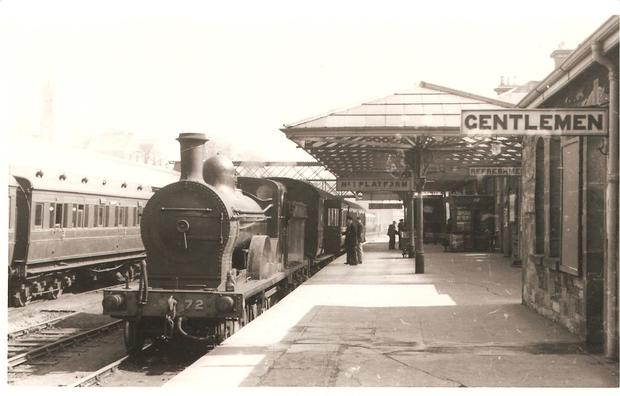

On 11th February, a party of nineteen Specials, some armed, set out by train from their depot in Newtownards via Belfast, bound for Enniskillen; however, the route chosen required them to stop in southern territory to change trains at Clones in Monaghan. The local IRA were alerted to their presence, made their way to the station and a gun battle ensued. Four Specials as well as the IRA Commandant were killed, nine Specials and several civilians were wounded and only seven of the Specials managed to avoid captivity and escape back across the border.12

Clones railway station, scene of a firefight between the IRA and Specials

Craig was incensed and wanted to send 5,000 Specials into the south to rescue the kidnapped unionists and captured Specials but Churchill refused to allow this. Instead, he insisted that Craig release the “Monaghan footballers” and in response, Collins arranged for the release of the unionist hostages, with most being freed by 16th February.13

The release of the respective sets of prisoners failed to defuse the situation and instead, military activity continued to escalate. The northern government began trenching roads to prevent cross-border movement and sent large numbers of Specials to patrol the border. An incident on the night of 18th February is indicative of the general confusion and heightened tension at this time: a lorry of A Specials, recently arrived as reinforcements from Belfast, was fired at by a patrol of local B Specials at Spawell in Fermanagh – a Special Constable who had been travelling on the lorry was killed.14

Special Constables guarding a trenched border road

On the night of 18th/19th March, two RIC barracks were captured by the 2nd Northern Division. At Pomeroy in Tyrone (with help from a sympathetic policeman who let them in) they tied up the six RIC men and eight Specials in the barracks and removed all the weapons. A similar operation was carried out in Maghera in Derry – here, as well as the three policemen in the barracks, several others who were patrolling the town were also captured, though later released. Specials from Magherafelt tried to give chase to the Maghera raiders but the IRA blew up a bridge at Moyola and shot and killed a Special Constable.15

The next day, at Trillick, also in Tyrone, a Special Constable was killed during an IRA attack on the home of his employer, who was the local commander of the B Specials. The homes of four other Specials were burned. Three days later, also in Trillick, another Special Constable was killed by the IRA at his home. Loyalist reprisals followed immediately: Specials killed three Trillick nationalists on 24th March.16

The cycle of reprisal and counter-reprisal was intensified on 26th March, when the newly-appointed O/C of 2nd Northern, Tom Morris, issued an order to all his units “that the property of ‘prominent loyalists’ should be destroyed and that reprisals should be carried out six fold to prevent them from continuing in the same vein.” Two nights later, a flax mill in Tobermore in Derry owned by the local USC Head Constable was burned.17

The 4th Northern Division also became involved in the border clashes. On 29th March, a mixed patrol of police and Specials was ambushed at Cullaville in Armagh, resulting in the deaths of an RIC Segreant and a Special Constable. Two days later, a patrol of Specials in Newry, Co. Down was ambushed and another Special Constable was killed, reportedly by a dum-dum bullet.18

The same night, a USC patrol ambushed an IRA unit which was destroying a bridge at Dunamore in Tyrone – an IRA Volunteer who had been involved in the recent capture of Pomeroy Barracks was killed. Another patrol of Specials recently transferred from Belfast was attacked on 6th April near Garrison in Fermanagh – one Special Constable was killed and four others wounded.19

An RIC mobile patrol in Tyrone

On 18th April a nationalist was shot dead by a patrol of Specials near Caledon in Tyrone when returning from a cockfight in Monaghan; sectarian targeting by the Specials is clearly shown by the fact that two of the other (unharmed) passengers in the car were Protestant men.20

While the IRA had clearly gone on an offensive, with the USC retaliating, this sequence of events along the border in the first months of 1922 should not be confused with the Northern Offensive – the latter was aimed at completely overthrowing, rather than simply destabilising, the Unionist government, but it had its genesis in other destabilising developments within the IRA. However, the Ulster Council established in the spring of 1922 would provide the key platform from which the new offensive would be launched.

Another failed diplomatic initiative

Collins, meanwhile, had also been pursuing diplomatic approaches in relation to the north. Following the McMahon family killings in Belfast on 24th March, he and Craig had been summoned to London by Churchill; there, they agreed a second Craig-Collins Pact, signed on 30th March. Beginning with the hopeful declaration, “Peace is today declared,” the agreement specified important changes in policing in Northern Ireland:

- Special police in mixed districts to be composed half of Catholics and half of Protestants, special agreements to be made where Catholics or Protestants are living in other districts. All Specials not required for this force to be withdrawn to their homes and their arms handed in.

- An Advisory Committee, composed of Catholics to be set up to assist in the selection of Catholic recruits for the Special Police.

- All police on duty, except the usual secret service, to be in uniform and officially numbered.

- All arms and ammunition issued to police to be deposited in barracks in charge of a military or other competent officer when the policeman is not on duty, and an official record to be kept of all arms issued, and of all ammunition issued and used.

- Any search for arms to be carried out by police forces composed half of Catholics and half of Protestants, the military rendering any necessary assistance.21

James Craig and Michael Collins were brought together by Winston Churchill to negotiate the second Craig-Collins Pact

In return for these policing changes, which were intended to make the IRA redundant in terms of having to protect nationalist areas, the Pact also specified that all IRA activities in the north were to cease. The agreement concluded with both the northern and southern governments “appealing to all concerned to refrain from inflammatory speeches and to exercise restraint in the interests of peace.”22

But within days, the hope that peace would prevail proved forlorn. On the night of 1st April, an RIC Constable was shot and killed on the Old Lodge Road in north Belfast; while responsibility for the killing was later disputed, the dead policeman’s colleagues wasted no time in retaliating – within hours, RIC officers and Specials from Brown Square Barracks, led by District Inspector John Nixon, raided nationalist streets nearby. In what became known as the “Arnon Street Massacre”, four nationalists including a seven-year-old boy were shot dead in their homes and a fifth was bludgeoned to death with a sledgehammer. Craig refused to put in place an official enquiry into either the McMahon family or the Arnon Street killings. Collins’ diplomatic strategy now lay in ruins.

On 11th April, in an attempt to find a new direction, he convened the first meeting of a new Provisional Government North East Ulster Advisory Committee. From the southern side, this was attended by Collins, O’Duffy and Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy, as well as Arthur Griffith, W. T. Cosgrave and Kevin O’Higgins. Among the northern attendees were Séamus Woods, McKelvey’s replacement as O/C 3rd Northern, along with Frank Crumney, his divisional Intelligence Officer, and Seán O’Neill, O/C 1st Battalion in Belfast; Morris as O/C 2nd Northern was also there. Three northern Sinn Féin delegates, three Catholic bishops and ten priests completed the committee.23

Russell McNabb, one of the Sinn Féin members, argued that a scorched earth policy be applied in Belfast; Collins was enthusiastic about the proposal, feeling that unionists would respond positively to avert further economic damage: “I know for a good many months we did as much as we could to get property destroyed. I know that if a great deal more property were destroyed – I know they think a great deal more of property than they do of human life.”24

Mulcahy, while worried that the Provisional Government would have to foot the bill for any compensation claims arising as a result, did not see any options other than military action: “The alternative to this pact is anything like war, and war under present circumstances, burning and destruction of property is the only way we can hit Belfast men … I don’t think you will get away from the fact that if property is destroyed in Belfast now, if there is any settlement we will probably have to pay for it.”25

However, Woods, his senior commander on the ground in Belfast, was bleakly pessimistic about the military prospects:

“The Falls is the only area in which there could be a fight. The people are striving for existence in other areas. Now in the Falls there are Specials going about. We had nothing to fight against them. A cage comes along. Men attack it and the bullets glance off. Some men are killed. You have men dying day by day and men arrested for nothing. When we were fighting in the war as a whole the men had the hope that even if they were sentenced to fifteen years, they had the chance of getting out soon. The men arrested now are sentenced to 15 years and there is very little hope of their getting out inside of 15 years … The position is such that it is impossible. Sooner or later we will have to clear out of Belfast.”26

Roger McCorley runs an auction – the IRA Army Convention

On 26th March, the IRA had formally split when delegates, the majority of them anti-Treaty, attending an Army Convention which had been banned by the Provisional Government, repudiated the authority of the Dáil and instead elected an interim Army Executive to oversee the organisation.

This interim Executive included Joe McKelvey, O/C of 3rd Northern, Peadar O’Donnell from Donegal, a Brigade O/C in 1st Northern, and Michael Gallagher from Tyrone, a Brigade O/C in 2nd Northern.27

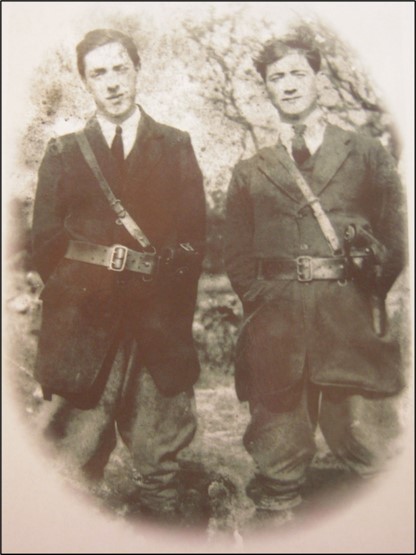

Roger McCorley, O/C Belfast Brigade, and Tom Fitzpatrick, O/C Antrim Brigade, en route to the IRA Army Convention in March 1922

Among the delegates was Roger McCorley, O/C of the Belfast Brigade – he initially leaned towards supporting the Executive:

“… certain promises of aid were made by way of making more arms and ammunition available in the north. This seemed to clinch the matter insofar as I was concerned since we were finding it very difficult to get supplies of ammunition to continue the defence of nationalist areas in Belfast … When the Convention ended I went back to my hotel and had a discussion with some of my fellow delegates. I told them I felt most unhappy about the whole position but that unless GHQ [pro-Treaty General Headquarters] would make at least as good an offer of supplies as had been made by the Executive which had been set up by the Convention, I would have no option but to advise the Belfast Brigade that they should support the Executive.”28

But at a meeting the following day, O’Duffy trumped the Executive’s offer:

“General Duffy [sic] then brought up the subject of our attendance at the Convention and I informed him that since we had been offered arms and ammunition by the Executive that I intended to support them and would advise Belfast accordingly. He told me that GHQ would be better placed to provide the arms and ammunition which we required than the Executive would be. He said that they had the markets of the world open to them … He then made me a definite promise that the GHQ would provide all the necessary supplies within a very short space of time. I told him that if that were so I would be in a position to advise the Belfast Brigade to support GHQ with whom my personal sympathies lay … on the following day the majority of delegates agreed to give their support to GHQ.”29

Although McCorley had changed his mind, O’Duffy now understood very clearly that the allegiance of the 3rd Northern to GHQ was tenuous and not to be taken for granted.

At a subsequent Army Convention held on 9th April, a new Executive of sixteen members was elected, of whom McKelvey gained the fourth-highest number of votes. O’Donnell was also elected to the new Executive although Gallagher was not. However, the election of all three at the initial Convention illustrates the extent to which the split affected divisions which have since generally been considered to have remained loyal to the pro-Treaty GHQ.30

Joe McKelvey, O/C 3rd Northern Division, was elected to the IRA Army Executive, which re-instated the Belfast Boycott

The new Executive moved quickly in relation to the north: the Belfast Boycott was re-instated, while a number of symbolic buildings in Dublin were seized to provide accommodation for nationalist refugees fleeing the ongoing violence in Belfast: the local headquarters of the Orange Order at Fowler Hall on Rutland (now Parnell) Square, the Freemasons’ Hall in Molesworth Street and the Kildare Street Club. It now appeared that the anti-Treaty Executive were the only ones providing any tangible assistance to Belfast nationalists.

Fowler Hall and the Freemason’s Hall in Dublin were occupied by the anti-Treaty IRA to house northern refugees

Two days after the North East Ulster Advisory Committee met, the anti-Treaty Executive made another surprise move which further shifted the initiative away from Collins. On the night of 13th/14th April, led by Rory O’Connor, they occupied the Four Courts in central Dublin.

References

1. Documents on IRA activities seized at St Mary’s Hall, Belfast, by RUC, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/32/1/130.

2. Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy: A Self-Made Hero (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005), p80.

3. Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins (London, Arrow Books, 1991), p344.

4. Éamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland, 1890-1940 (Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994), p181.

5. Ibid., p 178-179.

6. Pearse Lawlor, The Outrages (Cork, Mercier Press, 2011), p204-205; File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Blythe Papers, University College Dublin Archives Department (UCDAD), P24/554; Edward Burke, Donegal Loyalists and the Civil War: Fear, Adaptation and Resistance, paper delivered at University College Cork Irish Civil War National Conference, 16th June 2022.

7. Chief of Staff to Michael Collins, 10th March 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach S1801. Morris took over as O/C 2nd Northern Division after O’Duffy sacked its previous commander, Charlie Daly, on 17th February – O’Duffy claimed this was due to Daly’s poor performance, while Daly said it was on account of his opposition to the Treaty.

8. File on Pension Claims by Northern IRA Personnel, Blythe Papers, UCDAD, P24/554.

9. Frank Aiken interview, Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/90; Florence O’Donoghue, No Other Law (Dublin, Anvil Books, 1986), p254.

10. Lawlor, The Outrages, p202-203; Fergal McCluskey, Tyrone: The Irish Revolution 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2014), p119.

11. Michael Doherty, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives, MSP34REF35115.

12. Lawlor, The Outrages, p212-229.

13. Phoenix, Northern Nationalism, p181.

14. Lawlor, The Outrages, p246-247.

15. McCluskey, Tyrone, p120; Adrian Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2018), p132-133; Belfast Telegraph, 20th March 1922.

16. McCluskey, Tyrone, p120.

17. Grant, Derry, p133.

18. Lawlor, The Outrages, p256.

19. McCluskey, Tyrone, p121; Lawlor, The Outrages, p257.

20. McCluskey, Tyrone, p119.

21. Heads of Agreement between the Provisional Government and Government of Northern Ireland, 30th March 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach S1801A.

22. Ibid.

23. Minutes of meeting of North East Ulster Advisory Committee, 11th April 1922, NAI, D/Taoiseach S1011.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Freeman’s Journal, 29th March 1922; Peadar O’Donnell, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34REF60300; Michael Gallagher, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34REF23662.

28. Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History, Military Archives, WS0389.

29. Ibid.

30. O’Donoghue, No Other Law, p224.

Leave a comment