Emmet O’Connor: “Rotten Prod: The Unlikely Career of Dongaree Baird” (UCD Press)

With this biography of James Baird, Emmet O’Connor has made a vitally important contribution to our understanding of the Protestant socialists and trade unionists who were among the first victims of the Belfast Pogrom, being vilified by their loyalist co-religionists as so-called “rotten Prods.”

Estimated reading time: 25 minutes.

The labour movement in Belfast in the early Twentieth Century

The history of the Belfast working class in the first decades of the last century has been woefully under-represented in terms of books.

Henry Patterson’s Class Conflict and Sectarianism: The Protestant Working Class and the Belfast Labour Movement 1868-1920 (1980) may well be excellent but it’s £130, or roughly €150, for a second-hand copy on Abe Books. John Gray’s City in Revolt (1985) dealt with the Belfast dockers’ strike of 1907, while Austen Morgan’s Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (1991) looked at the various political currents that competed for working class loyalties in the city up to the formation of the northern state; it also had THE best book dedication I’ve ever read – “To the ‘rotten Prods’ of Belfast, victims of unionist violence and nationalist myopia.” Beyond those, Labour and the Politics of Disloyalty in Belfast, 1921-39 by Christopher J.V. Loughlin (2018) touches on the pre-partition period to an extent, but its main focus is on the inter-war years.

Emmet O’Connor’s new biography of James Baird is the first in-depth study of one of the key figures in the Belfast working class immediately after the Great War. As we discover, Baird was perhaps unique in that his union activism led to him being both driven from his employment by the shock-troops of unionism in the north, and subsequently interned by the nascent regime in the south, all within two-and-a-half years.

O’Connor begins by providing important context in terms of the alphabet soup of trade unions operating in Belfast in the early 1900s; the union of which Baird was a member gloried in the title United Society of Boiler Makers and Iron and Steel Shipbuilders – thankfully, O’Connor refers to them as the Boilermakers throughout. This was not a militant union – 95% of their income was spent on members’ benefits, such as payment for illness, accidents and unemployment, rather than on disputes.

The Boilermakers were part of the UK-wide Federation of Engineering and Shipbuilding Trades (FEST) and here O’Connor paints an important picture in terms of the divisions within the Belfast working class: with 60,000 members in the city, FEST represented a separate pole of attraction to the Belfast trades council, which encompassed only 15,000 workers, mainly members of small, weak unions in textiles and construction. The trades council was affiliated to the Irish Trades Union Congress (ITUC), while the FEST unions were more British-oriented and suspicious of ITUC’s nationalism.

The Harland & Wolff shipyard had 26,000 employees by 1919

The political outlook of members of FEST-aligned unions was also divided, as O’Connor explains: “The key problem for Belfast Labour was not the religious divide but the contradiction between the Tory [pro-imperial] politics of the bulk of Protestant workers and the Liberalism or Labourism of its British role models.” This contradiction would set labour on a collision course with unionism.1

The British Labour Party viewed Home Rule as a simple question of democracy and so were in favour of it. This naturally coloured unionism’s view of the wider labour movement, so in June 1918, Edward Carson set up the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA) to keep trade unionism in-house, an organisation which “came to accept the British unions industrially, while rejecting their politics.”2

The following year, the secretary of the Ulster Unionist Council, Richard Dawson Bates, wrote to Carson, warning him that “many of the unions are controlled by officials who hold Home Rule views.” Bates had a keen nose for detecting ne’er-do-wells bent on infiltration – a couple of years later, he said in relation to the Royal Irish Constabulary in Belfast, “Over 50 per cent of the force in the city are Roman Catholics, mainly from the South, and many of them are known to be related to Sinn Fein.”3

In relation to the labour movement, Bates’ misgivings were partly accurate: in 1919, the Belfast Labour Representation Committee applied to join the British Labour Party but were politely referred to the Irish equivalent. Although Belfast Labour decided to go solo, O’Connor notes that they “had come to a consensus on Home Rule as a better alternative to partition.”4

Baird’s early days in the trade union movement

James Baird was born into a Presbyterian farming family in Tyrone in 1871. By 1898, he had moved to Belfast and joined the Boilermakers, but it is only from a biography of one of his daughters that we learn that he defined himself as “a pronounced Home Ruler and socialist since 1893.”5

This introduces one of several plot holes in this book – no reason is given for why the son of a Presbyterian farmer made this unusual, though not unheard-of, political leap. Baird left no diaries or personal archive that might throw light on what led him to this outlook.

A second plot hole emerges when we learn that Baird was a member of the Belfast trades council from 1903. Given the FEST orientation of the Boilermakers – and O’Connor highlights the fact that the trades council had tried unsuccessfully to persuade the Boilermakers to play a more active role – it seems unusual that a member of a non- or inactively participating union would become a leading light on the council. Both of these question marks remain dangling, but without damaging the overall flow irreparably.

By 1911, Baird had become secretary of the Ballymacarrett No. 1 branch of the Boilermakers, one of its eight branches around Belfast. However, at this stage, he was still a relatively low-level union functionary.

In July of the following year, following an attack by members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians on a Protestant Sunday School outing in Castledawson, County Derry, furious loyalists drove 3,000 workers from their jobs in Belfast’s shipyards and engineering works. Similar expulsions had happened previously, but O’Connor points out that this time, 600 of those expelled were Protestant Labour supporters, Liberals and members of the Independent Orange Order – a political dimension was thus overlaid on the “usual” sectarian motivation. This was a foretaste of things to come.

A red tide: the 1919 engineering strike and the 1920 local election

A 54-hour working week had been the norm in engineering firms during the Great War, but on 21st August 1918, a rank-and-file committee chaired by Baird held a meeting in the Ulster Hall to demand a 44-hour week. The meeting agreed to defer the demand until the end of the war and left the negotiations in the hands of FEST.

The following December, FEST and the employers’ representatives agreed a move to a 47-hour week. This proposal was put to a ballot in Belfast but defeated by a landslide: fewer than 1,200 workers voted to accept it, while roughly 13,500 rejected it. When a motion calling for an unofficial strike was put, the result was even more overwhelming: 20,600 in favour and fewer than 600 against.

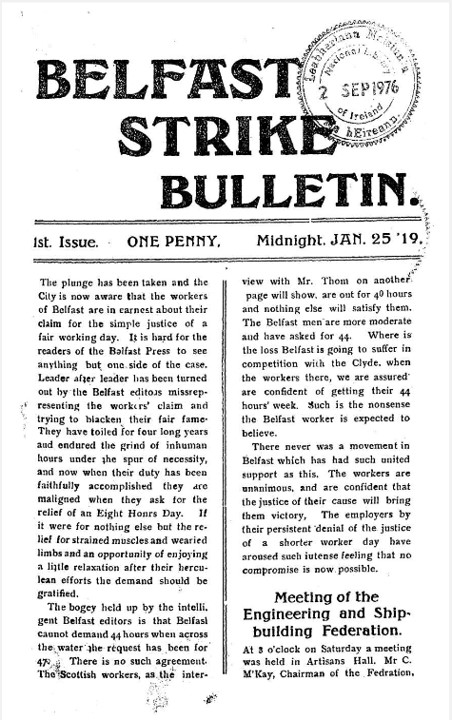

Bulletin issued by the General Strike Committee (Irish Newspaper Archive)

On 25th January 1919, the strike duly began in Belfast. A General Strike Committee (GSC) was established which ran a permit system for the supply of gas, water and electricity, all of which had been interrupted by the strike. O’Connor says that “Baird’s role on the GSC is unclear,” speculating that the committee may have preferred anonymity as way to conceal members’ anti-unionist politics.6

However, he references Morgan, who quotes from letters Baird wrote to the Northern Whig, in which he stated that workers faced a choice between “slavery … or some sort of collectivism.” Morgan states that Baird was the most prominent socialist on the GSC but that “his advocacy of socialism was the cause, or consequence, of his ousting.”7

In terms of conducting the strike, the GSC craft unions ignored the trades council, seeking no sympathetic strike action from them, and did not even reply to a telegram of encouragement sent by the ITUC. Belfast’s isolation was compounded when a parallel strike in Glasgow was ground into submission by military intervention; on 14th February, troops were similarly deployed to take over the Belfast gasworks and electricity station and the strike collapsed shortly afterwards.

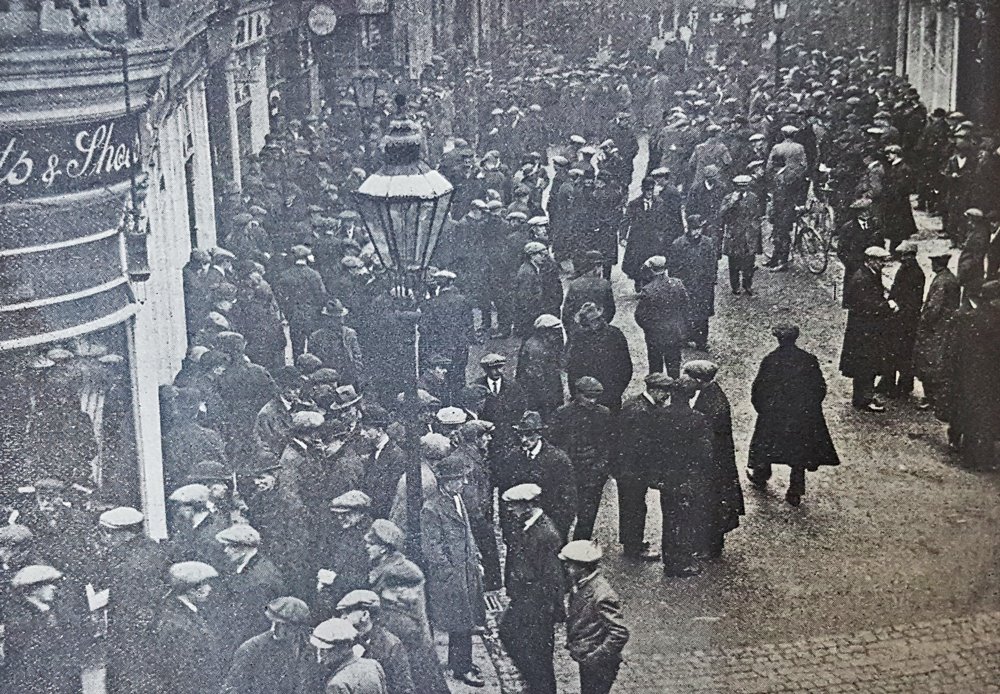

Strikers outside the GSC office in Garfield St, February 1919

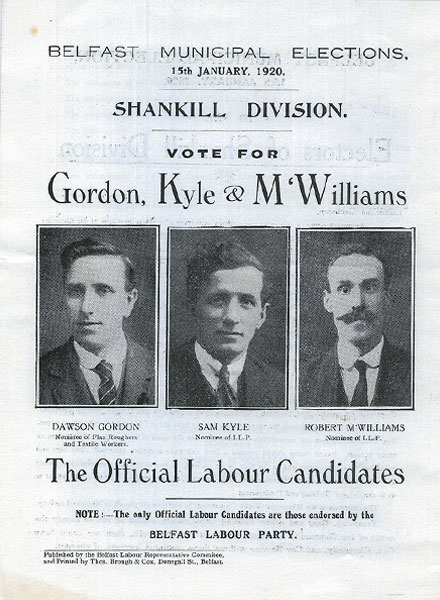

In January 1920, Baird stood as a Labour candidate in the elections for Belfast Corporation. Labour had resounding success at the polls, winning 17.7% of the vote and gaining seats for ten Belfast Labour and two Independent Labour candidates; Baird was one of the former, being elected for the Ormeau Ward in south Belfast.

His appearance at his first Corporation meeting provides O’Connor with a delightful sub-heading, “The most famous trousers in Labour history.”8 Baird had gone straight from the shipyard to the meeting in his working attire, thus giving the unionist press a nickname with which to ridicule him, “Dongaree Baird,” one which also forms the sub-title of the book. Although his attendance at Corporation meetings appears to have been sporadic, he was particularly vocal on the subject of housing.

Election poster for Labour candidates in the Shankill Ward

July 1920: workplace expulsions and the start of the Belfast Pogrom

O’Connor paints a careful picture of the genesis of the violent workplace expulsions which began in the shipyards on 21st July 1920. In terms of who planned them and carried them out, he points to a number of groups:

(a) The UULA, which by then had developed links with the right-wing, anti-Bolshevik National Democratic Labour Party in Britain.

(b) The Ulster Ex-Servicemens’ Association (UESA) set up after the war, which claimed to have 3,000 members including a sizeable contingent of shipyard workers, but about which O’Connor notes witheringly, “Carson declined to patronise it, deeming it too crass.”9

(c) The Belfast Protestant Association, originally founded in the 1890s as an anti-Home Rule organisation, which O’Connor suggests was either re-vamped or used as a flag of convenience by the UULA.

Carson arrives at “The Field” in Finaghy, 12th July 1920 © Getty Images

Carson’s speech at Finaghy on the Twelfth is widely cited as being a starting-pistol that led to the expulsions, but O’Connor makes the interesting point that Carson had been lobbied beforehand by both the UULA and UESA. Carson said:

“…these men who come forward as the friends of Labour care no more about Labour than does the man in the moon. Their real object, and the real insidious nature of their propaganda is that they mislead and bring about disunity amongst our own people and in the end before we know where we are, we may find ourselves in the same bondage and slavery as is the rest of Ireland in the South and West.”10

Loyalists subsequently gave three reasons for the expulsions: the government’s failure to crush the IRA, Sinn Féin infiltration of Labour and to recover jobs taken by Catholics during the war. However, as O’Connor astutely notes, “The diversity of the excuses is suspicious. When three separate vindications are offered for something there’s usually a fourth explanation … But there’s an underlying convergence to all the explanations: they were all reasons to eject Catholics and rotten Prods.”11

He makes an important point when stressing that the 1920 expulsions differed from previous episodes in that this time, they were more explicitly anti-socialist and there was a high degree of collusion by the Unionist Party leadership.

In the first week alone, during which the expulsions spread from the shipyards to other significant industrial enterprises across Belfast, roughly 5,000 workers were expelled, Baird among them: “As a skilled worker, a Protestant, and a socialist politician who would end up embracing republicanism, Baird became emblematic of the peculiarities of Belfast in 1920.”12

The anti-socialist violence was not limited to workplaces – the Independent Labour Party hall in Langley Street off the Crumlin Road in north Belfast was burned.

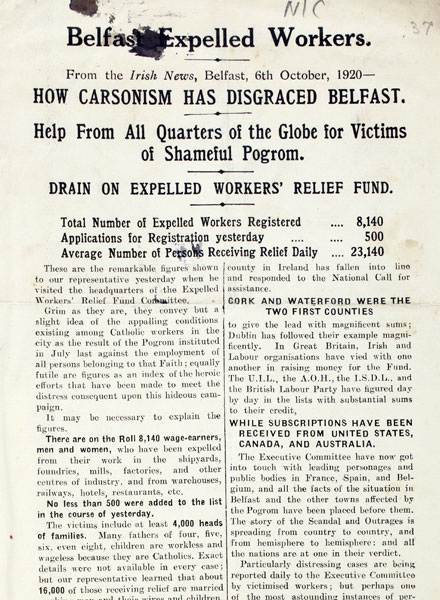

Poster issued by the Expelled Workers Relief Committee

Letter, signed by Baird among others, soliciting donations to the relief fund © National Library of Ireland ILB p300 p11

Baird became one of the leaders of an Expelled Workers Relief Committee which was set up in the aftermath of the expulsions. By October 1920, they estimated that 8,140 workers had registered for assistance from a relief fund which had been established – of those, a quarter were Protestants, there were 2,000 women, about 1,000 Catholic ex-servicemen and fewer than 1,400 skilled workers.

Turning for assistance to both the ITUC and the British TUC, delegations of the expelled workers received sympathetic hearings but little in the way of effective support. When Thomas Johnson, leader of the Irish Labour Party, addressed the conference of the British equivalent later that year, he didn’t mention Belfast.

1921: the year of disappointments

Under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, parliaments were to be set up for Northern and Southern Ireland, with the first elections for the new bodies scheduled for May 1921.

Baird, Harry Midgeley and John Hanna stood as socialists pledged to boycott the new Northern Ireland Parliament – their manifesto stated: “We are completely against partition. It is an unworkable stupidity … the interests of the workers of Ireland are politically and economically one.”13

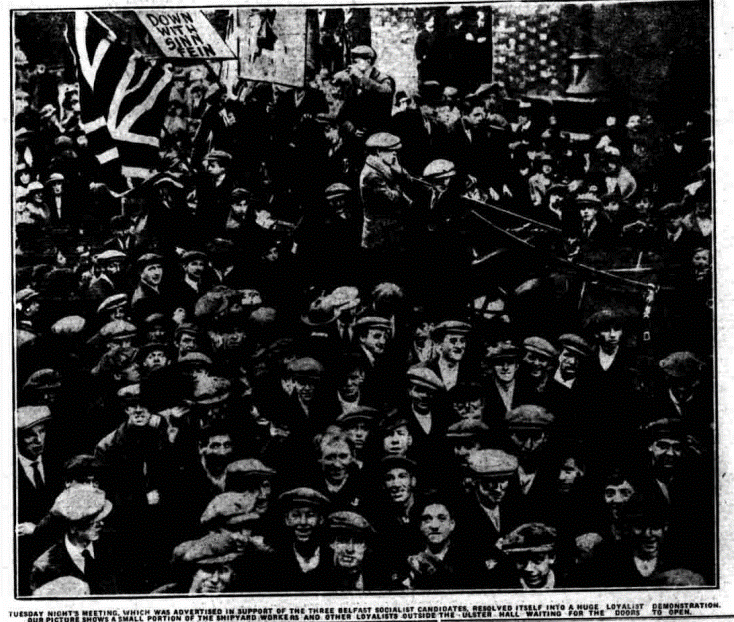

Baird and the others had booked the Ulster Hall for an election rally on 17th May but members of the British Empire Union and UESA organised a counter-demonstration: 4,000 shipyard workers marched to the hall, occupied it and hoisted four large Union Jacks on the stage. Arriving at the hall, the three socialists saw the lie of the land and decided to abandon their meeting.

Loyalist shipyard workers prevent a socialist election meeting from proceeding, 17th May 1921 (Belfast Telegraph)

Flushed with victory, the loyalist occupiers telegrammed James Craig: “Mass meeting of loyal shipyard workers who have captured Ulster Hall from Bolsheviks Baird, Midgeley and Hanna request that you address them for a few minutes.” A delighted Craig responded, “Well done, big and wee yards.” Further election meetings planned by the three were cancelled and printers declined to undertake work for them.14

Thus denied the opportunity to campaign in the northern state’s first supposedly democratic election, the results were inevitable. Baird, standing in Belfast South (of which Ormeau Ward was a part), came bottom of the poll with 875 votes; Midgeley got 645 and Hanna a mere 367. All three lost their deposits.

In September, Baird and other expelled workers addressed the conference of the British TUC. He asked the delegates:

“If Belfast intends to form a little back shop in the interests of exploiting employers I trust you will put a barbed-wire fence around it, and refuse to allow them any coal or steel or anything they require; and this will have a far-reaching effect. It will go a long way, no doubt, to settle the problem at Belfast, and will be a big influence in settling what you call the Irish question.”15

But Baird’s appeal for solidarity fell on deaf ears – the TUC’s component unions were more interested in maintaining their membership numbers, even if those included the people responsible for the expulsions. The only tangible effect of Baird’s speech was apoplexy on the part of the unionist press in Belfast – their treatment of him swiftly moved from ridicule to venomous hatred.

At around the same time, Baird, who had become Belfast branch secretary of the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union, led the entire branch to affiliate to the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) in Dublin. He had begun to develop contacts with the ITGWU by writing for their Voice of Labour paper and it was those contacts that provided the springboard for the next phase of his activism.

Waterford

On 9th May 1922, Baird attended his last meeting of Belfast Corporation. Less than two weeks later, he and 110 workers stormed a meeting of the Rural District Council in Thomastown, County Kilkenny, demanding that all roads in the area be maintained by direct council labour. Baird was now a full-time organiser for the ITGWU in the south-east and employers in the area now had a militant socialist from Belfast to contend with.

However, Baird himself also had new realities to contend with: the workers he was representing in the south-east were a very far proposition from the monolithic specialised trades in the huge industrial conglomerates of Belfast. Now, his members included farm labourers, dockers, flour millers and workers in creameries, bakeries and gasworks.

But as O’Connor highlights, “Baird’s biggest problem was reconciling rank and file militancy with the union’s increasingly cautious strategy.”16

This came to a head in the course of Baird’s biggest single battle during his time in Waterford – the farm strike of 1923: “Baird stood for the syndicalist militancy that had powered the Labour advance since 1917. Foran and O’Brien [senior figures in the ITGWU hierarchy] were pragmatists for whom the survival of the union was the priority.”17

In May 1923, the Waterford Farmers’ Association sought to impose a pay cut from 35 shillings to 25 shillings a week, as well as the abolition of the seasonal harvest bonus. A strike began in response on 17th May.

Just over a week later, Baird raised the stakes from those of a mere wage dispute – writing in the Voice of Labour, he stated that “farmers had no title to their land other than English Acts of Parliament.” But here, he was doing no more than re-iterating Labour Party policy, which advocated public ownership of the land.18

Initially, the strikers had the upper hand with flying pickets and sympathetic strike action coming close to breaking the farmers. But the Free State Army intervened in the form of 600 troops of the Special Infantry Corps who, by late June, had been deployed in Waterford to support the farmers.

Under military protection, farmers unload supplies from the SS Cargan in Dungarvan during the 1923 farm strike © Waterford County Museum

A curfew was imposed and martial law declared in the most-affected east of the county. Emboldened by the military support, farmers and other employers began bringing in scab labour and dismissing workers who refused to handle “tainted” goods. The dispute had now moved beyond farm wages to all-out class war.

O’Connor describes the farmers resorting to “White Guardism” in response to incidents of sabotage and arson. The latter was – at least in part – encouraged by Baird who, at one strike meeting, produced a box of matches and declared “Ye have these.”19

In response, government minister Kevin O’Higgins ordered the arrest of Baird in early September for suspicion of conduct likely to cause arson. He was interned in Kilkenny Gaol under military custody but began a hunger strike in October, whereupon Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy ordered his release. O’Higgns was not impressed, writing to Mulcahy and denouncing Baird as “an agitator of the most extreme type.”20

The strike dragged on until December, when it collapsed due to the tensions between Baird and the strikers on the ground versus the ITGWU’s head office in Dublin. Strike pay to its Waterford members had accounted for a quarter of the union’s total expenditure during 1923, even though they only made up 5% of the national membership – Foran and O’Brien said they couldn’t go on providing the strike pay and so the strike ended on 15th December.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given this latest defeat, Baird emigrated to Australia in 1927 and died there in 1948.

Conclusions

In an epilogue, O’Connor acknowledges the plot holes mentioned above, saying, “There are unfortunate gaps in our knowledge of Baird’s biography,” specifically referencing the unresolved questions about why his political ideas evolved as they did.

It is impossible to argue with O’Connor’s closing assessment:

“… he was typical of contemporary Belfast Labour activists in being a Protestant, in moving to the left after 1917, in being victimised, and in concluding that Labour depended on working class unity, that partition was inimical to unity, and that Unionism was an inherently reactionary force, fomenting sectarianism to smash socialism.”21

Baird’s commitment to the working-class cause led to him being subjected to violence in the north and internment in the south. His repeated requests for support and solidarity from the leadership of the trade union movement, in Belfast, Dublin and Britain, were all rebuffed. A series of defeats ultimately led to exile, then to obscurity.

But now, O’Connor has provided a brilliant study of a key leader of one of the most important, yet under-remembered, groups of the whole Decade of Centenaries and in this absorbing, richly-detailed account, he has restored to Baird the prominence that his struggles richly deserve.

This post is dedicated to the memory of the late Dr Éamon Phoenix, whose knowledge of Irish history was so encyclopaedic that he probably knew exactly what set James Baird on the path to socialism, who had the conversation with him and what day of the week it happened on. RIP.

References

1. Emmet O’Connor, Rotten Prod: The Unlikely Career of Dongaree Baird (Dublin, UCD Press, 2022), p11.

2. Ibid., p17.

3. Ibid., p17; Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants – The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920-27 (London, Pluto Press, 1983), pp13-14.

4. O’Connor, Rotten Prod, p17.

5. Ibid., p1.

6. Ibid., p23.

7. Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p236.

8. O’Connor, Rotten Prod, p36.

9. Ibid., p43.

10. Belfast News-Letter, 13th July 1920.

11. O’Connor, Rotten Prod, p42.

12. Ibid., p43.

13. Ibid., p60.

14. Ibid., p62.

15. Ibid., p68.

16. Ibid., p77.

17. Ibid., p83.

18. Ibid., p87.

19. Ibid., p91.

20. Ibid., p77.

21. Ibid., p98.

Leave a comment