The IRA’s Northern Offensive, May 1922 – Part 3. The third in this series of blog posts examines how the plan drawn up in April 1922 was – and was not – carried out from May onwards.

Part 1 is available here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2022/12/28/we-have-set-up-a-military-council-for-the-north/

Part 2 is available here: https://thebelfastpogrom.com/2023/01/07/belfast-city-to-be-held-up-republican-troops-to-occupy-positions-in-sufficient-strength-to-hold-same/

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes.

The plan begins to unravel

The Northern Offensive was timed to begin on the night of 2nd/3rd May, but it was already plagued by confusion before that date. Cohesion between the various Northern Divisions, which was critical to the success of the plan, was lost before any of them even went into action – according to Séamus Woods, O/C of the 3rd Northern Division, instead of a co-ordinated attack, a piecemeal approach was adopted:

“As the Stuff at GHQ was not quickly available our last load for No. 2 (Antrim) Brigade was only passing through Belfast two days before the date appointed for general operations. The convoy broke down and as a result it would not reach the Brigade area till the day after operations were to commence. As want of Stuff would have hampered the Brigade entirely and as there was no possibility of getting Stuff in after the first night’s job, I went to GHQ to see if a postponement of three days could be arranged. The Chief of Staff agreed to this and arranged accordingly. No. 2 Division could not postpone their plans on such short notice and they carried on. The Chief of Staff instructed me not to move until he would have a meeting of the Northern Divisional Commandants. That meeting was held at GHQ on Friday 5th May and it was decided that each Division complete its plans and await instructions from GHQ. It was left to the Chief of Staff to determine a date, to be in the near future, on or after which every Division would strike.”1

This was not an auspicious start – but worse was to follow.

Countermanding orders

Although men under his command had fought the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or Specials) at Clady in Tyrone as recently as February, Joe Sweeney was adamant that, regardless of the plan that had been drawn up by the IRA Ulster Council of which he was a member, his 1st Northern Division would not participate in its execution: “Collins asked me what I thought of the prospect of fight in the north when I handed over the D.P. rifles. I said ‘It’s right to make those fellows fight.’ I wouldn’t take any part in it nor would I send in any men.”2

Joe Sweeney, O/C 1st Northern Division – refused to take part in the Northern Offensive

Speaking to Ernie O’Malley years later, he was keen to stress that while he didn’t want to participate in the plan, neither would he try to undermine it – in fact, he would have been willing to co-operate if only he had been asked:

“Aiken seemed to have the principal say about Northern matters for he took tenders of war flour, etc. out of the Bush [Beggar’s Bush barracks in Dublin] for the North. Aiken and Joe Doherty were in Burtonport looking for cars to go to Moville for a raid but they never got in touch with me. There was another man with them. I could have got them cars with IRA drivers.”3

He also claimed to O’Malley, “I had no use for the north for I thought they were no good. I got no encouragement from Collins or from GHQ about helping the north nor had I any instructions.”4

On both of the latter points, he was dissembling: he definitely had got encouragement from GHQ – as noted in Part 2, the plan for the offensive outlined in Clones on 21st April required his Division “to take all posts in general sweep from Donegal concentrating on Derry.”5

In addition, he definitely did get instructions – but not ones that anybody was expecting. A Derry IRA officer named Daniel Kelly had been instructed by Sweeney to occupy a coastguard station in Buncrana, county Donegal, for use as a barracks – Kelly recalled:

“Previous to us taking over this barracks we had plans to start the fight against the Specials in Derry … There was a general uprising in the plans for the North some time in May, 1922. All preparations for this rising had been made all over the Six-County area when instructions came to us to have it called off. A man named Sherry was sent on a motor bike to the various centres with orders calling off the Rising. A few areas through some mistake did not get word in time.”6

Sweeney was not the only divisional commander to receive a countermanding order telling him not to participate in the offensive. Frank Aiken, the chair of the IRA’s Ulster Council, was still taking orders from Chief of Staff Eoin O’Duffy in GHQ, while endeavouring to keep his 4th Northern Division neutral on the question of the IRA split; Patrick Casey, the Newry Brigade Vice O/C who had previously marvelled at the quantities of weapons moving through Dundalk, remembered:

“I returned to Dundalk that evening [18th May] as directed and I saw Frank Aiken. I asked him what was the position and he replied that our Division was taking no part in the rising, but that there was no cancellation so far as the remainder of the northern counties was concerned. He gave as his reason the fact that the Armagh Brigade was not fully equipped and for that reason he felt justified in withdrawing his Division from action. I pointed out that the South Down Brigade was fully armed and that we should be permitted to take our part. He was, however, adamant and his orders were paramount.”7

Aiken’s divisional Adjutant, John McCoy, knew that there was more to this than a mere question of logistics:

“At the last moment the rising on 19th May was cancelled. Orders to the effect came to us with only sufficient time to enable the operations to be called off. In some other areas, notably Tyrone, Derry and Belfast, Co. Antrim and East Down the cancellation did not reach the men in time and the operations commenced. I am not in a position to define exactly how this muddle of the orders cancelling the rising occurred. I believe that in the case of the 3rd Northern Division the fault lay with the pro-Treaty headquarters in not providing alternative means of notification which would ensure the order arriving by at least one route.”8

McCoy would later act as one of the lead interviewers for the Bureau of Military History, with particular responsibility for gathering the statements of northern veterans. One of those he spoke to was Tom Fitzpatrick, O/C of 3rd Northern’s Antrim Brigade, who told McCoy: “The operation was countermanded but the orders did not reach our Division before we actually started fighting.”9

John McCoy, Adjutant, 4th Northern Division – knew about the countermanding orders

A critical issue is whether those orders were even sent to 3rd Northern – after all, Aiken told Casey that “there was no cancellation so far as the remainder of the northern counties was concerned.” While the Bureau of Military History statements do not include the interviewers’ questions, one hypothesis is that McCoy, knowing that Aiken had received a countermanding order, subsequently asked Fitzpatrick something on the lines of “Why did you not abide by the countermanding order?” to which Fitzpatrick replied, “We didn’t get it.” We will return to this issue.

The existence of the countermanding orders was certainly known about within a few months, even outside IRA circles. A Tyrone barrister, Kevin O’Shiel, had been appointed Director of the Provisional Government’s North East Boundary Bureau in the spring of 1922 – he was thus one of Michael Collins’ key advisors in relation to the north; writing to the government in October 1922, he stated:

“There was no cut or dry policy and whilst I was urging a policy of peaceful do-nothingness in Northern Committees, the two branches of the IRA were actively making united preparations to invade the North East in alliance and were only called off at the last moment because of some man’s intervention.”10

The offensive begins – Derry and Tyrone

The 2nd Northern Division began its attacks on the night of 2nd/3rd May when it attacked the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks at Bellaghy and Draperstown in county Derry – one RIC officer was killed at Bellaghy, but neither barracks was captured.11

The following night, Seán Lehane, whose anti-Treaty 1st & 2nd Northern Division had received no countermanding order, sent men to attack two posts across the border. Charlie Daly led one column of sixteen men to attack a Specials barracks in Molenan House two miles southwest of Derry city, while Lehane himself led another column of thirty men to attack what he thought was a British military camp on the road from Buncrana to Derry.12

Although Lehane and his men believed they were attacking a military post, it was actually a police border checkpoint and the attack was easily repelled, as an RIC report laconically noted: “On the morning of the 4th inst. a determined attack was made by IRA from Donegal on No. 2 Control Post on Buncrana Road, which is near the Border. The attackers were beaten off.”13

Molenan House today

Daly’s column had no more luck at Molenan House, where the Specials closed the steel shutters and barricaded themselves in, so Daly and his men had to retire back across the border.

The same night, 2nd Northern was back in action again – in county Derry, an RIC officer was killed in an ambush at Moneymore, while a three-man patrol of Specials was wiped out in an ambush at Ballyronan. The latter attack re-ignited the cycle of vicious reprisals which had been prevalent during the fighting along the border earlier in the spring – two local Catholics were killed by Specials on 6th May and a further three on 11th May.14

Meanwhile in Tyrone, also on 3rd May, an ineffective attack was mounted on Coalisland Barracks. Here, as the IRA retreated, they set fire to the house of a member of the Specials and then killed a colleague of his who attempted to tackle the blaze. Two Catholics were killed by Specials in retaliation and their bodies mutilated. An attack on Dunamore Barracks in Tyrone the same night sparked a similar reaction – one RIC officer was killed and Specials killed a Catholic in response.15

RIC Crossley tender outside Coalisland Barracks

Violence by the Specials reached a new peak on 19th May – after 2nd Northern burned a flax mill in Desertmartin in county Derry, four Catholics were killed in reprisals.16

Stung by the ferocity of the Specials’ response, civilians began sleeping in their fields rather than their homes while the IRA started to flee across the border into Donegal. Meanwhile, Lehane could accomplish little from inside that county – one of his Brigade O/Cs, Cork man Mossy Donegan, later admitted:

“The activities carried on near and over the Border were principally of a nuisance value. The number of men available to our people was small – I should say 10 to 20 men who were not capable of any serious large scale attack on enemy posts for the purpose of capture. Hit and away activities at posts on or inside the border, destruction of block houses, upsetting communications, such are the types of activities carried on.

From the purely military point of view, I doubt if these activities seriously worried the northern forces – British military, RUC and Special Constabulary – very much.”17

All that had been accomplished so far was that the Unionist government now knew that the IRA had embarked on a fresh campaign but also that, as evidenced by the numerous barracks attacks and ambushes in such a short space of time, this was a much more concentrated and co-ordinated effort than had been the case with the more sporadic episodes near the border from February to April.

The 3rd Northern Division joins the offensive

Woods and 3rd Northern had sought and been granted a second delay to the start of the offensive, this time from 5th to 19th May, as they had devised a plan to break into the RIC headquarters in Belfast at Musgrave St Barracks and capture four Whippet armoured cars and eight Lancia “cage cars,” as well as rifles.

Musgrave St Barracks; an RIC Whippet armoured car in Clifton St, Belfast

On the night of 17th/18th May, a friendly policeman admitted a party of twenty-one IRA men to the barracks, including Woods and Belfast Brigade O/C Roger McCorley. They were about to start the armoured cars and were tying the rifles into bundles for transporting when a struggle broke out in the guard room in which a police sergeant was shot and killed. This raised the alarm and a sentry began firing on the IRA with a machine-gun. The IRA were forced to flee empty-handed.18

Later in the month, an attempt was made to infiltrate a Specials outpost in Dock St, while sniping attacks were launched on Smithfield, Springfield Road and Cullingtree Road Barracks, but these attacks were all driven off. A policeman was killed in the Cullingtree Road attack and several Specials killed in local attacks elsewhere in Belfast but the Northern Offensive in the city was turning out to be just as much of a damp squib as it had already proved to be in Derry and Tyrone.

Cullingtree Road Barracks after the attack – broken windowpanes are visible on the upper floors

The Antrim Brigade also began operations on 19th May – RIC barracks at Ballycastle and Cushendun were attacked but neither was captured; Martinstown Barracks near Ballymena was also attacked, with one Special being killed, but when police reinforcements arrived from Ballymena, the IRA were forced to withdraw. Elsewhere, the Belfast-Derry railway line was destroyed and Antrim Castle was burned – this attack on the British landed gentry wasn’t completely heartless as “they carried out Lady Masserene, who was pretty old, and had her wrapped in rugs on the lawn, while the Castle was being destroyed.”19

Antrim Castle, burned by the IRA on 19th May

On 24th May, having blown up a bridge, a group of three IRA men was surrounded after attacking a Specials convoy at Glenariffe in the Glens of Antrim; although one of the men succeeded in escaping, the other two were clubbed to death after running out of ammunition. The following month, a mixed convoy of British troops and Specials entered the village of Cushendall on 24th June and killed three Catholic men, among them two off-duty members of the IRA. The Cushendall killings were the subject of two official enquiries: the first, carried out by a British civil servant, found that there had been no shooting in the village by anyone except the British military and Specials; this was not published and was instead followed by a second investigation, this time by the RUC Deputy Inspector-General, which unsurprisingly exonerated the Crown forces.20

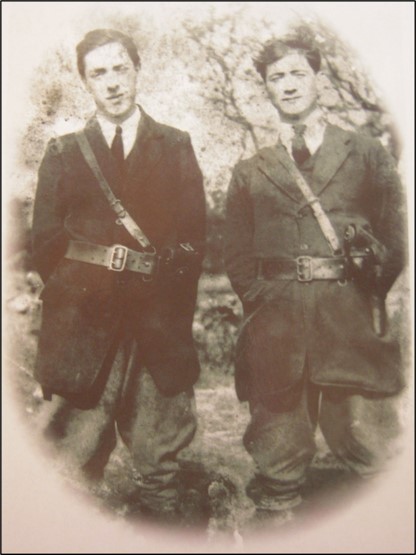

Charles McAllister and Patrick McVeigh, Antrim Brigade, IRA, killed at Glenariffe on 24th May

The fire-bugs

A scorched-earth strategy had been discussed enthusiastically at the inaugural meeting of the Provisional Government’s North East Ulster Advisory Committee in mid-April so the Belfast Brigade’s contribution to the Northern Offensive also involved an element of economic warfare directed at unionist-owned businesses in the city centre, in the form of an arson campaign.21

In reality, this was the revival of a plan that had been drawn up at the end of 1920 on Collins’ orders after the burning of Cork city centre by the Auxiliaries – he had wanted central Belfast to be burnt in retaliation. The plan was called off at the last minute – depending on which IRA veteran you believe, either at the behest of the Catholic Bishop of Down and Connor who appealed to Collins, or because a Volunteer blurted out the details to a priest during confession and the priest then informed the authorities.22

Doran & Co. distillery & warehouse, Donegall Quay, burned by the IRA on 19th May

Within forty-eight hours of its abortive raid on Musgrave St Barracks, the IRA set fire to a dozen businesses on 19th May, the largest of which was Doran & Co., a distillery and bonded warehouse on Donegall Quay. Thirty-six more businesses were targeted between then and the end of the month.23

During June, arson attacks were the only offensive operations that the Belfast IRA could mount and a total of eighty-six businesses were attacked during that month.24

But by then, the Belfast arson campaign represented the last sting of a dying wasp. In Antrim, the Brigade O/C Tom Fitzpatrick was wounded in a skirmish with military and police in late May and brought to a nursing home in Belfast to recuperate; days later, he was joined in the very same ward by Roger McCorley, O/C of the Belfast Brigade, who was wounded on 31st May.25

Roger McCorley, O/C Belfast Brigade and Tom Fitzpatrick, O/C Antrim Brigade – both were wounded and out of action by the end of May

Belleek-Pettigo

At the end of May, despite the countermanding order he had received, some of Sweeney’s Free State Army troops did, after all, become involved in conflict with Specials and British military. On 27th May, a force of Specials crossed Lough Erne by boat, landed near Belleek on the Donegal-Fermanagh border and began sniping at anyone on the southern side seen to be carrying arms. Having come under attack in response, they withdrew to an island in the lake where they were reinforced by another hundred Specials. On learning of this, anti-Treaty 2nd Northern men who had taken refuge in nearby Pettigo dug trenches to prevent the Specials sending more reinforcements by road from Enniskillen.26

The next day, Sweeney went to Pettigo to investigate for himself:

“The Orangemen were very active in Belleek Pettigo. We had men on the other side in the first fort. I went down there in a car one day. On a hill near the fort I heard shooting. I saw an open Lancia car coming from the Belleek direction and when it was near, the first fire was opened on it. The driver was killed, the other man jumped out and ran towards Belleek, I could see the bullets cutting the dust around his heels. The car had gone across into our territory … I told our men to raid houses across the border that night.”27

Specials’ Lancia armoured car, captured in Pettigo

Over the next two days, further attempts by Specials to break through into Pettigo were repelled and a standoff ensued. By now, Sweeney’s men were fighting alongside those from 2nd Northern – Lehane reported, “The Deputy O/C [Daly] thought this perhaps, might, afford an opportunity where Republican and Free State forces could combine and fight against the common enemy and so avoid civil war in Donegal at least.”28

The British military commander in the area was instructed to take both Pettigo and Belleek, so on 1st June, a number of battalions of British troops – from the Lincolnshires, Manchesters, Staffordshires and Scottish Borderers – accompanied by a detachment of artillery moved into position outside Pettigo. Over the course of the next two days, three combined attacks by British military and Specials were driven off by the joint efforts of the Free State and anti-Treaty troops.

But on the morning of 4th June, having given the Free State commander a fifteen-minute ultimatum to evacuate, the British began shelling the village, forcing both Free State and 2nd Northern forces to withdraw; it was the first time the British had used artillery in Ireland since the Easter Rising of 1916. British columns, accompanied by armoured cars, then fought their way into the village. Seven defenders were killed by either artillery or rifle fire; three were killed on nearby Drumhariff Hill, where their machine-gun post held out until all ammunition was exhausted, thus ensuring that the British were unable to fully encircle Pettigo and the remaining defenders were able to retreat.

Four days later, British troops and armoured cars successfully captured Belleek.

British troops in Belleek, having captured the village

In light of the events at Pettigo, it was no surprise that at a meeting of the Provisional Government on 3rd June, “It was decided that a policy of peaceful obstruction should be adopted towards the Belfast Government, and that no troops from the twenty-six counties either those under official control or attached to the Executive should be permitted to invade the Six County area.”29

This decision reiterated the practical effect of the countermanding orders previously issued but raised an interesting possibility regarding “Executive” forces: to what lengths would Sweeney’s pro-Treaty 1st Northern go to prevent Lehane’s anti-Treaty 1st & 2nd Northern from launching fresh attacks over the border? Would pro-Treaty forces go so far as to physically protect the Unionist government in the north?

Woods appeals for help

In a later report to GHQ, 3rd Northern’s Woods attempted to put a positive glass on what had been a lacklustre campaign:

“Each Brigade made a good start and the men were in great spirits anxious to go ahead, but in a few days the enemy forces began to pour into our area as no other Division was making a move. Things became so bad in No. 3 (East Down) Brigade where lorry loads of Specials were coming in from Newry (4th Northern Divisional area) that on 24th May the Divisional V/C went and saw the Chief of Staff. The Chief of Staff said he would order out the 4th Northern Division immediately; we kept the men in No. 3 under arms in the hope of the enemy having to bring back their Specials to Newry.

A week later, as nothing was happening in other areas, we found it necessary to disband the columns and leave the men in groups of three or more to move about as best they could, in the hope of re-mobilising them when operations became general.”30

The Divisional Vice O/C at the time was Roger McCorley. What is hugely significant about his visit of 24th May to O’Duffy is that he was not berated for 3rd Northern having failed to follow the countermanding order. Nor was he told that 4th Northern weren’t “making a move” because they had been told not to – instead, O’Duffy promised to order them into action. But unlike the countermanding order, Aiken received no such order. There would be no relieving column coming up the Lagan valley to Belfast.

References

1 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 27th July 1922, Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archives Department (UCDAD), P7/B/77.

2 Joe Sweeney interview, Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/97.

3 Ibid.

4 Joe Sweeney and Peadar O’Donnell interview, O’Malley Notebooks, UCDAD, P17b/98.

5 Pádraig Quinn Collection, Kilmainham Gaol Museum, 20MS-1P41-08.

6 Daniel Kelly statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives, WS1004.

7 Patrick J. Casey statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS1148.

8 John McCoy statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0492.

9 Thomas Fitzpatrick statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0395.

10 Assistant Legal Advisor (Kevin O’Shiel) to each Minister, 6th October 1922, Hugh Kennedy Papers, UCDAD, P4/388.

11 Adrian Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2018), p134.

12 Michael O’Donoghue statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS1741 Part 2.

13 RIC Divisional Commissioner’s bi-monthly report, 16th May 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/152.

14 Grant, Derry, p135-136.

15 Fergal McCluskey, Tyrone: The Irish Revolution 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2014), p122.

16 Grant, Derry, p136.

17 Mossy Donegan to Florence O’Donoghue, 15th September 1950, Florence O’Donoghue papers, National Library of Ireland, Ms 31,423 (6).

18 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 19th May 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/a/173.

19 Tom Fitzpatrick statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0395.

20 Charles McAllister, MSPC, Military Archives, DP6008 & Patrick McVeigh, MSPC, Military Archives, 2D488; for the Cushendall killings, see Cushendall Inquiry, PRONI, HA/20/A/2 (series) and Christopher Magill, Political Conflict in East Ulster, 1920-22 (Woodridge, Boydell Press, 2020), p100-112.

21 Minutes of meeting of North East Ulster Advisory Committee, 11th April 1922, National Archives of Ireland (NAI), D/Taoiseach S1011.

22 Joseph Murray statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0412; Joseph Billings, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34REF07576.

23 Belfast News-Letter, 20th, 22nd & 23rd May 1922; Northern Whig, 24th–26th & 30th May 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 27th May 1922.

24 Operations carried out by No. 1 Brigade during June, in Adjutant 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 7th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

25 Thomas Fitzpatrick statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0395.

26 Nicholas Smyth statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0721.

27 Talk with Joe Sweeney, 28th January 1964, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/D/43.

28 Seán Lehane to GHQ, 19th September 1922, Ernie O’Malley Papers, UCDAD, P17a/63. More extensive accounts of the Battle of Belleek-Pettigo can be read at https://ansionnachfionn.com/2015/06/08/the-battle-of-pettigo-and-belleek-may-to-june-1922/ and https://erinascendantwordpress.wordpress.com/2022/05/21/sparks-among-the-embers-the-battle-of-belleek-and-pettigo-may-june-1922/#_ftnref16

29 Provisional Government Minutes, 3rd June 1922, National Archives of Ireland, G1/2 https://www.difp.ie/volume-1/1922/northern-ireland/296/#section-documentpage

30 O/C 3rd Northern Division to Chief of Staff, 27th July 1922, Mulcahy Papers, UCDAD, P7/B/77.

Leave a comment